Leaving Neverland, review: Michael Jackson 'victims' paint horrifying picture of child abuse

The image is simple, stark and deeply sinister: James Safechuck, 41, places a small gold band, inlaid with diamonds, over the top of his ring finger; it won’t even fit past his first joint. The tiny ring, he says, was given to him by Michael Jackson, as part of their secret mock wedding ceremony, in which they made vows to one another when Jackson was 30 years old, and Safechuck just ten. Hands trembling, he then places the ring back in a box with several others; the late singer would often buy him jewellery, he alleges, as a reward for performing sexual acts upon him.

The gruesome allegations are just two in a barrage of revelations made in British director Dan Reed’s hotly anticipated documentary, Leaving Neverland, which premiered on Friday at the Sundance Film Festival in Park City, Utah. The four-hour, two-part film, to be broadcast in the UK on Channel 4 in March, was always expected to be controversial, exploring the claims of extensive abuse from Safechuck, a former musician, now a computer programmer, and 37 year old choreographer, Wade Robson, both of whom previously testified in court in Jackson’s defence.

The Jackson estate has called the film "yet another lurid production in an outrageous and pathetic attempt to exploit and cash in on Michael Jackson", who died in 2009.

Before the curtain went up, the Sundance audience was told that healthcare professionals were on hand should any of the content prove, in the current parlance, "triggering". Yet few in the audience were truly prepared for the level of graphic detail in the sexual encounters described candidly by both men, which, in Robson’s case allegedly took place from the age of 7, and with Safechuck from ten.

The audience gave Safechuck and Robson a standing ovation at the end of the film, with many of the critics expressing horror at the revelations.

In one particularly horrifying remembrance, Safechuck also takes the audience on a virtual tour of Jackson’s extensive Neverland ranch, north of Santa Barbara - through the model train station, the movie theatre, the "castle", the tee pees and the swimming pool; "We would have sex there," he says, flatly, of each location on the list. "It would happen every day. It sounds sick, but it was like when you are first dating someone - you do a lot of it." The men also allege regular abuse took place during "sleepovers" at Jackson’s other properties, including the "Hideout" in Century City, Los Angeles.

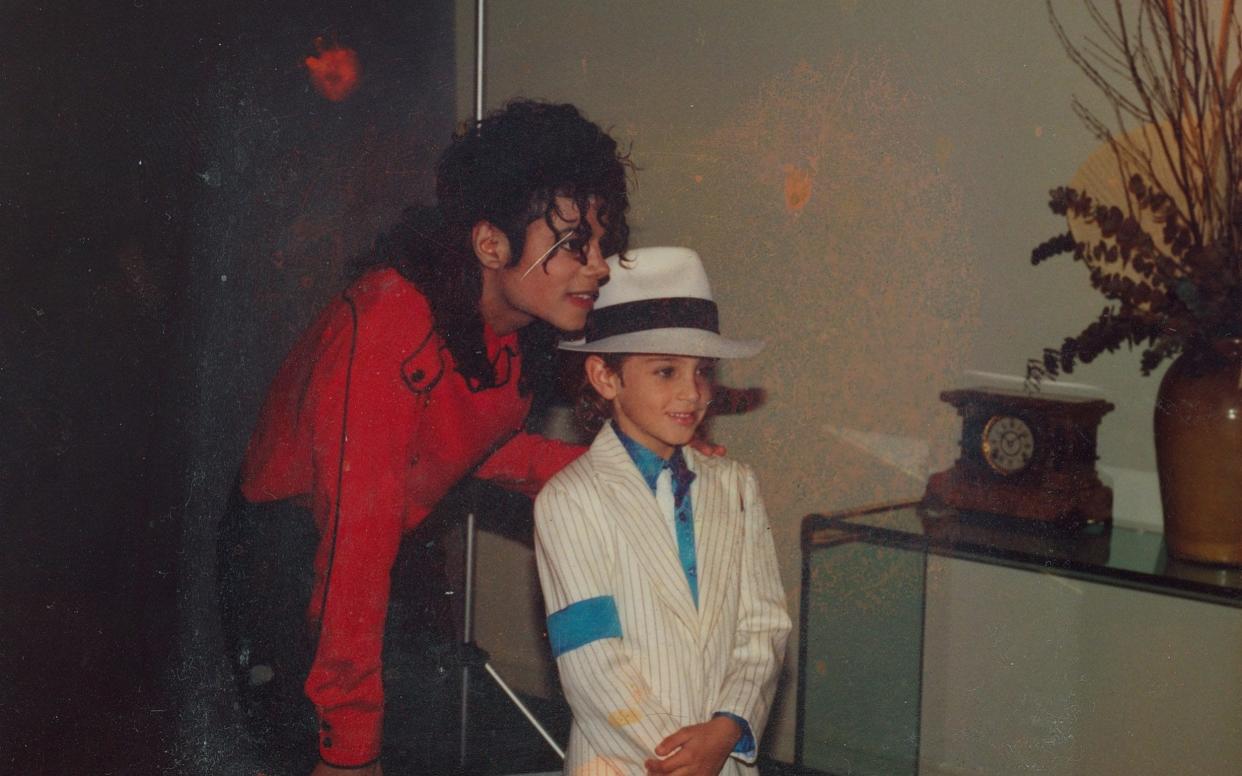

Their intimate and devastating testimonies are convincingly backed up by albums-worth of archive photographs of them, as boys, with the pop icon off-duty and seemingly relaxed, recordings of messages from Jackson, and, in Robson’s case, hundreds of faxes filled with love and affection for the boy he called "Little One".

'Leaving Neverland,' the 4-hour documentary on Michael Jackson's alleged child sexual abuse, is absolutely devastating. #Sundance

— Marlow Stern (@MarlowNYC) January 25, 2019

Michael Jackson doc Leaving Neverland just ended. Absolutely devastating. Q&A about to start.

— Tatiana Siegel (@TatianaSiegel27) January 25, 2019

Reed spent three days interviewing Robson, and two interviewing Safechuck, and the raw, emotional recollections of both men are testament to their trust in the filmmaker. But what elevates Reed’s film beyond simple, lurid headlines are the interviews with both men’s families - Robson’s mother, brother, sister and grandmother, and both of Safechuck’s parents - whose contributions paint a picture of a structured, sophisticated and well-practiced campaign of grooming by Jackson, not only of his alleged young victims, but of their entire families.

While Wade and Robson attest to having been in love with their abuser, both their mothers describe having no idea what was going on when they permitted their young sons to regularly share a bed with the superstar. Their parents and siblings were often staying in close quarters, often even in the next room.

The second part of the documentary focuses on the unravelling of the alleged secret and sordid world Jackson had created, as he faced charges of child molestation, first by Jordan Chandler in 1993 (which was eventually settled out of court for $23,000,000), and in 2005 by Gavin Arvizo (at which Jackson was found not guilty), through to Robson and Safechuck’s own awakening to the alleged abuse they had endured themselves, via breakdowns, bouts of depression and substance abuse.

Reed’s film is entirely sympathetic to Jackson’s alleged victims, and, to a certain extent, to their families, who were beguiled by the singer’s overwhelming star power ("It was one big seduction," says Safechuck), but does not wholly absolve them of their complicity. Safechuck’s mother, Steph, admits as much herself: ‘I f----- up, I failed to protect him," she states.

But there is no ambivalence whatsoever in the film’s decisive and damning verdict on Jackson. Steph Safechuck, again, puts it succinctly: "He was a paedophile’."