What to Know About Febrile Seizures

Brian Maranan Pineda

My nerves are made of steel. Sure, I worry about the usual things, but it takes a lot to really rattle me. My daughter, Simone, was a preemie, and fellow preemie parents can attest that once you've dealt with ventilators and scalp IVs, the ordinary scrapes and tumbles barely register. But one night when my daughter was 2, my parental bravado evaporated.

Simone's nose had started to run, and she'd been feverish and cranky all afternoon. The beginning of a cold, I'd figured, but soon after she settled down for the night I noticed her skin had become searingly hot. As I rummaged in the nightstand for a thermometer, I heard her make an odd noise and turned to look. Her eyes were open and glazed, and her legs were jerking. She was having a febrile seizure. Although I'd known plenty of terror during our early days in the NICU, the next few minutes were easily the most frightening of my life.

"A seizure is very scary to witness," agrees Sucheta Joshi, M.D., a pediatric neurologist at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor. "Many parents believe their child is dying." Waiting for an ambulance with Simone in my arms, that is exactly what I believed. "However, a typical -- or 'simple' -- febrile seizure does not harm the brain or development," says Dr. Joshi, who is an expert on seizures in children. In fact, febrile seizures are extremely common, especially among very young children: One in 25 kids will have one before the age of 5.

Brian Maranan Pineda

Anatomy of a Seizure

Even if you know what a seizure looks like, you may have no idea what's happening inside your baby's skull to cause it, and it certainly seems like something bad. But doctors say that in order to cause brain damage, a fever would have to be upward of 107?F, and regardless, a seizure doesn't signal that brain damage is occurring.

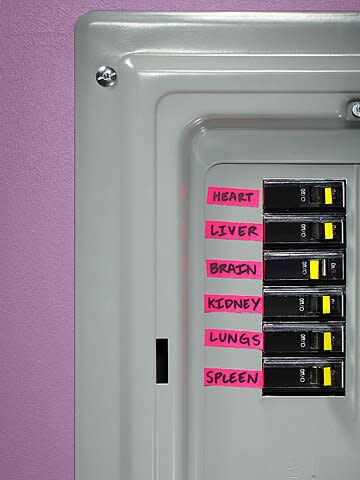

Essentially, any seizure is a surge or short circuit of electricity in the brain. Jing Kang, M.D., Ph.D., a seizure researcher at Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, suggests you think of your child's brain as a bustling city of electrical circuits: "The brain has billions of neurons creating and receiving electrical impulses. These impulses are how different parts of the brain communicate with each other. But any abnormal electrical discharge can result in a seizure."

It's not clear why seizures are more apt to occur in a young child, says Dr. Kang, "but it's likely related to the fact that the brain is growing so quickly." The amount of stimulation a brain can tolerate before a circuit overloads is called the "seizure threshold." A 3-year-old's brain is twice as active as the brain of an average adult, and with that activity comes a lower seizure threshold than that of an adult.

Recognizing the Problem

A child having a simple febrile seizure, which may also be known as a grand mal seizure, can lose consciousness (while still breathing) and then become rigid as muscles on both sides of his body contract. Often, his eyes roll upward. He may moan or grunt and lose control of his bladder. His muscles jerk rhythmically, and he may not respond to voices. I found it very frightening that my daughter's eyes were open during her seizure, but she didn't seem to be present behind them. For me, the only thing scarier was when her skin turned pale and mottled, and the area around her lips took on an alarming bluish tinge, making me think she wasn't getting any oxygen -- which prompted me to call 911. But according to Dr. Joshi, breathing irregularities are another item in the horrifying-but-expected category: Children may still be taking in air, if irregularly, and spells of seizure-induced breath-holding are usually too brief to be a serious concern. (This is reassuring, but if I had it to do over, I'd still call 911. Any kid of mine who stops breathing earns herself an ambulance ride.)

A simple febrile seizure can go on for as long as ten minutes. But most last just a few minutes, and many are over in seconds. The seconds can seem to stretch on indefinitely, or the episode may pass so quickly that you aren't sure what you saw. Once the seizure has passed, your child may seem disoriented but should return to normal within half an hour. He's likely to be exhausted as well, and this may last into the next day.

An Elusive Cause

There are so many explanations for how fever might trigger seizures that it's hard to know which is ultimately responsible. And doctors continue to study and debate why some fevers cause seizures in some children and others do not. For many years the accepted wisdom was that febrile seizures are brought on by a fast-spiking fever -- and that it is the speed of a fever's rise, not how high it rises, that causes the electrical surge in the brain. Recent research has called this notion into question, though most febrile seizures do occur while the temperature is rising -- usually in the first 24 hours of an illness.

A high temperature can itself increase "excitability" in the brain, making it more prone to electrical outbursts, and kids' brains tend to respond to illnesses with a higher temperature than do adults' brains. And neurons are more excitable when rapid breathing disrupts the balance of oxygen and carbon dioxide in the brain. Doctors are also focused now on the role of cytokines in seizures. These are a kind of protein, released by the immune system in response to illness, that both increase electrical activity between neurons and turn up our internal thermostat.

While seizures more commonly appear with a higher fever, there does not seem to be a "minimum" temperature required to trigger one. "A febrile seizure is likely caused by a combination of the rate of a fever's rise and individual susceptibility," Dr. Joshi explains. Some kids are simply more vulnerable to febrile seizures and at a higher risk of getting subsequent ones. What's more, certain viral illnesses are more likely to cause febrile seizures; roseola and ear infections seem to be the most common culprits, says Dr. Joshi. Febrile seizures are far more often the result of a virus than a bacterial infection. This could be due to the unique set of cytokines triggered by the different types of germs.

Your Next Move

Any child who has a seizure should be evaluated by a doctor, but there's no need to rush to the E.R. unless she injures herself or stops breathing while seizing or if the seizure doesn't end within 15 minutes. Call your doctor as soon as the seizure is over. You'll be asked questions to determine whether your child needs to be seen right away. Of course, given the horrifying spectacle of a seizure, it's common for parents to panic and dial 911. But in my case, by the time the paramedics arrived my daughter was no longer blue, her fever was down, her color had returned, and she was actually smiling. Simone slept through the entire exam, spent.

At the hospital or clinic, the workup will focus on finding the source of infection. Your doctor may run blood tests and take a urine sample. There's a perception that seizures are often a sign of meningitis, but this is untrue. "Simple febrile seizures are rarely caused by bacterial infections of the brain," says Dr. Joshi. The American Academy of Pediatrics recently changed its guidelines to reflect this and only recommends a post-seizure spinal tap for children who have other symptoms of meningitis (like a rash or neck stiffness), or are difficult to arouse and irritable. A spinal tap may also be considered for kids who are at increased risk because of their young age and/or because they haven't been immunized against Hib and streptococcus pneumonia. (These are the two most common causes of bacterial meningitis.)

Doctors will also do additional testing if a child's seizure lasts longer than 15 minutes or is limited to one side of the body. This is called a "complex" rather than a "simple" febrile seizure. Other causes for concern are confusion or lethargy that persists for more than an hour or two, or another seizure within 24 hours.

RELATED: The Best Way to Take a Temperature

Will It Happen Again?

About 30 percent of children who have one febrile seizure will go on to have another. Having a febrile seizure demonstrates that fever can trigger a seizure in your child and that he may be prone to them in the future, at least until he outgrows them altogether. (A subsequent seizure without fever is a different matter and merits a thorough evaluation.) "Febrile seizures occur between 6 months and 6 years of age, and should not persist beyond then," says Dr. Joshi. Recurrence is more likely if there is a family history of febrile seizures, if your child's first febrile seizure was accompanied by a relatively low temperature, or if he was under 18 months old at the time.

Perhaps the most widespread misperception is that febrile seizures cause, or indicate, epilepsy -- a neurological disorder marked by recurrent, unprovoked seizures. "A child's risk of epilepsy may double after a febrile seizure, but only from about 1 percent to 2 percent," explains Dr. Joshi. She stresses that the overall risk remains very small. What's more, the slightly higher incidence of epilepsy among kids who have had a febrile seizure could be because some of them had undiagnosed underlying epilepsy. Dr. Joshi insists that a child who has a febrile seizure is, by and large, fine. "The vast majority of children who have simple febrile seizures will not develop epilepsy."

Eager to do anything I could to prevent ever witnessing another episode, my plan was simple: I''d never let Simone's fever get out of the gate. Her fever had registered at a scorching 106?F at the time of her seizure, and I figured all I had to do was shovel in the acetaminophen at the first sign of a warmish brow. Unfortunately, my strategy has a serious flaw: "While aggressive fever control is safe, studies have shown that it won't prevent febrile seizures," says Dr. Joshi. This seems not only unfair, but extremely nonsensical. Simone + High Fever = Seizure, thus Simone - High Fever = No Seizure. The reason it doesn't work that way is (again!) unknown but may be because while medication can lower the fever, the cytokines released by the illness are still zipping around and exciting the brain.

Simone has had many fevers since that night, but thankfully no more seizures. Still, I worry every time her temperature rises. The unpredictability is daunting, but I suppose parenthood is all about learning to live with this kind of uncertainty. For now, I'll keep telling myself what Dr. Joshi told me: "Your child is fine."

What to Do During a Seizure

The main goal is to prevent your child from becoming injured while the seizure runs its course.

Do

Try to lay him on his side, ideally on a firm, flat surface, to prevent choking on saliva that collects in the mouth.

Loosen any zippers or buttons close to the neck.

Remove any obstructions, like a pacifier or food.

Note the time, and note it again when the seizure stops.

Don't

Put anything in your child's mouth. (The idea that a child can "swallow" his tongue is a myth.) Placing objects like a tongue depressor or a spoon into a child's mouth during a seizure can cause injury.

Attempt to restrain a seizing child; instead, allow the seizure to run its course.

Vaccines and Seizures

You may have heard about a connection between febrile seizures and vaccinations, specifically the combined measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccine (MMRV). Studies found that 1- to 2-year-olds who received the MMRV combination vaccine were slightly more likely to have febrile seizures that those who received the MMR and varicella vaccines separately -- probably related to the fact that infants have a higher rate of fever after the MMRV than they do after having MMR and varicella vaccines as separate injections. The American Academy of Pediatrics allows pediatricians to give either MMR or MMRV, but if they want to give MMRV as the first dose they need to inform families about the risks and let parents decide whether they want their child to receive an additional injection or have the slightly increased risk of a febrile seizure. (The second dose of MMRV, given between 4 and 6 years, is not associated with a higher risk of febrile seizures.)

Nicola Klein, M.D., codirector of the Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center in Oakland, California, advises parents to put the issue in perspective: "The overall risk for febrile seizures after any measles-containing vaccine is low -- less than one febrile seizure per 1,000 injections. It is more common for a child to have a febrile seizure caused by a simple cold than by an immunization." Still concerned? Talk to your pediatrician.

All content on this Web site, including medical opinion and any other health-related information, is for informational purposes only and should not be considered to be a specific diagnosis or treatment plan for any individual situation. Use of this site and the information contained herein does not create a doctor-patient relationship. Always seek the direct advice of your own doctor in connection with any questions or issues you may have regarding your own health or the health of others.