Can Leicester Beat Fast Fashion—Boohoo Included—and Save Made in the U.K.?

When Boohoo Group inaugurated its first wholly owned manufacturing facility in the English city of Leicester to massive fanfare—ribbon-snipping ceremony, polished signage dignitaries and all—in early 2022, the 23,000-square-foot space was hailed by the e-tail giant’s CEO as nothing short of a “landmark moment” for made in Britain.

“This is a very visible demonstration of our commitment to Leicester and U.K. garment manufacturing,” said John Lyttle, who was joined by Peter Soulsby, the mayor of Leicester; Kevin McKeever, chair of the Garment & Textile Workers’ Trust; and Tim Nelson, CEO of the nonprofit Hope for Justice. “By operating the site as a center of excellence, we want to bring back skills that have been lost over time and help our suppliers to diversify their product offerings, meaning they can win business from other retailers who we are hoping will be tempted to start sourcing from the U.K.”

More from Sourcing Journal

The facility would spawn jobs for 180 workers who would operate across two shifts, generating “double the job opportunities” and greater flexibility, the Nasty Gal and PrettyLittleThing owner said at the time. No shadow of the sweatshops that dogged the company in 2020 here: Employees would be guaranteed 40-hour contracts, 33 days of paid vacation, private medical care, free company shares, a generous discount on all brands across Boohoo’s portfolio, “excellent” training and development, and opportunities for overtime when “production requires” for the 20,000 garments it would spit out per week. Lyttle called it “more than just a factory” but rather a “hub of learning and collaboration,” one that would provide its employees with the experience of a working shop floor while buttressing its relationships with approved local suppliers, which by that point had been vigorously culled from 500 to less than a hundred to just under 50.

Less than two years later, Boohoo is considering packing up the Thurmaston Lane plant and decamping some of the 100 positions that it says remain, though sources familiar with the situation suspect that most, if not all, of those workers, have already been given the sack. Many of those jobs involved end-to-end garment manufacturing, such as cutting, sewing and digital printing.

Circumstances have changed, a spokesperson said of the news, which was first reported by Drapers last week. With Boohoo making “significant” investments at its Sheffield distribution center, plus a newly opened one in the United States, it “must now take steps to continue to ensure we are a more efficient, productive and strengthened business.” Now, the Debenham’s operator is in a “period of consultation,” where it’s considering the closure of the site “in due course.” The spokesperson added: “We are working closely with all affected colleagues to ensure they are fully supported during this process.”

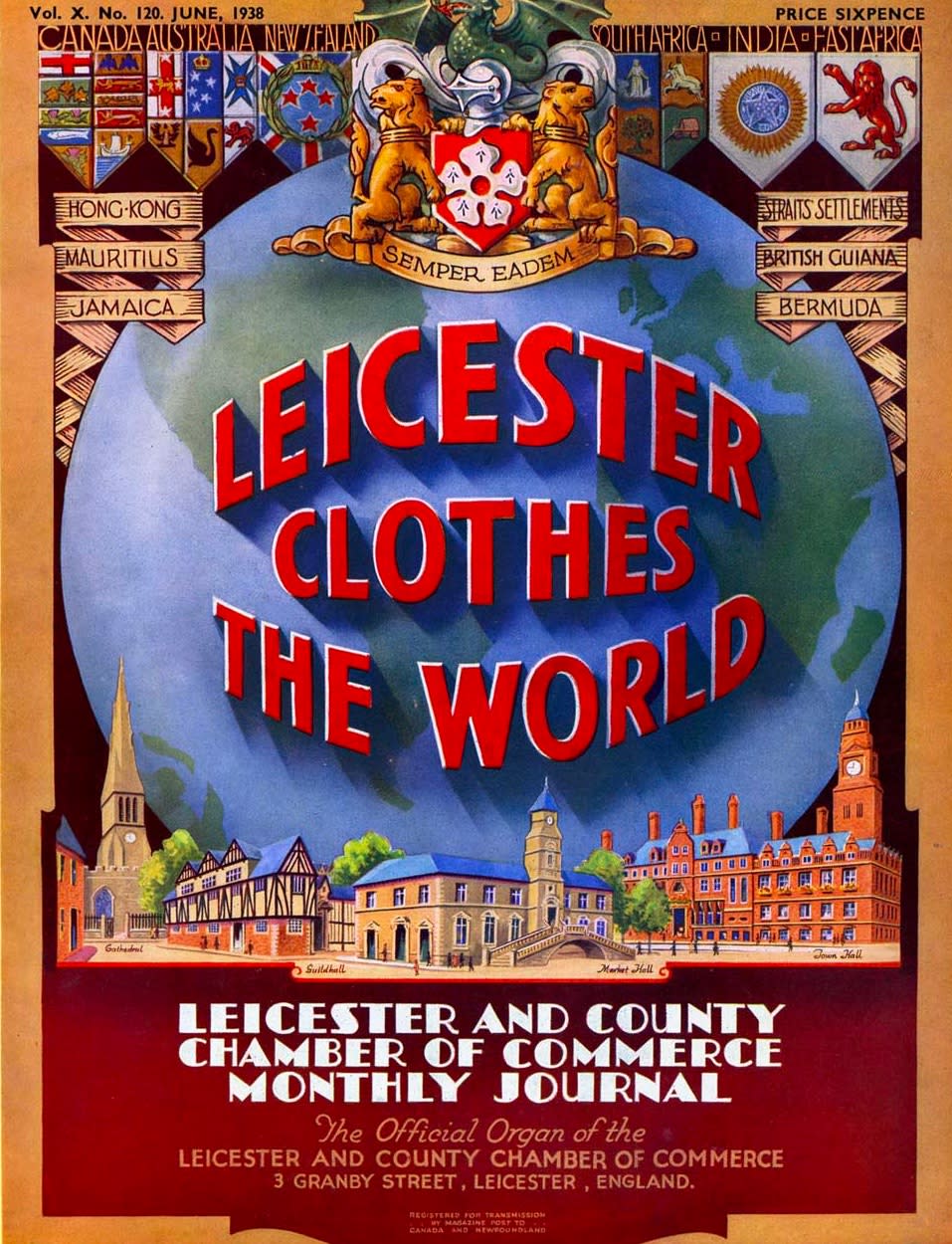

The model facility was one reason that Brian Leveson, the retired High Court judge who oversaw the overhaul of Boohoo’s business practices, known as its Agenda For Change, declared it ready for “business as usual” in his final missive to the board in February 2022. The company’s ethical compliance team, he said, operates from Thurmaston Lane from where it “exercises responsibility for daily sourcing and compliance checks,” he said. Its “template” of open costings also demonstrates the “extent of the journey that Boohoo has undertaken since mid-2020,” when allegations of dangerous working conditions and poverty pay proliferated among its Leicester suppliers—allegations that a Boohoo-commissioned review by Alison Levitt, a former legal advisor to the Crown Prosecution Service, found to be “substantially true.” Leveson praised the plant as emblematic of the “determination of Boohoo to stand behind the city,” once a place that “clothed the world,” particularly after the Industrial Revolution, now a shade of its former self with shuttered factories and stilled machinery.

On a brisk morning in October, Sajjad Khan, founder and chairman of the Apparel & Textile Manufacturers Federation, drove down streets with names like St. Saviour’s Rd. and London St., where garment manufacturing once thrived among Leicester’s majority South Asian population. An eerie quiet permeates an area once characterized by frenetic activity.

“There’s not many factories left here,” he said, gesturing from one brick structure to another. “These all used to be factories at one time employing thousands of people and now they’re all empty. They’ve all been decimated. All the business has disappeared from here.” Khan paused, eyes flicking down to the steering wheel. “There was a time in Leicester that you couldn’t get people to work in the factories because there were not enough people available,” he said. “Now there is an oversupply of people with no work.”

Khan, a “Leicester boy” who was until December the owner of the leisurewear supplier Aristec, which he has since closed, estimates that the number of factories has nosedived from 1,000 to little more than 200, if that, in recent years. Even Boohoo, once a tentpole customer, is increasingly whisking its business off to “near-shore” destinations such as Morocco, Turkey and Tunisia, where the cost of labor is cheaper and regulatory and media scrutiny less acute. While trial runs and small batches might still take place in Leicester for expediency’s sake, this has turned the city into more of a service center than a production hub, he said, adding, “We are able to facilitate production within two weeks, sometimes within a week if necessary.”

That a purveyor of $5 halter tops and the final resting place of King Richard III should be so intertwined is down to a quirk of fate. It was the advent of globalization and free trade that set off Leicester’s downturn by funneling orders to cheaper climes overseas. Then came Brexit and its increased tariff barriers to trade, making the United Kingdom even less attractive as a sourcing locale for European retailers. Founded in 2006 by Mahmud Kamani and Carol Kane, Boohoo, which did wholesale work for the likes of Primark and New Look, saw an opportunity in Leicester’s speed to market as fashion e-commerce took off. It turned out to be the city’s “savior” at a time when work was scarce, making up, at one point, 60-70 percent of the 2 million garments being churned out every week, Khan said. But Covid-19 marked a turning point when orders started drying up because of flagging consumer demand. It was the bad publicity, however, that proved to be a body blow from which it has yet to recover.

“I was a bit disappointed because of the whole media focus on manufacturers being the bad guy in all of this,” he said. “There were some fantastic factories in Leicester and it’s unfortunate that they’re all being tarnished with the same brush. This had a huge impact on their production—they had to lay people off, reduce their production capacity. All of a sudden they didn’t have any work because brands were pulling out. And as much as the NGOs have tried to help, they also have been a hindrance.”

A promise broken?

Damaging news continues to trail Boohoo. A BBC Panorama investigation in November, headlined “Boohoo Breaks Promises on Ethical Overhaul,” revealed that hundreds of orders placed with the facility were being outsourced to Morocco and other parts of Leicester. At Boohoo’s headquarters in nearby Manchester, an undercover journalist for the news program witnessed employees pressuring suppliers to lower prices by as much as 10 percent, even after agreements had been made. Sometimes these discounts were unilaterally imposed, the reporter said.

“Boohoo has not shied away from dealing with the problems of the past and we have invested significant time, effort and resources into driving positive change across every aspect of our business and supply chain,” its spokesperson said by way of response, adding that it has, under Leveson’s supervision, implemented every recommendation provided by the Levitt review. “The action we’ve taken has already delivered significant change and we will continue to deliver on the commitments we’ve made.”

This week, BBC Panorama dropped another bombshell, claiming that Boohoo stitched “Made in the U.K.” labels on possibly thousands of items that were made in Pakistan and then shipped to Thurmaston Lane. The Boohoo spokesperson said this was an “isolated incident,” born of “human error,” that affected fewer than 1 percent of its garments, and that it has taken steps to ensure “this did not happen again.” The representative also said that BBC Panorama’s earlier findings had no bearing on its ongoing judgment of its Leicester facility.

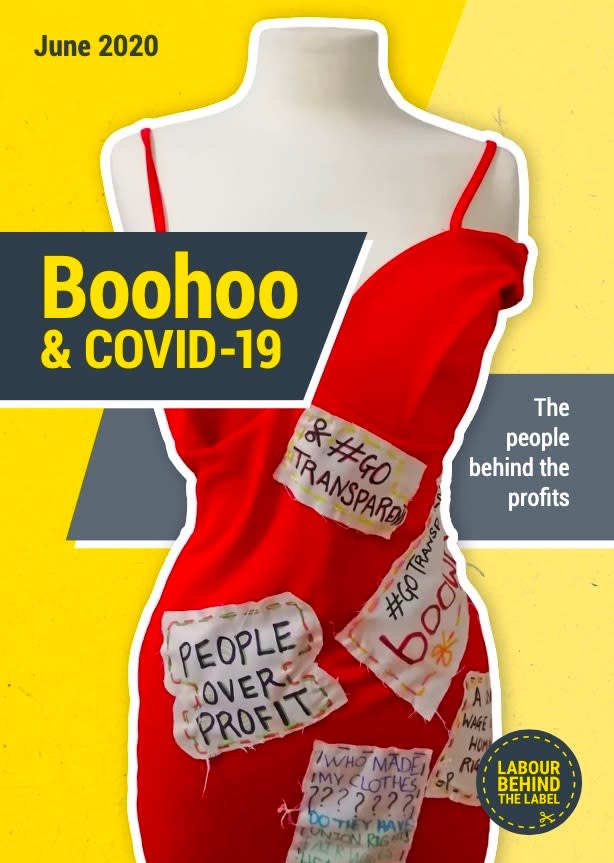

But Dominique Muller, policy director at the Bristol-based workers’ advocacy group Labour Behind the Label, has questions for Boohoo, like she usually does. It was her organization that published a report in June 2020 alleging that the company’s suppliers were paying workers as little as $3.80 a day. Those factories also stayed open during the Covid-19 lockdown, putting their employees at risk of infection, or even death, it said.

“I would ask why they couldn’t make it work [now] but managed to make it work before 2021—was it perchance due to underpaying U.K. workers to the tune of [$64 million] per year that helped them make a profit?” she said. “The closure suggests their business model is only sustainable when it can utilize cheap labor and low standards of social protection in countries with limited scrutiny.”

“It’s very sad for the workers who were promised sustainable jobs,” she added.

In a December survey of 350 British shoppers, a whopping 56 percent of respondents declared Boohoo the “least trusted U.K. fashion brand.” While this may be true, ethics has less to do with Boohoo’s post-scandal downward slide, than with “rising” competition from “dynamic” players like Shein, said Pippa Stephens, senior apparel analyst at the data analytics company GlobalData.

Certainly, the Chinese e-tailer has its share of ethical hotspots, yet its U.K. market share rose 0.6 points to 2.2 percent in 2023, with its extremely low prices and fast turnaround continuing to “help it capture the attention of new shoppers.” In contrast, Boohoo tumbled by 0.4 points to 1.7 percent, as “their product offers struggle to hit the mark with their core customers.”

The results of a GlobalData survey of 10,000 U.K. consumers from June bore this out. Nearly 90 percent of respondents rated price and value for money as their most important considerations when triggering a purchase, compared with 57 percent who valued retailer ethics. This disparity is only going to increase as Britain’s cost-of-living crisis deepens, Stephens said.

In Khan’s opinion, Thurmaston Lane was just a failed PR exercise for Boohoo. Even if it was making 20,000 garments a week, what is that to the 1.2 million or so that it was producing in Leicester at its height? “It was a false economy,” he said.

Still, Boohoo isn’t the only brand to blame for the city’s diminished position as a textile center. Others, too, have been “complicit” in not paying prices that can sustain livelihoods in the United Kingdom, Khan said. Instead, they fed off suppliers’ desperation to stay afloat, even if it meant taking on orders that paid “less than break even.” But this wasn’t a new problem—manufacturers sounded the alarm 15 years ago, 10 years ago, yet nobody listened. Then when the Boohoo imbroglio blew up and continued blowing up due to the speed and breadth of social media, it was the suppliers who became the “bad guys.”

‘Normalized’ exploitation

That’s not to say that worker exploitation doesn’t take place in Leicester. New immigrants are coming into the city all the time and garment work, which doesn’t require extensive training or a grasp of the English language, is easy to fall into, said Kaenat Issufo, community engagement lead at Labour Behind the Label. At the same time, their status, lack of an existing support structure and inability to advocate for themselves make them vulnerable to exploitation. Many accept low wages or informal contracts because they don’t know better, are hungry for a job or fear that complaining might result in deportation.

Issufo should know. When her family arrived from India to Leicester when she was nine years old, her mother and older sisters became garment workers. She had to translate for her parents using what she learned in school.

“The struggle we went through is something every family in our community goes through when they come to the U.K.,” she said.

According to a University of Leicester study based on 2021 census data, 42 percent of the city’s residents were born outside the United Kingdom, with India, Somalia and Poland being the most common countries of origin between 2011 and 2021.

Those who start in the garment industry tend to stay there in a kind of stasis. They often work long hours in order to make a “regular person’s wage,” Issufo said. This means they have little time to improve themselves, whether it’s taking English classes or learning computer skills.

“They’re stuck for many, many years,” she said. “And then the situation becomes normalized for them that they used to being exploited. And it’s accepted because [unsavory manufacturers] know that there’s always people coming into Leicester and always looking for jobs. There is always a queue of people waiting to be employed by these suppliers in Leicester.”

For every legitimate business, there is an “undercover” outfit that operates off the books and away from prying eyes.

“Normalized” was the same word used in a 2022 survey of 116 of the city’s garment workers by the University of Nottingham’s Rights Lab and De Montfort University. Notably, the study was commissioned by the Garment and Textile Workers Trust, a board of trustees-led body that Boohoo helped establish with a $1.4 million infusion when it was working to repair its reputation. In it, 56 percent of respondents said they were paid below minimum wage, 55 percent didn’t collect holiday pay and 49 percent didn’t get sick pay. Nearly one-third, or 32 percent, didn’t receive payslips or work contracts, and 24 percent said they were forbidden from taking days off. Some reported feeling pressured to work up to 14 hours a shift. Others noted discrepancies in what their wage slips showed and the amount they actually received.

“It’s a lot of people of color in the garment industry,” Issufo said. “They’re the ones being exploited by the global North, even though they’re in the global North. They give 15, 20, 25, sometimes even 30 years of their life to this industry. And what they get back are job losses, unfair dismissals, unpaid wages or redundancies.”

A ‘dying trade’

The lead-up to Halloween and Christmas is usually the busiest time of year in Leicester. At one screen-printing and flocking business, however, $5 million worth of machinery that once whirled shirts and sweaters like dervishes for boldface names like Primark, New Look and T.K. Maxx, were unaccountably still.

“Normally, you come to my floor, I’ll be so busy with last-minute Halloween orders,” said the owner, who asked to remain anonymous to preserve the little business he has left. Before the pandemic reared its head, he was pumping out close to half a million tops replete with witches, ghouls and goblins. This year, he hasn’t printed a single one.

“Right now I should be busy with Christmas prints,” he said. “Now I’ve got three orders for Christmas, when we usually do over 100, 200,000 garments for Christmas.”

The supplier runs what he describes as an ethical shop, but this isn’t an easy thing to do, since the things that brands send auditors to look for—minimum wages, which will go up again this April to $14 an hour; health and safety; compliance—come at a frequently hefty cost. “They want you to be ethical, but at the same time, they want to give you unethical prices,” he said. “So how do you survive?”

A couple of the machines are being dismantled in preparation for a move to Morocco, where many Leicester manufacturers are relocating, the owner said. No matter how you do the math, there’s simply no way U.K. manufacturing can compete with Morocco, Bangladesh or Pakistan for that matter, even though some of the shortcuts he has seen on those production lines should make brands blanche. Someone is buying the equipment from him but he’s considering moving as well. At one point, the plant used to employ 110 workers pouring over 80,000 meters of material per week. Today, it’s on life support with 28 staffers, himself included, and he’s lucky if he runs through 300-500 meters a week.

“When I look at this clothing industry, it reminds me of the shoe industry, the engineering industry, how they slowly deteriorated,” the supplier said. “Slowly, everything is going abroad. It’s a dying trade, basically.”

Leicester’s suppliers broadly agree that the furor over Boohoo’s “sweatshops” was likely the final nail in the coffin, albeit not the only one. At a vertically integrated facility on the other side of Thurmaston Lane, a supplier who has made garments for Missguided, River Island, and yes, Boohoo, recounted a conversation over costing that still surprises him. “I don’t care how you get it done,” a sourcing executive told him. “As long as the paperwork is right.” The person, he stressed, wasn’t from Boohoo.

“Everyone that comes wants to talk about Boohoo, but you need to talk about the other stores; you need to talk about River Island, you need to talk about New Look, you need to talk about Asda,” said the supplier, who also asked not to be named. “Because we’ve worked with them all and there’s no one different. Boohoo’s price points might be lower than those stores but they’re all screwing you for the same things as well.”

The manufacturer had the opportunity to move to Morocco, but he wouldn’t entertain the thought. “I want to fly the British flag,” he said. “I am proud that we are making in the U.K. [Look at] Italy; they’re proud of their heritage and they get a premium for [their goods]. Why is somebody happy to buy a Prada T-shirt made in Italy? Why can’t we make Burberry in the U.K.? So yes, this is where we need to be.”

His USP, or unique selling point, is that everything is in a five-mile radius. “From this building, within five radial miles, I can have my fabric knitted, I can have my fabric dyed, I can manufacture and I can ship,” he said. “I don’t think anyone else has a carbon footprint as small as what I have.” But orders have taken a beating here, too. The factory was doing upward of 40,000 units every week at its peak. It’s down to at most 2,000 on a good week.

Meanwhile, he’s shunning the high street. If those brands can’t make his economics work, he won’t work for them. Economics are also the reason he’s shifting to digital printing over screen printing, as well as increasingly opting for automation. “Nobody wants to get dirty anymore,” the owner said. “I’m not going to lie. I can’t wait till the day a robot can make a whole garment. That will help with costing and I’ll have less of a headache in terms of HR.”

Khan agrees that automation is the right tack. He said the industry has gotten rid of the “bad apples” to a large extent. “The more we can automate things and produce a better quality product, the less of those unscrupulous people will be around because there is no way for them to bend the rules and make a profit by doing something in a different way,” he added.

The Apparel & Textile Manufacturers Federation has been lobbying the city council for an “eco-park” that focuses on high-value garments. Khan has lined up an American brand that is interested in contributing to the scheme, but he needs members of the government, banks, universities, manufacturers and other stakeholders to back it as well. He can see it now though: there could be a unit for knits, another for wovens—perhaps even a transportation company on site. It would have a recycling plant, “so anything that’s waste comes back to us. I want to do circularity.”

“This is a big project,” he said. “It’s not something that will happen, just because we’ve decided to happen. But it would put [the city back] on the map. And it would turn the fortunes around of this industry.”

‘Leicester clothes the world’

Adam Clarke, Leicester’s deputy city mayor, wants to put some “flesh on the bones” of Khan’s plan. But the council is also trying to drum up national support for a so-called “garment trade adjudicator,” a single enforcement body for clothing manufacturing that can “sort out” the problem of weak regulation and even poorer oversight regarding workers’ rights in the industry. This is something that needs to be addressed before “all the eco-parks,” he said.

Clarke said that one question he and the mayor keep asking is what Leicester’s garment supply chain truly looks like—how many people are involved, what elements of the sector are being represented and, critically, where the biggest issues lie. “The fact is there is very little data on that,” he said. Councils also have no authority to enter factories, instead relying on an “alphabetti-spaghetti” of agencies with various powers. Hence the need for an adjudicator like the food sector has.

He believes that clothing production still has a future in Leicester, calling the city a “sleeping giant” or perhaps a “suppressed giant” for quality, quick-to-market manufacturing. Shaking it out of its slumber would require a cultural shift not only within the industry at large but also in the minds of its customers.

“It’s our heritage,” Clarke said. “Leicester wouldn’t be a city without it. Leicester wants to be at the top in terms of reputation. Unfortunately, retailers, because cash is king, end up going for a race to the bottom, which can leave places like Leicester and ethical manufacturers out.”

Labour Behind the Label has taken its complaint to the top: Prime Minister Rishi Sunak. Following the first BBC Panorama report, the organization wrote to the premier denouncing the “continued use of unfair purchasing practices drives illegal employment practices.”

“We previously welcomed this government’s steps to address the working conditions of the U.K.’s most vulnerable workers including discussions around revising the Modern Slavery Act, the Taylor review on modern working practices, and the creation of a Single enforcement body,” wrote Muller in a letter dated Nov. 7 and co-signed by the likes of Anti-Slavery International, the Clean Clothes Campaign and the Environmental Justice Foundation. “It is clear, however, that much more effective and proactive action needs to be taken, especially given the lack of progress made.

It’s difficult to tell how many garment workers are still employed in Leicester. A statistic from 2020 suggests there are 10,000, but this was when there were still 700 factories running at full throttle. Issufo said that the number is probably closer to 2,500, since many have lost or are in the process of losing their jobs. Even those who haven’t been axed are seeing their hours drastically cut, say from 45-50 hours a week to less than 20. For the women who make up a large proportion of the workforce, this has caused “issues in their families and income,” she said. “I have had women coming up to me to say that they’re constantly fighting with their husbands because there’s a lot of pressure to find work. One person cannot afford to pay for everything.”

Men struggle, too, of course, but it’s also easier for them to pick up work elsewhere. Most of the women hail from conservative religious or cultural backgrounds, yoked with childcare, eldercare and other responsibilities that prevent them from traveling to factories that are further away from where they need to be.

“Also their husbands wouldn’t allow them to travel so far or with other men by sharing cars [because] a lot of them don’t drive, so that’s also a barrier,” Issufo said. If Boohoo relocates its Thurmaston Lane staff, not everyone may be able to accept a different posting.

In early October, 500 workers swarmed Leicester’s Spinney Hill Park to protest the unfairness of the industry. Most of them had been reticent about speaking out, according to Labour Behind the Label, which organized the event. At the same time, they felt like they didn’t have a choice. They wanted factories to stay open and keep busy and for brands to take responsibility and commit to orders in Leicester.

One of the demonstrators was Parimjit Kaur, a middle-aged woman who moved to the United Kingdom from Punjab in India eight years ago to join her husband, who had been in Leicester for close to three decades but had been fired because of his bad back and dizzy spells. When Kaur spoke to a journalist through Issufo in October, she had been without a job for two months. Her story is a typical one: It only took Kaur a week to learn how to use a sewing machine and get to work. She came to Britain for what she described as the “good life,” but before she knew it, she was earning less than $4 an hour toiling in dingy, poorly ventilated surroundings where mold and mouse droppings were a common sight and verbal abuse from supervisors a regular occurrence.

“Everyone accepts it,” Kaur said. “If you don’t, you are shown the door.” She was front and center at the protest, Kaur said, to “fight for the next generation.”

Giving the workers a voice

For the past two years, Tarek Islam, a youth worker at Highfields Center has been helping Leicester’s garment workers understand their rights and, to the best of his ability, address their grievances. His official title is senior community engagement and outreach worker at the Fashion-workers Advice Bureau Leicester—FAB-L, for short. Funded by the trade unions GMB and Union and brands like Asos, Boohoo, Next and River Island, it was meant to be if not the answer to the Boohoo scandal, one of the solutions. It’s this hat that Islam wears three days a week at the community center.

There’s a personal stake in Islam’s work; both his parents were garment workers. And the way he sees it, one way to improve conditions in Leicester is for buyers to increase the number of orders and improve their purchasing practices. Boohoo may get a lot of flak, Islam said, but it’s also the only U.K. brand that is manufacturing in the city to a significant degree.

“All those companies not sourcing in the U.K., they’re the ones that need the heat,” he said, nursing a cup of strong Yorkshire tea. “Boohoo took a lot of battering—and rightfully so. But who’s better? Would the garment workers rather have Boohoo operating in the U.K. with exploitative practices? Or would they have rather have Primark, Sainsbury’s and Asda sourcing from Bangladesh? Who’s right and who’s wrong? And who gets to decide that?”

A better industry is possible, Islam believes. He recalled a conversation with a retired garment worker who was employed in the ‘70s and ‘80s. “He goes, ‘Look, it is possible for the industry to change because we used to get better pay than government jobs,’” Islam said. “He said it used to be a respectful job. Clothing made in the U.K. used to be known for quality and ethics. And now it’s obviously turned around.“

So what changed?

“To answer in layman’s terms, I would reckon ultimately it’s the rich getting greedy and they wanted more profit,” Islam said. “I’d say it’s the government that’s to blame as well. It’s strange to say but large corporate companies, they hardly pay any taxes, when we people living in the UK, and small businesses are paying way more taxes than them. Doesn’t make sense. But who’s making that O.K.? The government.”

Islam isn’t just a good listener. In FAB-L’s first year, the group helped workers recover more than $170,000 in missing or unpaid wages. This wouldn’t have been possible without the help of the funding brands, which have allowed the organization access to their suppliers and, more importantly, those suppliers’ workers.

“We won’t deal with problems in the factory,” Islam said. “It’s about making a connection with [workers], building rapport with them, [so they feel free to] contact us afterward in a safe place where they can speak to us openly if they want to raise the issue. We will maintain that we are not a factory police. We’re not an enforcement body. Our job is to give workers a voice—a voice that they have not had in the past 20 to 35 years.”

The last time garment workers spilled into the streets, he said, was in the ‘70s, when the factories’ then-predominantly white owners gave their white employees raises but not their Black or Asian ones. Even the unions refused to represent them, forcing them to organize themselves.

“Since then, there’s been a massive gap caused by the mistrust at that time,” Islam said of Leicester’s low union membership today. “They felt betrayed by the unions.”

The membership rate is something he’s trying to rectify so workers can gain more leverage, especially in factories that are not covered by the funding brands—or any recognizable label—and are therefore less susceptible to being held to account. But the attrition in the workforce has made this an uphill slog. Unions can’t represent workers if they’re not technically working.

FAB-L has started English classes on Thursdays and Saturdays because Islam believes that workers will be less exploitable if they can understand the language. There is childcare help, snacks and, of course, piping cups of tea. Most of all, the group provides a “safe space” for the disenfranchised to gain a sense of belonging through community building. “Basically, garment workers have been made to feel like they’re worthless,” he said.

Above and beyond

On a recent call, Khan was mulling over Boohoo’s announcement about Thurmaston Lane. The Apparel & Textile Manufacturers Federation and the city council are trying to figure some things out, though details are still scant.

What Khan is certain about, however, is that Leicester’s manufacturing future lies beyond cheap, low-quality clothing. It’s not sustainable and fast-fashion brands are not able or willing to pay suppliers and workers what they deserve.

One rumor circulating in Leicester is that Shein is eyeing Boohoo, which neither company has confirmed or denied. It might be a stretch but stranger things have happened. Frasers Group, which owns Sports Direct, Flannels, House of Fraser and, until recently, Missguided, has been snapping up Boohoo shares, culminating in a 21.5 percent ownership on Thursday that’s second only to Kane and the Kamani family’s. Shein acquired Missguided’s intellectual property and trademarks from Frasers Group in October.

Shein products zipping off Leicester’s production lines might be the last thing the city needs, however.

“We need to look at quality, innovation in terms of productivity and also new things like sustainability and recycling,” Khan said. “There are new points of interest that we should be looking at.”

Rising on the north side of Leicester, next to the River Soar, gleams a “pillow”-clad steel building that resembles a wadded-up puffer jacket. This is the National Space Centre, a two-decade-old museum that is also home to the United Kingdom’s largest planetarium. It has become one of the city’s most iconic landmarks, a visible indicator of Leicester’s foothold on space research and engineering. Space has a storied history in the area, if not as storied as garment manufacturing. The first Leicester-built instrument jetted into space aboard a Skylark rocket in 1961. Since 1967, at least one has made it into the cosmic expanse every year.

“We’ve had a huge amount of transformation here,” Khan said. “We’ve renamed this ‘Space City.’ It’s a premier European destination for space.”

He understands the need for Leicester to pivot. Anywhere that wants to survive—business, industry or city—has to continue to evolve. But what about the people who are unlikely to become space engineers?

“The only problem is we also have a large population that is unskilled or semi-skilled and English is not their first language,” he said. “So how do you accommodate those people? The way to accommodate them is to scale them up so they are least able to utilize the skills and the technology that’s relevant to them and their experience in the textile sector.”

That day in October was foggy. From a distance, the National Space Centre looked like a shapeless blob.

“As they say, in English, horses for courses,” Khan said.