What Kind of Mold Is Okay on Cheese, and What Kind...Isn’t?

We’ve all been there. You’re exploring the murky depths of your messy-ass fridge, sifting through treats and terrors in hopes of finding some suitable dinner material, when it appears: A hunk of cheese sporting a definitely-not-there-when-you-bought-it polka-dot coat of fuzzy mold. And then the bargaining begins. Moldy cheese, like all other moldy foods, should go in the garbage, you think to yourself quite reasonably. But then: Maybe that’s...okay? Like, blue cheese has mold on it, and that’s okay to eat, right? Can’t I just cut the gross-looking stuff off? Around and around we go, the menu for the evening oscillating between cheesy pasta—delicious, but maybe...deadly?—and some tired canned-bean business. This is exactly the kind of high-stakes negotiation that exactly no one has bandwidth for on a Tuesday night.

Enough! No more! There are answers to this whole is-moldy-cheese-safe business, and we must have them! We talked to Rich Morillo, a certified cheese professional (that’s a thing!) and the cheese operations manager (also a great title!) for Di Bruno Bros., Philadelphia's O.G. cheese shop—to find out what the deal is with moldy cheese and whether it belongs in the trash can or a baking dish. The answers? Kind of surprising, TBH.

The first thing you’ve got to understand is that, by and large, microorganisms like mold are what makes cheese, well, cheese. “In a lot of ways, cheese is mold,” explains Morillo. With the notable exception of fresh cheeses that are meant to be consumed shortly after they are made (mozzarella, ricotta, queso fresco, etc.), most cheeses owe their distinct deliciousness and texture to the microbiological alchemy that occurs when mold, bacteria, and other microorganisms feast on the proteins and sugars present in milk, transforming them into a wide range of flavorful compounds. (Science is cool!)

And while this whole cheese-is-mold business might be pretty obvious when you’re staring down a blue-veined hunk of stinky Stilton, you’ve also probably seen it—and eaten it—without even knowing it. You know that thick white rind on the outside of a wheel of brie? That’s mold, people! (Penicillium candidum to be more precise.) “Brie starts off looking like a disc of fresh cheese, then grows a whole lot of fuzzy white mold,” describes Morillo. “They call it ‘cat’s fur,’ and the cheesemaker literally pats all the mold down, flips the cheese over, and lets the process repeat.” The result is the savory, mushroomy white rind that makes brie and other so-called “bloomy rind” cheeses delicious but also different from all other cheeses.

trader-joes-cheese-camembert

In a lot of ways, the job of the cheesemaker and the cheesemonger is mold maintenance—making sure the right kind of mold is growing in the right place at the right time and intervening when necessary. “You’re babysitting and letting nature do its work,” Morillo says. “In the shop, one of the first things we do in the morning is check on the cheese and see if any mold has grown over the course of the night. We want the cheese to look nice for the customers, and a lot of people are squeamish around mold, so if we see a fluffy column of mold or a few specs of blue growing on the cut side of a wedge of cheese, we slice or scrape it off.”

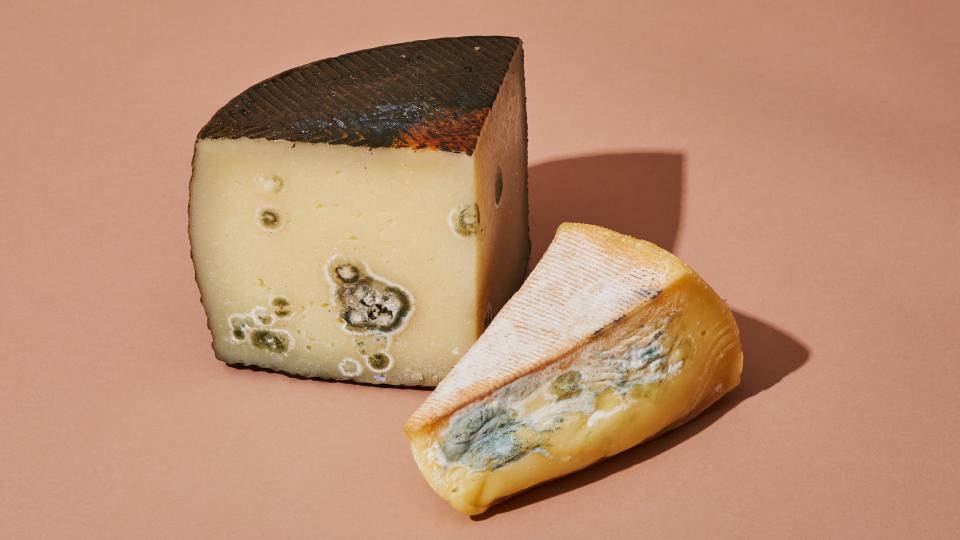

According to Morillo, it’s pretty rare that you’ll find mold growing on cheese that actually presents a health concern. With the exception of a few types that are actually quite rare to find on cheese, such as the dark black-gray mold Aspergillus niger, most mold isn’t going to hurt you at all. But that doesn’t mean that you want to eat it necessarily. Just as the molds that are a part of the cheesemaking process are integral to the flavor and texture of the finished cheese, the mold that might grow all over that chunk of cheddar you forgot about in the back of the fridge might compromise it; whether or not it tastes bad to you, the mold-affected part of that cheese isn’t going to taste the way it was meant to taste necessarily. If the cheesemaker and cheesemonger are meticulous mold babysitters, you, cheese-in-the-back-of-the-fridge-forgetter, are the irresponsible teen told to stay home with your younger sister to make sure she doesn’t get electrocuted—you’re not doing irreparable damage, but you’re probably not helping things all that much, either.

So what to do about that pesky, maybe-less-than-yummy mold growing on the cheese in your fridge? Well, most of the time you can simply cut it off and go on living your life. Mac 'n' cheese it up. Grilled cheese yourself. Whatevs. How much you have to cut off has to do with what kind of cheese you’re working with. Like mushrooms and other fungi, mold grows roots kind of like a houseplant—the fuzzy stuff you see growing on the exterior might have little tendrils that go down deep. How far those mold roots are able to penetrate depends on how dry or moist your cheese is. Microorganisms thrive in wet environments and are less active in dry ones, which means that, for the most part, mold roots will barely be able to penetrate the surface of a hard, salty cheese like Parmesan or a crumbly, long-aged cheddar but will be able to get deeper into a semisoft cheese like, say, Havarti or a mild cheddar. And as for extremely wet, fresh cheeses like mozzarella, ricotta, cream cheese, or chèvre, Morillo recommends pitching them if you see visible mold—again, not going to kill you, but the mold will most definitely have changed the flavor of the cheese, and probably not in a good way.

Okay, let’s recap. Mold is an integral part of the cheesemaking process. Almost none of it will kill you, but it could negatively impact the flavor and texture of the cheese it’s growing on or at the very least make it taste pretty different from how it was supposed to. Most of the time, if you see some mold, you can just cut it off—about an inch around and below the mold spot, if you want to be really rigorous about it—especially if you’re working with a harder cheese. Still grossed out? Throw it out. That’s what Morillo tells customers who seem especially skeptical of the whole cutting-mold-off-of-cheese thing. “If you think the mold is going to make you feel some type of way, well, it probably will.”