How Kristine Tompkins Helped Conserve 15 Million Acres in Patagonia

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

This article originally appeared on Outside

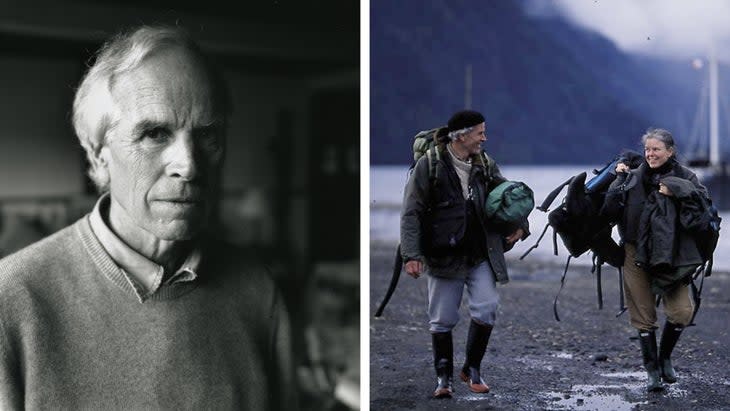

In the early 1990s, Kristine McDivitt, then the CEO of Patagonia, was at a cafe in El Calafate, Argentina, when a man named Doug Tompkins sat down next to her. "Hey, kid, how ya doing?" he asked. Doug was the best friend and climbing buddy of her boss, Yvon Chouinard, and he was known as a brilliant, arrogant bon vivant. In 1964, Doug had cofounded the North Face with his first wife, Susie Tompkins Buell. Seven years later, the two started another clothing company, Esprit. After cashing out, he moved to Chile to live alone in a small cabin.

Kristine, a free-spirited California girl who had worked her way up the ladder at Patagonia after an entry-level, two-dollar-an-hour "assistant packing" job in her teens, knew Doug's reputation. So when he tried to convince her to stay in South America with him, she demurred. (She also happened to be engaged to another man at the time.) But he was persistent. Months later, a five-day visit to Chile to see the farm Doug had purchased at the edge of a fjord turned into five weeks. Finally, Kristine returned to the States, "blew up her personal life," and never looked back--by 1993 she had quit her job, married Doug, and moved into his cabin.

For the next two decades, the pair lived between remote homes in Chile and Argentina, only occasionally returning to California. They had a grand plan: buy and protect as much land threatened by logging and overgrazing as possible. Eventually, through a series of nonprofits run by the Tompkinses, the couple purchased hundreds of thousands of acres from ranchers and absentee landowners. Their fairy-tale life ended in tragedy in 2015, when Doug died in a kayaking accident in Chile at 72. Wracked with grief, Kristine was left alone at the helm of Tompkins Conservation, which was on the cusp of making the largest private land donation in history, to take the form of numerous national parks granted to the governments of Chile and Argentina.

Who better to capture this epic saga of love and loss on film than the Oscar-winning couple of Elizabeth Chai Vasarhelyi and Jimmy Chin? Their new documentary, Wild Life, follows Kristine Tompkins's trajectory from barefoot Southern California girl to CEO of one of the most influential outdoor brands in the country to champion of conservation. The film will debut in select theaters starting April 14 and will be available to stream on May 26 on Disney+.

Chin met the Tompkinses through Chouinard and Rick Ridgeway, a climber and former Patagonia vice president. "Doug, Yvon, and Rick have all been heroes to me since I started out as a young dirtbag climber and photographer living in Yosemite," Chin said in an email. And after spending time with Kristine, he "quickly learned that she is a force of nature, an incredible human being. So of course, taking on this film was something deeply personal to me."

Before Doug died, Chin had visited the couple in South America and shot footage of them, noodling on the notion of making a film. After the kayaking accident, he and Vasarhelyi approached Kristine about putting together a movie of her life. "It took me a while to think that a film like this should be made," said Kristine, adding that she only gave her approval because she thought it would be good for encouraging conservation efforts. "I decided if I was going to do it, I would do it only with Jimmy and Chai. They are extraordinary filmmakers and trusted friends."

Wild Life delves into the Tompkinses' years of joy and struggle and the aftermath of the tragedy, as told through intimate interviews with Kristine and a close circle of lifelong companions. Chin's signature stunning photography of Chile and Argentina is intercut with 1960s footage of America's original climbing, skiing, and surfing dirtbag royalty: Kristine singing the Beach Boys' "California Girls"; the Grateful Dead playing at the opening of the first North Face store; Chouinard, Doug, and their funhog crew unfurling a flag after their historic ascent of Fitz Roy. The clips add levity and also bring into focus that, even before they were a couple, the Tompkinses were fundamental players in the creation myth of modern American outdoor culture.

It's clear that Doug and Kristine were soulmates. Yet they were also intense overachievers committed to conservation work in countries that were often suspicious of and hostile toward their efforts--some Chileans, for example, thought that the couple's real aim was to populate their land with American bison. The pair rarely had time to explore together. In the film, Kristine sets out to climb a 7,500-foot peak in Patagonia's Chacabuco Valley that her husband and Chouinard first summited in 2009. Doug dubbed the peak Cerro Kristine. Chouinard and Ridgeway--both were on the kayaking expedition that killed Doug--accompany Kristine on her journey to reach the summit, along with Chin and professional rock climber Timmy O'Neill. "Why did we never climb our mountain together?" Kristine asks the clouds as she stands alone, looking out over Patagonia National Park.

The documentary is a testament to fierce love and how its power can serve a greater purpose. "There was a deep, deep union and devotion to each other, and they came together with a common vision," says friend and filmmaker Edgar Boyle in Wild Life. But the grief that resulted when that union was severed by tragedy is difficult to watch. At one point, Kristine recounts, while flying with Doug's remains to his final resting place near their home in the Chacabuco Valley, she carved their names in the coffin with a small knife. "Doug's death was an amputation," Kristine told me. "I took some long walks by myself and was never sure I'd turn around and walk back."

The only way forward was to dive even further into her conservation work. With the help of a roughly 300-person staff at Tompkins Conservation, she exceeded her late husband's dream of creating 12 national parks. The current count: 15, along with two marine parks and a total of 14.8 million protected acres in Chile and Argentina--an area roughly the size of West Virginia. Those numbers keep expanding, along with Kristine's seemingly endless supply of energy to continue the work she started with her husband. "I carry Doug around in my pocket. If I get really stuck on something, I simply ask: 'What would you do?' I am just grateful that we have this marriage," she said, still speaking of their union in the present tense. "It's given me unbelievable strength."

Kristine is still the president of Tompkins Conservation, but she has relinquished day-to-day operations to focus primarily on strategy. In late February, she met with Chilean president Gabriel Boric to move forward with a proposed donation of 230,000 acres on behalf of Tompkins Conservation, with a view toward creating national park number 16 at Cape Froward, on the Brunswick Peninsula, the southernmost point of the continent. The rugged, largely unexplored region is a refuge for endangered species like the huemul deer. The proposal reclassifies state land that, if included, would make the area bigger than Grand Teton National Park. In recent years, two independent local organizations have spun off from Tompkins Conservation. Rewilding Chile and Rewilding Argentina each work in their respective countries to bring back endangered species--from the Andean condor in Patagonia National Park to the jaguar in Argentina's Ibera National Park.

"I want people to realize that this film is not about Doug and Kristine," she told me. "It's the representation of hundreds of Chileans' and Argentines' work. Mother Nature is not winning this game. We are all on the losing team, and everybody needs to join the fight."

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.