Korean War veterans who crossed paths in war connect 70 years later thanks to Wisconsin writer

They first came across each other more than 70 years ago in a short, intense encounter during the chaos of a Korean War battle.

Bert Ruechel of Wausau was a machine gunner in bloody fight that came to be known as the Battle of Bunker Hill. The hill was part of a strategic area of the United Nation's line of defense across Korea. In the late summer of 1953, the Chinese army sent in tens of thousands of soldiers to rout the Marines from the high ground. The Marines defended the area in a costly battle that lasted for weeks, repelling waves of enemy attacks time and time again.

Ruechel was in a key position in the defense, and during one heavy fight, saw another Marine "come running up through all that fire, yelling, 'Can I get in your hole?'" Reuchel said yes, then noticed the Marine was carrying a flamethrower after the man jumped in.

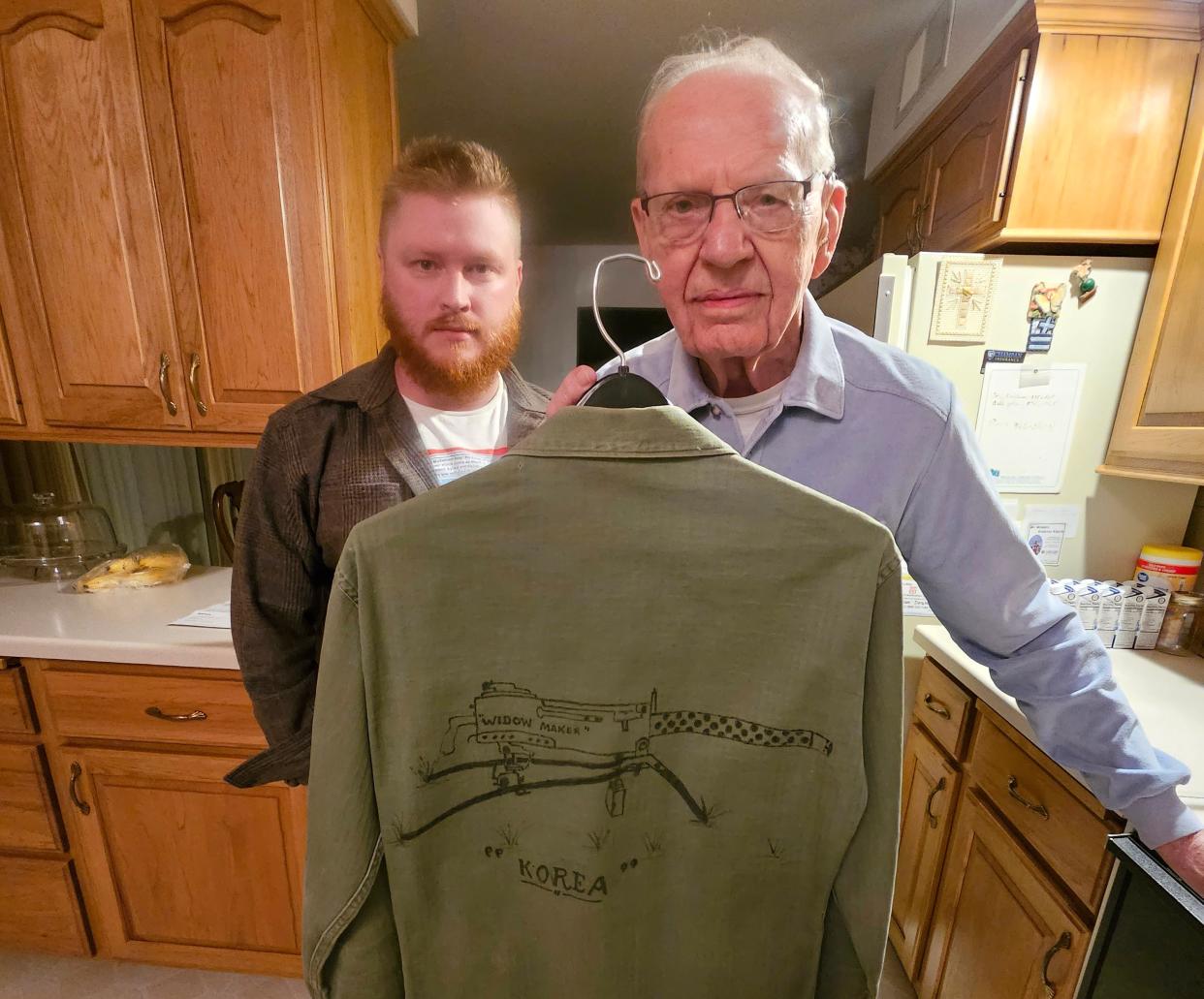

Reuchel, 93, is one of about 100 Korean War veterans from across the country who have been interviewed by Ryan Walkowski, 30, of Wittenberg. A valve technician for Midwest Valve Services in Mosinee, Walkowski works in factories such as paper mills and power plants. When he's not at work, Walkowski interviews, records and writes about Korean War veterans' wartime experiences. The project started as a Facebook page, but it quickly grew into something more lasting. Now Walkowski is in the midst of writing a book dedicated to the veterans.

He finds veterans to interview through word-of-mouth and social media. Several weeks ago he was interviewing Reuchel and showed him a video clip that he took during his interview with Joe Barna, a 93-year-old Marine veteran who lives in Freeland, Pennsylvania. As Reuchel watched the clip, it brought back the memory of the Marine with the flamethrower jumping into his hole 70 years ago.

"There were only two flamethrowers in our company," Reuchel said. "And Joe from Pennsylvania, he said he was up at the point."

"They were right down to the same platoon," Walkowski said. Making the connection between the two Marines, he said, was "an unbelievable experience. I mean, what are the chances?"

Running into each other in the heat of battle

Walkowski does not edge slowly into his projects. When he is in, he is all in. He immediately started making plans to reunite the two Marines in person in the Wausau area.

But Barna had to decline. He's involved in area veterans' groups around Freeland, and he was busy planning this year's Veterans Day events. But he said he hopes he could meet with Reuchel in the future.

Meanwhile, Walkowski plans to get Reuchel, some of Reuchel's family members and other veterans together on Nov. 13 and work out a Skype meeting with Barna.

The two veterans did not know each other during the war. Their different roles in their unit meant they didn't see each other or generally fight side-by-side.

Barna was in Reuchel's foxhole for 20 minutes, maybe half an hour, Reuchel said. It's hard for him to remember the specific details about the incident, but he remembers what happened when Barna used his flamethrower once on advancing enemy soldiers.

After he fired the flamethrower, Reuchel describes a rolling ball of flame flying downhill toward the enemy.

"He took everything out what was in front of me," Reuchel described. "With that flamethrower, nothing lives. It takes the oxygen out of the air."

After firing his weapon, Barna got out of the machine gunner's foxhole and was gone.

But then Chinese army gunners focused on the machine gun nest, and mortar shells rained down around Reuchel, some exploding just yards away. He said he could feel the concussions in his chest, through the ground.

"I said, 'Nobody is going to jump into my hole anymore. That's it,'" Reuchel said with a chuckle.

Not long after that incident, Reuchel and his fellow Marines were pulled off Bunker Hill, because too many of them had been lost in the battle. He and a few other Marines watched as other men put the dead on a truck.

"I felt sick to my stomach," Reuchel said. "I turned to these guys and said, 'You know, we could be on that truck.' They said, 'Yes we could.' ... We just stood there and watched until the trucks drove away and we couldn't see them any more."

That kind of memory "never leaves you," he said. "That just stays with your mind all the time."

Telling the stories of 'The Forgotten War'

Barna can't remember the incident where he and Reuchel shared the hole for a bit. Things like that happened too many times for him to pick out that one.

Barna wasn't trained to use a flamethrower. He had just gotten to Korea when an officer told him to take the weapon and use it. He carried a flamethrower for five months. It was a fearsome, awful weapon, he said, but effective.

"It could turn the tide of a battle," Barna said. "It was a very, very psychological weapon."

Like Reuchel, Barna has spent a lifetime dealing with the trauma of war. Talking has helped, he said, and he's written a book about his experiences in the war and life before and after. Called "God Makes Angels and Navy Corpsmen," the book is one way he honors a man who saved his life, John "Jackie" Kilmer, a Navy corpsman who was killed in battle protecting two wounded Marines. Kilmer posthumously received a Medal of Honor for his actions.

Barna, who bunked with Kilmer, said the corpsman saved his life in an earlier battle. Barna had been bayonetted in the arm by an enemy solder. He killed the soldier with a shotgun he carried along with the flamethrower, but the wound was bleeding heavily, and he could feel himself growing weaker.

Kilmer came along and told Barna that "God don't want you yet," carried him to safety, and sewed up his wound.

Barna said it's become his mission to tell Kilmer's story as many times as possible. "I need to speak for those who can't speak for themselves," he said.

Walkowski sees himself on a similar mission. He started his project to shine a light on what has become known as "The Forgotten War." But as he got to know more veterans, heard their stories, and learned about the battles and history in which they participated, the more driven he has become to get their stories preserved in a book so the veterans themselves can see it.

But first, the goal is to connect Barna and Ruechel, Walkowski said, "so they can finally chat after 72 years."

Keith Uhlig is a regional features reporter for USA TODAY NETWORK-Wisconsin based in Wausau. Contact him at 715-845-0651 or kuhlig@gannett.com. Follow him at @UhligK on X, formerly Twitter, and Instagram or on Facebook.

This article originally appeared on Green Bay Press-Gazette: Korean War vets reunited after crossing paths in battle 70 years ago