Last barrels of Henderson-made whiskey shipped out 100 years ago

Henderson’s final barrels of Peerless whiskey produced before Prohibition were shipped off to Owensboro 100 years ago this month.

The Gleaner of July 4, 1923, described the two-week process of packing the last 5,265 barrels into boxcars.For the previous three years the whiskey had been guarded by watchmen armed with high-powered rifles and handguns. Five guards were losing their jobs.

“For the first time in 42 years Henderson has no whiskey in storage,” the story said.

I’ll return to the Peerless story toward the end of this column. First, I want to give y’all a quick rundown on the handful of distilleries that have operated locally through the years, some of which have ties not hitherto widely recognized. I’m using Spalding Trafton’s article of July 15, 1923, as a starting point, but I’m supplementing it with research I’ve gathered over the years.

According to E.L. Starling’s history “the first distillery of which anything is known was a little kettle concern for manufacturing apple and peach brandy,” which was operated by a man named Melton. It produced no more than 25 gallons annually but ceased about the time of the Civil War.

There have been other distilleries, of course, even one or two that followed the lifting of Prohibition but, for the sake of brevity, I’m going to stick to the main ones with government sanction.

By all accounts, the county’s first major distillery was built by David R. Burbank on the riverfront between Ninth and 10th streets. The city gave him a 20-year lease on the property Aug. 31, 1869. He apparently had partners: E.L. Starling, Thomas S. Knight, H. Clay Elliott, and Eleazer Burbank, according to Deed Book X, page 333, which is dated April 19, 1871. Burbank owned a third interest while the others each had a sixth.

The same document contains a detailed description of that facility. It could produce 627 gallons of whiskey per day, which was aged in a two-story brick warehouse measuring 30 by 100 feet.

Nearby was the Oakland distillery. E.L. Starling had been a partner of Burbank, and later joined with Jackson McClain to operate the Oakland distillery, which Starling’s book says was built in 1872. (Starling, however, was selling his brand of “Rose-Bud” whiskey, distilled in “pure copper,” as early as Nov. 20, 1867, according to the Evansville Daily Journal.)

By Jan. 20, 1877, when the Oakland distillery was leased to Jackson McClain and John W. Johnson, it included a wooden, two-story, 84-by-40-foot distillery building, the upper floor of which was the bonded warehouse. (It apparently slid into the river in the late 1870s during a period of high water.)

What’s interesting about that lease (at Deed Book 3, page 46) is that J.E. Withers was the general manager and bookkeeper of the Oakland distillery in 1877. I’ll be talking more about Withers in a moment.

In the Henderson Reporter of March 25, 1880, A. Shelby Winstead and Bonaparte Hill announced plans to develop a distillery in a factory building at the east end of First Street known as the Car Works. It had been built to manufacture railroad cars but never got rolling because of the Panic of 1873. Winstead and Hill added two warehouses.

“Col. Winstead has been engaged here as a wholesale liquor dealer for the past 10 or 12 years, and for 17 years preceding that time was a recognized leader as a manufacturer of fine whiskey in Daviess County.”

Winstead came to Henderson in 1870 and partnered in a distillery with his brother-in-law, Elijah W. Worsham, in 1873, according to his obituary in The Gleaner of June 9, 1912. His partnership with Hill began producing whiskey in October of 1880.

Hill withdrew from the company in 1891 but Winstead reincorporated and kept churning out “Silk Velvet.” By 1909, however, the owners were thinking about using the building to manufacture automobiles.

Local life: After nearly 150 years, the parties are still going strong at this local business

All that’s left of the Winstead distillery is Winstead Avenue at the end of First Street, which originally was the entrance to the plant.

The summer of 1881 saw two more distilleries open here. One was Withers, Dade & Co., which along with J.E. Withers had H.F. Dade and Capt. Charles G. Perkins as partners. It occupied 5.64 acres on the river, roughly near the end of Rooney Drive.

Their brand was “Old Henderson County Whiskey,” according to the 1889-90 city directory. It was called the Pilgrimage Distilling Co. toward the end of its life, according to pre-pro.com, a website specializing in information about distilleries that predated Prohibition.

Owen Long, professor of business and economics at Kentucky Wesleyan College in Owensboro, wrote a series of historical articles under the pen name of Colonel Kaintuck for The Gleaner’s special edition of June 24, 1960. He wrote that the distillery was destroyed by fire; that possibly was in 1888, according to pre-pro.com.

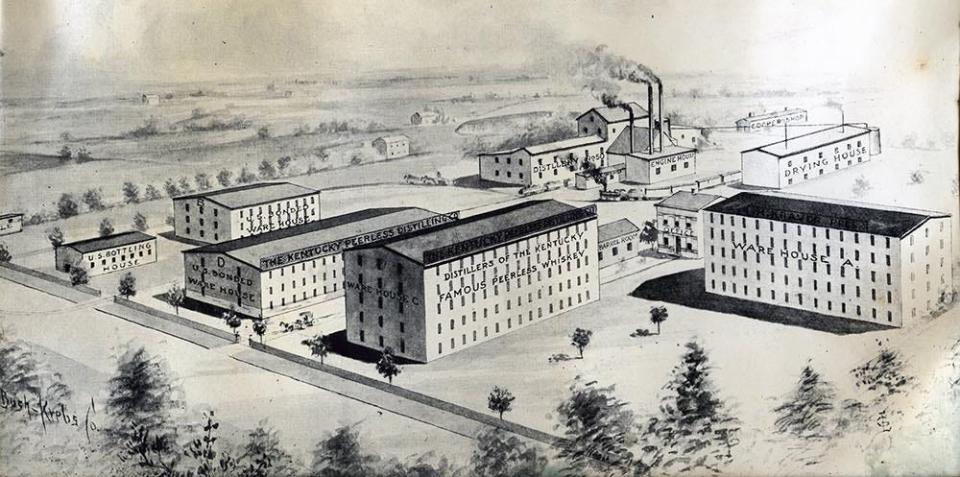

Which leaves us with Henderson County’s biggest and longest lasting distillery, which was founded by Elijah W. Worsham and J.B. Johnston. They developed land on McKinley Street near the corner of Garfield Avenue but Johnston left the partnership in 1887.

Henry Kraver, who had multiple other business interests, acquired the distillery in 1889. “He made many improvements in the matter of machinery and greatly increased the output,” according to Long.

The deed to Kraver took pains to specify that the sale included all rights to “Peerless,” the name of the distillery’s top brand. Kraver maintained the Worsham company name until 1910, when he changed it to the Kentucky Peerless Distilling Co.

By that time, multiple states across the nation had instituted Prohibition and distillers could see the jug was running dry. Kraver sped up production to squeeze as much whiskey out of the plant as possible before the federal government ceased whiskey production as part of the war effort.

The Gleaner of Aug. 21, 1917, reported it was running day and night and turning out 200 barrels daily to meet the demand. Orders flooded in after the government announced a shutdown deadline of Sept. 8. The distillery produced 23,200 barrels in 1917.

Closure of the distillery was a hard hit for the 85 employees – and for farmers who had grown accustomed to fattening their hogs on slop left over from the distilling process.

The Gleaner of Nov. 30, 1924, reported the distillery’s equipment was being packed onto 30 rail cars and would soon go to the United Distilleries Co. of Vancouver, British Columbia. By 1930 the buildings were gone.

75 YEARS AGO

The community campaign to raise money to buy what eventually became Methodist Hospital from the federal government was getting under way, according to The Gleaner of July 8, 1948.

The newspaper listed the first dozen contributors – as well as all subsequent donors.

The Gleaner of Nov. 13, 1951, says 657 persons made pledges and 625 had paid in full as of that time. The hospital cost about $113,000, with the city and county governments assuming about $40,000 of the outstanding debt. The rest was raised privately.

The hospital board ordered a bronze plaque with the names of all donors.

50 YEARS AGO

Two people were killed in the crash of a small plane on Slim Island at the Henderson-Union county line, according to The Gleaner of July 15, 1973.

The victims were pilot Willis Berry, 50, of New York and Sally Pizzatola, 37, of Oakland, New Jersey, according to the Evansville Press of July 16. They were en route from Morristown, New Jersey, to Springfield, Missouri.

Federal officials said there was a good chance the plane disintegrated after flying into a thunderstorm. There was no evidence it had been struck by lightning, but debris was scattered over a three- or four-mile area.

Slim Island is located about seven miles southwest of Mount Vernon, Indiana.

25 YEARS AGO

The renovation of what originally was the Soaper Hotel when it opened in late 1924 was unveiled in The Gleaner of July 12, 1998.

For decades the six-story building at Second and Main streets was a cornerstone of the downtown, but the years had started to take a toll.

“It closed as a hotel in the early 1980s,” according to Chuck Stinnett’s article, “and commercial tenants on the lower floors became increasingly scarce; pigeons began to occupy the upper stories. By the early 1990s its future was much in doubt.”

Attorney Ron Sheffer and contractor Don Peters teamed up to buy the building from Lambo Farmer and in 1996 “he gave us a fair price,” Sheffer said.

The job, according to Stinnett, included “gutting every floor, replacing every window, installing new heating and air conditioning equipment and a new elevator.”

The exterior was cleaned and repaired and “probably the most expensive fire escape in the state of Kentucky” was installed at a cost of $150,000, Sheffer said.

Readers of The Gleaner can reach Frank Boyett at YesNews42@yahoo.com or on Twitter at @BoyettFrank.

This article originally appeared on Henderson Gleaner: Last barrels of Henderson-made whiskey shipped out 100 years ago