The Last Man Up

For the past 16 years Tom Walsh has spent every Independence Day on a mountaintop above Seward, Alaska, tallying the agony.

Walsh is the lead midcourse timekeeper for the Mount Marathon Race, the second-oldest mountain footrace in the world and, after the Iditarod sled-dog race, the most famous race in the 49th State.

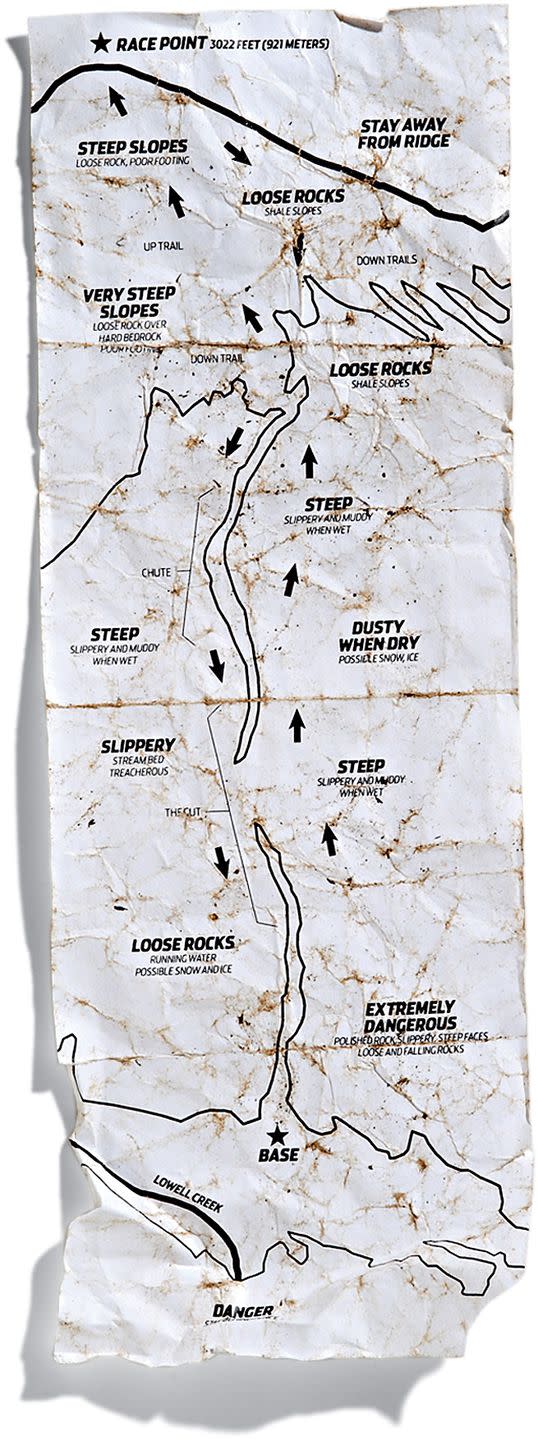

Contrary to its name, the Mount Marathon Race isn’t a legend for how far it stretches through the vastness of Alaska, but rather for how much unpleasantness it crams into so small a package. Starting in downtown Seward, racers run a half-mile to the foot of Mount Marathon, then scrabble about 2,900 vertical feet straight up cliffs and mud and shale before finally staggering to Race Point. There, Walsh and others note their time and bib number, hand them water, and send them hurtling back downhill in what more resembles free-fall than running-over snowfields and rock fields and waterfalls and crags-until they reach the finish line back on the streets of Seward.

All of this occurs in 3.1 to 3.5 miles, depending on your route, and on trails so close to town that spectators waiting at the finish line can follow nearly every tortured step high on the mountain. By yardstick the contest is briefer than a postwork jog around Central Park. By every other count-sheer adrenaline, lung-bleeding exhaustion, potential for disaster per mile-there may be no other run like it in the world. Blood flows freely. Bones break frequently-arms, shoulders, cheekbones, legs. Sometimes, worse happens. The race has been run 85 times, and it is wildly popular. As an isolated people who long ago learned to make their own fun, Alaskans will tell you without much hyperbole that Mount Marathon is their Olympics.

Independence Day under the undying Arctic sun can be warm and lingering and nectarine-sweet. Last July 4 wasn’t one of those days. By afternoon the weather was as bad as Walsh could ever recall-windy and rainy, high 40s. He and coworkers had been on the mountain since morning, first to work the women’s race, then the men’s race that began at three o’clock.

A bit after five o’clock a longtime racer straggled to Race Point, a false summit marked by a large rock. The racer said he was the last guy. Walsh and his shivering comrades waited about 45 more minutes, then headed down the empty peak.

The Mount Marathon course roughly describes a treble clef-runners don’t descend the same route they ascend-and as Walsh hiked down that afternoon, he saw another man slowly climbing, about 100 yards away, and dressed lightly as racers do, in black shorts, black T-shirt, black headband. It was more than two hours since the winner had broken the tape down in town. “How far am I from the top?” the racer called out.

“About 200 feet,” Walsh yelled back.

The man asked if he could still “get a finish.” Walsh told him to loop the rock atop Race Point and go down via the descent trail. Scarves of fog slid past them. But Race Point was still visible just above, as was Seward below, so close-seeming that the music and firecrackers of the impending party drifted up on the winds.

What happened next Walsh has replayed untold times in his head. Did he miss something? Was the man sick? Was he injured? Should he have made him turn around immediately on the sketchy up-trail? “There didn’t seem to be any red flags,” Walsh told me weeks later. The man was plodding, sure-but otherwise he seemed fine. So Walsh let him go.

“What’s your bib number?” Walsh called out before they parted.

“Five-four-eight,” the man said, and he immediately started upward.

Walsh headed down, but first texted race officials: Bib number 548 would be home in about an hour and a half.

But the man wearing bib number 548 didn’t return in an hour and a half. Michael LeMaitre has never come down the mountain. Mountain rescue experts, firemen, state troopers, search dogs, helicopter pilots, volunteers, and LeMaitre’s family spent thousands of hours scouring the mountain for him. They have yet to find even a single clue to his fate.

Think about that for a moment: 1.5 miles up. Roughly 1.6 miles down. Hundreds of runners within view of thousands of fans, and a man simply vanished. How the hell is that even possible?

It is as if, one exasperated relative told me, “The mountain swallowed this man.”

Seward is a town unburdened by stoplights at road’s end 126 miles southeast of Anchorage, its 2,700 year-rounders residing on a neat thatch of rectilinear streets named for presidents everyone can still agree on: Washington, Adams, Madison. Founded to be Alaska’s railroad gateway, today it is a town of lesser ambitions-a fish-processing hub turned tourist burg at the head of mountain-ringed Resurrection Bay, an inlet of the Gulf of Alaska that can glow the unreal green of Immodium A-D, thanks to the glaciers that are patiently grinding the surrounding peaks to flour and shipping them to sea on muscling rivers. When the sun shines, this place is a calendar shot of Alaska’s greatest hits: Ocean. Mountains. Wildlife. Ice. Often all in one frame.

After Labor Day, when I arrived, nearly the last of the wedding-cake cruise ships had scooped up its Sansabelt-slacks’ed passengers and sailed south for Seattle. The herd of RVs that migrate here each July and August had drifted north to rental lots in Anchorage. The brief, frenetic, money-making Alaskan summer was over, and an autumnal drowsiness had taken hold of town. Locals had already tugged on their winter “Seward Slippers”-tall Xtratuf rubber boots. At gewgaw shops like Once in a Blue Moose, with its Bear Poo Chocolate Peanut Clusters and “Alaska: Just for the Halibut” T-shirts, the discounts had begun.

It was from downtown where I first looked up and saw Mount Marathon-a great green pyramid, fat at the base and tapering with geometric precision for 3,022 feet to a rocky point. (Out of sight it climbs more than 1,500 feet higher.) In a land of big peaks, what makes Mount Marathon remarkable isn’t that symmetry or height, however, but sheer insistence: As it stretches north for nearly a mile, the mountain forms almost the entire western border of town. It is literally Seward’s backdrop and backyard, its playground, constant neighbor and companion. When you look to the western sky, it fills the eye. It refuses to be ignored.

Like many contests of dubious judgment, the race started with a bar bet: Who could run up the big peak behind town and back in under an hour? On Independence Day 1909, Seward was a 6-year-old pioneer village full of miners and other hard men. Al Taylor, a dog musher and one of those strong fathers of Alaska, reportedly took the wager. Dressed in wool pants, leather boots, and his Sunday-best white shirt, Taylor pounded up the dirt streets and into the woods. He reappeared just over an hour later and bought a round for the house, according to Millie Spezialy’s history of the race. In 1915, the race up Mount Marathon-the peak was soon named for the punishing run-became an annual July 4 event. Since then, only capitalized calamity-World War, Great Depression-has canceled the contest, and then only temporarily.

One morning I headed to the trailhead with Sam Young. Young is 58, with a long upper lip, a high forehead that slopes to neatly combed-back hair, and the flatness of a Nebraska upbringing still in his voice; in another era he could have been a Dust Bowl preacher. Only his battered running shoes hint that Young is a 2.5-time Mount Marathon winner. (The “half” is race lore: In 1986, after a spicy back-and-forth duel, Young and Bill Spencer, who holds the course record of 43:21, agreed to cross the finish line hand-in-hand.) Young has run it more than 20 times, and when he speaks of the race, his soft voice seems to cradle it like something of great value.

We stepped into the forest on a scratch of a trail. Suddenly there was mountain. No warning, no foothills-just 50 feet of rude geology. The course at times isn’t one trail, but a veinwork of paths-and Young started up one called the Roots. Soon I was 40 feet up a slick wall of mud, clinging to the bones of hemlock and spruce, wishing I had a belay. Gravity tugged patiently, waiting for its chance. “You slip here, your ass is grass,” Young shouted. “Now imagine doing this while buzzing with fear, adrenaline, and oxygen debt.”

For decades, fewer than 10 runners competed, and it was a free-for-all-any way up and back was fair game. Men sprinted down alleys, clambered over cars, sabotaged each others’ shortcuts; the night before, fences sprung up in yards that had never before boasted one. Winners won fat purses, their fame carried across the state by bush plane. (By 1950 the prize was $2,500-about a year’s pay at the time. Now, instead of cash, winners get a trophy and free entry into future races.) The race’s popularity swelled with the running boom of the ’70s. Today, a cap of a thousand men, women, and children as young as 7 turn out, from housewives to elite athletes ($65 entry for adults, $25 for kids). About 90 percent of the adults are returnees; until a recent rule change, all finishers gained entry into the next year’s race. Few relinquish their spot-and lottery bids are coveted. The only thing harder than running Mount Marathon, the saying here goes, is getting the chance to run.

“Harder” seemed unlikely. After the Roots, we plunged into the Alaskan bush, which in summer is a rioting jungleland-five-foot pushki with its blistering burn, hypodermic devil’s club, alder as tight as prison bars. This “Little Shop of Horrors” crowded the trail, grabbing, stinging, thickening the air with humidity. At one point Young took a step off the track and nearly vanished into the green.

The path itself averages 38 degrees, or roughly the equivalent of one of those Eastern ski runs with a name like “Widowmaker” or “Paul’s Plunge.” Frost it with mud that goes snot-slick after every frequent Alaskan rain, and it becomes a gruesome alpine Slip ’N Slide. Don’t wear your tennis whites. “You’ve got to put your hands on that mountain,” Brad Precosky, a six-time men’s winner, had told me about certain parts of the ascent. Now put yourself nose-to-butt on this greased 3,000-foot ladder with 175 others. Seen from downtown, the up-trail is a grim, slobbering conga line of humanity.

Not for the best racers, though. Moving high above Young, I asked to see his competition form. He Gollum’d past me, his back bent and breath measured-a simian out for a postbanana stroll. A decently fit guy, I tried to keep Young’s pace for 50 yards and nearly upchucked my breakfast frittata. Not even halfway up, sweat already spilled from my chin, and each calf was asking what the hell was going on. I slipped. Slid. Took a step. Slipped again. Ahead, Young kept moving higher. He fed off the altitude, growing more talkative as he climbed, casually mentioning how he used to roll rocks down on the competition to distract them. “Small stuff, nothing that would hurt anybody,” he said. “There’s a lot of trash going on up there.”

If it seems strange that anyone could embrace such suffering, Alaskans show no such dissonance. Each Fourth of July holiday more than 25,000 people descend on little Seward to drink beer, squint at the lame fireworks that fizz in the twilight of an Alaskan summer midnight, and watch the race. Proportionately speaking, in unpeopled Alaska, that’s close to all of Pennsylvania turning out to cheer a Punxsutawney turkey trot. Fans jostle five-deep behind the barricades at the finish line and pool at the mountain’s base like NASCAR fans bunching at turns in hopes of witnessing mayhem. The Anchorage Daily News, the state’s largest newspaper, covers the race as if it were the Kentucky Derby-dissecting course conditions, handicapping the top runners.

One beautiful ex-racer with the wonderfully Pynchonesque name of Cedar Bourgeois told me with damp eyes how the race had taught her skills she’d never had before-drive and mental discipline. Bourgeois is a local celebrity, a Seward-raised girl who won the women’s title seven times in a row. Today, she owns Nature’s Nectars, a coffee shop in the harbor that pours some of the state’s best espresso to groggy fishermen. The Mount Marathon Race, she said, had done nothing less than change her life. “I would have to equate it to motherhood.”

Young and I hit the halfway point, where jungle yielded to tundra. Above us a dim trail zippered up a hard gray forehead of shale to Race Point. The day blossomed around us-the Kenai Mountains pinned up a mouthwash-blue sky. Tour boats bound for Kenai Fjords National Park dragged their wakes up the bay.

On race day, there’s no time to sightsee. After Race Point comes a caveman’s steeplechase. Runners hurl themselves down the mountain at a full sprint. (After ascending in about 33 minutes, elite downhillers like Precosky will plunge from the top to the finish line in less than 11 minutes. The fastest on record is 10:08.) First they scramble down a long, steep snowfield at highway speeds, then run through shin-deep beds of loose shale that feel like sandboxes of shattered glass. Young flew down it with the poise of a mogul skier.

It’s a helluva staircase. Just as heart and quads are red-lining, runners then hit the Chute, halfway down the mountain. It’s a tilted gun barrel filled with scree or snow that funnels down to a small gulley called the Gut. The Gut’s centerpiece: a pretty creek dotted with yellow monkey flower and three small waterfalls. Runners have to gallop down this creek, which is strewn with what feels underfoot like wet kitty litter. At one point I slipped, lunged for a lifeline, and grabbed a fistful of devil’s club, a feeling not unlike squeezing your mother’s pincushion.

By this point, “People don’t know their names,” Young said. “They are unconscious, the walking dead.” Now appeared the final obstacle between racers and the crowd’s embrace: the Cliffs, several nasty crags, perhaps 25 feet high and sometimes glazed with rain or dust. Young picked an easier line for us. I was so tweaked, I nearly crab-walked down it.

Even so, the worst part of the race is yet to come. After so much up and down, the final 1,000-meter sprint to the finish line on nearly flat asphalt is excruciating, race veterans told me. “Everybody knows how to run on the street,” Young said, “but not after you’ve been through a blender.”

Why would anyone do this? you ask. The answer is that the peril of the Mount Marathon Race and the pain it inflicts are the very things that give the event its enduring allure; you could even say they are essential. Decades before Tough Mudder began roughing up paying customers, people were slapping down their money, then falling down-hard-at the Mount Marathon Race. On the flying descent, runners have fallen and had to have six-inch spear points of shale extracted from their hindquarters. Seward Fire Chief Dave Squires, who has aided injured racers for 26 years, told me he has seen everything from dislocations and neck injuries to angry tattoos from sliding down snowfields. A woman once rolled her ankle while evading a pissed-off bear. Another year a man was impaled by a tree branch. One roasting July 4 in the 1980s, 53 people were treated for heat illness. Squires has seen racers suffering from compound fractures-bones actually jutting from their bodies-still running toward the finish line. “Sometimes not very good,” he said, “but they’re still running.” Among three serious injuries in last year’s race, an experienced mountain runner from Anchorage chose an unusual line above the Cliffs, tripped, fell-and suffered lasting brain trauma. A pilot from Utah slid 30 feet down a muddy ramp and off the Cliffs, lacerated her liver, and was hospitalized for five days-saved only from graver injury by a quick-thinking EMT who broke her fall.

In 2009, U.S. Ski Team member Holly Brooks was leading when she collapsed in front of Seward’s emergency room, not far from the finish line. She had acute exertional rhabdomyolysis-her muscles literally shredding themselves. It took doctors an hour to find a noncollapsed vein in which to insert an IV. Soon after, Brooks checked herself out against their orders and limped to a 212th-place finish so she could run again. Last year, she won.

“Many people say that if you’re not bleeding from at least one spot when you get down, you didn’t try hard enough,” Lori Draper, a longtime member of the race committee, told me with a smile. Organizers proudly say that the race is never canceled due to adverse conditions.

Even on a normal day, the mountain can be unforgiving. Every year hikers must be rescued. A decade ago some Navy SEALs, the service’s hardmen, went for a hike, worked their way onto cliffs with no exit-and had to be plucked to safety by helicopter. Over the last 25 years, the mountain has killed three hikers, though previously never during the race.

Earlier, when we finally had reached the trailhead where we’d begun, Young had taken my hand. “Did I see blood?” he had asked, examining a sliced finger. “This mountain gets a piece of you, every time,” he’d said.

And here you, the reader from the Lower 48, must understand something: This is how Alaskans like their home.

Alaska is different from anyplace you have ever seen. Everything is bigger here: the animals. The weather. The man-eating topography. In Alaska humans still don’t matter for much. “Out of the car, into the food chain,” locals like to say. Wilderness? It’s not some abstraction; it lives at the end of Washington Street. Go on a hike among the bears and cracking ice; feel the unease at your own contingence in the face of so much Bigness-the flip side of which is an almost electric thrill. This is why Alaskans love this country, and why they stay: to feel the surer pulse that thrums closer to the sharp edge of the blade.

Here you can test yourself daily against the country’s harshness. And if you measure up, life feels that much fuller, the pulse that much more vibrant. “There’s something beautiful,” Bourgeois said of the best downhillers, “to see a dance made out of chaos.” And if it sometimes draws a little blood? Well, that’s just the world telling you that you’re still alive.

There’s just one caveat that comes with loving a place like this-with loving its fractured glaciers and its posing moose and the wisps of the northern lights on blue-cold nights when the mercury pools in the bulb, and with loving its mountains so much you will heave yourself against them in a muddy embrace: You must never forget that Alaska doesn’t love you back. The moment you forget that, the moment you let down your guard, this place will kill you.

The crazy Frenchman loved Alaska. He loved its overflowing wildness, its bear-filled forests, its fat halibut that sulked deep in its lightless ice water, waiting to be suckered topside by a flashy jig to a hot grill and a cold lemon wedge. After high school Michael LeMaitre could have gone to Syracuse University to run track. But eventually the tall, blue-eyed New Yorker made it to the far north and enrolled at the University of Alaska Fairbanks. There he met Peggy, his wife.

Alaska in the early ’70s was filled with young people eager to explore a state that was even younger than they were. Michael and Peggy took their growing family everywhere: Camping. Hiking. Fishing in Seward. Many summer Fridays after work they trooped their three young kids into the RV and pointed it toward Homer, on the Kenai Peninsula, where they’d fish all day, pull up their crab pots, and, in the dusky Alaskan midnight, light a bonfire on shore and gorge on the world’s best king crab and shrimp. “We had no idea how good we had it,” said Peggy, today a tough, blond grandmother of three.

It was two months after Michael’s disappearance. Peggy stood and left the dining room of her Anchorage home where we were seated. She’d been describing a man who was always in motion, and now she returned with the evidence: a stack of frames bearing his Ph.D. in business administration; a dozen training certificates; his accreditation as a grief counselor. (Frequently helping others, he volunteered at a hospice program and counseled children orphaned by the 9/11 attacks.) For the last 18 years he had worked at the local Air Force base, most recently writing résumés for colonels and privates alike as they transitioned out of the service. At home Michael, fit and younger-looking than his 65 years, was the grandfather you always wanted-a big kid who was the first into, and the last out of, Big Lake’s icy waters, or the only one to take granddaughter Abby on the Apollo, the scariest ride at the Alaska State Fair.

That enthusiasm reached beyond the LeMaitre family room and into the outdoors. And here a pattern continued: Michael never let the details complicate what he wanted to do. In the ’80s when he wanted to learn to cross-country ski, he didn’t take lessons but signed up for the Iditaski (now the Iditarod Trail Invitational), a 210-mile wilderness race in which entrants drag their own supplies on sledges. Twice he won the “red lantern” award that’s given to the last-place finisher (the second time because he stopped to help a fellow skier). As LeMaitre saw it, grit and determination-let’s call it stubbornness-could see a man through a lot, and he had buckets of both.

Another time LeMaitre and his best friend Rich Ansley installed an overpowering motor onto LeMaitre’s dory in Anchorage and sailed toward Homer, more than 120 nautical miles away. The boat’s fiberglass bottom literally began peeling apart in the middle of the treacherous Kenai Narrows. They siphoned water out of the leaking boat, stopped to make some temporary repairs, and puttered on to Homer. The next morning, they took the boat fishing on Kachemak Bay.

“We’ve had a lot of outings,” Ansley recalled, “where we said the only reason we’re alive is that we entertained God.”

LeMaitre more or less subscribed to “the duct-tape answer to life,” his eldest daughter MaryAnne told me from her Utah home. “He wanted to have fun.” For her father the journey was the adventure-and if you map every moment, “you’re taking away the spontaneity, the come-what-may feeling.”

Back in Peggy’s dining room, her son-in-law, Curtis Lynn, looked at me across the dining table and asked, “Are you familiar with the military term FIDO?” I gave him a blank look. “Fuck It. Drive On,” Lynn explained. That was Michael.

And the thing is, he always made it work. There were a score of dodged bullets-the dead engines, the hunting trips that went sideways. But those just became good stories. That’s why, when the CB radio craze hit in the mid-’70s, Peggy’s handle became Lucky Swede, MaryAnne was TwinkleToes. And Michael? He became the Crazy Frenchman.

It wasn’t out of character, then, when LeMaitre last winter applied for-and won-one of 60 men’s lottery spots in the Mount Marathon Race. Soon the rookie letter arrived, with its bald admonition: “Do NOT make the July 4th race your first trip up Mount Marathon!” Peggy and youngest child Michelle, a nurse, tried to talk him out of it. He waved them off.

The night before the race, the LeMaitres and hundreds of fellow racers gathered at Seward Middle School. Outside, it was already raining-had been for days. After the annual raffle and auctions, the doors of the gymnasium were ceremonially closed for the mandatory rookie safety meeting. The gym was so packed that Michael and Peggy sat on the floor.

“If you have not been up that mountain before, you should consider going home right now, and you should not be in the race,” Tim Lebling, who gave the prerace safety talk, told the crowd. LeMaitre had always been in good shape-he lifted weights and ran at the gym regularly and had finished a 12K a month earlier-but the weeks leading up to the race had been busy. He’d run few hills, and he’d never gone to Seward to scout the course. But now, if he heard the warning (Peggy doesn’t remember it, though several others who were in attendance do), he didn’t move.

“No one’s gotten up, so I’m assuming everybody’s done it,” Lebling continued. He then showed a short video and a slide show of the cavalcade of hazards-bears, falling rocks-and important landmarks, including the “turnaround rock.” Lebling talked about how slick the course was this year, and about the winter’s record snowfall that had left crumbling snow bridges high above rumbling creeks. “Remember-you can’t beat the mountain,” the safety video concluded, “but the mountain can beat you.” Yet even the video seemed to capture this race’s schizophrenic relationship with danger: Some of those images of injuries and flying bodies were set to an adrenal-squeezing speed-metal soundtrack.

The next day was a pluperfect small-town Independence Day. Local guys sang the national anthem. Sacred Heart Catholic church hawked drumsticks at its annual chicken barbecue. A parade celebrating “100 Years of City Government” marched down 4th Avenue with kids dressed as future city-council members. And all day long, people in waves ran up and down Mount Marathon, to crazed cheers-first the shortened kids’ race, then the women’s race.

After the women ran, spectators at 4th and Adams crowded in front of the bronze bust of eponymous William H. Seward, negotiator of the purchase of Alaska from Russia in 1867, who cast his jowly gaze over the men’s starting line. The mood was expectant, but the weather wasn’t great-chilly, the pigeon-colored skies threatening rain.

“Are you sure you want to do this?” Peggy asked her husband.

“I’m going to be fine,” he replied. “I’m going to take it slow.”

“Honey, you come back to me.”

He kissed her.

“I will. Don’t worry. I’ll be back.”

When the gun sounded for the second wave of the men’s race at 3:10 p.m., LeMaitre and about 175 others charged through a tunnel of noise up 4th Avenue. They ran past the fire hall, past the Chinese restaurant, past the other Chinese restaurant, past the United Methodist Church that advertised “Worship at Moose Pass, 9 a.m.” After two blocks the runners took a hard left on Jefferson Street and ran beneath the large mural of the Mount Marathon Race, painted on the side of the senior center and bearing a list of past winners in the way another small town might celebrate its prized graduates or war dead. They passed a low-slung building with a large red cross-the hospital. The road kept rising. In another block the asphalt turned to gravel. LeMaitre and the others ran past a warning sign at the foot of the mountain that read, “Going down is even more dangerous than going up.” Then the runners ran out of road entirely and faced the great green bulk of the mountain. They started to climb.

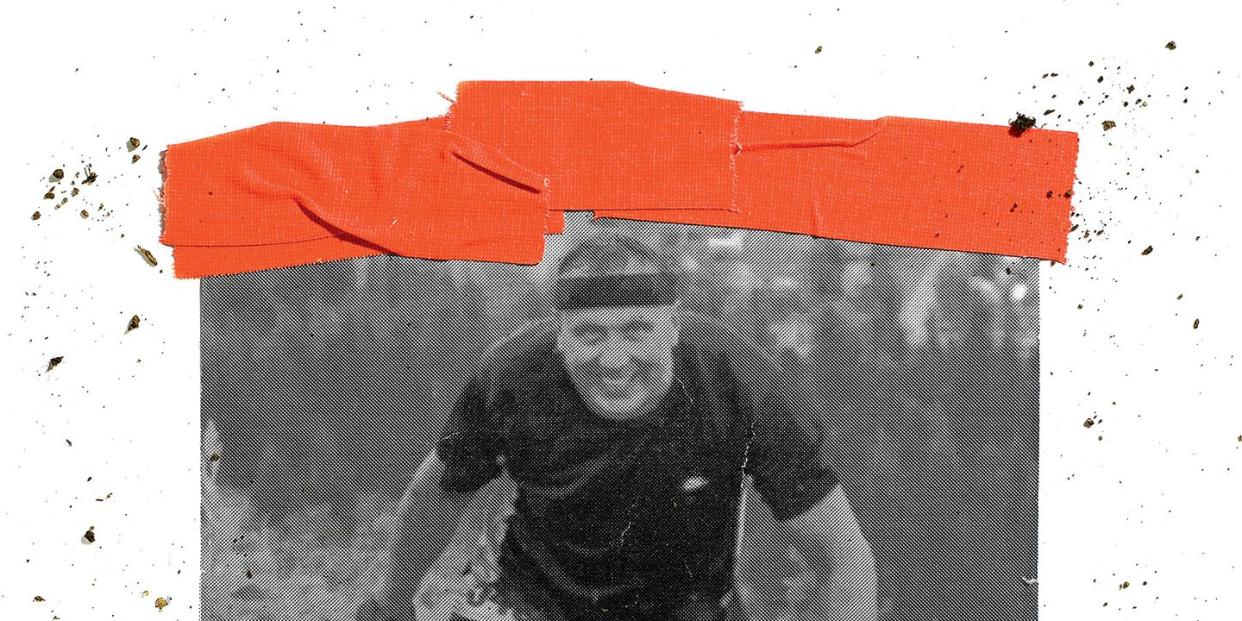

In Peggy’s dining room stood a large photograph, the last ever taken of her husband, shot by a photographer on the course at about 4:30 that day. In it, Michael is just emerging from the thick brush midway up the mountain. Seward lies below, a toy landscape of streets and yards as neat as an ice tray. There is no one behind him. His knees are dirty, his gloves are soiled. He is completely soaked through by rain and sweat-shorts, shirt, headband. What you keep returning to, though, is his face. It isn’t a face of misery, or complaint. The blue eyes are wide. The grin is gritted but large, even a little wild. Last place doesn’t faze this face at all; it has been there before. You realize then that you know this grin: It is the grin of the Crazy Frenchman.

Fuck it, the grin says. Drive on.

Peggy shivered alone in the rain, honking her car’s horn and screaming her husband’s name at the base of the mountain to guide him home.

By eight o’clock when he had not appeared through the spruce-two hours after Tom Walsh had radioed to race officials that LeMaitre would soon be on his way down-the family notified authorities. Hasty searches turned up nothing. The temperature was dropping, the rain increasing. By two in the morning, an Alaska State Troopers’ helicopter equipped with infrared radar sensitive enough to see footprints left in snow arrived and scanned the mountain through the dusky night. Searchers landed and blew whistles-still nothing. Had anyone looked up from town in the late afternoon, he might have watched LeMaitre, seen exactly where he’d gone-he was that close. But the race was long over; everyone had turned his back on the mountain, toward cold beers, hot showers. The evening ahead. Now it was sleeting at Race Point. LeMaitre had been on the mountain for 12 hours dressed only in a T-shirt and shorts. Searchers feared that if he wasn’t already injured, he was almost surely suffering from hypothermia.

The next morning the 210th Rescue Squadron of the Alaska Air National Guard, which specializes in searching for downed pilots and missing hikers, arrived with its HH-60 Pave Hawk helicopter for another infrared scan. The two choppers stalked the mountain all day. On the ground a team of 40 searchers, which soon ballooned to 60 or more, canvassed the mountain. They tried to think like the lost man: Did LeMaitre hike right past Race Point and continue up a goat path toward the true summit-only to slip down treacherous cliffs beside the path? Did he fall through a melting snow bridge created by the streams that run beneath the lingering snowfields on the racecourse and now lie, injured, out of sight? Desperate, did he beeline straight for Seward through the impossible jungle of alders and devil’s club? In the following days they checked everything, to no avail-even tying strips of pink and orange surveyor’s tape to branches to mark the places searched. Weeks later when I climbed it, the mountain remained tinseled with hundreds of poignant DayGlo ribbons, each one a hope unfulfilled.

Days passed. Rescue quietly became recovery. The barstool sages jawed that LeMaitre had pulled a fast one on everybody. “He’s in Cabo,” they said, “nursing a frosty margarita.” But for many Sewardites the hurt was personal. “This is our mountain,” Sam Young told me. “We can’t have someone up there suffering.” He and others took days off to search the mountain-some with teams, some on their own.

But where did LeMaitre go? The high tundra and rock slopes were easily enough searched. Soon the snow tunnels also had melted out, revealing nothing. Only one general scenario seemed to fit: Something sudden and drastic happened to LeMaitre-a fall? A broken ankle in the scree? A heart attack? He managed to reach the worst of the brush, or else wandered into some of Mount Marathon’s frightening, unseeable cliffs-dense and difficult areas where searchers might have missed him. Shock and hypothermia took hold. And he died there.

But the mountain, so much larger than it looks from town, was loath to return what it had taken. Its rocky slopes ripped spiked crampons from searchers’ feet. Its muddy slopes twisted their ankles. And it kept raining. Four days after LeMaitre disappeared, the state troopers, who’d spearheaded the search, ended their effort. The Seward Volunteer Fire Department kept looking. A cadaver dog arrived from Oregon. Friends pored over high-resolution photographs. The LeMaitres’ son, Jon, came to Seward from Anchorage to comfort Peggy during the search. Daughter MaryAnne flew up from Utah and stayed for six weeks, climbing the mountain’s gullies with volunteers. Once, she steeled herself to poke through fresh bear scat on the trail, looking for a bone, a scrap of clothing, any grisly hint of her father’s whereabouts. “If it would’ve been me on that mountain-I know my dad. He’d be doing the same thing,” she told me later as she fought back tears. “I know he wouldn’t give up on me.”

Finally even Chief Squires reluctantly called off the fire department’s effort, hoping that when autumn stripped the jungle, a clue would appear. But soon the autumn too would pass, and then the snow would fall, and still, nothing.

In mid-August, before MaryAnne returned home, she headed up the mountain one last time. She left at three o’clock, arriving at Race Point nearly exactly when her father did. She sat by the turnaround rock and wept. Then she pulled a Dremel tool from her knapsack and carved “I LOVE YOU DAD” into the rock. Having experienced the mountain and Seward for these weeks, she wrote friends afterward, “If this ends up being my dad’s final resting place, he is happy here.”

Volunteers were still on the mountain when the soul-searching, and the questions, and the finger-pointing started. Should the race timekeepers have left LeMaitre? Shouldn’t he have been stopped? Why didn’t officials know who remained on the mountain? Who is responsible?

Two months before the race, former race director Chuck Echard had warned in The Seward Phoenix Log that race directors were asking for trouble by boosting the cap on adult racers by another five entrants last year. More bodies on the mountain meant more flying rocks, more unprepared racers. “Take care of the runners and the mountain,” Echard cautioned. “Not everyone can run the race.” Women’s champ Holly Brooks caught the thoughts of several people I spoke with when she said, “I’m kind of surprised that something like this didn’t happen sooner.”

“Do we need to change some things? Of course we do,” said Flip Foldager. Foldager is the 55-year-old member of the race committee with a push-broom mustache who is patriarch of one of the first families of the Mount Marathon Race. Officials, for instance, recently put a new rule in place to turn back slowpokes if they don’t reach the mountain’s midpoint within an hour.

But many Alaskans-organizers, runners, even the editorial writers at Anchorage Daily News-reacted to LeMaitre’s death with a lion-like protectiveness toward the race. They sniffed talk of any big changes suspiciously. When I was in Alaska, the adjective that modified the Mount Marathon Race the most-it dangled from the name proudly, a little provokingly-was “dangerous.” It was this event’s red badge of honor. Without danger, there was no race.

“It’s not a safe race,” Foldager told me flatly over beers one evening. “We have to manage that as well as we can.”

But don’t misunderstand: You can’t put bumpers on a race like this, he said. The mountain won’t allow it. Helmets? Ropes? Cover up one danger, another still lurks. Just as important, Alaskans won’t abide it. Danger is in the very marrow of this contest. You cannot separate the two. It is part of its deep mystique. Cancel the race? Ha. People will run it anyway, guerrilla-style.

“The only way you’ll ever make the Mount Marathon Race safe,” Foldager told me, before finishing his beer, “is by not doing it.”

And time and again during my visit, people inevitably turned the blame back on the missing man. “We were unprepared for someone being that unprepared,” Draper, the race committee member, told me. Many locals see Alaska as the ultimate non-nanny state. Yes, there is community, the kind that emerges when people must rally against outside forces. But at the same time, there’s still a frontier attitude, and the elbow room to go with it; you can have all the rope you want to lasso your big dreams and adventures-or all you need to hang yourself. The lesson: Don’t look to anyone else for help when the grizzly charges and the rifle jams. You made your bet against this country. It’s your fault if you come up short.

There’s a brutal fairness to this sentiment, but I left these conversations feeling that it’s too easy to write off Michael LeMaitre as careless, reckless. How many of us have had near-misses-the somersault over the handlebars 10 miles from the trailhead, or the mini avalanche deep in the backcountry-and then laughed about those epics around the campfire later on when all was well? Have you ever thought how close you’ve come to disaster? We all have a strange friendship with risk. We crave its thrill-who doesn’t want to edge a little closer to the red line where the adrenal gland squeezes and the colors grow brighter? Yet we rarely understand how close we’ve skirted that line, or what’s on the other side. Accidents? Those happen to the other guy. Nobody ever laces up his shoes thinking he’ll lead off the Ten O’Clock News.

Does that make us all irresponsible?

So now you’re Michael LeMaitre, toeing the starting line last July 4. You haven’t been up the mountain, and you’re a little nervous. Then you look up and you see the peak, so close you can almost reach and tap its summit. It’s just three measly miles, round-trip! Straight up and down again, with hundreds of new best friends! You’ve been through so much more than this. Take it slow, you think, and you’ll be fine.

Honestly-if you were Michael LeMaitre at the starting line, what would you do?

The morning I left Seward, I dragged my luggage into the hotel parking lot. The previous day’s bright, smiling sun was gone. The rain had returned, and with it a shivery dishrag bleakness. In the harbor the season’s last tourists milled about wearing crabbing gear, waiting for their tour boat to depart.

As I opened the trunk, the skies across Resurrection Bay split open. Bars of Annunciation light burst across glaciers and water and shabby hotel parking lot-the kind of unrestrained, overspilling Alaskan beauty that swells your heart and also breaks it a little bit for its fleetingness, and that makes every other soggy, frigid moment here in the far north worth it.

I turned with the light and faced Mount Marathon. The mountain stood as it always did, its Egyptian bulk leaning over town-not glowering, not protective, just…indifferent. With the sunlight a clear rainbow had appeared, arcing out of dark skies and landing clearly in the thick brush a few hundred feet up its face. It was silly and maudlin to think anything of it and I knew it, and I turned away. Then I turned back and spent a long time memorizing the location, though unsure who I would tell, or what I would say.

Eventually my eyes drifted down the long, meandering ridgeline. A second rainbow had appeared, falling to earth in the undergrowth some distance away from the first. And now an unlikely third rainbow tumbled from the sky and rooted itself, bright and promising, in still another place. Then, one by one, they disappeared.

Story Update · January 21, 2016 Nearly four years have passed since Michael LeMaitre vanished from the 2012 Mount Marathon Race in Seward, Alaska, yet still no clues have emerged regarding the runner’s fate. In July 2013, LeMaitre’s widow sued the Seward Chamber of Commerce, which organizes the race, for $5 million. (Peggy LeMaitre eventually settled in October 2014 for $20,000.) Race organizers instituted a number of new safety measures in 2013, including mandatory signed statements from runners that they’ve completed training runs on the course, a one-hour time limit for racers to reach the summit, and sweeps of the mountain by volunteers after each wave of the race. “It was a rough couple of years,” says Flip Foldager, who retired from the race’s organizing committee in 2015. “We organizers probably put more weight on our own shoulders than the public did. It’s extremely unfortunate that this ever happened and hopefully our safeguards will make sure it never does again.” Despite the tragedy, the Mount Marathon Race continues to draw an increasingly competitive field. Last year, on the event’s 100th running, pro Spanish trail runner Kilian Jornet and his girlfriend Emelie Forsberg, a Swedish pro trail runner, set new male and female course records, running 41:48 and 47:48, respectively. LeMaitre’s disappearance, however, will forever be ingrained in the event’s history. “It’s still mind-boggling that it happened in the first place,” says Foldager. Writer Christopher Solomon thinks that sentiment is likely why the story still resonates today: “How does someone disappear during a three-mile footrace? The story touches on something that many of us have often wondered while on a hike or a long run in the woods-I wonder if I could just disappear, and never be found?”

You Might Also Like