Kohanaiki: Where the Mega-Rich Hide Away on Hawai'i

On a misty day in March, I found myself riding shotgun in a golf cart around the Kohanaiki private club with my mom, a plastic cup of expensive Cabernet in one hand and a doggie bag of marlin jerky in the other, puttering past ancient Hawai’ian stone altars and bespoke villas on our way to the 11th hole. Maybe this is what being wealthy feels like, I thought for the fifth time that morning. As we raided the golf course’s “comfort stations”—each a cornucopia of frozen Mai Tais and potato chips and goat cheese and ice cream sandwiches—I couldn’t help but feel a little unease: I was anticipating getting in trouble, having a “You stole Fizzy Lifting Drinks!” moment when the time came to finally check out of the resort. But that’s some poor-people shit. It’s impossible to get into trouble in a place that was made for you to have everything you want.

The Kohanaiki club isn’t a place that you can just show up and hang out in: It’s a 450-acre patch of land on the Kona Coast of Hawai’i, the Big Island where the richest of the rich—literally billionaires, as they claim—come to live in what essentially amounts to a luxury commune. A small number of them opt to purchase memberships that entitle them to the club’s selection of timeshare homes. There are others like it, including the exclusive Kukio and Hualalai clubs 10 miles north along the coast, but Kohanaiki takes on a much more casual affect than those white-sand fortresses. Here, the land itself, with its harsh wells of volcanic rock and more than 200 anchialine ponds, intrudes upon the illusion, and the developers pride themselves on not blasting and flattening them to oblivion for the sake of curb appeal.

Every detail about this place, from the golf carts to the cheese to those meticulously preserved Hawai’ian altars and lava flows, generates a sort of free-form pleasure—whether of the material, sensory, or moral variety. It was easy to be seduced, to just give in to this notion of an ethical capitalist utopia while picking beef out of your teeth while watching the sun set over the Pacific. But, because I am a killjoy in all things and also not a billionaire, a question continued to nag at me over my four days at Kohanaiki. While initially sent to cover their in-house craft-beer program, I had to wonder: To what degree can a luxury community serve those who exist along its edges, and what could they tell us about what it meant to have incredible wealth in 2018?

I started by looking into the resort’s past, and what existed here before capital sculpted it out of the rock. Reggie Lee, a Kohanaiki staff member who grew up in the area, gave me some perspective. It was “just lava fields and goats,” he told me, with surfers and visitors driving all over the land in Jeeps and dropping garbage everywhere. Now the beachfront is maintained jointly by the club and Hawaii County, as part of a compromise struck with community activists for the development to be approved. In the end, the developer acquiesced to the community activists’ demands to preserve the area’s cultural and environmental features. In exchange, they received the right to build the luxury community, now valued at over $1.3 billion. About 100 of the club’s 450 acres are allocated for public use.

The club is proud of this story, which many of the staff repeated to me over the course of my visit. Kohanaiki members pay into this effort as part of their membership dues: It’s the fantasy of public-infrastructure renewal funded by billionaires that is the stuff of both left- and right-wing dreams. And the members are duly rewarded for their good works.

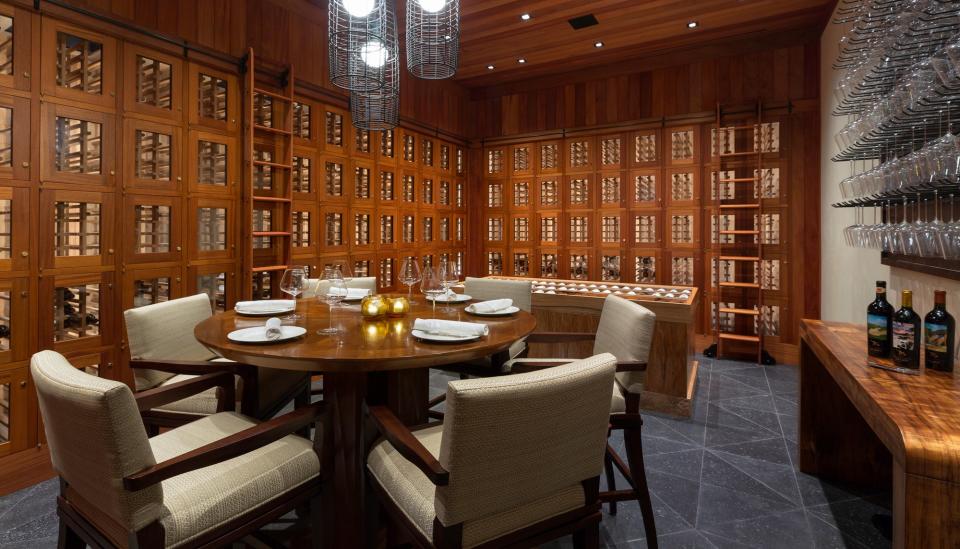

When I got to our expansive three-bedroom manor—the hale, in local parlance—I poked my nose in every nook and drawer like a good Asian, uncovering expensive cookware, tampons, red-wine-stain remover, and a freezer drawer full of Häagen-Dazs ice cream bars (!!!). The sounds of ukulele and yacht rock filled the air while a gigantic flat-screen television silently displayed a Lakers game in the living room. I left in search of people and found myself in the Clubhouse, the 67,000-square-foot centerpiece of the campus. The space felt like a child’s rendering of their dream house, complete with an audacious arrangement of video-game rooms; a bowling alley; a 21-seat movie theater set with hot dogs, candy, and popcorn; a pool; various spa and fitness centers; and a full-service restaurant. The basement’s atrium featured a museum-like display of Hawaiian crafts and books among all the residents’ personal wine lockers. I was free to indulge in any and all of it, for as long as I wanted. I couldn’t help thinking of my past struggles to seek out public spaces free from the obligation to spend money to justify my existence. Here, you pay up front for the privilege of space, so little transactions don’t matter.

At the restaurant and in the little shops at the Clubhouse, there was no tipping, no cash registers, no indignity of pulling out a wallet. The concept of money feels more distant here, without constant reminders of how much things cost, and yet it’s still everywhere, soaked into the walls and into the ever-present glow of deservingness hovering over anyone who is used to being invited to such things. In this context, cash seems to take on a feeling of obscenity: Why mess around with small bills when a phone call can arrange basketball tickets or a handshake over lunch can signify an exchange of millions of dollars? Without having to worry about money, everything expands. Go ahead and take all the chips you want.

Kohanaiki’s team know that this is a central part of the appeal. As Kohanaiki CEO Joe Root boasts in an interview with Bloomberg, "Our philosophy on food and beverage is to pretty much get people whatever they want, wherever they want it, whenever they want it.” This applies whether you want a glass of a rare wine with your dinner or if you’d prefer last month’s sushi-roll special to tonight’s. No wonder, as multiple people told me, no one really leaves the complex. It seems insane to want to rip yourself away from this sense of abundance and devotion, to re-enter the debased reality where you have to stand in line or order from a menu that might not have exactly what you want. When I spoke to Kohanaiki’s executive chef, Patrick Heymann, he confirmed Root’s philosophy with a grin: “I always say the answer is ‘Yes.’ Now, what’s the question?” It suffices to say that the restaurants here don’t make that much of a profit—not that it matters.

As I spoke to the staff, I increasingly found it hard to reconcile that philosophy with Kohanaiki’s sustainability narrative. We know that the American lifestyle takes up more natural resources than that of any other country in the world. So does it really matter how many anchialine ponds and reefs are preserved when companies like Kukio and Kohanaiki are racking up food miles by flying in fresh uni from Japan or live Maine lobsters at the behest of their clients’ whims? Does the solar-powered reverse-osmosis water-filtration system, which supplies the golf course with the million gallons of water it needs every day, offset the outsize amount of human and material resources devoted to the happiness of each resident here? Perhaps it’s ridiculous to consider this in terms of an ethical balance, but the “intelligent sustainability” of Kohanaiki is clearly a major part of their image; the property begs the question.

These questions aren’t Kohanaiki’s to bear alone: They’re ingrained in American culture writ large, but they’re inflated to the extreme here. Maybe the good feeling of funding a public beach with functional bathrooms while you get a full-body coconut scrub in your private clubhouse/dream fort is an inevitable symptom of the growing global wealth gap. Because it’s harder to ignore, no matter how insulated your community is, so you feel the urge to pay for your indulgences, to justify your lifestyle with passive good works. It’s the same late-capitalist tingle you might get purchasing a pair of TOMS shoes. You give up a little, pay a little extra, to feel good without having to do any of the big things that get at the root of the problem. When you start asking why local Hawai’ians didn’t have the capital to take care of their own land, or why all of my neighbors in this luxury commune are white, things get a little more uncomfortable. But discomfort isn’t what you’re paying for, and it’s one of the few things the staff doesn’t want to offer you.

At the beach, I talked to Gary Eoff, a transplant from California and practitioner of traditional Hawaiian weaving and crafts, as well as Lee, about all of this. As one of the original members of the Kohanaiki 'ohana, or "family," Eoff describes himself as a “lead radical dude” who fought development of the area since the 1980s, back when the activists were just a bunch of surfers hoping to keep their spot free and clear. We all spoke while eating Gary’s rendition of a vegan poke and sitting in the public halau, an enormous pitched structure of wood and plant fibers bound together in the traditional way. This halau, built through a joint effort between community activists, the county, and the club, is a space where the two men and other community members hold classes for local kids on crafting, oral history, celestial navigation, and ecology.

Eoff admitted that while his cooperation with the club earned him a degree of scorn among some of his activist peers, “we won.” As part of their agreement, the developers granted the public 100 acres of shoreline in perpetuity, to be managed jointly. Eoff and Lee showed me what the 'ohana built in the ensuing years, taking me through rows of taro plants and ipu squash vines in the canoe garden while little brown francolin birds scattered at our advance. The cordage plants were the same types that Lee’s mother, Elizabeth, used in her traditional weaving. The two told me about their 20-year plan to save the shoreline from coastal erosion due to climate change by planting coconut trees and reconstructing the reef. Eoff didn’t really give a fuck about the golf course, or the audacious lifestyles of the people in the club. “Money is everything,” he said. You need it to buy those coconut trees, to build this halau, to clean up the beach. The moral quandaries that tangled my thoughts quieted.

Maybe it’s easier to get people with privilege to help others when their rewards are so pleasing—when they can play on it, sleep on it, drink it, taste it. And, though the charity enables a lifestyle that keeps people with privilege in their personal pleasure domes, perhaps it’s worth it when it helps people like the Kohanaiki 'ohana work for their communities and make space for colonized people to maintain a connection to their history. So what if passively funding the public beach helps the super-rich sleep better at night? It’s not like you can take all of those years of colonialism back, right? But possibly, this failure of my imagination is also a symptom. Back in the halau, Eoff looked at me point blank and said, “You know, eventually the golf course may not be here anymore.” Lee nodded in assent. Looking to the ways the elders did things seems more and more important these days, he said. The way things were going, the ocean will likely advance and swallow up the land, the anchialine ponds, the gardens, and the lovely public bathrooms, lapping up the welcome mats of the houses further inland. Until then, the kids were going to learn how to navigate using the stars.