Legendary Author Tim O'Brien Is Conscious of His Mortality—and It's Motivating Him in Fatherhood

Tim O’Brien was past 60 when his son Timmy appeared in the living room in the middle of the night crying about his father’s eventual death.

“Timmy was nine, something like that,” O’Brien said on the phone from his home in Austin. “It was one in the morning and I was reading, and he comes in bawling. I said, ‘What’s wrong?’ And he said, ‘You’re going to die and I’m not going to have a dad.’ He could see how old I was, how deaf I’m getting, the gray hair, all the other infirmities that come when you get old. For a second, I didn’t know what the fuck to do. Should I lie? Or pooh-pooh it? But then I could give him the sense that ‘Dad’s telling me that my fears are not real, not earned by the circumstances.’ ”

Fear of death is all over O’Brien’s most well-known novels: Going After Cacciato, which won the 1979 National Book Award, and The Things They Carried, which installed him in the pantheon not just of war writers but all of American literature. (Much of the latter first appeared in Esquire.) Birth is a death sentence—that’s how O’Brien puts it, a variation on Samuel Beckett’s “birth was the death of me.”

But there he was in the living room at 1 A.M. grappling with mortality with a sobbing 9-year-old.

“It was a hard moment,” says O’Brien, who is now 73. “But I said, ‘I know. We’ll love each other while we’re together.’ It’s sad but I said, ‘It’s all right. We’ll get through this.’”

Then O’Brien told Timmy, “I love you,” words he can’t remember his father ever saying to him.

In his writing about the Vietnam War, death is a tormenter, haunting men in horrific, dizzying fever dreams. But in a recent book, Dad’s Maybe Book, and a new documentary, The War and Peace of Tim O’Brien, O’Brien’s fear seems to have evolved into something like acceptance.

Maybe even peace.

As a teenager, O’Brien hid all the sharp kitchen knives under his mattress, convinced that his father was going to kill him. As a soldier in Vietnam he stepped lightly, terrified that he’d step on a land mine that would turn him and his squad into red mist. And when he became a father for the first time at the age of 56, O’Brien, an incorrigible smoker, feared that he would not live long enough to see his two sons graduate from college.

O’Brien’s acquaintance with the fragility of life moved him to write Dad’s Maybe Book, his first book since 2002 and the only one he has written since becoming a father. It’s a collection of essays for his sons—about his life and the lessons he has learned about war and writing—a memento for them when he’s gone.

“They’ll have some—I don’t know what the word is—some sound of my voice to remind them of the man they knew for a little while.”

The specter of death gives the book urgency, but so does the immediacy of life. “You come to value things that never before had such crushing value,” O’Brien writes. “While I certainly do not enjoy old age any more than I enjoyed war, I do feel an intense, almost electric awareness of the physical world, as if everything on the planet has been magnified and brilliantly lighted. When you’re almost dead, things sparkle. What is taken for granted in peacetime, as in youth, suddenly becomes so precious it makes you cry, and if there is any redeeming virtue to growing old, it is the pleasure I take in what had once seemed ridiculously ordinary.”

That quality is lovingly captured in the thoughtful and intimate documentary, directed by Aaron Matthews, which shows O’Brien struggling to finish his last book as he appreciates family life. The filmmaker spent four years dropping in on the O’Brien family—Tim, his indomitable wife Meredith, and their two smart and sensitive teenage sons, Timmy and Tad. We see O’Brien reviewing Tad’s homework and getting whacked around by Timmy in ping-pong. We see him run into the wall of Timmy’s rational, level-headed argument for more screen time. We see O’Brien fumble with his credit card at the gas station and the unintential comedy of dealing with a customer-service agent when his car breaks down—he is a long, long way from Vietnam.

Not only does O’Brien have no memory of his father telling him he loved him, he doesn’t recall his dad ever even telling him he was proud—even after O’Brien won the National Book Award. What he does remember is his father at the ceremony, falling down drunk.

To this day, with his father long dead, O’Brien yearns for a connection with his old man. That’s partly why he decided to write Dad’s Maybe Book and why he agreed to be filmed for Matthews’ documentary. It takes the place of the treasure his father didn’t leave him.

O’Brien never expected he’d be a dad, but Meredith, a classically trained actress and playwright twenty years his junior, threatened to end the relationship if they didn’t have children. In the documentary, Meredith says, “He would tell me, ‘I don’t understand how you can love the concept of something more than you love me.’ But I would say it’s the best thing that’s ever happened to him.”

O’Brien agrees and says to his boys, “I would trade every syllable of my life’s work for five more years with you.”

For him, words, sentences, paragraphs, chapters, books come a drop at a time. He’s the kind of writer who is at it, ass in the chair, 12 or 14 hours a day when he’s working. He does not take weekends, birthdays, anniversaries, or holidays off.

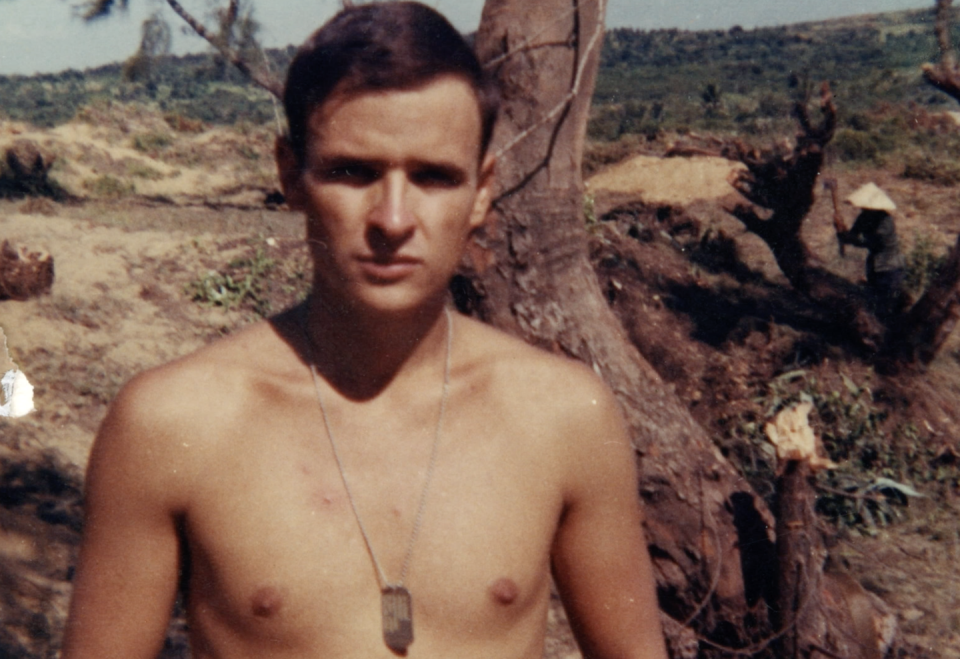

“I am in love with his passion and his talent and his dedication to writing,” Meredith wrote in an email. But she would have loved him even if he weren’t a writer. “He was so handsome,” she said, and a video clip of him fit, muscular and vibrant in their early years bears her out.

It was Meredith who encouraged and pushed O’Brien to leave behind a record for the boys. “An artist makes art, a writer should write,” Meredith says in the documentary. And so, with the boys entering adolescence, their dad went back to work on what he figured would be his final book, wanting to say everything he had to say.

“Those years of silence were in no way a sacrifice,” O’Brien told me. “I didn’t miss writing. And if I had been writing I would have missed so much beautiful, miraculous and exciting stuff. So there was no sense of sacrifice.” Even though his keyboard remained silent, O’Brien supported his family by touring the country, well-compensated to talk about the writing life and inevitably, war.

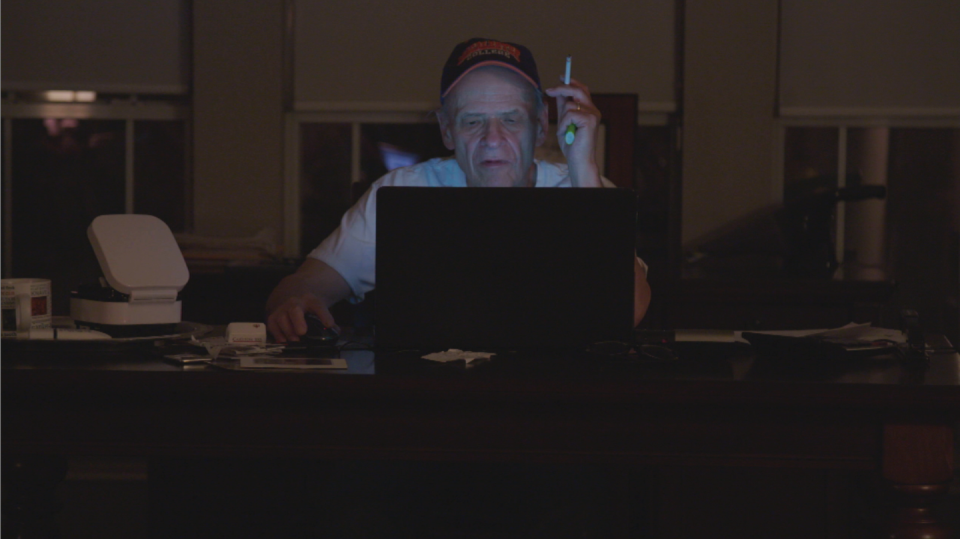

Living through it was hell and writing about it was hell of a different sort. He worked nights, dragging himself out of bed at one or two A.M., the time when the bumblebees of his subconscious were making connections, remembering things long forgotten. And he kept at it until the boys got up at seven and it was time to take them to school. He’d sleep during the day and be awake when they returned home from school, always telling himself his schedule wasn’t a distraction.

Tad is philosophical: “It’s part of life, you know. Some days are better than other days. One day you spill some coffee on your hand and you’re like, Oh, dammit! and another day you just, like, win the lottery.”

His brother Timmy is more pragmatic: “His mood depends a lot on whether he has good or bad writing days. If he has a bad one, it’s gonna be rough.”

There might not be yelling or screaming, but the tension is unmistakable. O’Brien remains tormented by the war. We see him in the middle of the night disinfecting the kitchen floor—preoccupied with how futile his words have been against all the wars being fought—or pretending his bed is surrounded by enemies intent on sneaking up on him.

Two years ago, O’Brien was hospitalized with pneumonia. It was maybe the fourth or fifth time in his life he’s had a case so severe. He began to hallucinate, sure that hamburgers were being ordered from a body shop and delivered to his house by a booby-trapped conveyer belt, the trays upside down on the bottom of the conveyer belt.

As he got sicker, O’Brien was conscious of his mortality in a way that reminded him of Vietnam. “Maybe that’s how biology prepares us for death,” he told me. “Before you lose reality and die and leave this real world, you’re sort of prepared for it.” He laughed. “But then, you even lose awareness of mortality. It doesn’t exist anymore. You’re not worried about dying when you’re dying—you don’t know what dying is.”

It took weeks for him to snap out of this dream state when he returned home from the hospital. He asked Meredith what he’d been like. She told him that one day Timmy went to use his dad’s computer and saw in the search history that he had been researching insanity. Timmy wept and told her, “Dad knows he’s insane.”

Turned out O’Brien looked up insanity before he got sick for a chapter he was writing in his book about Ernest Hemingway.

“It broke my heart,” O’Brien told me, “that my kid was aware that his father was nuts, and I was. I believed things that were not true with a ferocious stubbornness. To have two young kids living with a man who has really gone out of his mind because of the pneumonia, that was just heartbreaking.”

Tim’s going to die. It’s something Meredith thinks about often, even more now since COVID. Yet we see here in the documentary at the gym, a strong, powerful woman, lifting weights, determined to be healthy for herself and her sons. “My mother dropped dead at 52 of a heart attack,” she told me. “So the idea of mortality is not something I’m in denial about.”

The pneumonia was a frightening episode. O’Brien looks borderline cadaverous, his previously toned physique now hidden underneath loose-fitting T-shirts,. He’s rarely without a cigarette, even on his way into a health clinic.

“I knew what I was getting into marrying a smoker,” Meredith said. “Tim hates it, I hate it, the boys hate it. When they were little, sometimes their preschool teachers would tell me they could smell cigarettes on their clothing and nap blankets. I mention quitting to him about once a month, even more these past couple of months, and it never turns out well. But I have not made peace with his smoking. I never will. I pray every day he will stop.”

So does her husband. “I try hard not to smoke around the kids, but I do smoke. Still. It’s my equivalent of my dad drinking vodka—it’s chemistry. If it doesn’t kill me it’s certainly not going to keep me alive any longer.”

In the documentary O’Brien says that when he stopped writing to have children, “I made a resolution to be a decent father.” The word decent is revealing because we see O’Brien unable to shake his quotidian pursuit of perfection not just in his sentences but when he’s bowling or performing magic—a longtime obsession at which he is more than adept. “Decent” is a humble word, the opposite of perfection. It connotes showing up, even when things are complicated and painful.

When words fail.

“Just be there,” he told me. “Go to the dinner table and be with your family. It helps me and I think it helps them, too. It’s not a pleasant time when things go badly but it’s not pleasant if you’re a surgeon and you botch a surgery and kill somebody. We all have downs in our life, and I don’t think mine are more severe than anybody else’s. It would be an act of hubris to say otherwise.”

O’Brien laughs. “Novelists in particular sometimes think theirs is some special suffering.”

Official Trailer - The War and Peace of Tim O'Brien pic.twitter.com/pGoIDebXzD

— Tim O'Brien Documentary (@timobrienfilm) May 14, 2020

O’Brien felt relief when Dad’s Maybe Book was done. But a writer writes, as Meredith says, and soon he began to miss those wee morning hours alone with the bumblebees.

“What’s bizarre,” he says now, “is how it’s coincided with this other kind of isolation that’s going on in the world now. The quarantine stuff. It’s as if I’ve left one strange world and joined an even stranger world.” He laughs again. “Now, I’ve got the whole world as company, knowing how I used to live.”

In The War and Peace of Tim O’Brien we witness a sliver of the time he has left with his sons and his wife. If not for the untimely COVID interruption, the documentary would be making the festival circuit right now in hopes of finding a landing spot at Netflix, Prime, Hulu, or American Masters or some such prestige spot. It deserves an appreciative home because among its many virtues is its length: a tidy hour and 24 minutes. Matthews is a disciplined storyteller, uninterested in self-indulgence.

The effect is that, as you watch the movie, you find yourself—as O’Brien does—dwelling on the time we have left and how to use it.

Maybe Timmy and Tad will one day want to know more about their dad’s war stories, and perhaps Dad’s Maybe Book will provide some answers to their questions. They’ll have the documentary. They lived through their dad writing this book for them, saw how many hours he spent trying to get everything right. They know about hard work and rigor as an expression of love, and they will know how much their father and mother loved them, and maybe that will make them less afraid.

You Might Also Like