This Less-visited Destination in Indonesia Has Celebrated Street Food, Eco-conscious Boutique Hotels, and Access to the World’s Largest Buddhist Temple

As Indonesia opens to visitors again, one woman returns to the island where she lived years ago — and remembers why the enchanting, energetic Yogyakarta region is an essential stop.

From left: Terence Carter; Courtesy of Aman

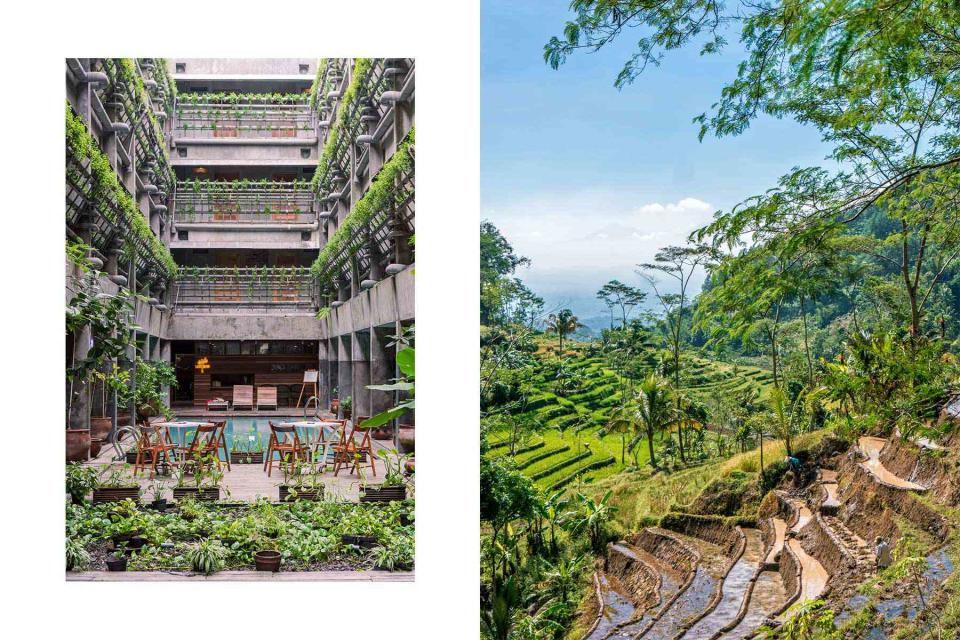

From left: The atrium at Greenhost Boutique Hotel; the rice terraces surrounding Selogriyo, a small Hindu temple between Jogja and Semarang.When people think of Indonesia, they often picture Bali and its picturesque beaches. But as I sat aboard a train on the neighboring island of Java, passing rice terraces, ancient temples, and glorious expanses of forest overlooked by towering mountains, I wondered: why not here, too?

Java is home to more than 140 million people, making it the world’s most populous island. In 2016 I spent a year living in the province of Central Java, where I taught English at a military boarding school in Semarang, a port city on the northern coast. During my time there, I fell in love with Java’s national parks, ancient temples, and dynamic cities — and I returned for the first time this past August, seeking to reconnect.

Some of my most memorable experiences had occurred in Yogyakarta, a storied city about 350 miles east of Jakarta, Indonesia’s densely populated capital. In “Jogja,” as locals call it, I found a compelling amalgam of historic architecture, resilient Javanese culinary traditions, and creative spirit — with a burgeoning population of young people eager to revamp the status quo.

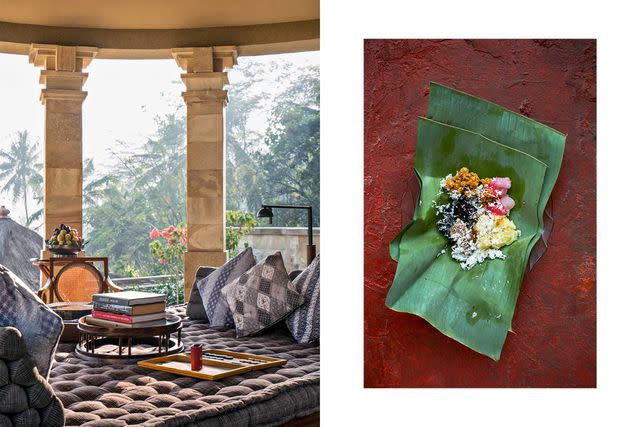

Here, street food is culture, and culture is king. It seemed only right that I would begin my return trip on the hunt for jajan pasar, the traditional Javanese cakes so delightful they’ve become synonymous with the city. My friend, the Indonesian food scholar Kevindra Prianto Soemantri, explained that the sweets come in a range of colors but are usually made from a four-ingredient foundation: cassava, palm sugar, coconut, and sticky rice or rice flour.

haryanta.p/Shutterstock

The central market in Jogja’s historic Kotagede neighborhood.Mbah Satinem’s food stall Lupis Mbah Satinem, in the Jetis district, is known as one of the best places to enjoy jajan pasar; the elder has been making the cakes for more than 50 years, charming visitors with her confectionary intellect. (On Soemantri’s recommendation, Satinem appeared in the Netflix series Street Food: Asia in 2019.)

The sweets are just one example of how food permeates the streets of Jogja, where satay, gudeg (braised jackfruit), and kopi joss (coffee with charcoal) take center stage. There was even food growing on the roof of my hotel: cabbage, spinach, mint, and basil, among other herbs and leafy greens. During my stay at Greenhost Boutique Hotel, in the popular Prawirotaman area, I chatted with assistant manager Pak Surya, who told me all about the goal of providing affordable accommodation that was also eco-conscious. “We’ve figured out how to naturally cool the building,” Surya said as we stood by the pool in the atrium, surrounded by towering greenery. He pointed up to the garden above, which was releasing mist into the atrium. In a country that’s battled pollution, deforestation, and other environmental challenges, it was a lush sign of promise.

This sense of invention runs deep within the area’s artistic community, too. The Jogja National Museum provides a stage for contemporary artists from Java and other Indonesian islands with rotating exhibitions and performances (and even opened its own guesthouse, Casa Wirabrajan, during the pandemic). In the nearby city of Magelang, the OHD Museum is a lesson in cultural reclamation: it displays the acquisitions of private collector Oei Hong Djien, known for gathering modern and contemporary Indonesian art from around the world — including pieces by pioneers like Raden Saleh and Ahmad Sadali — and bringing it back home.

From left: Courtesy of Aman; Martin Westlake

From left: A reading nook in the Dalem Jiwo suite at Amanjiwo, a secluded resort in Central Java; jajan pasar, often served on a banana leaf, is a common market treat.I was in Jogja during Artjog, a contemporary art fair, where highlights included Catatan Pinggir Jurang, a dreamlike pillow installation by Alex Abbad and Angki Purbandono, and Borobudur–Expanding Unawareness, a dark room with neon-bright renderings of Buddhist statues and temple-goers. The latter was put together by Nawa Tunggal and his brother, the painter Dwi Putro, whose work draws on his experience with schizophrenia. Later, visiting the Hindu temple complex at Prambanan, just outside the city, I saw the ancient stone reliefs in a new way.

Jogja’s creative streak was on full display at Mil’s Kitchen, where chef Mili Hendratno combines his global culinary experience (including a stint with Kempinski Hotels) with an unabashed focus on Indonesian produce and flavors. Slices of Wagyu pastrami were bathed in sambal-spiked mayonnaise and pressed against gently toasted focaccia. Gohu ikan gendar, a ceviche inspired by the eastern Indonesian island of Ternate, was paired with crispy rice chips. Wagyu cheeks with bone marrow delivered on both presentation and flavor: plated on a bed of multicolored rocks, the smoky dish was dotted with a rich coffee-miso reduction and topped with a bright lime, pickle, and shallot glaze.

“Indonesia has the most incredible flavors, the most incredible way of doing things,” Hendratno told me. “I’m trying to showcase the range of our technique, and of what we can do in the kitchen.”

The five-course meal was exceptional fuel for the remaining action-filled days of my trip, when I headed out of the city to Amanjiwo, a 31-suite resort in the hills an hour northwest of Jogja. My friend Anna Grundström also happened to be in Java, on a journey to reconnect with her Indonesian heritage, and we met up for a few Aman-coordinated tours in the more rural parts of the region. It was a comfortable, hour-long taxi ride from the city to what is, for many visitors, the main event: Borobudur, a UNESCO World Heritage site containing the world’s largest Buddhist temple — likely opened in the ninth century, and restored in the 20th — that’s also one of Indonesia’s most visited tourist attractions.

Martin Westlake

Ninth-century buildings at Prambanan, the largest Hindu temple complex in Indonesia.“It took about a hundred years to build,” our guide, Hasan Bisri, told us. “When you see Borobudur from a helicopter, it looks like a lotus.” Visitors were once able to walk through the temple’s nine stacked platforms, which hold stunning Buddhist statues and numerous relief panels, but graffiti and physical damage, as well as the ongoing pandemic, have restricted guides to showing guests around the ground level. Nonetheless, Bisri, who has worked at the temple since 1988, was thrilled to once again be giving tours to international visitors.

Anna, who was visiting Indonesia for the first time, was in awe. I was transported back to my first visit to Borobudur, five years earlier, when I’d watched the sun rise over a row of life-size Buddhas. Much is different in my life now — relationships have evolved, homes have changed, the world is somehow even more complicated — but my feelings about Borobudur have remained the same. This marvel, constructed from lava rock from a nearby volcano, is a testament to human strength, and a portrait of a society trying to figure it all out. I imagine the people of the eighth and ninth centuries turning to the teachings of Buddhism and Hinduism to navigate their own challenges, many of which we’re still navigating today. Amid their struggles, they managed to live, thrive, and create something beautiful. It’s what humans have been doing forever, and what we’ll continue to do, even in our seemingly darkest days.

Amanjiwo overlooks the most stunning ruins of Borobudur, its suites nestled against majestic Menoreh Hill in a remote area of Central Java. I have no qualms about admitting my sybaritic inclinations, and the resort had no qualms indulging them: I was greeted by flower-throwing employees who offered me a refreshing bowl of watermelon before walking me to my high-ceilinged suite, which opened out onto a private garden.

After enjoying my plush room for a few hours, the Aman arranged a visit to the home of chef Pak Bilal, whose son, Pak Damar, now runs the show. Against a backdrop of gamelan music, Damar prepared a sumptuous, comforting tasting menu that left me speechless: prawns in a steaming bowl of soup with wood-ear mushrooms, grilled chicken marinated in cilantro and lemongrass, a Javanese fish curry, grilled tofu wrapped in banana leaves and served with shredded coconut and lime. The culinary performance ended with Damar’s own selection of jajan pasar, including dadar gulung, a crêpelike pastry flavored with pandan leaf and stuffed with caramelized coconut.

Normal people — people with common sense — would go back to their luxury hotel room, grab a book from the nightstand, and slowly settle into their upper-thousands thread-count sheets. I, however, opted to see more of this massive island — even if it meant a possible bout of hypothermia. Anna, who was staying in a guesthouse nearby, met me at 10 p.m. for a three-hour drive to the base of Central Java’s Mount Prau, one of Indonesia’s many volcanoes. The dormant peak stretches to 8,415 feet above sea level. After a cold, hours-long hike through the Dieng Plateau, wondrous views awaited us.

I imagine the people of the eighth and ninth centuries managing to live, thrive, and create, even amid all their struggles. It’s what humans have been doing forever.

Courtesy of Aman

The sun rises over the ninth-century Buddhist temple at Borobudur.At the summit, Anna and I snuggled into a tent while our guide, Pak Hariyadi, and two assistants prepared piping-hot noodles and tea. As the light began to emerge, we stood in the windy expanse and watched the sun rise over the earth. It was entrancing — I felt I could almost reach out and grab the nearest cloud, or touch the other, even taller volcanoes nearby. We lingered, grappling with the sheer enormity of our world, and then made our way back down.

At the resort that evening, Anna joined me for a staging of the Kakawin Ramayana, an epic poem that emerged in Java in the eighth or ninth century and is still performed throughout Indonesia. The private performance was accompanied by a traditional meal, which included delicacies like udang bakar kalasan, grilled prawns marinated in local coconut milk. We devoured every dish as we watched the dancers move with indisputable passion and skill.

“A lot of people come to Indonesia to engage with spiritualism and mysticism,” Aman’s resident anthropologist, Patrick Vanhoebrouck, had told me over tea the previous day. “They go straight to Bali to look for this — not realizing that the heart of it is right here, on Java.” Enjoying one last swim before heading to the airport, pausing after a few laps in the infinity pool to take in the surrounding hills, I felt like I was at the very center of it all.

A version of this story first appeared in the December 2022/January 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Javanese Jewels."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.