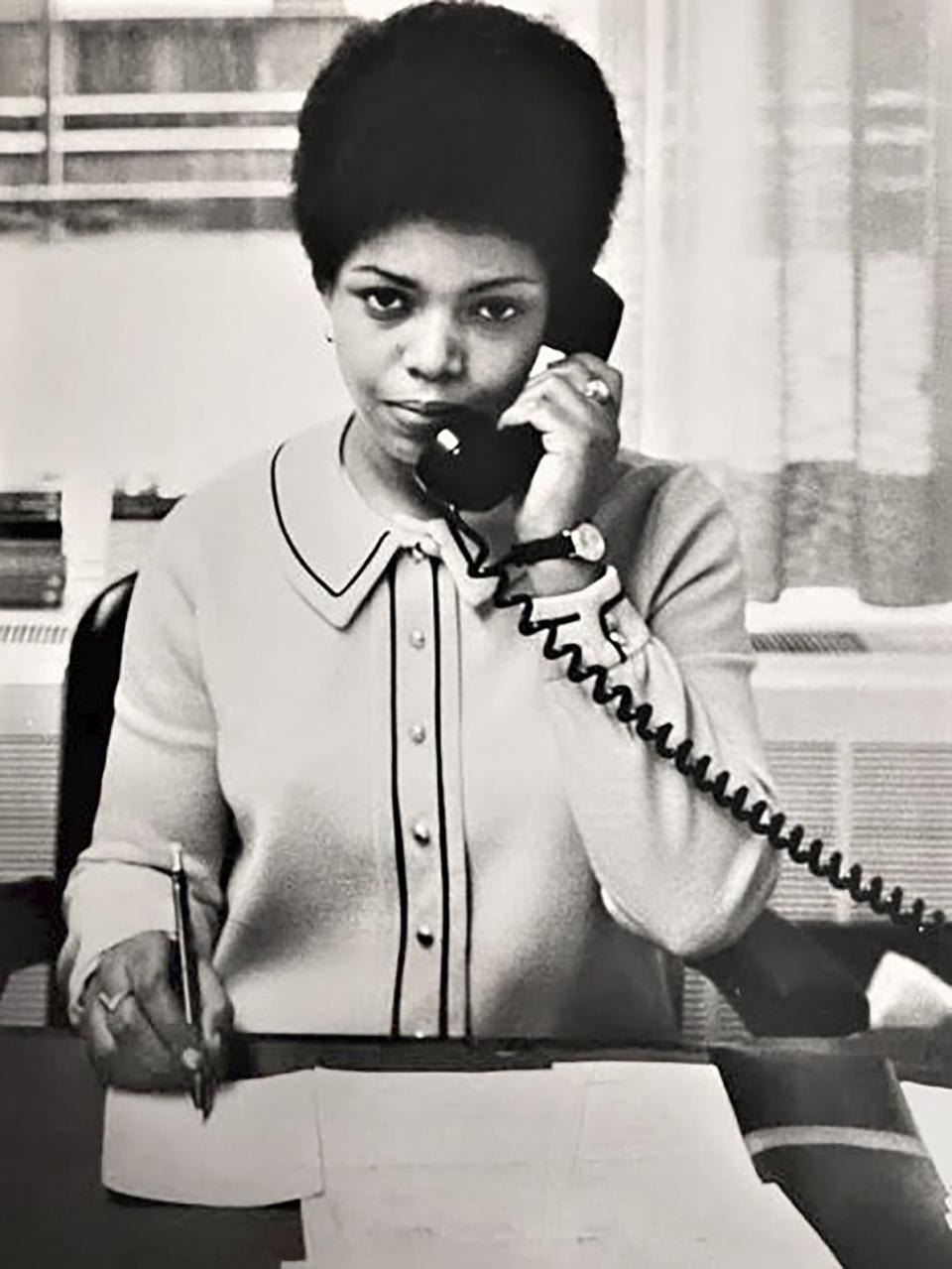

Literary Agent Marie Brown Re-Wrote Publishing Culture

“Hearst Magazines and Verizon Media may earn commission or revenue on some items through the links below.”

Interview by Sara Bey/

Photograph by Flo Ngala

Sara Bey: Why don’t we start by just talking a little about yourself, where you’re from, where you went to school, things like that.

Marie Brown: Now, you know how old I am. This could go on for two hours. I was born in Philadelphia, and left there at a very early age, as an infant, because of my father’s work. He was teaching at Hampton, now university. It was Hampton Institute then, and he taught there for about eight or nine years and then accepted another teaching position and dean of the school of engineering at Tennessee State, in Nashville. So, I spent probably the first 16 years of my life in the South at Hampton, Virginia, and then in Nashville, Tennessee. Subsequently, Daddy moved back to Philadelphia, which was his hometown as well as my mom’s, and he accepted a job in Philly. So, I then transferred—in the middle of high school, which was traumatic—to go to school in Philadelphia, to finish high school in Philadelphia. What was interesting about that was that I had only attended segregated schools in the South, and when I went to register for high school in the second half of the 11th grade, this was the first time that I had attended an integrated school.

SB: How did it feel to attend an integrated school?

MB: I was sort of stunned at the difference. I could sense the difference in the classrooms because, at the time, Germantown was predominantly white, and there was one Black—African American, whatever we were then—teacher, Mrs. Wright. She taught math, and it was my understanding that she was the toughest math teacher, and I was blessed not to have her because that’s my worst subject. So that was different, because I had some of the finest teachers that anyone could ever have, anywhere, at my high school in the South, and they were all Black. And they really tolerated nothing, no nonsense. It was like, “I know your mother and your father, and I know where you live,” and this was it.

So here I was in this environment without friends, and I was the new girl in the middle of this student body who had grown up together. So that was challenging. The other thing that was challenging was that my English teacher and my French teacher really, really gave me a hard time, and my mother had to make several visits to the school, because the English teacher, first of all, accused me of cheating because it was just impossible that a Black girl from the South could even know these things. Mind you, my mother was an English teacher. The French teacher, she refused to believe that I could speak the language and translate the way that I did, but she had no idea how my French teacher in Nashville, Madame Williams, she tolerated no English in her class, and we were expected to excel. So, my new teacher would say things like, Well, you must be Haitian, because you speak French.

SB: How did you get into publishing?

MB: I was mid-20s, working as a coordinator in the office of integration and intergroup education, responsible for programming in one of Philadelphia's eight school districts. That’s when I met a woman, Loretta Barrett, from Doubleday. She came to one of our in-service training sessions to talk about the new multicultural books that were being published, motivated by civil rights advocacy and Black history. As it turned out, she had taught with my mom in Philadelphia, and she discovered that I was Mrs. Dutton’s daughter and invited me, whenever I was in New York, to have lunch. So, that’s what I did. My best friend and I went off to New York, and I called Loretta for lunch, and she said sure. It was a very publishing-type experience, very fancy, in a French restaurant, something I had never experienced in life, ever.

She suggested that I speak to some people at Doubleday about what I was doing in the school system with multicultural books because she was editor of a new series of multicultural books, Zenith Books, and Zenith Books had been conceived and launched by a Black editor, possibly the first Black editor in trade book publishing, Charles Harris. I said, sure, I’ll talk to the powers that be or anybody else interested in knowing what I’m doing in Philadelphia. They set up a number of meetings so that I could discuss my job in Philadelphia and which books were the most popular in the curriculum, and so on. And as it turned out, it was a job interview. I don’t even know if they knew it when I walked in the door, but given the fact that this was the era of affirmative action, and they were not finding too many Black folks hanging around and wanting to pursue careers in publishing, here I was, all the way live. And they said, Oh, would you like to have a job?

So I went back to Philly, and I thought about it, and I said, Well, I can always return to the school system. I don’t know when this opportunity will occur again, and I love books—and mind you, Sara, I knew nothing about the publishing industry, just like most people don’t. Because we just don’t have the exposure. I didn’t know anybody except Loretta, who I just happened to meet by chance. So, anyway, I said OK.

SB: What were some hurdles that you had to jump through when you first began your publishing career?

MB: Well, it was sort of challenging to be considered the authority on everything Black, and that’s still the case. And I experienced blatant racism and as well as very subliminal racism, where, in professional spaces, the N-word was used, and it was like, Oh my God, this is something that you have to really figure out how you’re going to manage these circumstances, and I did. I had to determine how I was going to continue working in that environment and not lose my soul.

SB: That kind of leads also into my next question. Was there anything you noticed when you first began working in publishing that you didn't like and really wanted to change? Maybe along the lines of how maybe Black people were represented in books?

MB: Well, the fact is that we weren’t represented in books. There was a void. Otherwise, I would not have had that job. Representative Adam Clayton Powell was the one who really triggered the action by publishers to start looking for people like me to work in the industry. He had a hearing in the House of Representatives on diversifying book publishing, both in terms of career opportunities and the books themselves, publishing more books. You can’t even imagine anything like that happening today, but he was the chairman of the House Education Committee, and so he commanded the publishers to come to Washington to testify, just as you see in any of these other hearings, about, What are you all doing? Oh, so you’re not doing anything. But what now? What are you going to do about it?

And that’s when everybody had got on the bandwagon, in the ’60s up through the early ’70s, and produced many, many, many books, many multicultural books. A lot of them were not good, but many of them were, and it also offered opportunities to writers who now hold an iconic place in American literature. So, when I showed up, I was able to pursue my interest in African American or Negro history and life and culture, or whatever it was that we were calling it, and Doubleday was really very, very good about allowing me to attend conferences and to cultivate various scholars to produce books and so on. So that was really a very satisfying period for me.

SB: How is it that you became an agent?

MB: I was a senior editor at Doubleday, and I left to become editor-in-chief of a startup Black women’s magazine, Elan, which folded after three issues, and I didn't know what I was going to do then. I tried to find a job in book publishing again, and it was nearly impossible. A number of white editors with whom I had worked had been offered phenomenal jobs, and when I went on interviews, it was as if I couldn’t read. I said, I don't know what you all thought I was doing for these past 10 years with these award-winning books and books that are still in print—and some of them are still in print today. I just was beside myself. Eventually, I ended up working in a bookstore for two years. And I loved it, and I became assistant manager and assistant buyer at Endicott Booksellers, on New York’s Upper West Side.

While I was there, people were calling me and saying, You should be an agent, and I said, I don’t want to be an agent. Editorial was my beat, and I loved it, but I didn’t want to be an agent. And they said, Oh yeah, but now, publishers are requiring most authors who we’re considering to come through agents because we’re receiving too many submissions. So people were saying, We’ll send you authors, and you represent them, and then you’ll get a contract, and you’ll be able to work as an agent, and you’ll see how you like it. It took me a long time to really adjust to being on the other side of the fence, so to speak, when before I was the one who was acquiring books as an editor. Now, I’m trying to sell them to the publisher.

SB: How do you think that your experience, as a Black woman specifically, has shaped your life journey?

MB: That’s a good question, Sara, because I think about it, but I don’t express it often because nobody asks me. But the fact is that I had to make deliberate choices. Looking back, I don’t consider myself an icon, or a survivor, or any of those other titles that have been given to me at this stage of my life, but I was someone who really understood what an opportunity was. And the opportunity was to work in a field that I loved and to stay focused, not to become caught up in being Marie Brown. Because otherwise I would not have been able to do the work, you know? I would just be someone going around and being a role model, at speaking engagements and all of that. So, professionally, I think that I have learned how to be focused. And what I am doing socially is related to all of that; I have been introduced to the best of our cultural world through the work that I’ve done, all various forms of art, whether it’s visual art or performing art, it’s all been integral to my development. Because of publishing, I was able to experience these wonderful aspects of Black life.

And the key to that is Black life. I learned, sometimes the hard way, how to function in that world, that corporate world, that publishing world, but at the same time, I’ve never chose that majority-world life over my community and my culture, because that has strengthened me. When you say, Oh my God, how am I going to get up and do this another day? How am I going to go back into the battle? But it’s the beauty. It’s the beauty of Black life. It’s the challenges of Black life. It’s being able to see what strengths you gain from all of what we have been through.

Harriet Tubman is one of my great, great heroines, and I keep telling people, You can work hard. As a Black woman, look what Harriet did. You wouldn’t even know how to get down your block without a flashlight in a blackout, let alone go through a forest in the woods with snakes and animals and everything and lead people to freedom. So don't tell me you can’t. You can’t do what? You can’t get up and go to work every day? You can’t stay the course? Because I’ve seen so many people quit, just quit, I can’t take it. I have been strengthened by this journey, and the deeper I get into, the knowledge—because books bring knowledge, and what I understand is that they are documents that last for eternities, which is another reason why it’s important for us to be in it, and it’s another reason why I have learned to honor the fact that I’ve been given this responsibility, and I just have to stay the course. And the strength that comes from staying the course is amazing. You don’t know it until you do it.

About the Journalist and Photographer

Turn Inspiration to Action

Consider donating to the National Association of Black Journalists. You can direct your dollars to scholarships and fellowships that support the educational and professional development of aspiring young journalists.

Support The National Caucus & Center on Black Aging. Dedicated to improving the quality of life of older African Americans, NCCBA's educational programs arm them with the tools they need to advocate for themselves.

Credits: Flo Ngala: Erik Carter

This story was created as part of Lift Every Voice, in partnership with Lexus. Lift Every Voice records the wisdom and life experiences of the oldest generation of Black Americans by connecting them with a new generation of Black journalists. The oral history series is running across Hearst magazine, newspaper, and television websites around Juneteenth 2021. Go to oprahdaily.com/lifteveryvoice for the complete portfolio.

You Might Also Like