"To Kill a Mockingbird" Broadway Cast Discusses the Story's Complicated Legacy

It’s fall, a.k.a. back-to-school season, which means that all around the United States, students are either receiving battered copies of Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird for the semester or being quizzed on the classic novel for summer reading. The book is a staple of middle and high school English curriculums around the country — it’s used as a way to discuss racism, inequality, and history in a way that educators think is accessible for young people. But as the way we talk about race evolves, as language around inequality changes, and as opportunities hopefully increase for marginalized people to tell their own stories, it’s worth examining why To Kill a Mockingbird is one of the most widely used examples of literature on race, especially when this story is continually retold in different forms.

Because To Kill a Mockingbird’s legacy is still ongoing. Since the book was published in 1960, it has been adapted into a 1962 Academy Award-winning film and multiple stage plays; it also exists in a different form but with some of the same characters in Lee’s own Go Set a Watchman, released in 2015 before her death the following year. Most recently, screenwriter Aaron Sorkin adapted the novel into an extremely successful Broadway play, where adult actors play the novel’s central children: after beginning its run in 2018, it’s currently the highest-grossing American play in Broadway history.

For those who have been lax about summer reading, the events of To Kill a Mockingbird take place in 1930s small-town Alabama. The protagonist is the plucky, endlessly curious Scout Finch, who explains what happened in the town of Maycomb after her father Atticus Finch became the defense attorney for Tom Robinson, a black man who has been wrongfully accused of raping Mayella Ewell, a young white woman.

Over time, and especially with the influence of actor Gregory Peck’s Atticus Finch in the To Kill a Mockingbird film, the material has become an American cultural reference point. Oprah Winfrey once hailed it “our national novel.” The New Yorker called it “a kind of secular scripture, one of only a handful of texts most Americans have in common.” It’s more than a book: it’s held up almost as a system of thought. And it’s one that provokes questioning in the way it perpetuates Atticus as a white savior, in the way it presents black people — and in the way people (especially white people) uplift it as the ultimate writing on race and justice.

Broadway’s To Kill a Mockingbird has crucial changes.

The Broadway version, to its credit, fills some of those gaps in how the story’s black characters are presented, which is a huge reason cast members like LaTanya Richardson Jackson agreed to be part of the production in the first place. Jackson plays Calpurnia, the Finch family’s maid and maternal figure, a role that has been expanded to have more discussions with Atticus; during several of those conversations, she checks him on his white privilege. In the play, when Atticus says the children shouldn’t have to be afraid to walk around where they live, Cal wryly remarks, “Well, let me see if I can find a way to relate to that.”

“What Aaron Sorkin did was looked into this time, into 2019, by giving Calpurnia agency, and giving Tom some degree of agency, so that we were not fitting as props or as scenery or as devices used to move the story,” Jackson tells Teen Vogue. “Part of the issue that the culture has in understanding African Americans is that no one ever asks, really, what the African American is thinking, as if we exist in some sort of void. It's important now that you hear some, you don't hear enough, but you at least hear something of what this woman is thinking as it relates to her and her people.”

For many white teens in the United States, To Kill a Mockingbird is an early entry point into talking about racism, but for children of any race, it might be taught in class as an intro to southern gothic literature and literature in general. Its reputation as a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel precedes it. Gideon Glick, who plays Scout’s eager childhood friend Dill (who is white) on Broadway, remembers reading the book in seventh grade, and how it taught him how to be a “good reader” and to look for theme and metaphor. Part of the reason the book has become so beloved is because the prose is clear and easy to read. Also, as Vox’s video series “Overrated” points out, To Kill a Mockingbird was published in a time where cheap paperback books were gaining nationwide popularity and published en masse, which meant they were often used in schools because of their low price. The book benefited from exposure along with the clarity of its writing on topics that are really complex.

“I didn't realize how different I would feel performing this story, this black man's story, in front of all these white people who are, you know, yeah, I imagine a lot of them [are] liberal-minded but still benefactors of this system,” Akinnagbe tells Teen Vogue.

It’s also conveniently written from the perspective of a white person, which is likely a significant part of why it was published in the first place, and why it’s reached such acclaim. But that white perspective limits the novel’s scope, even as it widens the audience for a book about race. “I think the fact that To Kill a Mockingbird was written by a white person made it much more palatable for [white] people to talk about race, because it was from the white gaze, from the white lens,” Gideon Glick says. “[That’s] probably why it has been consumed as it has, beyond that it's really profound writing.” He adds, “I do think we're in a time where we really are trying to make space, and that makes me optimistic. I think we have so much work to do.” Other popular plays on Broadway have and will interact with blackness, from the classic novel adaptation of The Color Purple to the provocative 2019 Broadway addition Slave Play.

And To Kill a Mockingbird’s story was profound for its time, and even now, it can still have profound effects in the questions it raises, and in the productive discussions about what it lacks. “It's well-written. It addresses what's fundamental about this country, but it does it through the eyes of this precocious child,” says Gbenga Akinnagbe, who currently plays Tom Robinson on Broadway. “We all sort of see ourselves in Scout Finch. We all, like her, are able to see and discover horrible things, but through the eyes of a child who has very little fear … I feel fortunate to be able to do a play that can can create room for this conversation.”

LaTanya Richardson Jackson and Jeff Daniels

Photo: Julieta Cervantes

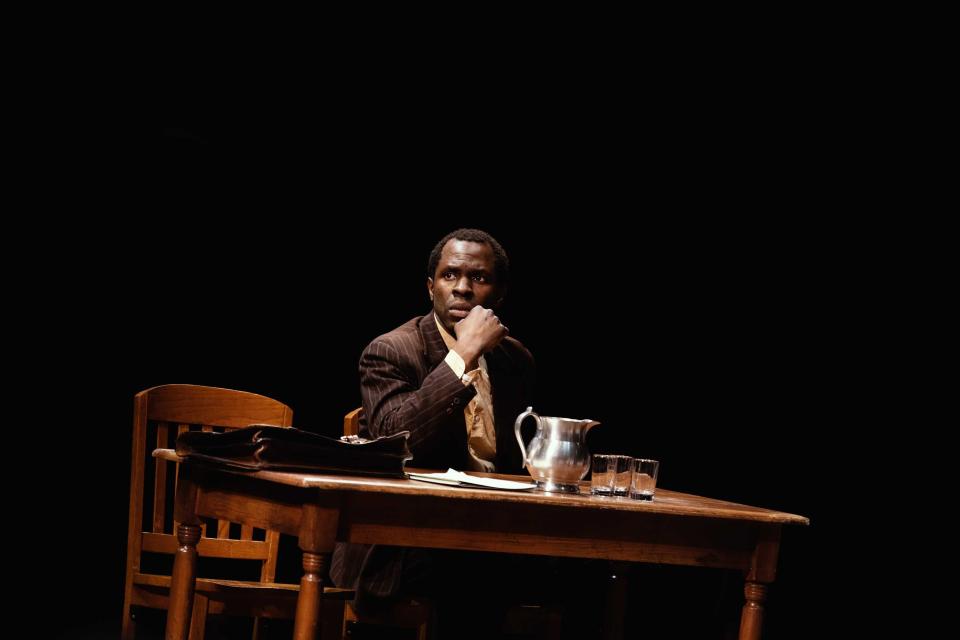

Gbenga Akinnagbe

Photo: Julieta CervantesDiscourse around the classic novel is ever-evolving.

Each iteration of the story, and each new generation of readers, brings new and varied waves of controversy. The book has been banned on and off in different school districts basically since it was published — originally, because of its rape storyline, but more recently, because of its use of the n-word, which concerned parents have called out as offensive (which is, of course, the very point of its original use in the book). The Aaron Sorkin play has had its own share of tumult, including a lawsuit from Lee’s estate about character changes made in Sorkin’s adaptation; ironically, those changes (which include giving greater voice and autonomy to the book’s black characters like Tom and Calpurnia) partially address an ongoing shift in how academics, writers, and teachers think about the book and what they view are its shortcomings.

In July, author Shannon Hale tweeted, “My son was given a reading assignment for 10th grade: TO KILL A MOCKINGBIRD. He was already assigned this book in middle school. The older sister of his friend has been assigned it 4x in 4 different classes. Other books exist. That deal with racism. Written by POC even.”

The tweet touched on an argument that’s been forming in some circles for a long time: Too much rests on To Kill a Mockingbird to do all the heavy lifting in educating young people about race. It cannot possibly hold up to the pressure — especially because its author, ultimately, is a white person. The New York Times reporter Kendra Pierre-Louis argued in September that the book also “contains problematic, ahistorical stereotypes about race and racism,“ adding, "I'm not saying the book should be banned. But that it's taught as an accurate rendering of historical fiction when really at best it’s wishful thinking it's [sic] a problem.” Pierre-Louis offered up an alternate book, Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry, another popular children’s/middle grade novel that tackles themes of racism and systemic inequality during Jim Crow, but is actually about black children (and is written by black writer Mildred D. Taylor).

And back in 2015, professor Osamudia R. James wrote in The New York Times about how the “myth” of Atticus can be harmful if all white people take from it is that we should try to “love everybody.”

James writes, “...[Atticus] keeps good white liberals from reconsidering the fact that they live in white neighborhoods; from challenging administrators about the racial segregation of their children’s schools or white supremacy advanced in the curriculum; or from acknowledging how they benefit from a system that keeps people of color laboring in their homes but excluded from their social and professional spaces.”

So, what do we do with this narrative?

To sit and watch To Kill a Mockingbird on Broadway in 2019 brings up questions of who gets to tell their story, who is that story for, and who gets to see it. Broadway has its own problems with race and class divisions. Tickets are expensive, and theatregoers, while getting younger, are still overwhelming older and white. When I saw the play, one of the only people of color I saw in the orchestra was Lin-Manuel Miranda, who happened to be attending that same night.

There’s a serious content and audience gap in that; how Broadway’s To Kill a Mockingbird can push me to question the idolization of Atticus and my own leftover notions of white heroes from my teenage reading of the novel, but also how it can leave me and other white viewers with the feeling we’ve done something anti-racist just by seeing the production and having those thoughts (we haven’t). It’s the irony in how I can see the systems at work that got me into this play audience in the first place, but how I also get to leave the theatre and continue to benefit from my whiteness. It shouldn’t be mutually exclusive to have accurate representations of marginalized voices and then be able to show that product to black and brown audiences who need that representation. On the other hand, white people, of course, need to experience and engage with stories about non-white people in order to meaningfully counteract the white supremacist systems they benefit from.

As a black man in America acting out racial violence nightly, Akinnagbe has engaged with this tension directly. In May, he wrote an op-ed for The Washington Post titled “Every night, racists kill me. Then I leave the theater for a world of danger.” In it, he discussed how his feelings about portraying Tom changed over the course of going from rehearsal to actual stage performances in front of majority white audiences.

“I didn't realize how different I would feel performing this story, this black man's story, in front of all these white people who are, you know, yeah, I imagine a lot of them [are] liberal-minded but still benefactors of this system,” Akinnagbe tells Teen Vogue. “Then I would go outside and it [would] still be America and me in America.”

The To Kill a Mockingbird play cast has ideas for a new slate of required reading: Akinnagbe suggests Race Matters by Dr. Cornel West, one of the first books to “define the vocabulary for what has really been my American experience.” Glick recommends the Pulitzer Prize-winning drama Fairview from writer Jackie Sibblies Drury, as well as Ta-Nehisi Coates’s Between the World and Me, a book that “opened up” his understanding of hatred and xenophobia and “challenged the white gaze.” Jackson loves Ijeoma Oluo’s book, So You Want to Talk About Race, as well as Oluo’s Medium article, “The Anger of the White Male Lie.” Other favorites include Beverly Daniel Tatum’s Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria and Their Eyes Were Watching God by Zora Neale Hurston.

“I hope [young people] are reading,” Jackson says. “Books are still a great way of being with yourself and helping to code some sort of idea about your life and who you want to be in the world.”

And as with all stories, on the page or the screen or the stage, To Kill a Mockingbird's effects come when people act on what they learn, and when they challenge their own ways of thinking as a result.

“I think the play we do is one of the most important plays on Broadway right now … if we take the opportunity, if we take it a step further after the play to have some uncomfortable conversations,” Akinnagbe says. “But on the other hand if we don't do that, it can allow white people to feel good about being white and liberal and not do anything.”

Jeff Daniels

Photo: Julieta CervantesLet us slide into your DMs. Sign up for the Teen Vogue daily email.

Want more from Teen Vogue? Check this out: Netflix's When They See Us Is a Lesson on the Danger of Implicit Bias

Originally Appeared on Teen Vogue