Get to Know the 6 Forgotten Women of the Original March on Washington

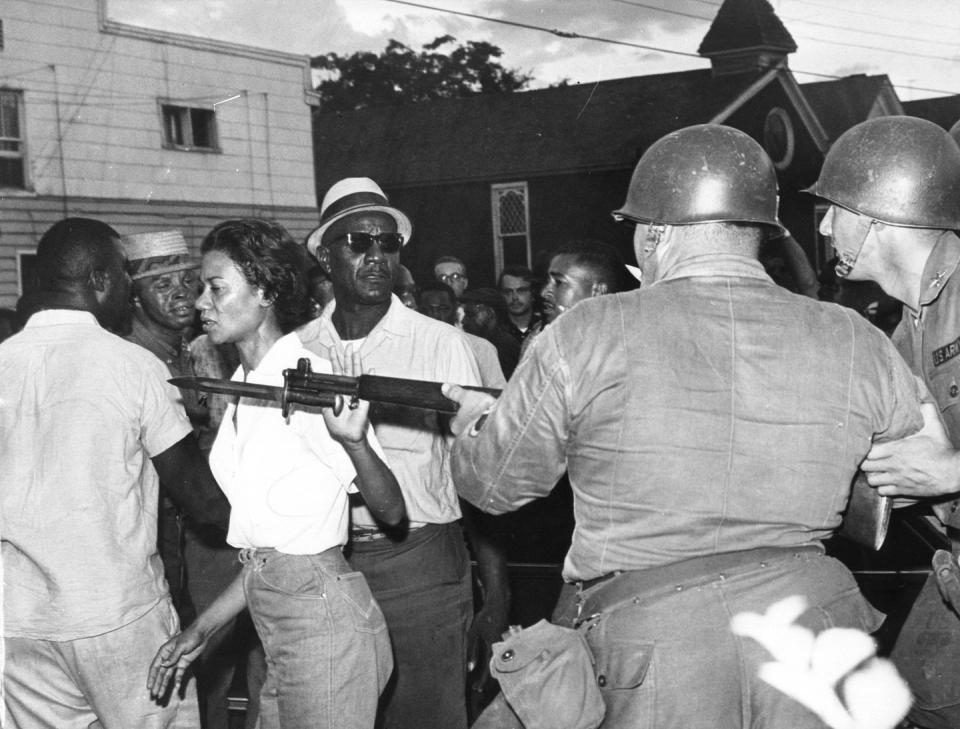

Before Rep. John Lewis' death in July, many news outlets reported that he was the last living speaker from the original March on Washington in 1963; but the last time I checked, Gloria Richardson is still alive. In their defense, she only said "hello," before a man yanked the microphone out of her hands.

The stories we’re told about the Civil Rights Movement often link power with Black men—King, Carmichael, Lewis. And the tales of the few Black women whose names we do know—Coretta, Rosa—are hardly the full story. What reaches our ears are myths of the quiet, gentle Black women who supported the men in the fight, as if they didn’t also risk their lives for equality.

In history, oftentimes violence is either seen as gendered (translation: white women) or racialized (translation: Black men). When those wires cross, there’s an electrical malfunction; a break in the circuit; the lights flicker. Black women are left navigating in the dark with only each other to grasp on to.

If it weren’t for a Black woman, Anna Arnold Hedgeman, there wouldn’t have been any women on stage on August 28, 1963. In fact, according to Professor Jennifer Scanlon, author of Until There is Justice: The Life of Anna Arnold Hedgeman, there wouldn’t have been a march at all. Hedgeman heard civil rights leaders A. Philip Randolph and Dr. Martin Luther King. Jr were both planning large marches that year and convinced them to join forces, effectively creating the March on Washington.

When Hedgeman and Dorothy Height, the head of the National Council of Negro Women, discovered that no women were listed as speakers, they urged the men to add female voices. But the men had their excuses ready: There were already too many speakers; it would be hard to pick just one; if they did choose one, a catfight would ensue. Hedgeman, the only woman on the organizing committee for the March, was forced to compromise.

The men decided they’d have a group of women stand for recognition. The “Tribute to Women” highlighted six women: Gloria Richardson, Rosa Parks, Diane Nash, Myrlie Evers, Prince Lee, and Daisy Bates.

The women being honored weren’t even allowed to march with the men. On the morning of August 28, they shuffled down Independence Avenue, while the men strolled down Constitution Avenue with the media. Daisy Bates gave the introduction of their Tribute. Her 142-word speech, written by a man, focused on women supporting the men of the movement.

After Bates' speech, Randolph stood and introduced the remaining women, even though Bates had been told that would be her responsibility. He fumbled it—he didn’t even know the names of the women on stage; someone behind him had to shout them out to him.

Of the women highlighted in this story, three are still alive. Some of their names aren’t widely familiar. Not only is the violence against Black women often invisible, but so are the very women themselves. There are many Black women fighting for our rights today who are alive and well. Are we listening to them? I’m afraid the mic might still lie beyond their reach.

GLORIA RICHARDSON (born May 6, 1922)

In 1963, a member of the U.S. Justice Department called Gloria Richardson and told her that President John F. Kennedy wanted to speak to her; she responded, “You tell those Kennedy brothers to go to hell.” The Cambridge Riots had reached a tipping point. Richardson was in a back and forth with the brothers, and she had no plans on waving the white flag.

Richardson, President of the Cambridge Nonviolent Action Committee (CNAC), started holding regular protests and sit-ins that year. The white people in Cambridge reacted with violence. The protesters responded. There were eggs cracked. Shots fired. Troops called in. The phone rang.

“The longer you go, the better you have at winning,” she recounted in 2010. The Kennedy brothers folded first. Richardson helped broker the “Treaty of Cambridge,” a civil rights and desegregation agreement, with U.S. Attorney General, Robert Kennedy.

Ahead of the March on Washington later that summer, the NAACP called to say that Richardson would be speaking for one minute and she wasn’t allowed to wear jeans. They expected her to wear a dress. She showed up in a denim skirt.

The organizers didn’t let her stay for the entire March. Before King’s speech, they threw her in a cab with singer Lena Horne and told them to go back to the hotel, saying they’d either get mobbed or start one. Richardson thinks this is because they'd been walking around with Rosa Parks, telling journalists that she was the real star of the show. “This is who started the civil rights movement, not Martin Luther King. This is the woman you need to interview.”

The men of the movement tried to force her into the boundaries of acceptable femininity–and when she stepped outside the border, they saw it as an attack. She was called a whore. Robert Kennedy asked her why she didn’t smile more. Even Dr. King tried to convince her to give up a voting boycott; she told him to go back south and mind his business.

After President Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Richardson remarried, moved to New York City, and eventually retired from public life. She still is alive and well.

ROSA PARKS (February 4, 1913 - October 24, 2005)

Rosa Parks is perhaps best known for her role in the Montgomery Bus Boycott, but her activism extended far beyond that moment. In the 1930s, Rosa Parks defended the Scottsboro Boys, a group of nine Black teenage boys who were wrongly accused of raping a white woman. She organized on behalf of Recy Taylor, a Black woman who was kidnapped and raped by six white men in 1944. She attended the Selma to Montgomery Marches in 1965, and in 1967, she investigated the Algiers Motel Incident when police officers killed three Black teenage boys. She was a member of the Black power movement, calling Malcolm X a personal hero. And still, she is known as the lady with a purse on the bus.

On December 1, 1955, while Parks was sitting in a cell for refusing to give up her seat, the Women’s Political Council (WPC), a local civil rights organization, printed flyers calling for a bus boycott starting December 5. To build their legal case, says Professor Jeanne Theoharis, author of The Rebellious Life of Mrs. Rosa Parks, women testified that bus drivers sexually and physically assaulted them. In the case that went all the way up to the Supreme Court, the four plaintiffs were all women—Aurelia Browder, Claudette Colvin, Susie McDonald, and Mary Louise Smith. On December 20 the following year, the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended. No ministers—and, in fact, no men at all—testified in front of the court. Without Black women, the boycott would have failed.

After losing their jobs and struggling to find work in Montgomery, Parks and her husband moved to Detroit, a city she referred to as the “Northern promise land that wasn’t.” The signs of segregation were gone, but their spirits were in the systems—housing discrimination, educational discrimination, and police brutality. She died on October 24, 2005. Parks continued to fight for change until the late '90s. In the Rosa Parks Collection at the Library of Congress is a paper bag on which she wrote, “The Struggle Continues.”

DAISY BATES (November 11, 1914-November 4, 1999)

Daisy Bates wasn’t a Black mother, but she spoke in their dialect when she told a white school board lawyer, Leon Catlett, to stop calling her by her first name. “You addressed me several times this morning by my first name," she said. "That is something that is reserved for my intimate friends and my husband. You will refrain from calling me Daisy.” He said that he wouldn’t call her anything then; she was fine with that.

On his deathbed, Daisy's father told her, “...hate the discrimination that eats away at the soul of every Black man and woman...and then try and do something about it, or your hate won’t spell a thing.” With her husband, she found a newspaper called The State Press, and they reported on civil rights issues throughout Arkansas. And in 1952, she was elected president of the Arkansas NAACP. In that position, she became the advisor to the Little Rock Nine.

After the Supreme Court ruled on Brown v. Board, desegregation was supposed to begin in September 1957 at Central High School. Nine Black students were chosen: Ernest Green, Elizabeth Eckford, Jefferson Thomas, Terrance Roberts, Carlotta Walls LaNier, Minnijean Brown, Gloria Ray Karlmark, Thelma Mothershed, and Melba Pattillo Beals. Governor Faubus said, “blood would run the streets of Little Rock” if Black students tried to enter Central High School, and even called in the Arkansas National Guard to support the white protesters who stopped the students from entering the building.

Bates spoke to the students' parents multiple times a day, offered up her home as a meeting place, and joined the PTA to support them even though she didn’t have a child enrolled at the school. Her business tanked, she was jailed, and she received death threats. The KKK burned a cross on her lawn, twice. Rocks were thrown through her windows.

On Monday, September 23, 1957, Eisenhower federalized the National Guard, and the same soldiers who blocked students from entering the school were now tasked with the job of protecting them. That day, the nine students walked into Central High School.

Bates went on to work for the federal government in D.C., but a stroke in 1965 brought her back to Little Rock. She died on November 4th, 1999. Bates didn’t have any biological children, but she helped rear nine.

DIANE NASH (born May 15, 1938)

In 1961, while four months pregnant, Diane Nash went to trial for teaching non-violence workshops to young Black kids. She refused to plead guilty or pay a fine, so she was sentenced to two years. She served 10 days until she was released—“I think they just decided it was likely to be more trouble than they had banked on.”

It wasn’t until 1959 when she came face to face with Jim Crow. As a student at Fisk University in Nashville, she quickly learned there were spaces where her presence was deemed illegal. “Every time I obeyed a segregation rule, I felt like I was agreeing that I was too inferior to use this facility or go to a front door,” she said.

She decided to spend the rest of her life disobeying. She became involved with the Student Central Committee, and they planned the 1960 sit-ins in Nashville that desegregated lunch counters and public spaces in the city.

In February 1961, Nash sat-in to support the "Rock Hill Nine" in Rock Hill, South Carolina because nine students were jailed after a lunch counter sit-in. She was arrested.

After an attack on Freedom Riders on May 14, 1961, she told Fred Shuttlesworth, a former student activist, that the rides must go on. He asked her if she knew that the riders were almost killed. She said, "Yes, that's exactly why the rides must not be stopped...We're coming; we just want to know if you can meet us." Robert Kennedy tried to get Nash to call off the Freedom Rides. She didn’t. Later that year, the federal government made segregated bus travel illegal.

According to an interview with Time magazine, Nash had no idea she was going to be honored at the March on Washington at all. After recruiting, organizing, and resembling people on buses to get them to D.C., she and her then-husband decided to rest. She was eating room service from a motel room in Alabama when she heard her name. “That was a weird feeling. I felt like reaching towards the television and saying I can’t get there,” she said. She regrets not being on that stage.

She didn’t get to meet him after the March, but in 1963, President Kennedy placed her on a civil rights committee; their proposed bill passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

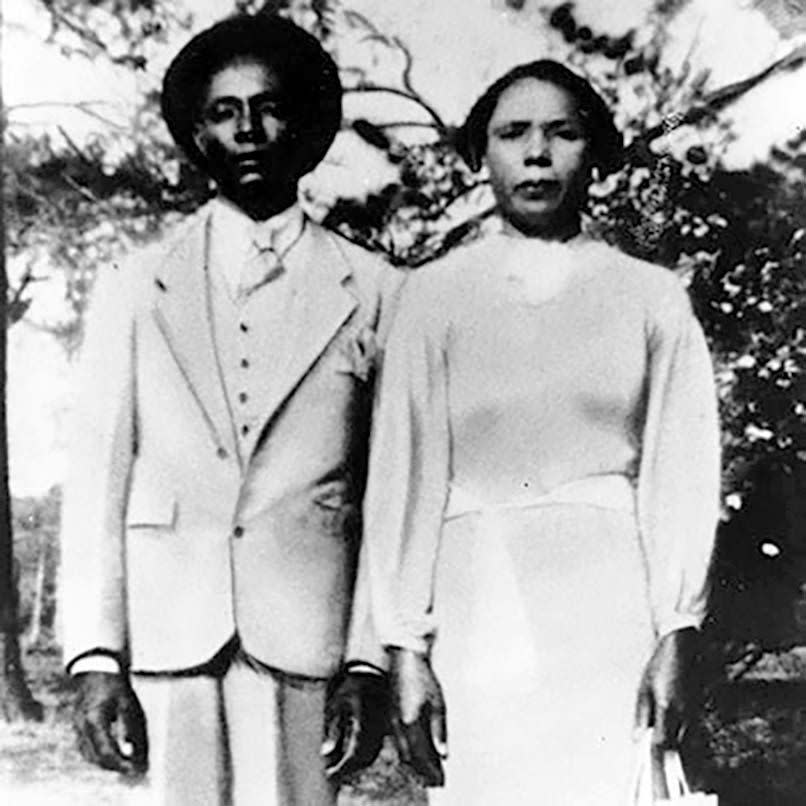

MYRLIE EVERS (born March 17, 1933)

Myrlie Evers wanted to die by suicide, but she promised her husband she would take care of the children. On June 12, 1963, outside their home, Medgar Evans was shot to death by a white supremacist, Byron De La Beckwith. She’d made the promise to him over dinner the night before.

The story of Myrlie and Medgar Evans begins like a fairy tale. The two met on her first day of college at Alcon A&M University and fell in love instantly. Myrlie dropped out of school to marry him. He was the field secretary for Mississippi’s NAACP, and together, they fought for equal rights. They organized for voting rights, equal access to public spaces, and the desegregation of the University of Mississippi. This activism placed them in the center of the crosshairs. The year before Medgar died, their home was firebombed. In an interview with her son, James Van Dyke Evers, he recalled his parents saying to him and his sister, “If you hear shots, drop to the floor and carefully crawl to the bathroom. Get in the tub. You’ll be safe there. Watch out for your brother.”

The love story ended abruptly. Myrlie opened the door and saw her husband’s dead body. He was gone. She fought for over 30 years for Beckwith to see consequences; in 1994, he was arrested and later convicted for the murder.

But Evers' life didn’t just exist at those two points, her husband’s death and his killer’s conviction. Following the death, the only reason she stayed in the public sphere was because the NAACP offered to continue to pay her Medgar’s salary if she would make appearances on their behalf. “Every weekend I was away making speeches. My eldest son began to fear that I, too, would be killed. He stopped talking and he could not hold down his food.”

Evers moved to Claremont, California and found that even though it was very white, she and her children enjoyed activities that they’d been denied in Mississippi. In the years following, Evers earned a degree in sociology from Pomona College, ran for Congress twice (unsuccessfully), became the first Black woman commissioner in LA. She later remarried, became the NAACP chairperson, and wrote an autobiography.

At the first March on Washington, Mrs. Medgar Evers was invited to sit. At President Barack Obama’s inauguration in 2013, Myrlie Evers was invited to give the invocation. She was the first woman to do so.

PRINCE LEE (1918- January 16, 2015)

There isn’t much scholarship around Prince Lee. Through the lens of history, she is seen in the possessive—Herbert Lee’s wife.

Everyone knew who killed her husband. Surrounded by a cluster of witnesses, E.H. Hurst shot him. In 1961, his body remained in the middle of the street for hours after he was killed. Bob Moses, a member of the SNCC, had been close with Lee’s husband; Lee had a car, and together they transported student activists and drove around educating Black people on their voting rights. Lee believed that this made her husband a target for violence. At the funeral, Moses recalled her saying to him, “You killed my husband! You killed my husband!”

This sort of thing plants a specific type of trauma. Every time a person dies from this kidn of violence, the roots—planted hundreds and hundreds of years ago—snake and curl their way deeper into the ground. Unfortunately, there isn’t an education on where Black mothers are supposed to place their trauma. The grief is embedded in their bodies; it’s inherited, and then it is passed down. Whether you are protesting or not, trauma still has a way of burrowing into your psyche. We may not know much about her life, but the fact that Prince Lee continued to live, isn’t that itself a protest?

We don't know for sure why Prince Lee retreated from public life after being named at the March on Washington. But she had nine children she needed to mother and shield from violence. There was no NAACP that offered to pay her bills. Trauma is haunting and cyclical; moving through our past and present, causing time to expand and contrast. When he was killed in 1963, Herbert Lee’s body lay in the street for two hours; half a century later in 2014, Michael Brown’s body lay in the middle of the street for over four hours. Both killers were never found guilty.

According to Veterans of the Mississippi Civil Rights Movement, Prince Lee passed away at the age of 97 on January 16, 2015. May she rest in peace.

You Might Also Like