What to Know About Voter Suppression

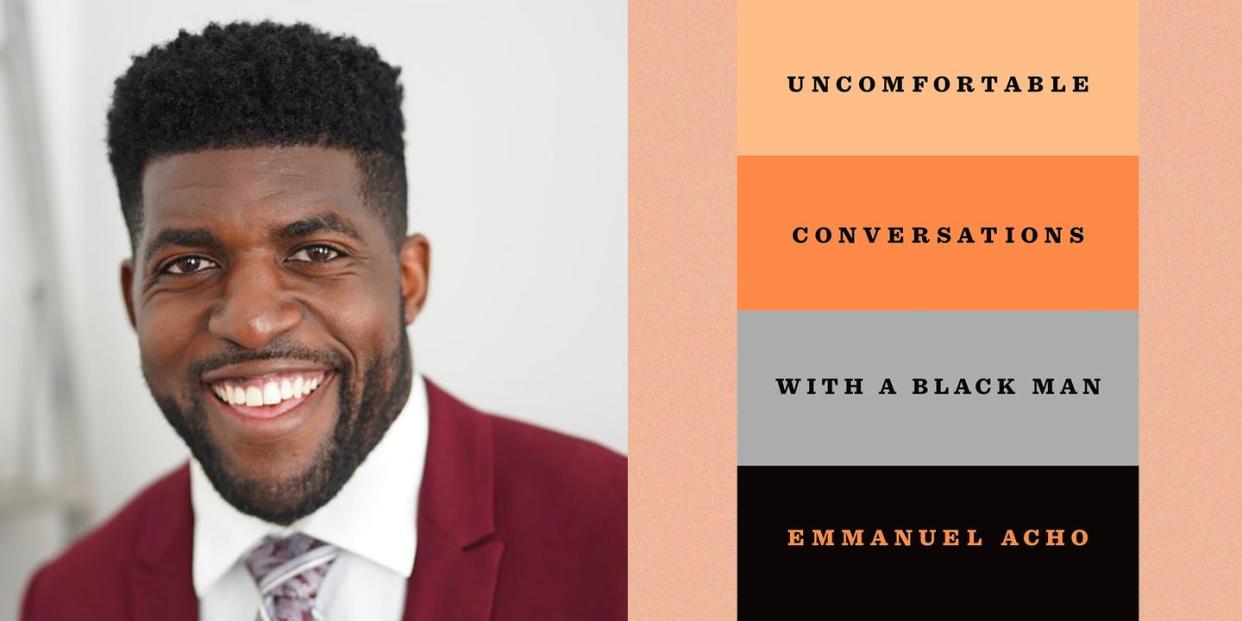

Emmanuel Acho is a former NFL linebacker and the author of the incisive book Uncomfortable Conversations With a Black Man, which was selected as one of Oprah's Favorite Things this year.

Acho was also a recent guest on Oprah's Apple TV+ show, The Oprah Conversation.

Below, find an exclusive excerpt from Acho's book about voter suppression—what it's like to experience it, why it exists, and how to fix it.

Good people, let me remind you that I was born and raised in Dallas, Texas. During the 2016 election, I was living it up in my hometown and looking for a polling station. Wouldn’t you know it, there was one at this church right by my crib. This was my first time voting in Texas (I had been in Cleveland for the last election, playing for the Browns). That is to say, I didn’t know what to expect and was thinking that the poll station might have a crazy line. But when I pulled up to the church, there was nobody there except six or seven poll workers. I waltzed right inside, said hi to the nice white staffers, filled out my little ballot, submitted it, and waltzed my smiling self right back out. The whole thing took maybe three and a half minutes, hellos and goodbyes included.

Now compare that to the 2018 midterms. At that time, I was living in Austin, Texas. My house was in a gentrifying area on the east side of town, and my closest polling station ended up being a Fiesta grocery store. I don’t know if any of you have ever been to a Fiesta, but it’s a popular chain in heavily Hispanic neighborhoods down here.

During those 2018 primaries, I pulled up to Fiesta with the confidence of a dude who’d last voted in an affluent neighborhood, thinking I was going to walk my happy little butt into another polling station and zippety-do-dah right out. But when I turned the corner to park, I saw a line of at least two hundred people. Man, I thought, what is this? I walked inside to investigate and saw the line snaking around the store and back outside. I couldn’t believe it. “Is this the line to vote,” I asked, “or are they giving out free trips to the Bahamas?” They were like, “No, no, no, this is the line to vote.”

I was tempted to leave. I had a flight to catch; I didn’t have two and a half hours to wait in line. But there was this sweet old Black woman in front of me, and she said, “You’d better stay here, son. Remember all we went through to vote.” I looked at her. I waited in that line.

Now picture this. While I was breezing through a polling station in 2016, not far away in Fort Worth, Texas, a woman named Crystal Mason walked to her local station to do what that old woman in Austin had reminded me to stay for. Mason, a mother of three, might not have voted had her mother not convinced her that it would set a good example for her kids. Mason trooped down to her local polling station, and to her surprise, her name wasn’t registered on the voting rolls. Determined, she cast a provisional ballot, meant to be approved pending further checks. Mason was a formerly incarcerated person and as it turns out missed the fine print on her ballot that read, “I understand that it is a felony of the second-degree to vote in an election for which I know I am not eligible.” Not only did Mason fail to see the words, she was also unaware of Texas’s super-strict voting laws, the ones that actually made her ineligible to vote.

Three months after she voted, she was called into a Fort Worth courthouse, handcuffed, and charged with voter fraud. A year or so later, she was convicted of fraud and sentenced to the harshest penalty possible: five years in prison. It hardly seemed a fair judgment for the small oversight of a woman and mother of three who believed she was doing her civic duty.

Is America really a democracy? The short answer is no, it’s technically a republic, or what some people term a representative democracy. Our laws are made by representatives we have chosen (in theory), who must comply with a constitution that was built (in theory) to protect the rights of the minority from the will of the majority. But the truest answer is that America has never been a republic for everyone who lives within its borders.

So we’ve got systemic racism, right? All these institutions like housing, schools, and prisons that keep disadvantaging people of color. You may have been asking yourself, If we have laws keeping these systems in place, why not just make new laws? Why not vote out racist people and practices? This chapter is about why not. There are tools, it turns out, by which (some of) those in power are still actively perpetuating racist systems and disenfranchising those who would change things—a.k.a. the voters. I call this whole situation the Fix. If we want an America that’s not fundamentally racist, we must address the Fix, like, yesterday.

Let’s Rewind

Two of the most rigged parts of our democratic system are voting and jurors. Both of these ways of participating in government have had more discrimination than we could cover in all four quarters and overtime of a tight game, so in the interest of space, I’ll focus on the long history of voter suppression of Black people, and the pernicious practice of rigging juries against Black folks (and other POC).

You might’ve heard of a little thing called the electoral college. Yes, the confounding institution that awarded the 2016 election to Donald Trump and the 2000 election to George W. Bush, despite their opponents winning the popular vote in each case. You might remember from civics class that the electoral college was created because, during the Constitutional Convention, the Founding Fathers thought ordinary Americans wouldn’t have enough information to make informed and intelligent voting decisions. While that may have been true, there was also another major factor being hashed out between those Northern and Southern delegates: what to do about five hundred thousand or so enslaved people. The result of that debate was what became known as the Three-Fifths Compromise.

Article 1, section 2 of the Constitution states: “Representatives and direct taxes shall be apportioned among the several states which may be included within this Union, according to their respective numbers, which shall be determined by adding to the whole number of free persons, including those bound to service for a term of years, and excluding Indians not taxed, three fifths of all other persons.”

In layman’s terms, the compromise counted each enslaved person as three-fifths of a human being for the purposes of taxes and representation. That agreement gave the Southern states more electoral votes than if they hadn’t been counted at all, but fewer than if Black people had been counted as a full person. And that political leverage paved the way for nine of the first twelve presidents being slave-owning Southerners. Keep in mind, those enslaved Black people couldn’t vote themselves, couldn’t own property, nor take advantage of any of the other privileges available to white men. Not only was all their labor stolen from them, their bodies were symbolically used to grant their enslavers more power. If we’re talking an electoral fix, the Three-Fifths Compromise is the ultimate.

A century on, as you know, the Thirteenth Amendment abolished slavery, which gutted the Three-Fifths Compromise. The Fourteenth Amendment then granted formerly enslaved people citizenship and gave Black people supposed “equal protection under the law,” while the Fifteenth Amendment declared, “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” So, game over? Of course not. It wasn’t long before Southern states were inventing ways to skirt the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments and keep Black people from participating in American democracy.

No better place to start than with what were called grandfather clauses. Beginning with Louisiana, seven states between the 1890s and early 1900s passed statutes that allowed any person who’d been granted the right to vote before 1867 to continue voting without the need for a literacy test, owning property, or paying a poll tax. These were called grandfather clauses because white men (remember, women were decades from being granted the right to vote) were literally grandfathered in. Since most Black people had been enslaved prior to 1867, they were denied the right to vote based on the clauses. They still had to be allowed to vote, legally, but states took care of the reality by requiring poll taxes (it’s exactly what you think: paying to enter the polls), literacy tests (reading and writing had been forbidden under slavery), property ownership, and even constitutional quizzes (how does one pass one such test when he can’t read or has never seen a source where the information is written?).

The Northern states weren’t angels, by the way. For the purpose of “healing the union” after the Civil War, they basically let the South have their way and thereby squandered all the promise of Reconstruction. The way I see it, those Northern states were the devil’s bargainers of the era: the fixers who, to ensure their own power, agreed that freedom didn’t have to mean power for Black people.

Voter suppression laws are not a bygone practice. They are in place right now, using new and refurbished tactics with the same old objective: to disenfranchise Black people. Such as in Kansas, where a Republican secretary of state, Kris Kobach, championed a law that required proof of citizen ship to vote on the pretense that non-citizens were voting illegally. That law failed because the U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals said that Kobach, a white man, “failed to prove the additional burden on voters was justified by actual evidence of fraud.” During the time the law was in effect, thirty-one thousand applicants were prevented from voting, yet the appeals court noted that no more than thirty-nine non-citizens had managed to vote in the past nineteen years.

Other states, including Arkansas, Pennsylvania, and North Carolina, have enacted voter ID laws using claims of voter ID fraud. This despite these ACLU stats: up to 25 percent of Black citizens of voting age lack government-issued ID, compared to only 8 percent of white people. Other strategies of voter suppression, a.k.a. the Fix, are state legislatures increasing or decreasing the number of polling stations in a given district, changing the times or days the stations are open, and even planting faulty machines in certain polling stations to slow them down. Another common tactic has been purging the registries of people who can vote. This is done by removing people from the voting registry who haven’t voted for a certain number of years or haven’t received a voting card mailed to their address. This more often targets Black people and poor people who have unstable housing.

And then there’s gerrymandering. This is when state redraws the boundary of a voting district to negate certain votes. Two ways to do this: One is “packing,” where voters are clustered into a district predicted to be won by an oppositional party, so the extra votes are wasted on that party. The other is “cracking,” when voters for a party are broken into multiple districts where the opposing candidate will win with a large majority, again wasting votes.

One more election Fix that’s been getting attention: preventing people who’ve been convicted of a crime from voting. The length and kinds of restriction varies from state to state, from a lifetime ban up to people being disallowed to vote while incarcerated, and including restricting their ability to vote until they’ve completed parole or paid certain fees. Barring currently or formerly incarcerated people from voting doesn’t only suppress Black voters, it targets them disproportionately, since they are overrepresented in prisons and jails.

Sometimes these tactics fail, luckily. When the Wisconsin legislature insisted on curtailing voting by mail and held voting during the pandemic this year, the thinking was that their tactics would cause a much lower voter turnout of Democratic voters (more often tied to crowded inner-city polling stations and outside-the-home work schedules) and protect a conservative Wisconsin Supreme Court spot. Their plan backfired, instead inspiring a huge turnout that helped to unseat the conservative majority. And just a few months ago, a Florida federal judge ruled that a state law requiring felons to pay any outstanding fines before registering to vote is unconstitutional.

Too often, though, voter suppression succeeds.

Would it surprise you that another part of the Fix involves our courts and, in particular, our juries? Bryan Stevenson, a man who’s dedicated his life to social justice (have you read the book or seen the movie Just Mercy?), describes American courts this way: “We have a system of justice that treats you better if you’re rich and guilty than if you’re poor and innocent.” I would add to his adjective of poor the adjective of Black.

Maybe no person knows this better than Timothy Foster, a man who in 1987 was convicted by an all-white jury in Georgia of murdering a white woman and sentenced to life in prison. Foster’s case ended up before the U.S. Supreme Court, where it was discovered that Georgia had stricken Black people from his pool of possible jurors, using a process known as peremptory strikes. The Supreme Court had ruled the selection of jurors by race to be unconstitutional just a year before Foster’s trial, so peremptory strikes had become the loophole: a playbook of race-neutral reasons given to strike a Black juror in the hope that one of those reasons will be found valid by the judge. News flash: one of those reasons is often found valid.

A little recap here. For almost a century, Black people were not allowed to legally vote, even as their bodies (three-fifths each) were used to beef up the Southern vote. Then they get the legal right to vote, only to face all kinds of nefarious tactics to keep them from it. They then face a justice system not of their peers but white people (in 2017, 71 percent of U.S. district court judges were white), who send them to prison far more often than white people. Once freed, they face yet more obstacles to vote. Should they somehow vote by accident, they face more prison—and should they not vote, well, they have little means of changing the laws and those who make them.

A lose-lose situation, whichever way you look at it. That, brothers and sisters, is the nature of the Fix.

Let’s Get Uncomfortable

Because of suppression, there are fewer polling stations in places of lower socioeconomic status, particularly liberal places in Republican states. Back when I was in Dallas, my fancy neighborhood with the breezy voting experience was also a Republican area. But in Austin, I lived in a gentrifying area that is of a historically lower socioeconomic status. What I remember from that day was that several people left the line, and if I had to guess, I’d say some of them left because they couldn’t afford to take off from work.

Voting privileges, juries: it’s a difficult conversation for anyone who counts political ideologies as an important part of their identity, because you want to believe that your party is on the up-and- up. Our democracy is supposed to be fair and impartial, but the truth is that both Republicans and Democrats engage the Fix to some degree. You don’t need to be a political scientist to see how unfair the political system has been to Black people. We must continue to bring up these tough conversations, between one another, on our social media platforms, in our newspapers, and so on.

Crystal Mason waived her right to a jury. You have to wonder, why would a Black woman in Texas waive her right to be tried by a jury of her peers? You have to wonder if it was because Mason did not believe she would get a fair trial by jury. You might wonder whether Sharen Wilson, the Republican district attorney who aggressively pursued the case, would have used peremptory strikes to ensure just that. In any case, I doubt that a fair jury, one that included Black people and other POC, would have decided to send a mother to prison for mistakenly filling out a provisional ballot. Instead of a jury, Mason’s fate was solely in the hands of District Judge Ruben Gonzalez (yes, name drops for the DA and judge), who decided that Mason should do five years’ time for overlooking some fine print.

“It doesn’t make any sense,” Mason said in an interview with The Guardian. “Why would I vote if I knew I was not eligible? What’s my intent? What was I to gain by losing my kids, losing my mom, potentially losing my house? I have so much to lose, all for casting a vote.” She appealed her sentence and was denied.

Meanwhile, in the very same county where Mason voted that year, a judge named Russ Casey pleaded guilty to turning in fake signatures to secure a place on a Texas primary ballot. His crime was not, in any way, an accident or oversight. It was a premeditated affront to our political system. Casey pleaded guilty to committing that crime, and for his guilty plea, the Texas courts sentenced him to two years in jail—then commuted his two-year prison sentence to a five-year sentence of probation. Can you believe that? A five-year sentence upheld on appeal for a Black woman versus a two-year sentence commuted into probation for a white man. The Fix was in way back when. And the Fix is in right this second.

Talk It, Walk It

Go to www.usa.gov/absentee-voting to find out about mail-in voting in your state. You can find general information as well as a link to your state’s local election office for specific rules in your state. You can also visit www.vote.org/polling-place-locator/ to find the polling stations in your state or community.

If you’re in Texas, call your elected official and demand that Crystal Mason be released from jail. If you’re elsewhere, visit the American Civil Liberties Union, which, among other things, launches legal battles against voter suppression all over the country. Their website has a whole tab of resources on the subject. While you’re there, donate some money if your means allow it.

Volunteer at a local community organization or shelter, a place where you can encounter citizens who might not be as informed on the voting process and their particular voting rights.

Help register voters, especially in areas with a high number of Black people and/or POCs and/or poor people.

Next election, work at a polling station and be as helpful as you possibly can, pointing out the fine print when necessary.

Visit the League of Women Voters (LVW) website (lwv.org) and donate to them, too. Read up on the For the People Act, and then call up your state legislators and push them to vote for it.

Visit the NAACP (naacp.org) and donate to some of their empowerment programs.

You could also sign up as a volunteer to help turn out voters.

Support Black leadership, and remember to choose your leaders critically.

Write an op-ed.

Start a GoFundMe for someone’s legal fees.

As with systemic racism, the issues are countless, but so are the ways to help.

One more note: don’t forget about local elections. State legislatures have a huge influence on what you can and can’t do where you live; the mayor approves the city budget on things like police or school funding; your local district attorney has say over who goes to prison and who doesn’t. Local elections can even get your potholes filled, and I think we’re all anti-potholes. So do your research on the candidates just as you would for a president. Attend their speeches and debates when you can, call them out on issues of fairness and bias. Make them accountable to their records in a public forum. Also, make sure you always show up for jury duty when you’re called. If you have people of color in your life, make sure they don’t skirt jury duty either. Vote, vote, vote, vote like your life depends on it. Like our lives depend on it. They do.

Excerpted from Uncomfortable Conversations With a Black Man, Copyright © 2020 by Emmanuel Acho excerpted by permission of Flatiron Books' an Oprah Book Imprint, a division of Macmillan Publishers. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.

You Might Also Like