This Little-known Reserve Is Home to More Than 10% of the Rhinos in Kenya — Here's What It's Like to Visit

Three years ago, there were no southern white rhinos in Kenya's Lewa-Borana Landscape. Now, there are 123 — and 141 critically endangered black rhinos.

Backdrop Production

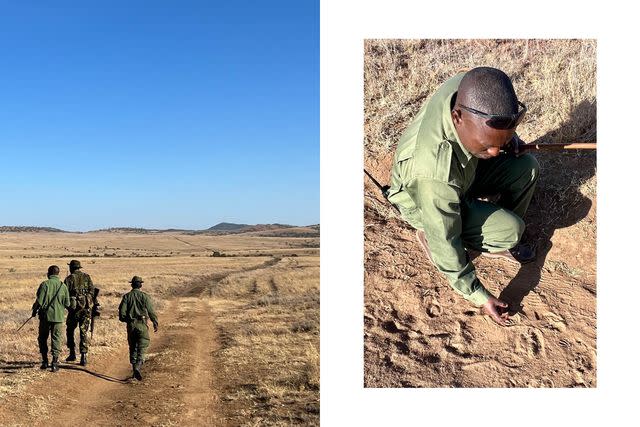

It’s early morning in the Borana Conservancy, a wildlife reserve in central Kenya’s Laikipia Highlands. Nissa Kinyaga, the guide at the wheel of my safari vehicle, brings us to a halt at the bottom of a grass-covered slope where a group of rangers in army fatigues is waiting, Mount Kenya silhouetted on the horizon behind them. These three men are part of Borana’s rhino-tracking program and the lodge I’m staying at, Lengishu, has arranged for me to join them on their morning patrol.

But first, a word about rhinos. Three years ago, there were no southern white rhinos in this 32,000-acre reserve; today, there are more than 123 living between Borana and the adjacent Lewa Wildlife Conservancy, together with around 141 of the critically endangered black rhino. The Lewa-Borana Landscape, as the two reserves are collectively known, is now home to more than 13 percent of Kenya’s rhino population — a fact that’s in large part thanks to the efforts of the three men standing in front of me, and others like them.

Backdrop Production

As I step out of the vehicle, Richard Karmushu, the group’s lead tracker, lifts his binoculars to his eyes and cries, “There, black rhino!” Following his gaze I see a female — Karmushu tells me she’s known as Linda — trotting at a surprising clip across the bush some 200 yards away, her two-year-old calf keeping pace at her side. “Rhinos have a very good sense of smell,” Karmushu says with a smile. “She caught wind of us and is running away.” Just as well, he adds: black rhinos can be aggressive, meaning humans should always keep a safe distance.

Backdrop Production

I sneak a sideways glance at the rifle hanging from the shoulder of the group’s six-foot-something anti-poaching guard, and we set off into the bush on foot. After a minute or two, Karmushu stops at what looks like a mound of earth some three feet high. This, he explains, is a midden, or dung heap — a territorial marker used by both black and white rhinos. Pulling apart the dried dung balls, he points out the difference between those of the black rhino (lighter and more fibrous, reflecting a browser’s diet of shrubs and trees), and the white (darker, reflecting a grazer’s diet of mostly grass). “White rhinos came to Borana from the neighboring reserves because we have a lot of open areas to graze on, and a lot of grass,” he explains.

Flora Stubbs/Travel + Leisure

We walk on, spotting rhino tracks in the dust as we go. Karmushu explains how a system of ear-notching helps trackers monitor the health and whereabouts of the rhinos living on the reserve. Though the work can be dangerous (face-offs with poachers are rare these days, but not unheard of) the vast majority of the unit’s time is spent observing the creatures, their habitat — and their dung — from afar.

Flora Stubbs/Travel + Leisure

Brian Siambi

I’m fascinated by Karmushu’s stories of his work on the reserve, but after an hour or so of walking, I’m also starting to get hungry. A few minutes later, the tracker points to a grassy spot in the shade of a huge candelabra tree, where a team of chefs and servers from Lengishu lodge are preparing an elaborate bush breakfast at a table set with forest-green linens and brass tableware. Rarely have eggs Florentine and a cup of hot coffee been so welcome.

The morning’s mix of adventure and personalized luxury was typical of my stay at Lengishu, a lodge on the Borana Conservancy opened in 2019 by a British couple named Joe and Minnie MacHale. After breakfast I headed back up to the lodge, which consists of low-slung buildings with traditional "makuti" thatched roofs, perched on a hill looking east over one of Borana’s spectacular, sweeping valleys. (On the far horizon lies the double-humped mountain the lodge was named after, which means “where the cattle graze” in Masai.) The place sleeps 12 and has a high-ceilinged living space with fireplaces, deep sofas, and a grand dining table, making it perfect for big groups of friends or relatives.

Backdrop Production

Minnie MacHale gives me a tour of the property, which she personally decorated in a style that — much like her — exudes equal parts warmth and glamor. Pointing to a studded wooden chest in the entranceway, she says, “My parents bought that from a trip to Zanizbar, it was my dressing up box as a child growing up in Scotland.” The rugs in the bedrooms? They were made by a women’s collective from the nearby Meru community.

“Feel free to pop your head around any door, just have a poke around,” she adds, briefly disappearing into a closet. “We have straw hats you can borrow down by the pool, and down jackets if it gets chilly in the evenings. They’re only Uniqlo, but they do the job!”

By now the dry heat of the highlands is beginning to beat down, so I head for a swim in the pool — stopping to borrow one of Minnie’s stylish, wide-brimmed straw hats along the way. Weaver birds have built a colony of spherical nests in the acacia trees over the pool; resting on its infinity edge between laps, I spot a family of elephants trooping down to a drinking hole some 300 feet in the valley below.

Brian Siambi

Sufficiently cooled, I join Joe MacHale for a poolside glass of Tusker beer, where he tells me how Lengishu came about. “We built this first and foremost as a family home,” he explains — one that could accommodate the couple’s four adult children and rapidly expanding brood of grandkids. “Minnie spent time in Kenya in her 20s and had always wanted to return.” So it seemed like a sign when, decades later, the couple’s eldest son, who had worked as a photographer in Kenya, heard about a plot of land going up for sale in Borana.

Brian Siambi

The MacHales are one of nine shareholders in the Borana Conservancy, meaning they underwrite the costs of its operations and conservation efforts — including the anti-poaching program — as well as an impressive wildlife education program, a mobile clinic, a water safety program, and a program to help improve the health of local cattle.

Their efforts are clearly paying off. On a game drive that afternoon, the reserve teems with wildlife. My guide and I spot two lionesses basking in the grass; more rhinos‚ this time white, asleep under a tree; a herd of the endangered Grevy’s zebra; countless elephants and giraffes; and, perhaps most thrillingly, a pack of hyena cubs, which emerge from their burrow one by one and proceed to gambol around, rolling and play-fighting as the dust around them is kicked up into the air and suspended in beams of evening sunlight. From helping protect some of Africa’s most mighty creatures that morning to observing these tiny, fragile animals at sundown, it felt as if Borana — and, more specifically, Lengishu — had delivered everything I could have hoped for from a safari, in the space of just one day.

How to Book

Scott Dunn: This luxury tour operator can arrange stays at Lengishu, which include food and beverage along with a wide range of activities, including rhino tracking and fly-fishing on Mount Kenya. Scott Dunn can also arrange one-night stopover stays with Hemingways Collection properties in Nairobi. Tours start at $11,950 per person for five nights, including round-trip business-class flights and private transfers.

How to Get There

East African Air Charters: Operates private, direct flights to Borana Conservancy, with an airstrip just a 15-minutes drive from Lengishu.

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.