How 'Killers of the Flower Moon' Got Its Impeccable Costuming

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

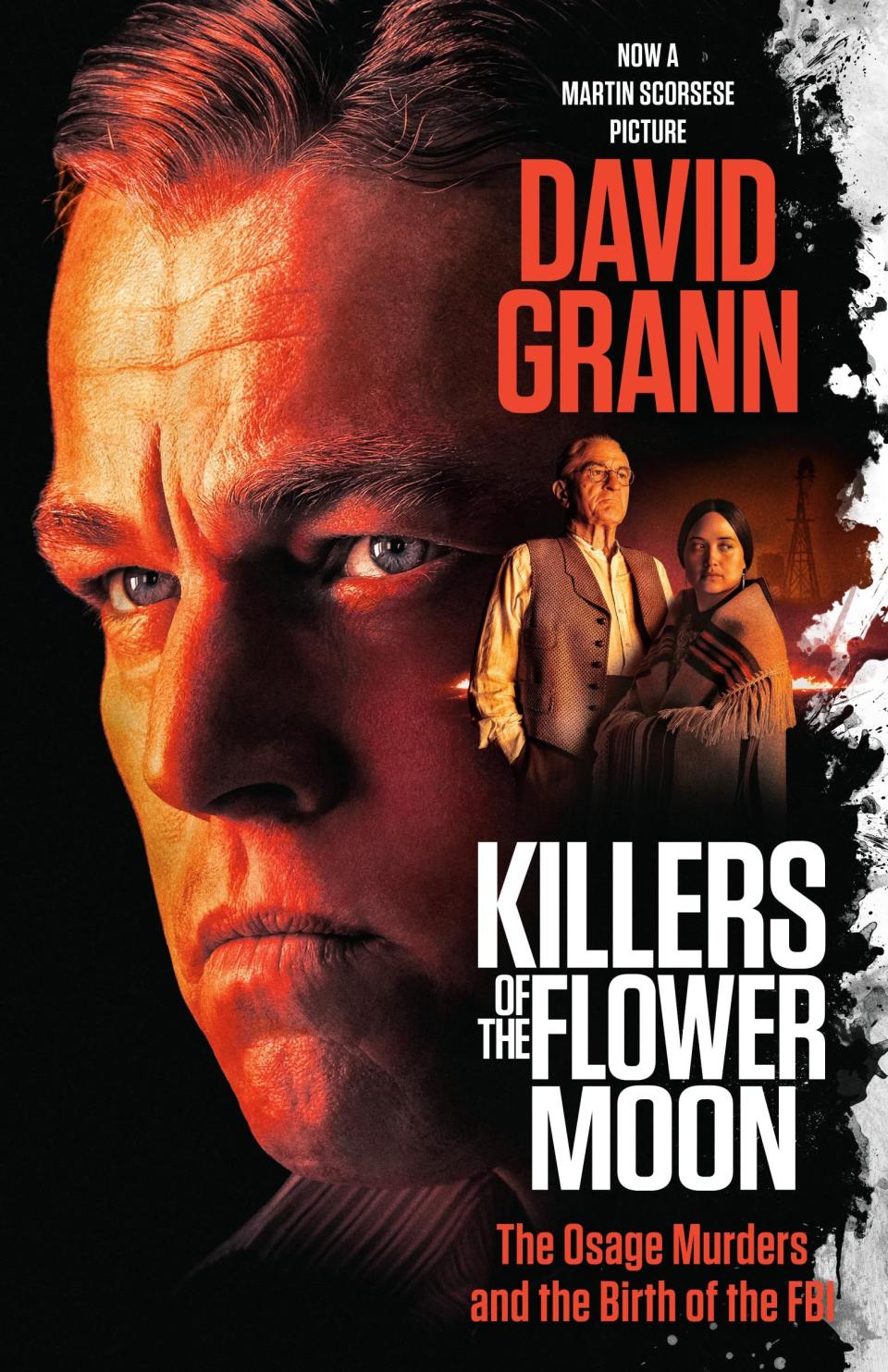

Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon, out today, is one of the year’s most anticipated movies. The three-hour, 26-minute crime epic is based on David Grann’s nonfiction book about a torrent of murders that terrorized the Native American Osage community in Oklahoma throughout the 1920s. But behind the critical plaudits, the Oscar buzz, and a starry cast that includes Leonardo DiCaprio, Robert De Niro, and standout Native American actor Lily Gladstone is a movie that chronicles a devastating period in Osage history. At the time, the Osage were per capita the richest people on the planet, thanks to their land’s oil reserves. But while this brought enormous wealth, many thought of that wealth as a curse. In time, the oil drew white men who pronounced some Osage “incompetent” and forced them into conservatorships controlled by white “guardians.” More violent elements also emerged. Soon, the Osage became the victims of a mysterious string of killings that began to look more like what it really was: systematic erasure.

Killers of the Flower Moon: The Osage Murders and the Birth of the FBI, by David Grann

amazon.com

$13.99

Knowing he had to do this story justice, Scorsese reached out to the Native American—and particularly the Osage—community and enlisted the help of tribal consultants. The result was a film that not only pays respect to the Osage’s suffering during that period, but also celebrates the beauty of Osage culture and history.

One way the movie did this was through its costuming. Scorsese brought on Jacqueline West, a costume designer famous for her extensive research. “Marty could have left it to me, but I couldn’t have left it to me,” says West, who wanted an Osage consultant to ensure the authenticity of her costuming. Osage Chief Standing Bear recommended Julie O’Keefe, whom West now calls “an angel flying into my studio.” With a background in creating museum-quality regalia that included 10 years of running a shop in her hometown of Pawhuska, Oklahoma, O’Keefe had the eye and the connections West needed.

“They’re so particular, these clothes,” says West. “Even among the people of the Osage Nation, one mother may have taught it one way, another mother may have taught it another way. But there is a classic way—and Julie knows it.”

O'Keefe came on for what West initially thought might be 10 days of consultation. “I said, ‘Mmhmm,’” recalls O’Keefe slyly before the two burst into laughter. “Our clothing is very layered. And it can be very difficult, even if you’ve been raised in the culture, to put it all on and really get it right.” Ten days soon turned into a tight-knit partnership that lasted through the production.

West and O’Keefe reunited to speak with Harper’s Bazaar about the process of creating the movie’s detailed costumes, the rich traditions behind the clothes we see onscreen, and the resounding support they got from the Osage community—which uncovered more than one piece of physical history.

The accuracy and craftsmanship of the costumes in the movie is outstanding. It’s clear there was a lot of significance placed on getting it right. Tell me a little about the role of traditional clothing in Osage culture.

Julie O’Keefe: We have a traditional dance called the In-Lon-Shka. We meet every year in June for three four-day weekends. There are three Osage districts that attend, and some of the nuances in our clothing depend on which district we come from. So for Gray Horse, you may see fringe on the outside. But for Pawhuska, which is my district, you flip the fringe on the inside. A lot of our families do that. Then I’ve seen different uses of ribbon. Some clasp them with vintage-looking brooches, but if you go to the Zon-Zo-Li district, they tie their ribbon in a bow in the back. They don’t use a brooch at all. So when I’m at the dances, I can tell who’s from which of the different districts or different families based on how they’re doing those things. And even though we’re each expressing ourselves in those details, our look and our dance has not changed for over 150 years. We make sure that when we’re within that tradition—in that culture, in that place—we are honoring and carrying it out. And one of the ways we carry that out is through our clothing.

Did you have a lot of archival imagery available to reference?

JO: Jackie had it all when I got there. She had thousands of pictures on the wall by the time I walked in, and it was fabulous.

Jacqueline West: I started doing research after I was first hired by Mr. Scorsese. It was during Covid, when we were all still pretty locked down. So I worked about four months in Deadwood, South Dakota, just doing research online and in libraries in the area. My husband is a writer and a journalist, and he’s also part Native American, so he got involved, and we just sat and pulled research from everywhere we could.

We live right by the Sioux reserve, where there are incredible Native American libraries. So I did my own research before I even got to Oklahoma, where we shot the film. Once I arrived, because of the generosity of the Osage people, everybody started bringing me the most incredible family photos—one of which we re-created in the film. So it started with research I came with, but it then got really brilliant after I got to Oklahoma.

And I don’t know if you know this, but the Osage were some of the only people, aside from maybe the British royal family, who could afford to make home movies in this period. So there are brilliant archived family movies of them flying their own private planes; riding around Pawhuska in these beautiful cars, Duesenbergs and Pierce-Arrows; shopping in Paris and vacationing in Colorado Springs. So all that was another unique resource. But it was all driven by Marty and his passion to get this absolutely right in deference to the Osage Nation. We all took our research beyond and beyond. We put every research photo up on the wall, and we’d check them off whenever we got one into the film. And by the end of filming, almost every photo had a check on it.

In the 1920s, Osage women wore the finest jewelry and furs and fashions from all over the world. You show some women in the movie dressed that way, with extra flapper flair. Did you have to exaggerate those looks to really telegraph that almost unimaginable level of wealth?

JW: A lot of it came from those home movies. They went to Paris and New York City; they shopped at Tiffany’s. They had very good taste, and there was no finery that they couldn’t afford. We didn't have to create any exaggeration for effect.

JO: Can I add one thing to that? There was a mercantile there in Fairfax called the Big Hill. And Tiffany’s actually had a small counter there, in little Fairfax, Oklahoma. And there were something close to 15 dealerships of the finest cars. All in this place where you could also buy furniture and caskets! I’ve been through that building—we were actually trying to restore it and I was helping Chief do some work on it—and it was humongous. It was of the finest quality with small boutiques, and while they didn’t really have department stores per se back then, it was really the first of that kind of thing for that area, and for Oklahoma.

JW: I’d say it was like Harrods of London—but in Fairfax. And it was extraordinary. Every picture that I pulled, every screenshot I pulled off of a home movie, there was an elegance to it. The Osage were quite elegant, and they wore it all very well. I wanted to portray that elegance in this film.

The real Mollie Burkhart (played by Lily Gladstone in the film) is said to have stood out somewhat in the streets of Fairfax because she tended more toward wearing traditional Osage clothing than others in town. The book points out her fondness for wrapping herself in Osage blankets. How did you use her fashion to set her apart from other characters?

JW: She’s the moral compass in this story. She wants to maintain tradition and hang on to her heritage. And she’s also, as you see in the film, quite desirous of her mother’s approval, her mother’s love. Her mother, Lizzie Q, was very traditional too, and I think that made Mollie the most traditional of the sisters. Anna was the most modern, and the other sisters were each some degree in between. But for me, Mollie in the film stands for the real Osage woman. She’s a symbol of the Osage Nation.

JO: From my perspective, the scope that I looked through was the history of the struggle: what this family had been through, what the entire [Osage Nation] had been through. We were known as the “Children of the Middle Waters.” We came from Missouri to Oklahoma. We chose that land because we knew the buffalo went through there. We picked up our housing and took our horses and took our children, and we traveled. We went buffalo hunting. We would clean our own skins. If it was a good hunt, we would cure the meat and we would have meat for the year. There was this whole traditional life that never involved money. So you have people like Lizzie Q, a traditional mother, someone who was raised on the plains.

And then the children are taken away to be sent to missionary schools or military schools. That’s forced on us. Then you have those children growing up and coming back into their community, like Mollie or [her] sisters, who were of the first generation to have to do that. And they’re coming back as English-speaking children to Native American parents, into a situation where they’re immigrants in their own land. They’re asking themselves, How do we how do we fit into this? Our skin color is different. Our ways are different. Who are we?

So I look at Lizzie and Mollie and her sisters as a family unit: You’ve got Lizzie still trying to grapple with the fact of this new life, which she’s not going to fit into. She’s set in her ways. You’ve got Anna, who completely goes off into this contemporary world. So her clothing is a modern flapper aesthetic. Then you’ve got Mollie, who is expressing herself through her clothing and saying, I am still here. I am grounded in my culture. I still know who I am. So she’s wearing these traditional clothes that, at that time, had not changed for 75 years. As I told you, for us it’s been 150 years; for her it had been over 75 years that the traditional clothes and silhouettes had been the same.

Many women, like Mollie’s sisters, married into [white] culture. The culture was being forced upon them, so how do they stay safe? They marry into it. So they start dressing in more contemporary clothing. But there’s a piece of them that still wants to expresses their own culture. So you see them wearing these blankets as shawls over their contemporary clothing. And we still do that today. So we’re telling that very human story through those sisters’ clothing. You can see their struggle to be accepted into this new world by how they’re expressing it through their fashion.

Given that there are some portraits of Mollie and her sisters available, did you approach their costumes by primarily re-creating their looks, or did you use them more so as a starting point?

JW: The way I’ve always approached a movie is to get to know the characters really, really well, and then you take them shopping in that period. You only select for them what you feel they would have selected for themselves from what would have been available to them given their economic circumstances. If you approach it like that, from the inside out, then the characters almost pick their own clothes. So I tried to do that with the sisters. With Mollie, sometimes we used portraits of her from that time. We tried to create some of those outfits exactly, but we only had a certain number of photos draw from. They didn’t have iPhones back then; they weren’t snapping 20 photos of each other a day. And the reality is that people had far fewer clothes in that period. Go to an old house from the 1920s and you’ll see that the closets are so tiny. We weren’t consumers in the same way we are now. So on every film I work on, I build a closet for every actor. Then when they go to get dressed in their trailers or dressing rooms, that’s their wardrobe. Those are the clothes their character picked, that they own. Then I kind of just let the actors pick once they’re the character and no longer an actor. They’re very good at that.

How much of the costuming was created specifically for the movie? And how did Osage artisans contribute?

JW: Except for the large crowd scenes and the street scenes in town, almost all of the costumes were specially made. All the Osage clothing we made from scratch. Even Osage men had a particular look. They weren’t going to wear suits like the [white citizens]. They took on more of a western look, but made it Osage. There was a certain Spanish-heeled boot that I had made, and a certain pant that was like a buckle back moleskin, almost a military pant, that had a western twist to it. I pulled a lot of photos and then just started making huge numbers of them in Budapest and Los Angeles. For the ensemble cast, I found sewing rooms, but for all the principal characters we made everything in-house. The exception was for jewelry and accessories, which were made by incredible Osage artisans who Julie brought to us.

JO: There’s a few things in the movie that you’re going to see a lot of on people. You’ll see armbands and ball-and-cone earrings on both men and women. The tradition of making these came from “peace medals” or “treaty medals” [given to tribal leaders by the U.S. government]. When those treaties would be broken, we’d strike those medals, melt them down, and make our own silver. So you see these silver armbands on some of the gentlemen onscreen.

We had a silversmith in Oklahoma named William “Kugee” Supernaw, who has a store called Supernaw’s. He is a master metalsmith, and his son is, too. They made a lot of the Czech seed beads that you see around the Osage women’s necks, which are a staple for us.

And you’ll see a lot of ribbon-work blankets. We had many artisans who had family patterns to work off of. Janet Emde was one, Ruth Shaw was another. Anita Fields, an Osage artist who’s well known around the world, wanted to contribute and made a blanket for the movie. Marie Lookout, who comes from a family of some of the finest ribbon-work makers, made two blankets for us.

We have a parade scene where we see several beaded blankets, made by Molly Murphy Adams, who isn’t Osage but is Oglala Sioux. She beaded flags all over the front of these two-yard-by-two-yard bolts of cloth. She went to our Osage tribal museum, which is one of the oldest tribal museums in United States, for research. There we have some blankets from the 1920s. War mothers at that time would have dances where they’d pray for all of their husbands and sons going to war. And they would decorate their blankets with, say, airplanes if their men were in the Air Force. There’s a spectacular blanket from the 1920s with these old airplanes on it by a Charles Lookout.

So we had these types of resources. We found some families that had all these things in their trunks even older than 1920. We were really able to capture a lot of history in the movie thanks to these particular families who have carried these traditions down.

Hollywood’s depictions of different cultures often end up using anachronisms, sometimes in error and sometimes for seemingly practical reasons. Dances With Wolves was a celebrated film, but it nevertheless earned some snickers from native Lakota speakers who know that it’s a language that uses gendered speech and noticed that all the characters, including the men, spoke using the feminine grammar. How important was it for you to make sure the visual language of this movie was spot-on, even if those details go unnoticed by most moviegoers?

JW: For me, it was the most important note I felt I had to hit. So when Chief Standing Bear told me how perfect the costumes were, that meant more to me than anything any critic could say. Because he represents his people. He lives among them, works among them, fights for them. His approval meant everything.

But working with Julie, I always had a feeler out there. She would bring people from the Osage Nation to see what we were doing and give their approval. I haven’t always worked that way before. Usually the only person I show my work to is the director. But Marty wasn’t like that. He trusted me, he trusted that I had a consultant from the Osage, and he trusted that I wanted to have somebody to say, This is right, this isn’t. Because these are old traditions that need to be respected. You don’t want to make a mistake. We had two wonderful people who stood on set with the background actors: [set costumer] Alaina Maker and [Osage actor] Joel Tallchief Lemon. She watched all the women and he watched all the men to make sure their costumes were perfect. Nobody got away from them, and if anybody did, they would run right after them and check their costumes.

JO: It was a community project in a way. Because the community wanted it right, those families wanted it right. A horrible time in our existence is being told on the screen. That’s hard enough. So what we really wanted is exactly the type of thing that Martin Scorsese is known for: authenticity with a big A. He and Leo came to dinners with our elders. They had discussions with our community. After that, everyone in all three of our districts had their ears out—if we needed something, if we needed photographs, if we were stumped on something, if we needed feedback, they came to help.

I had a question one day about an Osage woman riding on horseback. So I called my aunt Kathryn Red Corn, who’s in her 80s and actually helped [Killers of the Flower Moon author] David Grann do research for his book. I asked her, “What would this Osage woman be wearing?” And she said to me, “Julie, first of all, there’s going to be no saddle. If you had to get on your horse and go somewhere, it didn’t matter what you had on, you got on your horse.” So I go back to our production and I say, “Go ahead, put that skirt on her, no saddle, and she’s gonna ride the horse.” And the extra did! That was the kind of resource we had in the community. I’m a big believer that if you’re asked a question, you do not answer until you know you have the right answer. When I took information back to Jackie, I knew it had come from the best resources within the community. They all wanted to help because they all really wanted to get it right.

Julie—were there any outfits or garments or accessories that were particularly meaningful for you to work on and see onscreen?

JO: Oh my. There’s so many. I would say, the wedding coats are some of the most spectacular costumes in the film. The history of those coats started all the way back in Thomas Jefferson’s time, when we would send delegations to meet with government leaders, the way diplomats would do today, and we would exchange and give gifts. And there’s a story about a chief admiring, I think, President Thomas Jefferson’s coat, and Jefferson takes it off and gives it to the chief. But the thing about Osage men is that they’re huge, statuesque men, very great in stature. So the coat didn’t fit. Instead, what the Osage did [when they received these coats] was to give the coats to their daughters. It brings status to a daughter who wears one. Then when she brings it home, the Osage start putting their own ribbon work and twist on the coat. And when she wears it on her wedding day, everyone knows that she comes from a very prominent family.

My second answer would be the blankets. Blankets, shawls, broadcloth, and ribbon are extremely important to my tribe—for both men and women. And there’s meaning to how the men wear them, same as I described earlier for the sisters. Look at the character of Chief Bonnicastle and how he’s wearing the blanket over his suit. This tells you he is an educated man. He’s gone out to the white man's schools and come back. So he wears the blanket in a very important way that lets you know he’s a leader. Then there are the ways a roadman—or a holy man—wears the blanket around his waist. When Ernest is getting married to Mollie, he’s wearing a blanket like that and so is the gentleman who’s officiating the wedding. So there are nuances to those blankets and how they’re worn that tell you something about the events happening at that time.

JW: And Pendleton was a great collaborator. I’d send them, say, a portrait of Mollie wearing a blanket, and they’d re-create it for me in the exact right colors.

How many families could claim their daughter was wed in one of those wedding suits? And does that tradition live on to this day?

JO: As those were passed down, we kept them in trunks. I’ve seen very old ones with a lot of families. But over history, those delegations stop going out, treaties are being broken, everything’s changing in the political landscape. And when those delegations start slowing down, women can of course no longer receive those coats. So the Osage start making their own. And after a wedding, a bride would take all of it off and give it away to someone who had helped them, or to a bridesmaid, or to someone else for different reasons. But in 1951 or 1952, we had the last arranged Osage marriage. Before that, everything was arranged. And so that tradition [of passing on the wedding suit] stopped. But we didn’t want to let go of that tradition.

So what we do now is this: We have something called the “passing of the drum” that happens every four years at our dances. It happens in all three of our districts. We have this big celebration, huge dinners, joyful dances. And when that drum passes, all of these bridesmaids will come out—the last time we did this was last year, and it had nine bridesmaids—and all these different families will have made brand-new wedding coats that they give away. Everyone waits to see them. I have an auntie that sits next to me; she loves to sit and look at all the wedding coats. She even has opera glasses—and we’re really not sitting that far away! So that’s one way we have taken a tradition and then incorporated it into our contemporary lives.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

You Might Also Like