I Left Dancing for Food…And Found Love Along the Way

This essay is an excerpt from Everything Is Under Control, a memoir with recipes by Phyllis Grant. It contains references to eating disorders and sexual abuse.

We are so hungry.

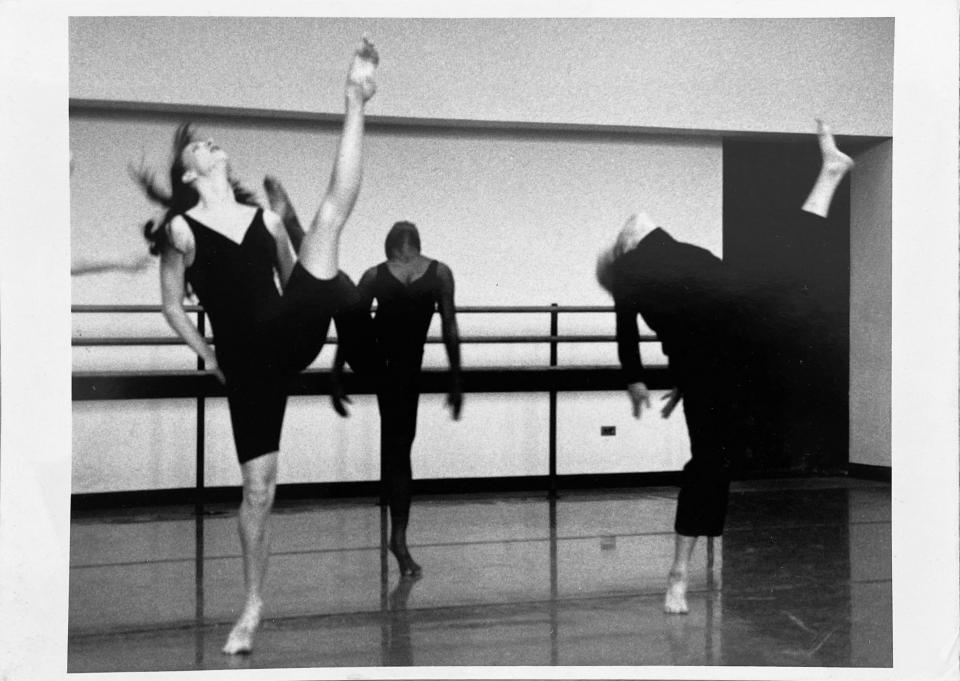

We dance all day long. In the studios. In the stairwells. On the sofas in the lounge. Down Broadway. It is my childhood dream come to life. The New York City package: 1988 style. Dance school. Depressing apartment. Leg warmers. Straw basket bag like Coco on Fame.

There are no dorms. We don’t know how to cook. New York City is our cafeteria.

White onion, cheddar, and tomato omelets with French fries in fluorescent diners, all-you-can-eat barbecue ribs at Dallas BBQ , General Tso’s chicken with free white wine, Ben & Jerry’s New York Super Fudge Chunk ice cream, banana muffins with inch-thick streusel, airy blueberry scones, Häagen-Dazs bars, Doritos, and Peanut M&M’s.

We don’t care what we eat. We just want to be full so we can do it all again the next day.

hea-phyllisgrant-dancing.jpg

****** My nightly soundtrack is made up of car alarms, a hissing radiator, and the frantic inhales and exhales of my assigned roommate trying to climb the walls. Several times a week, she puts in a James Taylor tape and run run run slams her naked body against the wall, her hands and feet clawing at the chipped paint, sobbing as her body slides to the ground.

I meet her older brother. He has scars over a quarter of his body. Something about a backyard barbecue and an exploding can of lighter fluid and the death of an older sister. He asks me to watch out for his baby sister.

She tiptoes down the street as if she is walking on air, smiling hard at everyone, engaging strangers in conversations about the beautiful day, her light blue eyes brimming with tears, her ecstatic bliss changing midsentence to deep gloom.

She buys a folding shopping cart at Bed Bath & Beyond that she pushes up and down Broadway. She bursts through the door with a new collection of gathered items: a broken lamp, three packages of stale Mint Milanos for the price of one, a man she met at Tasti D-Lite frozen yogurt shop.

I shake her awake every day. I feed her granola. I tuck the hair behind her ears.

****** My ballet teacher squeezes my waist. He trained with Rudolf Nureyev and wears a cape that he flips back when he’s angry. He smacks my ass with a stick.

Stop eating so many croissants, Phyllis.

He says I have an attitude problem. He would like me to disappear.

We share a bathroom with the School of American Ballet, I listen to the heaving in the stalls. I watch girls erase their femininity, their fertility.

I learn the tricks.

A stick of Juicy Fruit gum is ten calories and if you chew it for over an hour, you will burn eleven calories.

Bulimia is much harder to cover up. It’s loud and messy. But you get to eat more. Anorexia is clean and requires control.

I choose anorexia.

Breakfast is coffee and a cigarette. Lunch is a cigarette. Dinner is broth.

I think I’m in control. I hear the words I want to hear: You look great, Phyllis. Look at the line in your penché. You finally have a waist.

I audition for the big performance at the Juilliard Theater. I don’t even get cast as an understudy. I almost get cut in my first evaluation. So I ask why.

We saw a lot of potential in you but you haven’t lived up to it. Your technique is very weak and we’re not sure you’re going to make it here at Juilliard.

I go to the Juilliard Halloween party. Alcohol hits my empty stomach. I don’t remember getting carried out of the school and ten blocks up Broadway to my apartment. I don’t remember how I get out of the tight green dress. I do remember waking up as my head slams the side of the bathtub, my body slumping to the tile floor.

****** Head down, purse pulled into body, face emotionally sealed, I move with the anonymous throngs up and down Broadway. I find a speed I never knew I had. I walk for distraction. I walk to try to understand what to do. I walk to try to figure out who I am. I am eighteen.

I visit every church, temple, mosque on the Upper West Side that will let me in. I breathe in the religious air. It feels thick, cool, supportive. It smells musty but sweet like my grandmother Elizabeth’s garage. I pretend to believe in God by listening to the music, planting my feet on the cement floor, holding a Bible to my chest.

I peer into brownstones. I want to sit at those kitchen tables. I want to be fed. I buy a box of cake mix and make it in my microwave. To watch it rise. For the smell. To feel the warmth of just-baked anything in my hands.

****** Why don’t you take your clothes off, Phyllis. Yes. Like that. Nice. And now do the splits. Beautiful. Let me photograph you from the other side. Hold on. Wow. I am so grateful to you. These photos will be so helpful. Now cup your breasts. Yes. That’s it. Yes.

I am not the only Juilliard dancer who goes downtown to the Puck Building to have her picture taken in the anatomy teacher’s special studio for his extracurricular project. None of us tell. We don’t want to ruin his life.

****** My mother sends me newspaper clippings. Where to get the best tea. Lists of the best New York City restaurants. Farmers’ market locations. Thanksgiving hotline numbers. Turkey cooking tips are highlighted: You need half a cup of stuffing for each pound of bird. Safety tips are circled: Thyme has been shown to be active against salmonella. How I need to check my turkey after two and a quarter hours. How much she will miss me at Thanksgiving this year. How my brother is growing an inch a week. How much she loves me.

But my first Thanksgiving away from home isn’t in a home kitchen. It is a prix fixe dinner at Windows on the World at the top of One World Trade Center. Three young women. Three bottles of wine. Three courses consisting of gelatinous corn chowder, dry turkey with mucousy gravy, leaden apple pie. Two out of the three of us throw it all up in the fancy bathroom. Before we leave, I stand at the floor-to-ceiling windows, tracing the avenue lights straight back uptown to my new home. Here, 100 blocks south and 107 floors up, I am relieved to be so far away from it all.

****** I’m fine, Daddy. Everything is fine. I love you too.

I hang up the pay phone outside my apartment building, step over a homeless man, walk past the bullet hole in the lobby door, and take the stairs. A few flights up, I sit down. The stairwell stinks of piss and misery. The building around me vibrates with Bach, Madonna, and laughter.

I don’t want what I thought I wanted. I don’t want to decide what to eat. I don’t want to be set free.

I light a cigarette and inhale menthol smoke as often and as deeply as one cigarette will allow, all for that two-second dopamine buzz that makes space in my brain for the belief that life won’t always feel like this.

I am a very good dancer. But I will never be a great one.

All I want is to go home and eat my mom’s roast chicken.

****** It’s small. It’s filled with roaches. It’s coated with the stink and stickiness of the previous ten tenants. But it’s mine. My first kitchen. With a gas stovetop and an oven with a broiler drawer. The freezer has a two-inch border of ice but it’s big enough for two pints of ice cream for my new roommate and me. I have a place to collect condiments. I buy a dish towel and an apron. I open my mom’s recipe book and follow her cursive through the chopping of the onion, the toasting of the rice, the never ever lifting of the lid until the timer goes off. I end up with a pot of brown rice. Her words work.

****** An actor or a stockbroker or a film director sits across from me at a diner or a bar or on a park bench reciting his overused script of it’s so nice to be out with a beautiful girl, you are so different, so special, so cultured. And off we go to watch a foreign film or see an art exhibit at the Whitney or visit his favorite drama bookstore. We end up back at his teeny tiny apartment or black marble penthouse or West Side brownstone where we roll around and talk and roll around and talk, pressing body parts to body parts because sometimes that’s enough. And then he reminds me of who is hanging over us: the beautiful homecoming queen or aspiring model who never ventures uptown or fiancée back in Charlotte. He says I can’t, I can’t, I can’t, I really shouldn’t until bam he lets go and says she would probably be fine with us having sex because she is a very open girl and in that moment I get mature and moral beyond my eighteen years and say this is not right, let’s just fall asleep and see how we feel in the morning. I leave before he wakes up and do the walk of shame through Lincoln Center with my smeared mascara and the previous night’s carefully chosen dress, feeling like the best person in the world because I’ve saved his relationship. I power through the forty blocks home with my light coffee and a slow-building regret: why didn’t I just sleep with him because at least I’d have that.

****** For my second Thanksgiving away from home, I take the train to Pittsburgh to visit friends at Carnegie Mellon.

The air is bitingly cold. The landscape is bleak. The East Coast just feels fucked up.

But there is a comforting sameness to our failed romantic entanglements, our lack of focus, our existential angst. We have taken a few too many steps outside our comfortable worlds and we’re all ready to run back home to California.

Their apartment is huge, two floors perched above a pizza parlor. The kitchen is large enough to comfortably accommodate our dysfunctional group. We fumble our way through planning our first Thanksgiving dinner. Even though I have never done this before, I find myself in charge.

Before bed, I tear up the challah so that it gets stale for the next day’s stuffing. I study the map of recipes written by my mom. My entire childhood Thanksgiving experience is on paper. Mashed potatoes. Mincemeat pie. Creamed onions.

I can’t sleep. I am scared to begin.

I get up early to take the turkey out of the fridge and bring it to room temperature. I dice onions and sauté them with a stick of butter. I add celery and seasonings, the stale bread, and chicken stock. I can hear my parents’ and my grandparents’ voices. More salt. Taste. More liquid.

Taste. More poultry seasoning. That’s it. Now stop. The bread will soften. The turkey juices will flavor the stuffing. Don’t overdo it.

I carefully separate the turkey skin from the flesh, making room for slices of cold butter. I press the stuffing in both ends of the bird, sew it all up with large scrappy stitches, and wrap the string a few extra times around the ends of the drumsticks. Just in case. I don’t want a blowout. And then I tie a knot and hope for the best. It all feels very fragile, intimate.

But I don’t know when it’s done. How long it should rest. How to carve it. What’s safe. What’s dangerous. All the things that aren’t written down on the recipe pages. I call my parents with questions every hour until the turkey is on the kitchen table.

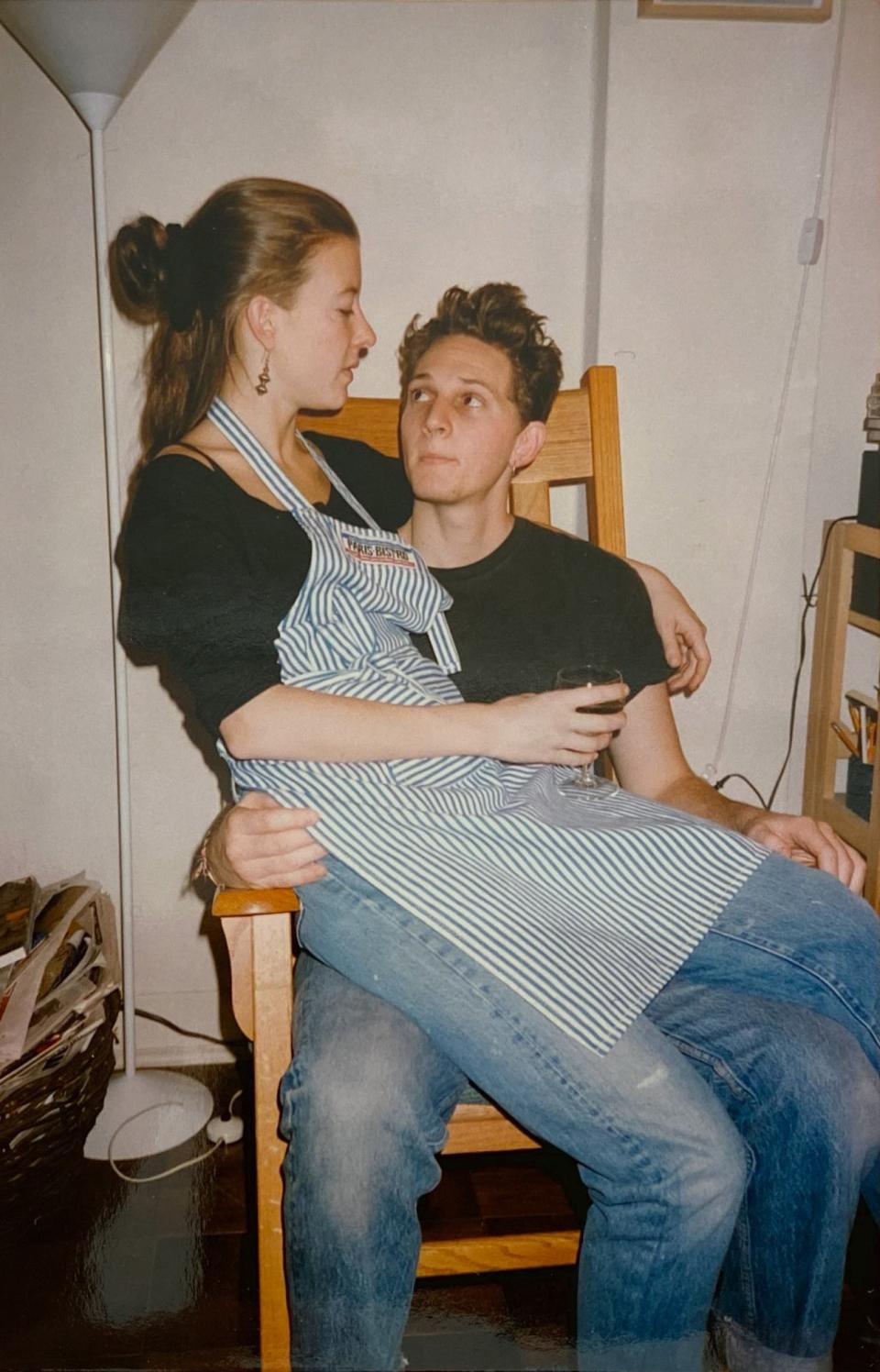

****** He buzzes me in.

I walk up the lopsided stairs, hearing the clanking of dishes from each apartment, smelling three floors of family dinners.

He doesn’t know that I have been crushing on him for weeks, following him around school, getting as close as I can on the stairs, trying to hear what he is listening to on his Walkman, once almost reaching out and touching his shirt.

He is waiting in the open door. I slip past him. I already love his faded Levi’s, his white T-shirt, his smell.

There is no table, no bed. There are no chairs. Just French movie posters on the walls, a futon, a jar of tomato sauce in the kitchenette, a pile of Doc Martens in the corner, a stack of The New York Times that comes up to my knees.

I feel unsteady from the steaming furnace, the tilting floorboards, my racing heart.

We get stoned and watch The Big Blue, a movie with dolphins and deep-sea diving and Rosanna Arquette. Halfway through, he pauses the VCR.

Are you hungry, Phyllis?

I sit on the floor and watch him melt fourteen cloves of finely chopped garlic into olive oil. As he pours the jar of tomato sauce into the hot oil, it splatters up the white high-gloss kitchenette wall. He sets the floor with black plastic place mats and carefully folded cloth napkins.

The snow blows sideways past the windows. We fall asleep back to back, hands to ourselves.

****** Six weeks in and he is shaking.

Phyllis?

I am one large heart.

Matthew?

I get up early before dance class just to experience the in-love version of my morning routine. The sky is bluer. Cheese Danishes taste better. My grands jetés are higher.

****** When we’re not kissing, M and I talk about food.

We walk around the West Village and peek into the French bistros we can’t afford.

We wait in line on the Upper West Side for over an hour to eat apple pancakes, buttermilk waffles with bacon, paprika home fries, and cream biscuits with strawberry butter.

We spend a week’s worth of food money on a dozen ravioli filled with butternut squash and sage. We carefully boil the precious pillows and then drown them in garlicky tomato sauce.

I can’t get through the Juilliard lobby fast enough. I wait for the elevator with musicians, their instruments glued to their bodies.

I throw The New York Times and a pack of Marlboro Lights down on my favorite corner table in the cafeteria and pull out the crisp food section. I don’t want to read it yet because then it will be gone and I’ll have to wait for another week.

I eat the streusel top off my enormous blueberry muffin and sip my light coffee. I look out at the yellow-cab blur at the intersection of Sixty-Sixth and Broadway. The morning light makes me hopeful. I finally let myself open the food section and flip through until I find the latest restaurant review. I read it over and over again.

I head one flight up to the dance studio and start my warm-up. As I demi-plié, demi-plié, grand plié, I am thinking only about grilled monkfish and chocolate soufflés with molten centers.

Originally Appeared on Bon Appétit