How I learned to love my kinky hair and full lips as a black woman

What does it mean to be black today? For Black History Month, Yahoo Lifestyle will explore this question in wide-ranging personal essays, video features, and Q&As that focus on the nuances of black culture. In this essay, Hypebae associate editor Robyn Mowatt shares her unfiltered journey toward embracing her black beauty.

At 3 years old, I told my mother I wanted to have white skin and straight, blond hair like one of my preschool classmates. I had an obsession and saw these physical features as a symbol of beauty. It was an identity issue that only worsened as I got older and began to bury my feelings about my appearance.

My perception of black beauty was something I had to grow into. Even though I viewed my mother, aunts, and grandmothers as beautiful and played only with black Barbies and dolls, there were plenty of times I looked in the mirror and didn’t see beauty. My eyes always seemed too doe-like, my nose too wide, and my lips were at times too big. I spent my childhood days wanting to disappear and shrink myself in mostly white classrooms, where I was uncomfortable in my own skin. But this was ingrained into my DNA.

My 81-year-old grandmother, who is from Moncks Corner, S.C., wrote in her dream book that she wanted to have daughters that “weren’t her dark-skinned complexion.” The reason? She didn’t want them to endure the teasing and discrimination she faced in the Deep South. So she married a man with a lighter skin tone, later giving birth to four children, including two daughters who were light-skinned.

I was tone deaf on colorism as a child, and I found it annoying that both blacks and whites would ask me, “What are you?” — demanding racial makeups on the spot. I learned from those inquiries that I wasn’t really black because I didn’t “talk black,” and because I didn’t speak Patois, I couldn’t really be Jamaican.

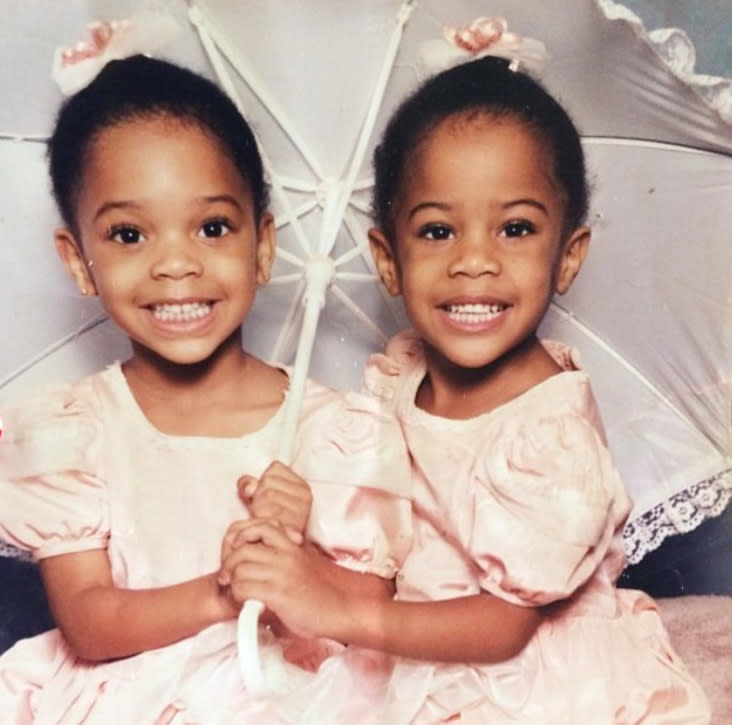

Though I was never teased for the color of my skin, which I believe can be attributed to how colorism runs rampant in the black community, back-handed comments about my appearance became even more painful after my younger sister was born. Her complexion was browner than mine and my twin sister’s, more similar to my father’s complexion.

“You three must not have the same father.” “Who is her dad?” The ignorance and insecurity that could be read through these comments and questions was maddening. But it introduced me to the types of ridicule children could be subjected to and internalize from a young age about hues of black and brown people. So we as a family actively showered my younger sister with knowledge about the beauty of her skin color even though it wasn’t the same shade of brown we were.

Despite my mother’s pro-black approach to raising me and my twin sister, I still wasn’t happy with my physical appearance. My feelings of possessing a lack of beauty were directly connected to my sense of otherness. I was confused how at home surrounded by family I was called beautiful and smart, yet with kids my age, I never fit in.

I would flip through issues of Elle Girl and Teen Vogue and yearn to see images of young girls and women who looked like me. But for years, the representation wasn’t there. Month after month and year after year, I read those two magazines and wanted to be the one writing the articles, or somehow involved with the clothes and accessories featured in the magazines that I felt I related to because I was young, eccentric, and different.

Feeling like “the other” continued into my adolescence. As a light-skinned black girl, I was taunted for “speaking white” or for “speaking proper,” according to my classmates. I was told to ignore the teasing and the name-calling (Oreo, white girl, Valley girl, etc.). This shunning was interesting, to say the least. It was also my introduction to understanding societal norms and interacting with different groups of black people, since my twin and I were bused into Central Florida to attend a magnet middle school.

As a result, I struggled with low self-esteem for years. It was especially difficult dealing with this in the late ’90s and early 2000s, as girl groups like the Spice Girls and Destiny’s Child were very popular. I began to dabble in makeup and was always attracted to outrageous clothes, which I hid behind. My self-expression through clothes and accessories were my way of coping with being teased. I felt transformed when I began wearing foundation because in a way I was trying to transform into someone else. Makeup made me feel less insecure, and when worn with rare sneakers like Shrek Nike Dunks that no one else had at my Florida school, I felt invincible at times. Though these things were really a distraction from how I was feeling on the inside.

When I enrolled as a student at Florida A&M University, I decided to embark on my college experience with an open mindset. Because of this mental shift, I wasn’t as guarded as I was in my younger years. I found a group of friends who were accepting, affirming, and didn’t make me feel out of place, and eventually I became more comfortable in my blackness.

My awakening in college pushed me to embrace the idea that black beauty comes in many different shades, shapes, and sizes. This meant embracing the physical features I despised in my younger years. On this journey, I learned that it’s important for black and brown girls to see images that represent themselves in the media and to be affirmed positively of their beauty throughout their childhood and adolescence.

For years, I connected my self-worth with how others perceived me based on my appearance. I outgrew this and learned to embrace my blackness and what makes me unique. Being different is OK, and that is a part of being beautiful.

Today I can happily say that when I look in the mirror, I see beauty. My reflection shows a young black woman who is a creative at heart. I now see my kinky hair, full nose, and lips as a representation of black beauty. I see beauty as being fully comfortable with who you are.

Read more from Yahoo Lifestyle:

5 black women and men share their unapologetic natural hair stories

The Twitter trend #BlackMenSmiling will have you doing the same

A YouTube Star on Blogging Discrimination and Perfect Selfies