These Are the Lawyers Fighting For Your Abortion Rights

On the morning of March 4, Julie Rikelman will enter the Supreme Court with the rights of at least 1 million women of reproductive age resting on her shoulders. Maybe she will think of the employees at the abortion clinic she is representing, who walk into work through throngs of protesters who shout the workers' children’s names menacingly. Maybe she will visualize the patients at the clinic, who come from Texas, Arkansas, Oklahoma, Nebraska, or even from overseas army bases, to seek an abortion. If she loses the case, the state of Louisiana will be left with just a single abortion doctor.

Maybe she will think of her parents, who immigrated with her to the United States from Ukraine when she was a child, seeking civil rights. Maybe she will tell herself that in a few years her two preteen daughters will be proud of her. She will prepare to argue her first case before the Supreme Court. She will wear a navy blue suit. She will try to not be nervous.

“I care,” Rikelman, litigation director at the Center for Reproductive Rights, reminds herself when she imagines arguing the first major abortion-rights case before the new, conservative-leaning Supreme Court. “I do have an expertise in this area of the law—I live and breathe what the constitutional law is on these issues.”

Rikelman—along with T.J. Tu, her cocounsel—are under pressure. If the Supreme Court upholds the law in the case they are bringing on behalf of their client, June Medical Services, LLC, abortion will be almost completely inaccessible in Louisiana. The ruling will set a precedent that, as Tu describes it, “states like Louisiana can effectively ban abortion without overturning Roe v. Wade.” Abortion may remain legal. But it will also be, for all intents and purposes, banned. “The situation will be very dire,” Rikelman has said.

GL-CP

At stake are two of only three abortion clinics serving women in Louisiana and surrounding states, where abortion is all but banned. If the Supreme Court allows the Louisiana state ruling to stand, it will leave only a single physician to provide abortion care to women in the state. “I’m gonna make it my mission in life to make sure that this law doesn’t shut this clinic down,” Tu told workers at Hope Medical Group in Shreveport, Louisiana, the plaintiff in the case, when he was assigned to it. Women’s lives are on the line.

Tu was raised in Omaha. His father, who came to the U.S. as a child from Shanghai, “instilled in me that do-gooder attitude,” he says. He came out as gay in college in Iowa (“I realized there were important fights that were worth having”), becoming an activist for queer rights and reproductive rights, and working at the ACLU before applying to law school. At New York University, he became editor of the law review, and after he graduated, Tu clerked for now Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor when she was a judge in the court of appeals. He became an expert in false-advertising litigation. He made partner. He kept up his pro bono work. He served as cocounsel on a Supreme Court case about pomegranate juice. It was, by all accounts, a “very fancy career.”

Then Donald Trump was elected. “I was asking myself, What can I do? Can I give money to organizations that I care about? Can I march in the streets?” And then he remembered: He is a lawyer. He thought, he says, “Well, that’s what I know how to do; where can that be helpful?” He reached out to Nancy Northup, the president and CEO of the Center for Reproductive Rights.

“I said, ‘Can I be useful?’ And she said, ‘Absolutely.’”

Leaving a lucrative corporate job as partner to join a nonprofit was, even to some of his more supportive colleagues, “a head-scratcher,” Tu says. The next day Justice Anthony Kennedy announced his own departure—from the Supreme Court. (His empty position was later filled by Brett Kavanaugh.) “People stopped asking if I was crazy,” he says. “Some people may still have thought it was a goofy decision, but they no longer said that to my face.”

GL-CP

Legal abortion is the law of the land…technically. In Roe v. Wade, the landmark Supreme Court decision of 1973, the court found that the right to abortion falls under the right to privacy, which is protected by the constitution. The decision to carry a pregnancy or to terminate it is private, and the government cannot make it for you, the majority of the all-male justices on the Supreme Court of 1973 argued.

To the casualish observer—say, a woman who would consider an abortion if she had an unplanned pregnancy—trying to follow the uninterrupted flow of news stories about abortion restrictions is both numbing and confusing. Two seemingly opposite things are true: Abortion is a constitutionally protected right. It’s also, in many states, almost impossible to access. How can something be both legal and almost completely restricted? It feels like an old-timey riddle, except instead of a question from a mythical creature, it’s a question that can determine the course of a woman’s life. “What does it mean to a patient in Louisiana if Roe is technically on the books but the state is able to completely get rid of all the abortion providers?” Tu says. “In that case, Roe is just an illusion of having a constitutional right.”

Nearly 450 abortion-restricting laws have been passed into law in the U.S. just since 2011, according to the center. The organization’s lawyers have been key in stopping many of these laws from taking effect. In just the last year, the center successfully blocked abortion restrictions in Virginia, North Dakota, Kansas, Montana, North Carolina, Alaska, Kansas, and Mississippi. They have sued to block abortion-ban laws in Georgia, Oklahoma, and Arizona, to name a few. The center has been involved with every Supreme Court case involving abortion since its founding. If you like having the government stay out of your underwear, you might want to thank the Center for Reproductive Rights.

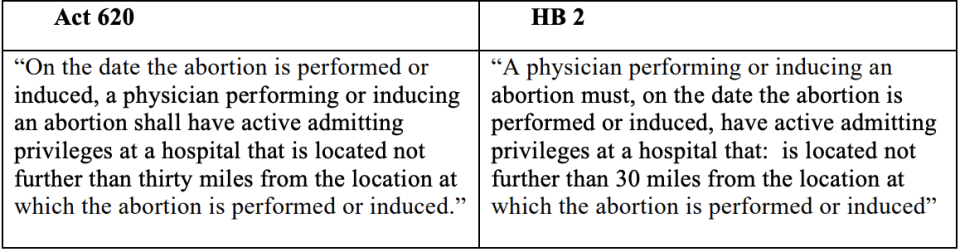

In June v. Russo, as in many abortion cases, lawmakers have created a powerful illusion. The case centers on a requirement that abortion providers have admitting privileges at a nearby hospital for safety reasons. “Admitting privileges” conjures an image of a doctor in a crisp white coat, clean walls, and medical excellence. It certainly sounds like something you would like your doctor to have. In reality, an admitting privilege is a business relationship between a physician and a hospital. It is not a medical license or a merit-based credential.

“Who could argue with the idea that admitting privileges are a good idea?” Tu says. “Well, all the leading medical organizations.” The American Medical Association, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, and 12 other major groups of physicians have come out strongly against the law, writing, “Admitting privileges serve no relevant credentialing function, and physicians and other clinicians are frequently denied privileges for reasons unrelated to their competency.” A landmark report on abortion safety by the National Academy of Sciences in 2018 found that abortion-related mortality is lower than maternal mortality rates for birth, as well as mortality rates for colonoscopies.

GL-CP

The dark genius of passing a law that doesn’t allow abortion providers to practice unless they have admitting privileges is that it sounds like a commonsense safety measure—but in reality it has no medical benefit. Instead, it is a substantial roadblock that would leave the 10,000 women who seek abortion annually in Louisiana with only one legal provider.

Laws like this are called TRAP laws—Targeted Regulations of Abortion Providers. Critics like the lawyers at the center say that lawmakers write these laws with the intent of closing clinics. “The admitting privileges, no doubt, is a way to close clinics in Louisiana,” Kathaleen Pittman, the clinic administrator at Hope who has worked in abortion health care in Louisiana for almost 28 years, said at a press briefing weeks before the Supreme Court date. The law fits perfectly with the playbook Louisiana lawmakers have proudly laid out. “We've been named the top pro-life state in America for the last three years, at least,” former Louisiana representative Frank Hoffmann said at a press conference in 2014. “And we do it through making it tough to get an abortion.” Until Roe is overturned, he added, "we want to make it as difficult as possible."

GL-CP

When Tu arrived at the center in 2018, he was given several assignments, including the June case. “I remember reading the file and thinking, Well, I’m gonna need something else to do; this is gonna be a total nothing-burger,” Tu says. Because here’s the thing: Less than five years ago, the Supreme Court heard a nearly identical case concerning a Texas law—and promptly struck it down as unconstitutional.

In 2016 the Supreme Court ruled in the Center’s favor on Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt, a case about a Texas admitting-privileges law. That law is almost interchangeable, to the word, with the Louisiana case being argued this month. In fact, Louisiana’s law was actually written based on the Texas law. “It’s an identical law, literally identical law,” Rikelman says. Admitting privileges—as well as surgical-center requirements, another part of the Texas law—“[do not confer] medical benefits sufficient to justify the burdens upon access that each imposes,” the Supreme Court found in 2016. “Each places a substantial obstacle in the path of women seeking a previability abortion, each constitutes an undue burden on abortion access.”

Two weeks after Tu was assigned to the “nothing-burger” case he was sure would be struck down due to the clear precedent, the Fifth Circuit court upheld the Louisiana law, shocking legal scholars. The center was headed to the Supreme Court. Again. Center staff compare their lives right now—spending hundreds of hours preparing for a case they’ve already, essentially, won—to Groundhog Day.

“It’s maddening. It’s frustrating,” says Northup. “It’s disappointing that after winning the case which was so important in 2016, that really set a standard to make clear that you can’t have these un-medically-justified regulations that are shutting down clinics, that Louisiana was in open defiance of that ruling.” The idea that the Supreme Court might reverse precedent only four years later on an identical law is alarming, and the center’s lawyers argue that this is a rule-of-law issue that extends far beyond abortion—that if the Supreme Court abandons such a recent precedent, it will shake the foundations of the American legal system. “Every federal district court that has held a trial on a similar law has found that these laws have no benefits and have restricted access,” Rikelman says. In fact, the Supreme Court struck down the Texas law because the court found that it would close more than half of the clinics in the state. The Louisiana law would close two thirds.

GL-CP

A few weeks before her Supreme Court date, Julie Rikelman sat in her office in lower Manhattan, which has a view of the Brooklyn Bridge and sits just above an art installation of adult-size seesaws. She spoke about falling in love with constitutional law, of clerking for the first female justice on the Alaska Supreme Court, of getting a fellowship at the Center for Reproductive Rights as a young lawyer, of becoming the vice president of litigation at NBC, then returning to the center almost 10 years ago as a senior staff member. “She’s an outstanding lawyer, just the best that there is in terms of an attorney,” Northup says.

Rikelman’s colleagues point out, with some awe, her extreme sense of calm. She comes across as the kind of person who could easily weather several hours in line at the DMV and then spend the rest of the day at Ikea. She cares. “She’s very committed to making a fairer world for her girls,” Northup says. Rikelman says she didn’t imagine herself arguing before the Supreme Court. But she knew she’d be doing justice work. “I think I’m working on pretty much what people would have expected I’d be working on from when I was a teenager,” she says.

Rikelman estimates that she works 60 hours a week—more, as the trial draws nearer. She wakes up at 6:30 in the morning to take her kids to school, works all week, and on the weekends she works from the couch with her kids next to her. “They still feel like it’s time together even if we’re sort of snuggling next to each other and they’re reading a book and I’m reading a brief,” she says.

Tu’s workload has lessened slightly, because he’s filed his briefs and won’t be the one actually delivering oral arguments in front of the Supreme Court, but for a while he put in 80- to 100-hour weeks.

But Northup might be the busiest of all. In the weeks leading up to the Supreme Court argument, she led the center in cohosting a presidential forum in New Hampshire at which the Democratic candidates gave long-form public interviews about the judiciary with a focus on reproductive rights. She testified before Congress in support of the Women’s Health Protection Act, a bill that, in different variations, has been introduced to Congress every year since 2013 that would codify Roe v. Wade into federal law, not just leave it as legal precedent. She hung out with Busy Philipps. She spent time with her children and stepchildren.

Northup has been CEO of the Center for Reproductive Rights since 2003, and under her leadership it has won both abortion-rights cases it argued before the Supreme Court, taken on international cases, and multiplied its budget sixfold. June v. Russo may set a new precedent for women’s abortion rights (or lack thereof), but it’s hardly Northup’s only concern—the center is litigating 30 other cases in 19 states, as well as a slew of international cases. “Twenty years ago I used to say, ‘Wear pearls, raise hell,’” Northup tells me, on a day in between testifying before Congress, taking her team to the Supreme Court, and overseeing the center’s annual fundraiser, which Maya Rudolph emceed, in the last weekend of February.

I asked Northup why she doesn’t use that phrase anymore, wondering if she’s going to say that she no longer thinks traditional femininity mixes well with feminism. “Well,” she says, scrutinizing me as if I’m a squirrelly congressman. “I stopped wearing pearls.” (She’s wearing a matte gold chain by Marco Bicego.) Northup was a prosecutor and now she’s a CEO and a mother, and she has brought cases before the U.N. She’s a deadly serious advocate. When, inevitably, casting directors debate about whom to call in to play her in a historical drama, Annette Bening’s name will come up.

GL-CP

When Rikelman and Tu speak about June v. Russo, they dispassionately break down the unconstitutional undue burden that it places on women and the threat to rule of law that they believe could weaken the entire judicial system. Northup does this too, but when asked to explain why abortion is an issue that brings out such primal rage in so many people, especially male lawmakers, her eyes flicker. “You have to understand that the issue about women’s control over their own bodies is situated in a very long history of patriarchy,” she says. “1965 was the first Supreme Court case that said that states can’t tell married people they can’t use contraception. Think about that.” Women have had the right to vote in this country for only 100 years, she points out, and women of color have had it in earnest only since the 1960s. Marital rape wasn’t legally a crime until the ’70s. “This notion that you have a separate physical being that is yours and not either the government’s or your husband’s or any other man’s to control is very deep-rooted.”

Northup isn’t an obvious abortion-rights advocate—she was raised partially in the South in what she calls a “bipartisan household,” with a Republican businessman father and a Democratic social worker mother. And she’s a deeply religious churchgoer.

“I’m very aware that, for some people, it’s been very painful and they’ve been denied their humanity by their religious traditions,” she says. But growing up, her church—she’s a Unitarian Universalist—was active in the civil rights movement and prided itself on its history of abolitionism and suffragism. “The first principle of my church is to promote the inherent worth and dignity of every person,” she says. Sitting in church pews as an undergraduate, not knowing that in her future she would have three trips to the Supreme Court, or visits to Congress or U.N. hearings, she would think, How am I gonna live my life? How am I going to be a moral person? How am I going to live a life that contributes in a positive way to the world, in this very long arc of the struggle for equality, fairness, and hoping that each human being can live a life of potential?

Despite her gold statement necklace, cat-eye glasses, corner office, and date with the Supreme Court, Northrup says she is “fundamentally a shy person.” The fact that there is a direct line between her and millions of women’s abilities to control their own body is stressful, she acknowledges: “100%.” How does she handle it? “It’s actually a churchy concept, which is that we are stewards for an institution,” she says. “I take very seriously, and with great gratitude, the fact that I am able to be in this role as a steward for this institution at this time, and someday it will be someone else who will take the mantle from there.”

But for now, the mantle is heavy around her shoulders—and Tu’s and Rikelman’s. Two weeks before their Supreme Court date, the three of them sit in a conference room at the center for a press conference. An all-women camera crew collects footage for a documentary on the center. Northup introduces everyone, and then invites the Hope Medical Group administrator, Kathaleen Pittman, to speak from Shreveport via conference call. “With the increase in the anti-abortion rhetoric, we’ve seen an increase in protest activity,” she says in a buttery Louisiana accent. “Our concern for our patients, our staff, our physicians, it’s very real…. There is very little we can do to protect ourselves.”

GL-CP

For women in Louisiana, access is nearly impossible. And for physicians, providing abortion access is dangerous. “I get to go to work every day in the relative comfort of an office here in New York,” Tu says. “I know they have to go into a building where they’ve had to brick up all the windows because they’ve been the subject of Molotov cocktails, bomb threats, acid attacks. A man wielding a sledgehammer once came into the clinic.” Rikelman isn’t afraid for her own or her family’s lives, she says, but she’s afraid for the Louisiana workers. “People are protesting at their children’s school or outside their house,” she says. “They really have to feel for their children’s safety.” But providers continue on out of concern for their patients—Pittman told journalists gathered for the press briefing that, once, the clinic suffered an acid attack and tried to close for the day because of acid fumes. Even though poison hung in the air, “not a single woman wanted to reschedule,” she says.

The Hope doctors, who serve as plaintiffs in the case, are labeled in the court filings as John Does for their protection. If the Supreme Court rules against the center, all but one of the providers will be out of work. The Hope clinic will likely close, and abortion will be out of reach for more than 1 million women. “Roe becomes meaningless if there is no access to abortion,” Pittman said at the briefing. “These women that we work with now do not have the means to travel, to fly out of state…. They have every right to receive their care here in Louisiana.”

Rikelman and Tu have Supreme Court precedent on their side. They have put years of work into this case. They have given their lives to it. They are ready. But the thing is, even an abortion-rights win in the Supreme Court this spring doesn’t ensure a happy ending. Even though the Texas admitting-privileges law was struck down by the Supreme Court in Whole Woman’s Health, by that time half the clinics in the state had already closed. Years after that victory, the majority of the Texas clinics that closed haven’t reopened. Even when abortion rights win, anti-abortion lawmakers get consolation prizes. “We believe that we should win this case,” Northup says. “But we’re not folks that say, ‘Well, if we lose the case, it’s game over.’”

GL-CP

“We are not going back,” Northup frequently says when she discusses abortion law. She means that no matter what happens with Hope, or with the Women’s Health Protection Act, or even with Roe, “We’re not going to go back to women not being able to control their own reproductive health care.”

But it’s hard not to feel—with the waiting periods, the threat of the shifting Supreme Court, and the seeming infinity of new TRAP laws—that we haven’t lost ground already. Women around the country will have to put their hopes on Julie Rikelman, on T.J. Tu, on Nancy Northup, and on the anonymous, endangered physicians testifying in their case. “I care,” they will remind themselves, as arguments begin. “I have expertise,” they will think, as they set the course for the health and well-being of millions of women.

And as Northrup says, they will remind themselves, “Women are not going back.”

Jenny Singer is a staff writer for Glamour.

Originally Appeared on Glamour