How Larry Doby helped integrate Major League Baseball weeks after Jackie Robinson’s historic signing

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

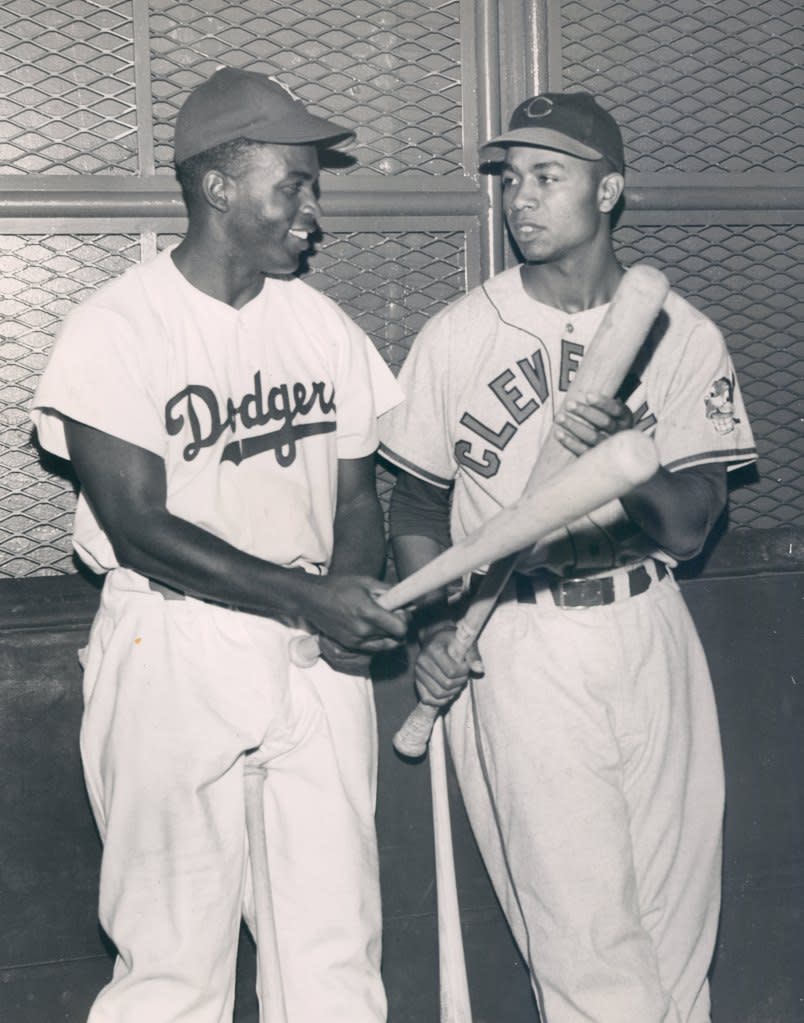

On April 15, 1947, Jackie Robinson made history when he signed onto the National League’s Brooklyn Dodgers, becoming the first African American to play in Major League Baseball (MLB).

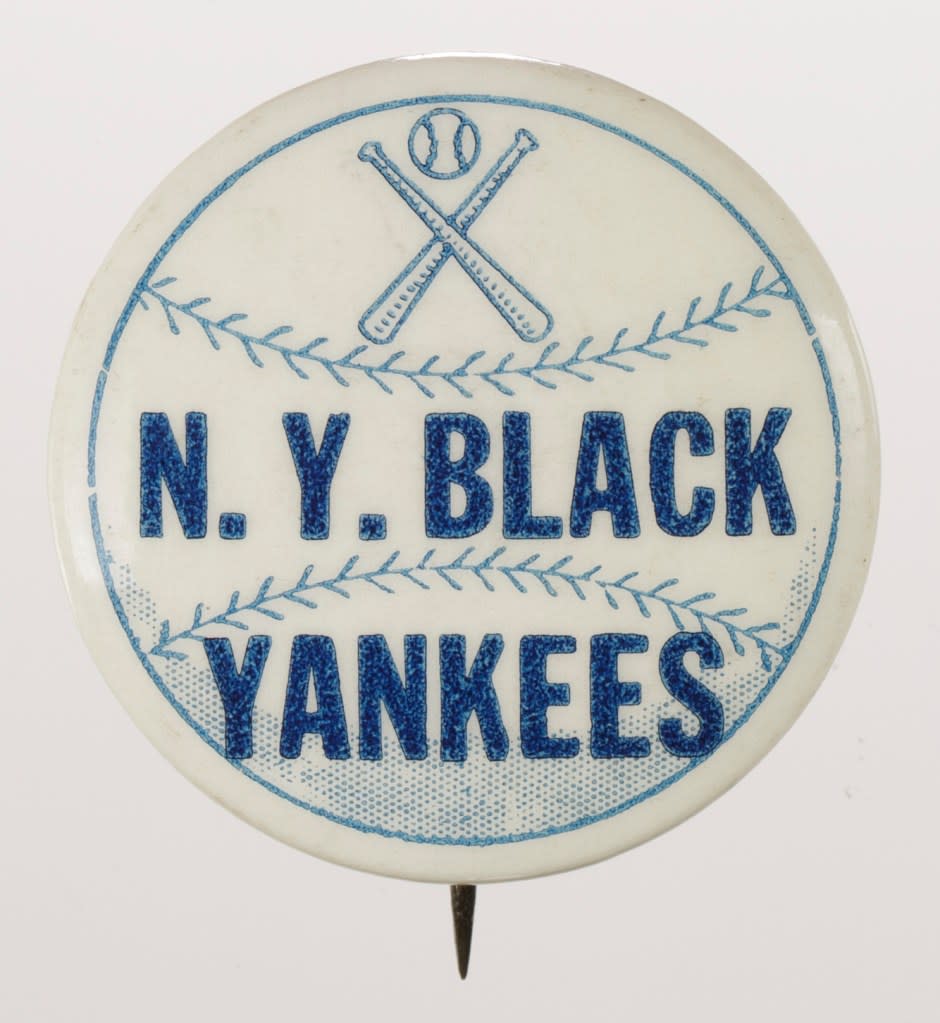

Just six weeks later, Larry Doby, a 23-year-old from Paterson, NJ, left the Newark Eagles in the Negro National League to join the Cleveland Indians and become the first ever Black player in the American League.

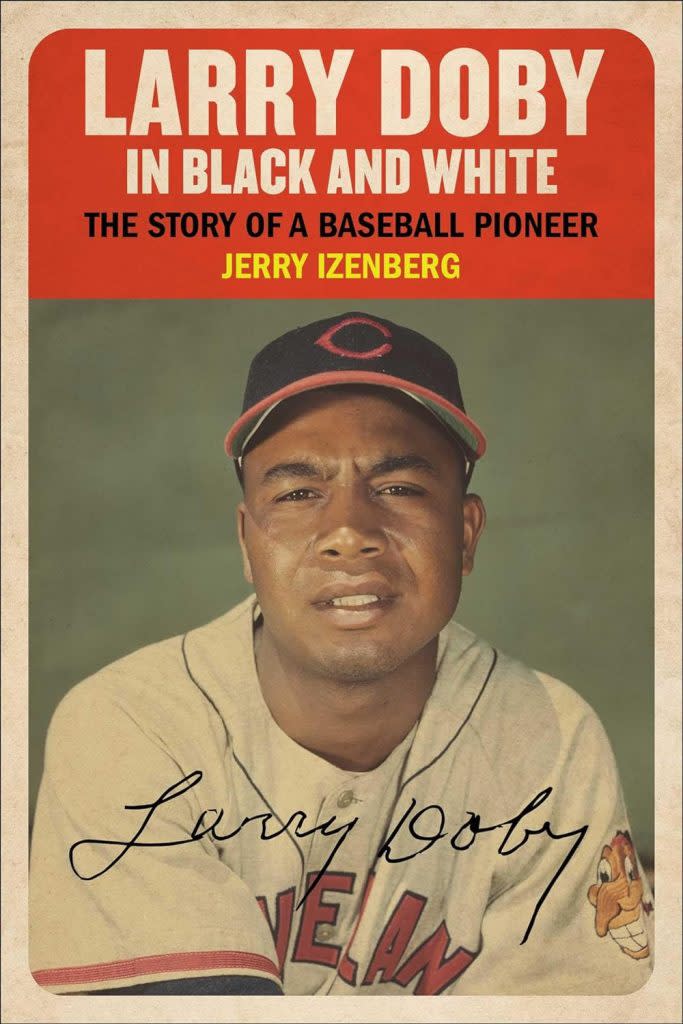

But if he thought Robinson breaking through the color barrier would make things easier, he was wrong, as Jerry Izenberg explains in “Larry Doby In Black and White: The Story of a Baseball Pioneer” (Sports Publishing).

When Doby first met his new teammates, the welcome was anything but warm. “I walked down that line, stuck out my hand, and very few hands came back in return,” he recalls.

“Most of the ones that did were cold-fish handshakes — along with a look that said, ‘You don’t belong here.’ ”

But he was philosophical.

“Jackie got all the credit for putting up with the racists’ crap and abuse. He was the first,” Doby says in the book. “But the crap I took was just as bad.

“Nobody said, ‘We’re going to be nice to the second Black.’ ”

Born in Camden, SC, in 1923, Larry Doby was the son of a semiprofessional baseball player, David Doby, who moved north to New Jersey with his mother, Etta, after his father drowned when he was 6.

At school, Doby excelled at baseball, basketball and football, winning an athletic scholarship to Long Island University. Indeed, Doby’s sporting prowess was such that he achieved celebrity status at Paterson’s Eastside HS. Everyone had his back.

When the school football team were invited to play segregated high school bowl games in Florida, the team voted to stay home rather than play without Doby, the only Black player in their line-up.

After playing for the Newark Eagles, and time in the military, Doby got his shot at the big time, signing for the Cleveland Indians in 1947.

But unlike Robinson in Brooklyn, Doby’s situation in Cleveland was markedly different.

Still schools were segregated and restaurants either refused to serve Blacks or charged a premium. Movie theaters made Black filmgoers sit in the balcony while amusement parks denied them entry.

Baseball was no different.

Doby had beer bottles thrown at him during games down South and had tobacco juice spat in his face by a Philadelphia Athletics infielder.

In stadiums in Washington and St. Louis, meanwhile, Doby had to enter via a separate entrance to his teammates. It only spurred him on.

“I always hit well in Washington and St. Louis,” he said. “I saw them out in the Jim Crow seats. I felt like a high school quarterback with his own 5,000 cheerleaders . . . And I will tell you they made some noise. “When I hit a home run, their sound was deafening.”

Unlike Robinson, Doby never enjoyed the same support networks. Even at Spring training camps, he sat in the team bus while colleagues ate in whites-only restaurants.

For Izenberg, a long-time friend of Doby’s, the way he handled himself in the face of prejudice was extraordinary. “I would ask myself — but never him — How could he keep from hating,” he writes.

“I know that had it been me, I could not.”

That Doby stuck it out was down to the man who signed him for the Indians, club owner Bill Veeck.

When Veeck took Doby out of the Negro National League, it was the start of a lifelong friendship between the two. Often, Veeck made surprise visits to whatever city the Indians were playing in, just to check up on Doby.

Certainly, Veeck came under fire for signing him.

Hall of Famer Rogers Hornsby, for instance, was livid. “Bill Veeck did the Negro race no favors when he signed Larry Doby to a Cleveland contract,” he said at the time. “If he were white, he wouldn’t be considered good enough to play with a semipro club.”

Hornsby was proved emphatically wrong.

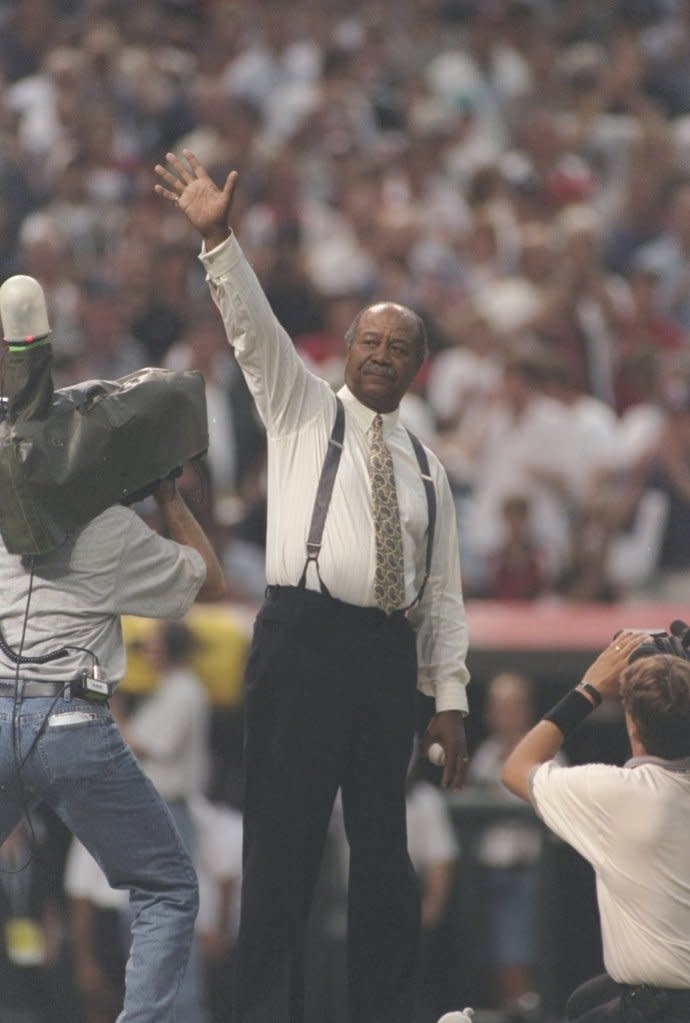

The year after joining the Indians, Doby became the first black player to play and win a World Series, and the first to hit a home run in the contest. In 1952, he led the American League in home runs — the first Black player to do so — and would become a seven-time All-Star.

When he retired, Doby became the American League’s first black manager, taking charge of the Detroit Tigers in 1979. In 1998, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Larry Doby died in 2003 after a long battle with cancer, almost two years to the day he lost his wife of 55 years, Helyn, to the same disease.

The praise was fulsome.

President George W. Bush called Doby’s influence “profound” while MLB Commissioner Bud Selig said the veteran slugger “endured the pain of being a pioneer with grace, dignity, and determination.”

Later, on the anniversary of his 100th birthday, Larry Doby was posthumously awarded a Congressional Gold Medal.

For Izenberg, it was long-overdue recognition, even if Larry might have regarded it as ridiculous.

“Looking back,” he writes, “Larry was a hero to everyone except himself.”