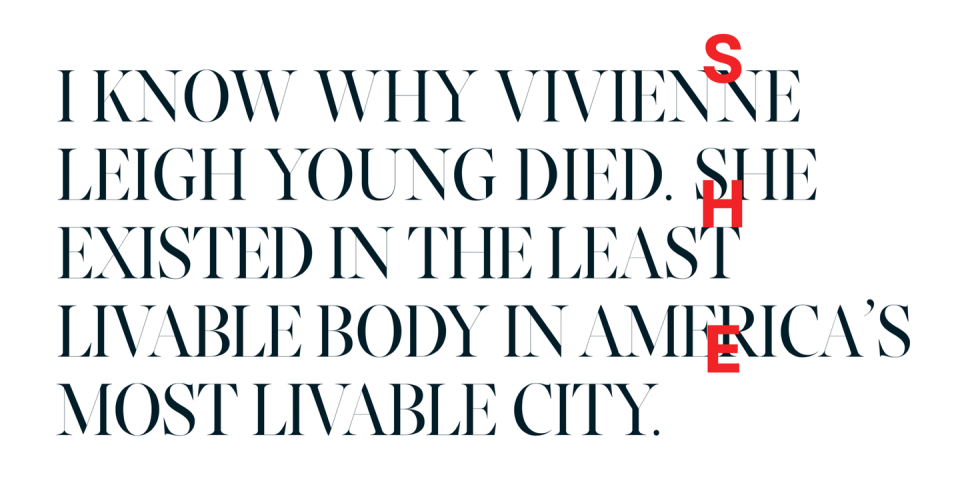

The Least Livable Body in America's Most Livable City

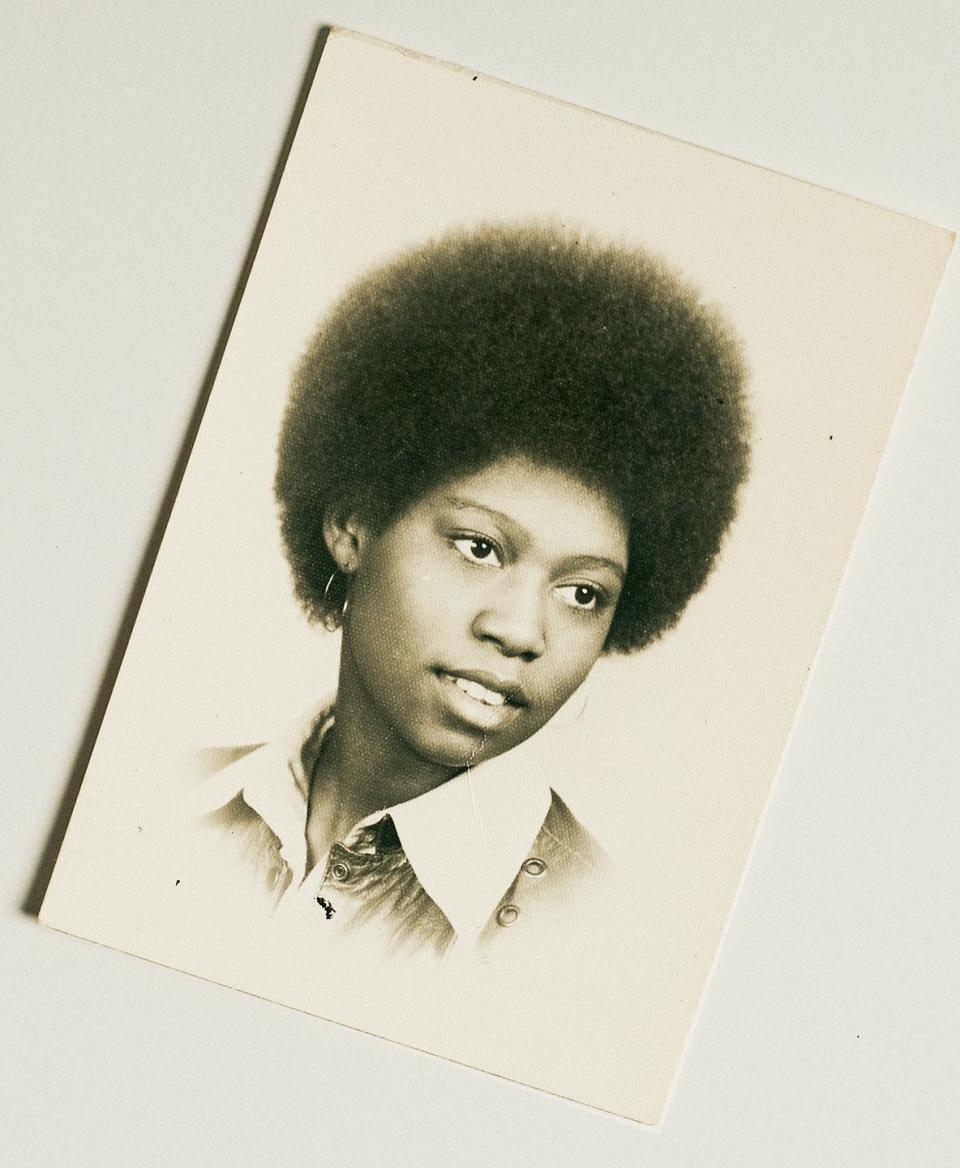

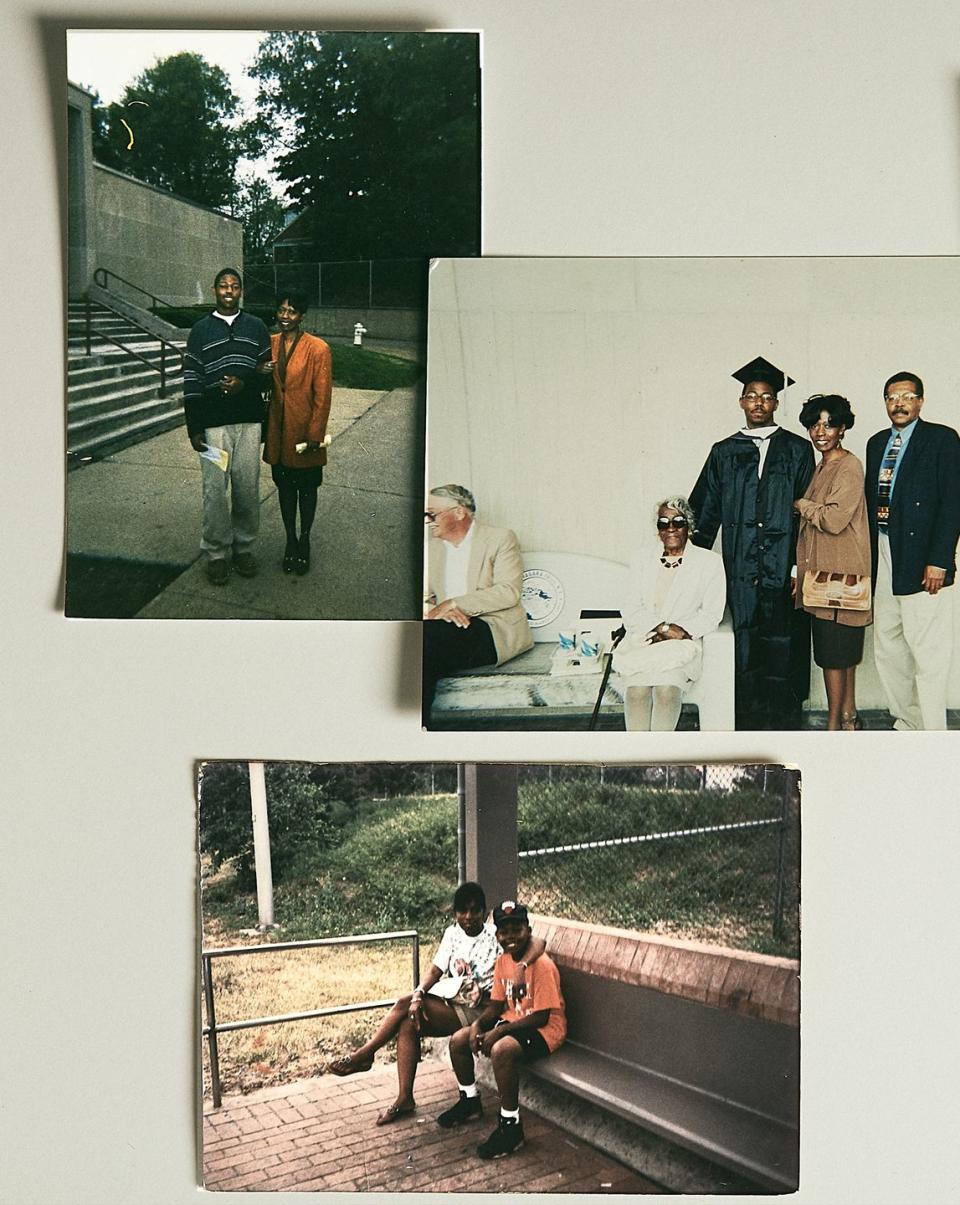

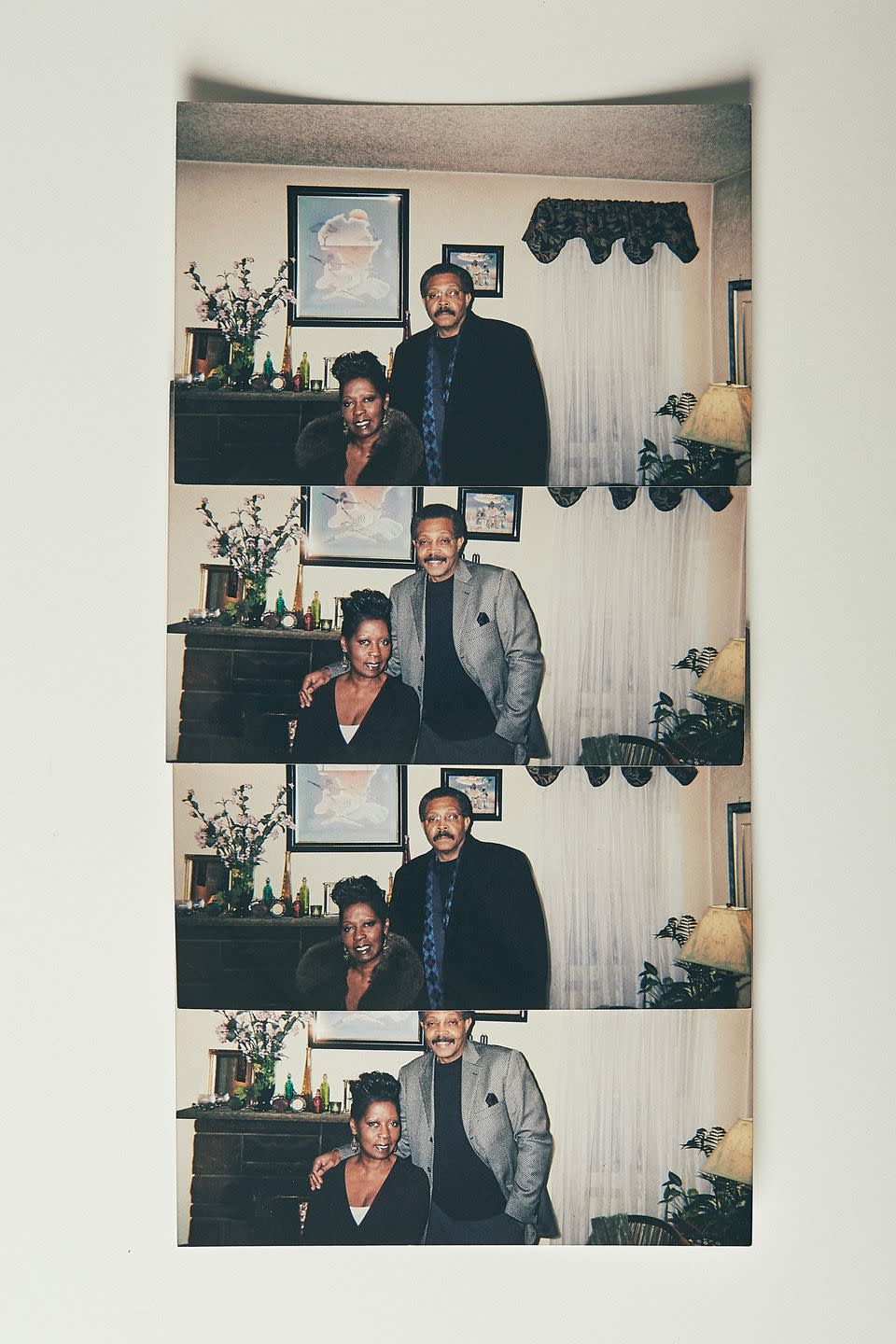

So I'd thought that the last picture of me and Mom before she died, on a hospital bed in the living room of the Penn Hills house my parents were renting after the bank foreclosed on theirs of ten years, was taken in the lobby of Mount Ararat Baptist Church, in Pittsburgh. It was the day I was baptized, in 2013, which my soon-to-be fiancée convinced me to do because we liked the church and it was a requirement for joining. My gray slacks are the bottom half of a Sean John suit I'd bought off a clearance rack. The red gym bag that hangs on my left shoulder contains the soaked white shorts and crewneck I'd worn beneath the white caftan provided by the church for my immersion, in the wading pool behind the altar. I'm smiling, which I rarely do in pictures but always did with Mom because she'd get mad when I didn't. "Why do you look like you're about to sneeze?" she'd say. But in Vivienne Leigh Young's final year on earth, as our family witnessed time—her time—flattening and narrowing and draining and eventually slimming to a whisper, we couldn't afford to waste any more of it with second takes. So I started smiling first.

Mom is smiling, too. The hair she'd lost during chemo had grown back enough by then so that her low Caesar looks intentional. Chic. My right arm is wrapped around her. I remember the shock of that embrace, my hand feeling bones where flesh and healthy fat once were, scared to squeeze too tight for fear of breaking something. I hugged her the way you might hug a Jenga tower.

But on a recent search through my Facebook archives, I realized that I was wrong. The last picture of us was taken two months later. My parents had decided to join Mount Ararat, too, but by then Mom was at a hospice in Lawrenceville, where she'd stay for three weeks before being discharged to spend her final five days on earth at home. Two associate pastors came to the hospice to perform the ceremony. She cried. I recorded it on my iPhone. We took pictures afterward.

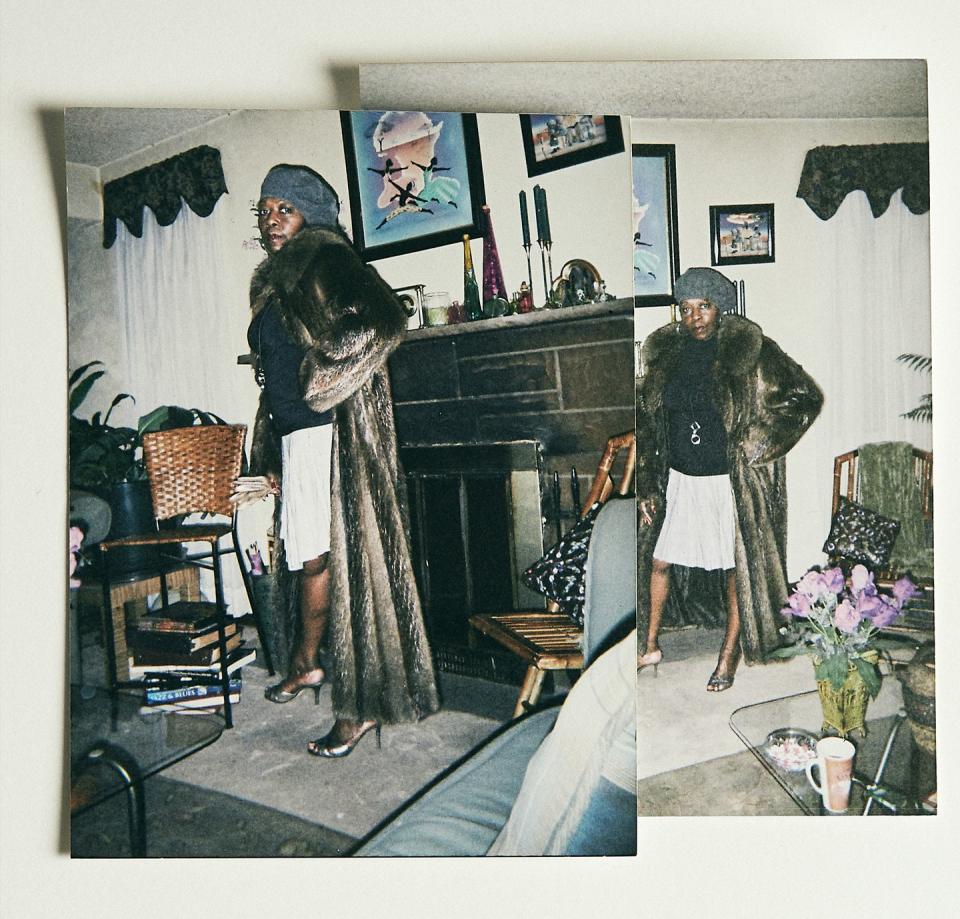

I considered sharing this story at her wake, as a segue to how I'd try to emulate her meticulousness and fearlessness with fashion. Like the time in seventh grade I rocked her bolo ties with my school uniforms while most of the boys at St. Barts wore the clip-ons you'd find at Rite Aid. Which could've then segued to the gray Pittsburgh Saturdays she'd brighten with daylong living-room comedy marathons. Seems Like Old Times before lunch. Defending Your Life at three. High Anxiety after dinner. Or how she was named after Vivien Leigh—my nana's favorite actress—but her name was spelled Vivienne, because she was special.

Instead, I led with a story about her scrambled eggs, how I never liked them because she'd add milk while mixing, and they'd be runny, and I prefer eggs that remain still. And how I couldn't tell her that—not because she was so precious about her food but because my lie had stretched so long. And how I'd pour salt and pepper on them and make bacon-and-egg sandwiches with them. Finally, I confessed. "Sorry, Mom," I smiled from the stage, to the two hundred people in attendance, "but I don't like sandwiches that much."

I think I chose to lead with that story at her wake because I knew the laugh would be easy, and I needed one then to get me through the rest of the speech. The rest of the day. The rest of the week. But the memories of that time, like most seven-year-old memories, are hazy. Even the ones I'm certain I remember exactly as they happened are wrong in some way. But once exposed, the false reminiscences still feel just as real. More true than the truth. Sometimes the feeling a story stirs in your gut is the only thing that matters. Not always. Sometimes.

But it doesn't matter where or when the very last picture of me and Mom was taken. Or what I was wearing. Or how many takes it took. Or why I chose to say what I said at her wake. Such details are gratuitous. The why, though—why Mom died that year, in the living room of the Penn Hills house my parents were renting after the bank foreclosed on theirs of ten years—is what festers.

She spent her last years in pain. A mysterious, excruciating pain—in her back, her stomach, her head. If it seems obvious now, the source of that pain, it wasn't so clear to the doctors she saw at the time, who found no consensus on what was wrong and who advised her to exercise more, drink less pop, drink more water, take a few Advil. Then, a year before she died, a diagnosis: lung cancer. Stage 4. Six months.

This article appears in the October/November 2020 issue of Esquire.

subscribe

The medical care Mom received after her death sentence was good. Which perhaps is how she stretched those six months to twelve. So good that the suspicion I had after her death—that she might still be alive if she'd been treated with as much care when she first started seeking treatment—solidified into a conviction. When she was a terminal cancer patient, that status was her primary identity when receiving care, superseding race, gender, and class. She was considered vulnerable. Defenseless. Worthy. Of protection. Of pain relief. Of treatment. Of effort. But when she was just another Black woman, she was just another Black woman and treated as such. Of course, I have no hard proof of this. Just faith in the consistency and reliability of Pittsburgh's grift. And the belief that Vivienne Leigh Young died—was killed—because of her place in this place.

Finding national lauds for my hometown is like finding a needle—any needle—in a stack of needles. In 2010, Forbes coronated the 'Burgh America's most livable city. A few years later, The Economist declared the same for the continental U. S. "A hidden gem," said the Huffington Post in "What Pittsburgh Can Teach the Rest of the Country About Living Well," which ran two months after Mom died. In 2015, the blog Brooklyn Based asked, with no hint of irony, perspective, or shame, if Pittsburgh was "the next Brooklyn," then took three thousand words to find the answer. ("We think so, maybe?") A 2017 column from The New York Times's Frugal Traveler made the city sound, well, sexy.

There's so much I can say to back up these proclamations. Pittsburgh is a topographical marvel planted in Appalachia. If approaching from the west on I-376, you won't see the skyline until you pass through the Fort Pitt tunnels. Then, ensconced amid mountains and converging rivers, you'll come upon a view so distinct that you'll want to memorialize it as a tattoo—which is what I did on my left biceps two years ago.

The city's livability isn't just an abstraction. I began writing full-time eleven years ago, after getting laid off from the college-prep program I managed. I survived on long-term unemployment and freelance gigs while building my blog (Very Smart Brothas, now a part of The Root) in a way I wouldn't have been able to in Philly or D. C. or New York. My rent for a six-hundred-square-foot apartment in Shadyside, one of the most expensive neighborhoods in the city, was just $590 a month.

Yet this beautiful and bountiful and livable place is, according to "Pittsburgh's Inequality Across Gender and Race"—a report by the city's Gender Equity Commission released in September 2019—"arguably the most unlivable" city in the country for Black women. Black women in Pittsburgh are more likely to die from cancer or cardiovascular disease or a drug overdose or homicide or suicide than Black women virtually anywhere else in the country. And are more likely to have their pregnancies end in fetal death. And are more likely to give birth to underweight babies. And are more likely to live in poverty. And are more likely to be unemployed. And are more likely to have the police called on them in high school. And earn fifty-four cents for every dollar a white man earns. The health disparities are particularly brutal, considering that the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center (UPMC) is the largest nongovernmental employer in the state of Pennsylvania, UPMC Presbyterian Shadyside ranks as one of the best hospitals in the country, and UPMC Children's Hospital ranks as one of the best in the world. There are few better places on earth to be sick than in Pittsburgh. And few worse places in the country to be sick if you're a Black woman.

In response to the commission's findings, the Reverend Ricky Burgess and Robert Daniel Lavelle, Pittsburgh's only two Black city-council members, proposed a bill declaring racism a public-health crisis, which unanimously passed in December 2019. Modeled after legislation passed in Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, the resolution committed the city to equitable hiring practices and diversity initiatives. (Around sixty state and local governments across the U. S. have passed similar bills; this past September, Senator Elizabeth Warren, Representative Ayanna Pressley, and their colleagues introduced a plan to formally declare racism a public-health crisis nationwide.) The 'Burgh's resolution was not legally binding or government funded. Still, it felt like something, something heavy, and like more heavy somethings would follow. Yet almost a year later, nothing's changed.

With all due respect to August Wilson, this is the new Pittsburgh Cycle. Fund and release a study articulating the many ways in which Pittsburgh is uniquely—superlatively—bad for Black people. Deploy a few solemn--faced politicians—some sincere, some performing for attaboys while in line at Pamela's—to regurgitate the findings and pledge to change. Wait for the motherfucking tooth fairy to slip said change under our pillows while we sleep. Then it's report season once again.

Still, none of this sufficiently explains why Pittsburgh is so livable for white people and so unlivable for Black men and Black teens and Black children and Black babies and, specifically, Black women.

The answer can be found between Centre and Bedford avenues, where the Civic Arena, the world's first major sports venue with a retractable roof, was built in 1961. Which is also where, in the mid-fifties, the city used eminent domain to displace hundreds of businesses and thousands of residents from the predominantly Black Lower Hill District. Whether the eighteen hundred families had somewhere to go and settle and sit and live and breathe next didn't matter. They just had to get the fuck out. The arena was razed a few years ago. Now it's a twenty-eight--hundred-space parking lot for the Pittsburgh Penguins.

The answer can be found in East Liberty, where my parents raised our family, a neighborhood that has changed so much in the past twenty years—

demographically, culturally, economically, and even topographically—that it's like a gentrification meteor crashed and demolished everything underneath it so white people could start afresh.

The answer is that Pittsburgh is a city in the same America that owes its vastness, power, and wealth to its plundering of Native people and its centuries of free labor from enslaved Africans. (And also the same America in which, during the greatest economic downturn since the Great Depression, spurred by a pandemic that only sharpened its inequities, its billionaires got $637 billion richer.)

While Pittsburgh has owned up to its disparities, it has never admitted, and will never admit, its intent. These things just happen over time, the city tells itself, like how a yard might tell itself that weeds just grow. And it's this lie that allows the 'Burgh to smile at itself in the mirror and that drives its Black citizens mad. Because Pittsburgh's livability for white people is possible because of what makes it unlivable for Black people. There is no abundance without a permanent underclass. Black blood sustains it. Black bodies undergird it.

I know why Vivienne Leigh Young died. She existed in the least livable body in America's most livable city. I was there, driving my car, when the woman who taught me how to drive, and who'd cosigned the loan for that car, cried when I absentmindedly drove past the house that the bank had snatched from her and Dad. "Damon," she said, her voice barely a whisper, "don't ever take me down this street again." I remember the morning of October 18, 2013, when Dad called to tell me that my mother—his best friend; my sister Jemelle's therapist; my nephew and nieces' Gida; the woman who at sixteen got into Carnegie Mellon; who in 1984 sparked a mini race riot that led to the closure of a deli in Squirrel Hill after the white cashier called her and Nana "black nigger bitches"; who made the best French toast ever; who I never beat in Uno or Connect 4, even when I cheated; who introduced me to Steely Dan and Toni Morrison and banded collars and chicken cacciatore; who came to as many grade school and middle school and high school and college and AAU and summer--league basketball games as she could, driving sometimes, on buses and jitneys most times; and who my four-year-old daughter and one-year-old son are named after—had just died. Was killed.

What do you do when a city you love kills a woman you loved? The obvious answer is to leave. But I bought a house here two years ago. My wife and I are raising our children here. Dad is still here. My memories of Kennywood fits, Eat'n Park midnight buffets, first haircut at Wade's, last dunk on the low hoop at the 'Stein, and Mom, too.

Besides, where would I go?

You Might Also Like