The lies that built The Bridge on the River Kwai

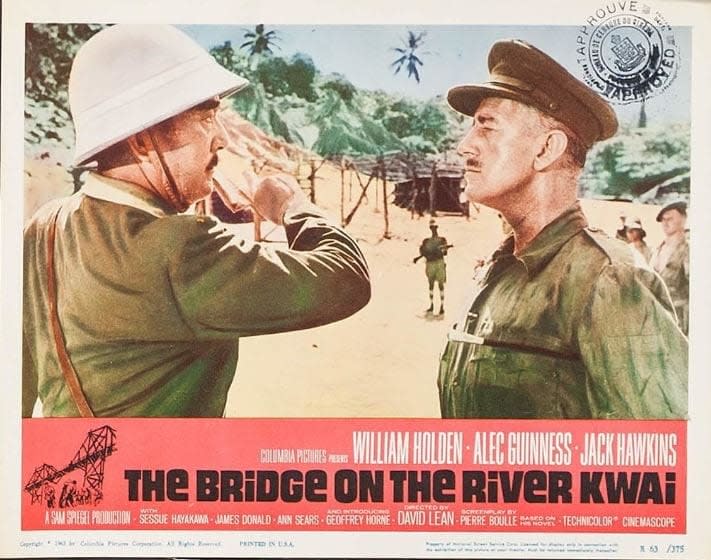

In the early 1970s, Alec Guinness and Sir Philip Toosey were invited to appear together to talk about The Bridge on the River Kwai. Guinness had played a won’t-back-down POW who oversaw the building of the bridge; Toosey was the real-life officer on whom the character was based.

But Toosey declined, by then in poor health and – as described by his granddaughter Julie Summers – very much like other POWs: he didn't speak about his experiences. Guinness also declined.

“My grandfather refused because he felt he couldn’t defend the way the role had been written for Alec Guinness,” Summers tells me. “And Alec Guinness refused because he said it should be [the director] David Lean standing up for the film.”

Indeed, The Bridge on the River Kwai – a five-star classic by anyone’s standards – is more Hollywood fantasy than historical fact. It was no surprise when newly released documents revealed the War Office had been unhappy with the film – particularly its depiction of British soldiers collaborating with their Japanese captors on the notorious Burma Railway.

Producer Sam Spiegel had contacted the War Office, looking for cooperation from the RAF during production. Major A G Close, a former POW working in the War Office’s PR department, wrote: “I do not think much of this story. In the first instance it is quite untrue and only very occasionally resembles the facts as they were at the time. I am perhaps biased as I worked for three-and-a-half years on this particular railway.” He suggested that “it would not go down well with the British public”.

The War Office agreed to RAF co-operation, but insisted that it was “not entirely happy about this film story, which does contain certain inaccuracies and which does not, in our opinion, always authentically portray the behaviour and conduct of British officers”.

The Burma Railway – AKA the “Death Railway” – ran for 415km, and gave the Japanese Imperial Army a direct passage between Burma to Thailand. Its year-long construction, under brutal conditions, claimed the lives of 12,500 Allied workers and around 85,000 Asian labourers.

The film – released in 1957 and based on Pierre Boulle’s novel Le pont de la rivère Kwai – won seven Academy Awards, including Best Actor for Guinness. It tells the story of Lt Col Nicholson (Guinness), who's charged with building a bridge after he arrives at a Burma POW camp. Nicholson refuses to allow his officers to do labour – as per the Geneva Convention rules – which begins a standoff with Colonel Saito (Sessue Hayakawa). Saito throws Nicholson into an iron box – “the oven” – until Nicholson submits.

But Saito underestimates how far the British will go to prove a point, even if it means merrily rotting in a metal box for a week. Saito relents and Nicholson makes building the bridge a matter of patriotic pride, to demonstrate the superiority of British engineering and efficiency. What he doesn’t know is that a team of commandos is on its way to destroy the bridge.

Julie Summers – also a biographer, historian, and the author of The Colonel of Tamarkan: Philip Toosey & The Bridge on the River Kwai – says the film created “quite a lot of unrest” among the POWs who had been there. “It was interesting,” she says. “When my grandfather first saw the film with my mother in 1957, he thought it was a great piece of storytelling. It just wasn’t true. It was only when the prisoners started saying, ‘Sir, it was a terrible slur on your leadership’, that he twigged the public had taken Hollywood for its word.”

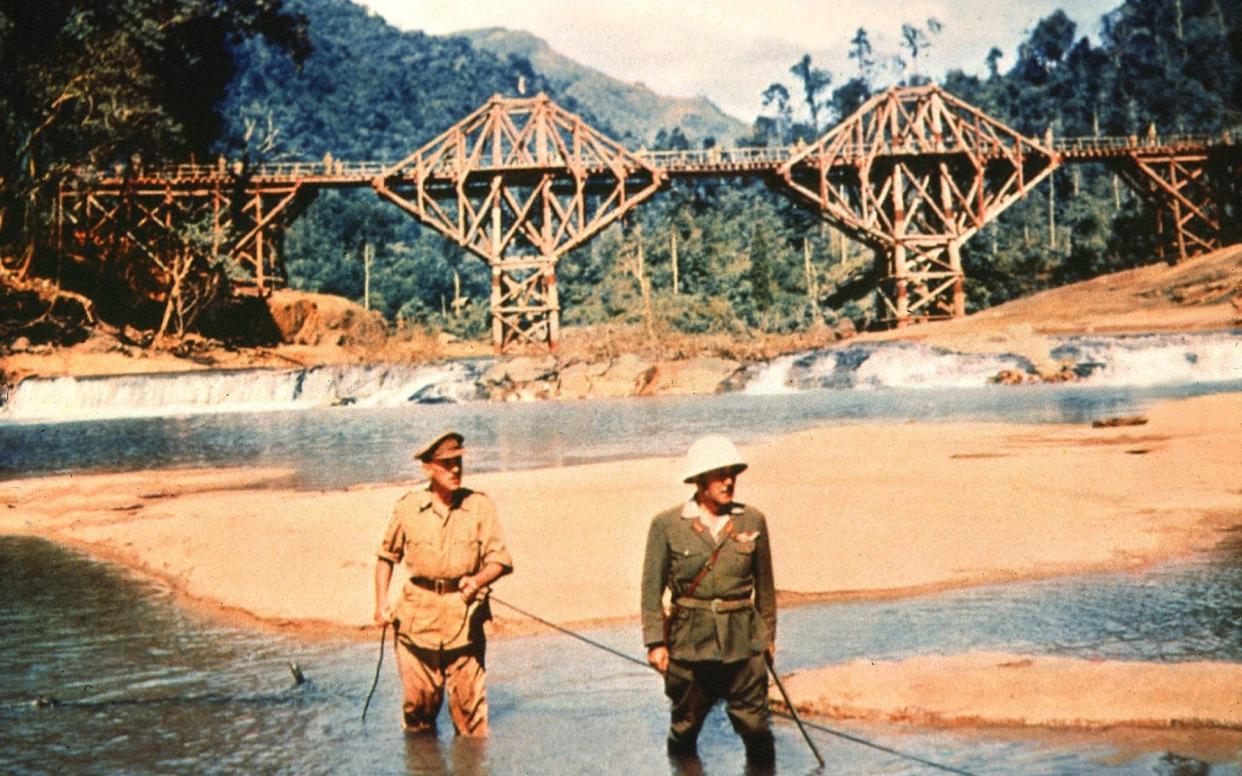

In truth, the POWs, based at the Tamarkan camp, didn’t willingly collaborate for British pride. They built two bridges, not one – a wooden bridge and a steel bridge – across the Mae Klong (the railway ran along the Kwhae Noi, meaning “little river”, which is where the River Kwai name comes from). The bridges also weren’t blown up by gung-ho commandos – in real life or the book.

Philip Toosey was a merchant banker and lieutenant colonel in the Territorials. He was evacuated at Dunkirk in 1940 and was in Singapore when it fell to Japan in February 1942. Toosey refused an order to be evacuated to India and insisted that he remain with his men. He was one of almost 40,000 British and Australian troops taken prisoner in Singapore.

Toosey was sent to Tamarkan on the east side of the Mae Klong, where he was in charge of 2,500 Allied men – British, Australian and Dutch – who worked alongside Asian labour. They heaved around the materials while Japanese engineers did the technical construction. In fact, those engineers were equally as offended by the film; they didn't need British expertise and they'd planned the railway as far back as 1937.

Pierre Boulle (who later wrote Planet of the Apes) had been a POW, though not under the Japanese. He was captured by Vichy French loyalists and held in Hanoi for three-and-a-half years. His book was drawn from his experiences as part of the Free France movement, his time in prison, and firsthand accounts from people who had been on the Burma Railway. David Lean would describe Boulle as making “a great joke against the British when he wrote it”.

After coming aboard the film, Lean disliked the first draft of the script, which was written by Carl Foreman, blacklisted from Hollywood as part of the McCarthy witch hunts. “Poor Monsieur Boulle,” said Lean about Foreman’s adaptation. “If he were dead he would be revolting gently.”

As recalled in David Lean’s biography, there was tension between Lean and Foreman over the script rewrite. They disagreed over the inclusion of the Colonel Bogey tune, which Lean wanted the soldiers to whistle as they marched into the camp. Lean was right, of course: 60 years on, it remains the film’s most well-known moment. Michael Wilson, another blacklisted writer, replaced Foreman. Because of the Hollywood blacklist, Boulle, who couldn't speak English, was credited as the film’s writer and received the Oscar for Best Adapted Screenplay. (Foreman and Wilson would receive their awards, but only posthumously.)

Julie Summers recalls that Philip Toosey saw an early draft of the script and “wasn’t particularly happy”. It featured “hordes of elephants and Burmese girls and goodness knows what”. Spiegel insisted on another inaccuracy: an American hero, played by William Holden – a chancer who escapes from the camp but returns to destroy the bridge.

The film was shot in Ceylon (now Sri Lanka), where a bridge had to be built. Piers Paul Read’s 2003 biography of Alec Guinness describes how the shoot was “an unpleasant experience for all concerned”.

He wrote: “The heat, the humidity, the poisonous snakes and centipedes, the logistical demands of building such a complex set in the middle of the jungle, were compounded by ill-temper and bad luck.”

Lean and Guinness fell out. At one point Guinness questioned why Lean was shooting one of his best scenes from behind. Afterwards, Lean (who was English but in tax exile) said: “Now you can all f--- off and go home, you English actors.” Guinness wasn’t alone. “By the end of the picture,” the cameraman Peter Newbrook remembered later, “there were probably only four people that David wanted to talk to.”

There were serious accidents during production. Both Lean and a stuntman almost drowned in separate incidents; a car crash killed second-unit director John Kerrison and broke make-up artist Stuart Freeborn’s spine in two places.

For the film’s climax, in which the commandos blow up the bridge, the Prime Minister of Ceylon, Solomon Bandaranaike, came to witness the spectacle, as did crowds of dignitaries, ministers and businessmen. But Lean had to abandon the explosion at literally the final seconds – he wasn’t sure that all of his cameramen were clear of the blast zone.

It caused Sam Spiegel, with whom Lean had also fallen out, considerable embarrassment. The shot had to be completed the following day. (Spiegel would often say that the explosion cost $250,000, though Julie Summers says that her research found the actual cost was around $53,000. “Why spoil a good story?” she jokes.)

After patching things up, Lean previewed the film for Guinness and his family. They watched quietly and left. Afterwards, Guinness told Lean it was “the best thing I’ve ever done”. And The Bridge on the River Kwai is, of course, magnificent. It’s Guinness, not the bridge, which stands as a monument to exemplary Britishness: stubborn, pompous, and by-the-book to the point of bloody-mindedness. During his standoff with Saito, he won’t even be bribed with a nice chunk of corned beef. “I hate the British!” shouts the infuriated Saito.

Guinness was reportedly concerned with the film being anti-British; on the contrary, its Britishness is something to be reveled in. “Colonel, do you suppose we could have a cup of tea?” he says, getting his priorities straight before starting work on the Death Railway.

Julie Summers laughs that Guinness’s Nicholson is “a bit of a bonehead… an archetypal British solider”. When asked about the difference in personality between Guinness’s character and Philip Toosey, Summers says: “I think the fundamental difference is that Alec Guinness was all about the bridge and my grandfather was all about the men.”

In truth, there had been low-level attempts by the soldiers at Tarkaman to sabotage the bridges. They collected termites to put into the foundations of the wooden bridge, or mixed cement badly. (“It’s very easy to make a right charlie of cement,” Toosey said.) But their efforts were more about boosting morale than serious attempts to hold up the railway construction.

“The Japanese were superb engineers and the guards were brutal all along the railway,” Summers says. “They were on the prisoners’ backs the whole time. My grandfather wasn’t trying to build the bridge well or badly for them. He was there to protect his men. That was his complete focus. He saw it as his duty to get as many of them home as safely as possible.”

Toosey’s men were under-fed, overworked, and afflicted with illnesses during the construction of the bridges. But his influence ensured that the conditions at his camp were better than at others, many of which were hit with dysentery, beriberi and cholera. The death rate along the railway was 27 per cent, but just a handful of men at Toosey’s camp died.

A shrewd and likeable negotiator, Toosey secured rest days, better food and a canteen for his men. He rejected military formalities by refusing to have an officers’ mess or separate sleeping quarters, which Summers has described as “practically heretical” for 1942. Toosey also taxed his officers’ pay, and used proceeds from the canteen to pay for medical supplies.

“But he kept the army discipline of hygiene and morale very strictly,” Summers says. “He knew if there were a breakdown in discipline, that could lead to riots or attacks on the officers, like it did in the other camps. Some people thought he was a martinet. I don’t think he was, but he was clear that there were rules to be obeyed. Rules that didn’t have to be obeyed, such as preference for the officers, were ignored.”

Watching The Bridge on the River Kwai in 2020, it’s amusing that Nicholson’s defiant stand against Saito, for which the men whoop and cheer, is a fight for preferential treatment for elite officers, while the regular soldiers have to muck in with the slave work. There was no such stance. After the Fall of Singapore, Lt Gen Arther Ernest Percival, who became chairman of the Far East Prisoners of War (Fepow), reluctantly agreed that Allied men would be used for labour.

In the film, Nicholson forbids anyone from attempting to escape. The real soldiers signed a document – under duress and therefore illegally, Summers points out – agreeing they wouldn’t attempt to escape. Some soldiers and officers did escape from the camp but were recaptured. They were taken out into the jungles and forced to dig their own graves before being killed. The soldiers were shot, the officers bayoneted. “My grandfather said it was terrible,” says Summers. “The look of loss in their eyes as they were driven away. They knew they were going to be killed.”

Toosey himself faced brutal treatment from the Japanese guards, largely for complaining about beatings his men suffered. “Almost inevitably, he’d get hit over his head,” Summers says. “He wasn’t tortured but bashed about. He was made once to stand outside the guard hut in boiling sun for 24 hours. There were times when he thought, ‘I can’t go to that guard hut again… no, the men need me to!’”

Toosey wasn’t locked in “the oven”. But a similar thing happened to a translator, Capt William Drower, who upset his captors. His arm was broken and he was imprisoned in an underground hovel for 76 days. While in there, a rat ate into his foot.

When Toosey saw Alec Guinness confronting Saito in the film, he said: “You could never have confronted the Japanese and caused them to lose face. That would have been fatal. I would not have survived.” There was a real Saito at Tamarkan, though the name connection is likely coincidental. Toosey thought the real Saito was “fair”, and spoke up in his defence after the war.

The issue that most upset survivors of the Burma Railway is the depiction of British soldiers collaborating with their Japanese captors. Was there any collaboration?

“There were people,” Summers says, “who collaborated with the Japanese in order to make their own lives easier. There are people who thought my grandfather was a collaborator because he was prepared to negotiate and speak to the Japanese. It’s a terribly fine line. What he wanted to do is keep his men as safe as possible. He certainly didn’t think he had collaborated with the Japanese. It would have been a harsh judgment to say that he had.”

The wooden bridge was completed by February 1943 and the steel bridge in May 1943. Afterwards, Toosey turned Tamarkan into a hospital and took his biggest risk yet: he smuggled medicine from Bangkok in baskets of fruit. He was later posted to sites at Nong Pladuk and Kanchanaburi.

The wooden bridge was hit by bombs nine times and rebuilt nine times. The steel bridge was hit by the US Air Force in 1945 and rebuilt. It still stands today, and that part of the Mae Klong has been renamed the Khwae Yai.

Toosey died in December 1975, aged 71. In 1984, Saito came to Britain and visited Toosey’s grave. “He changed the philosophy of my life,” said Saito about Toosey. “I understand that he knew what it was to be a man. He didn’t judge people.”

Lt General Percival disliked the film and said he wanted it banned, and Summers explains that the POWs wanted the film-makers to include a statement explaining that the film was based on a book, and not the true story. “But they never did,” she says. “And why would they? It’s Hollywood. They were out to make the greatest war movie of all time – and some would say they succeeded.”