Ken Burns’s Baseball Documentary Is the Unlikely Style Inspiration We Need Right Now

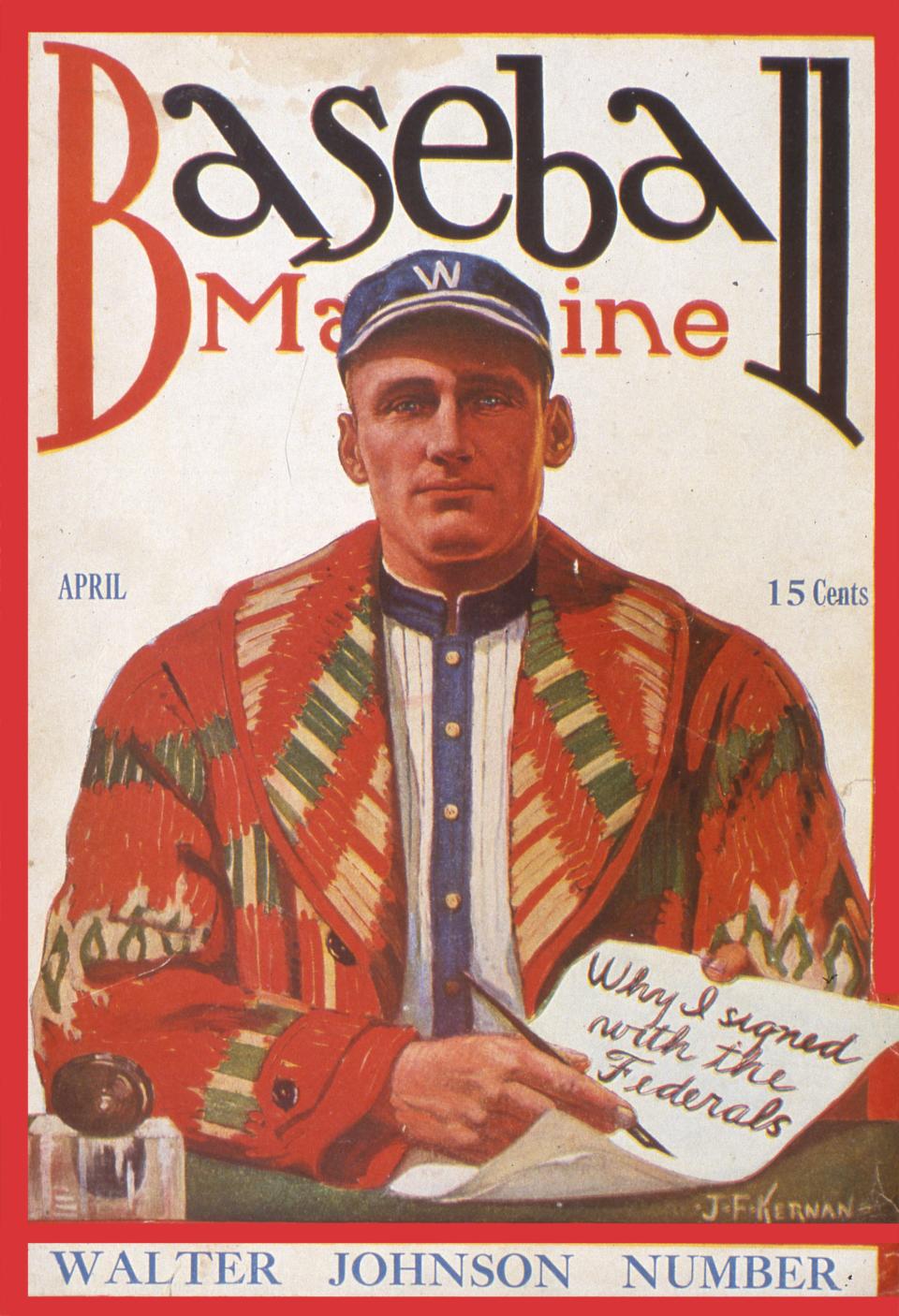

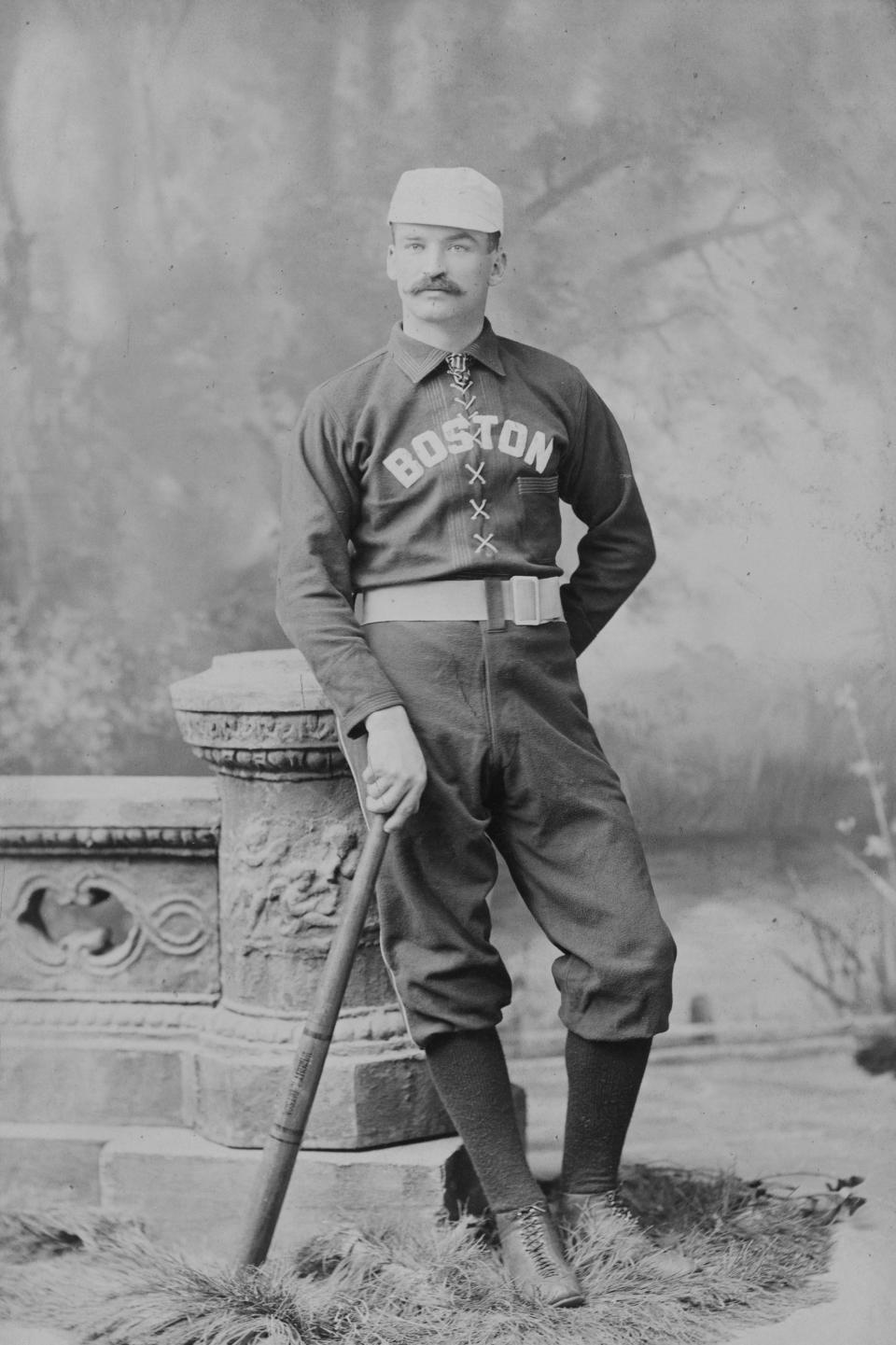

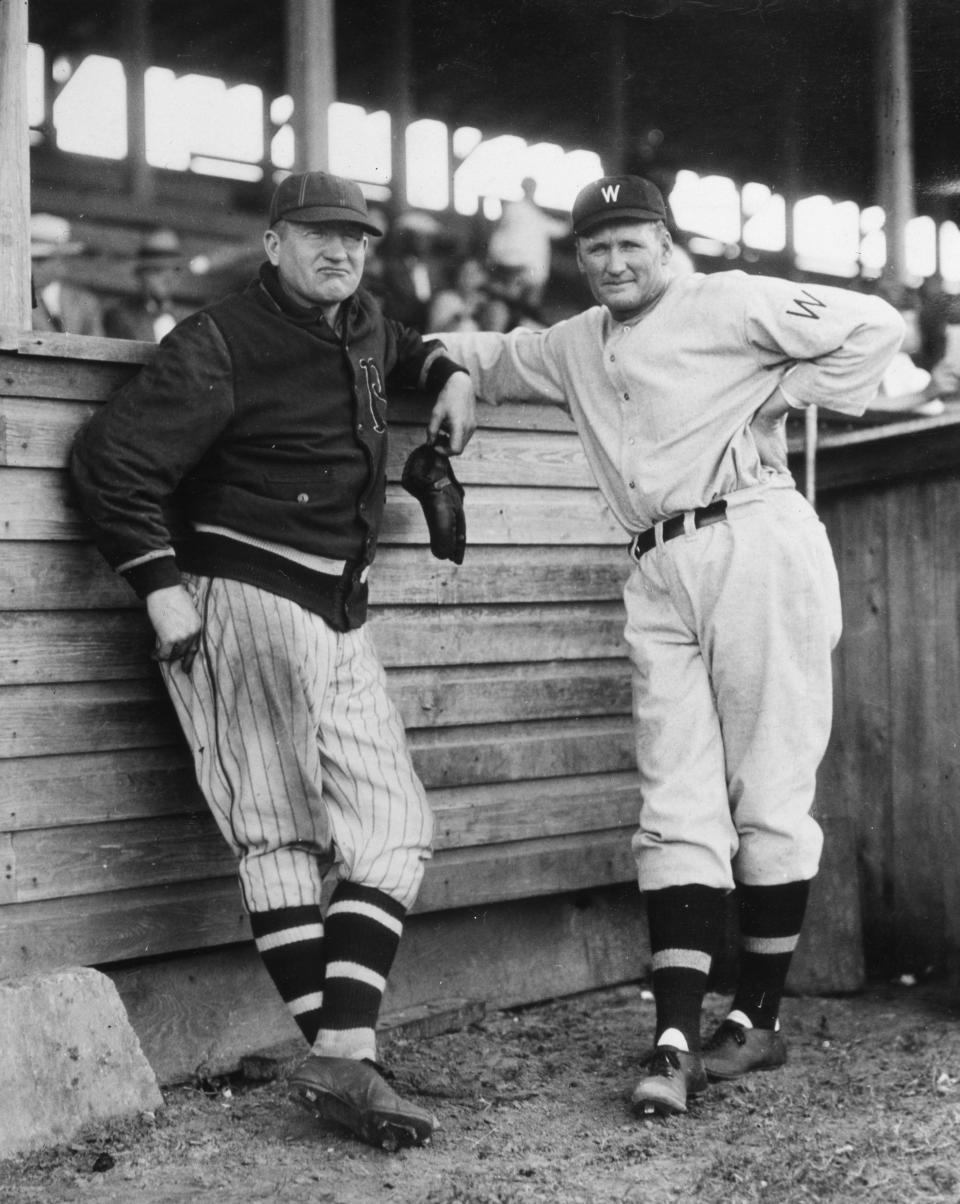

There’s a moment early on in Ken Burns’s Baseball, his mammoth 1994 documentary about the sport, where the camera pans and zooms onto an old issue of Baseball Magazine from 1915. Burns’s trademark effect glides across, then settles on, pitcher Walter Johnson, writing a letter while wearing a Navajo blanket jacket over his uniform. The coat—bright, shawled, fitting like a bathrobe—is a shock of colors, red, orange, and green, and jumps off the screen. It’s a museum piece, tough to find a century later, and rare enough that even its re-executions, from Ralph Lauren’s Country line or Pendleton or Bob Mackie, run into the three figures. A few minutes before in the film, some would-be Johnson opponents stand at attention, uniformed in similarly cut team-issued sweaters, belted and adorned with sewn-on logos and shawl collars. Their manager wears a slouchy three-piece suit and a shirt with a detachable collar. A bit later, Burns’s camera pans to a crowd watching a downtown scoreboard, and everyone there wears suits too. PBS made the documentary free to stream last week, in the wake of Opening Day being postponed. When I turned it on, I was expecting mostly a reprieve from the pandemic. Instead, I found myself elbows deep in a fashion encyclopedia.

Walter Johnson Baseball Mag

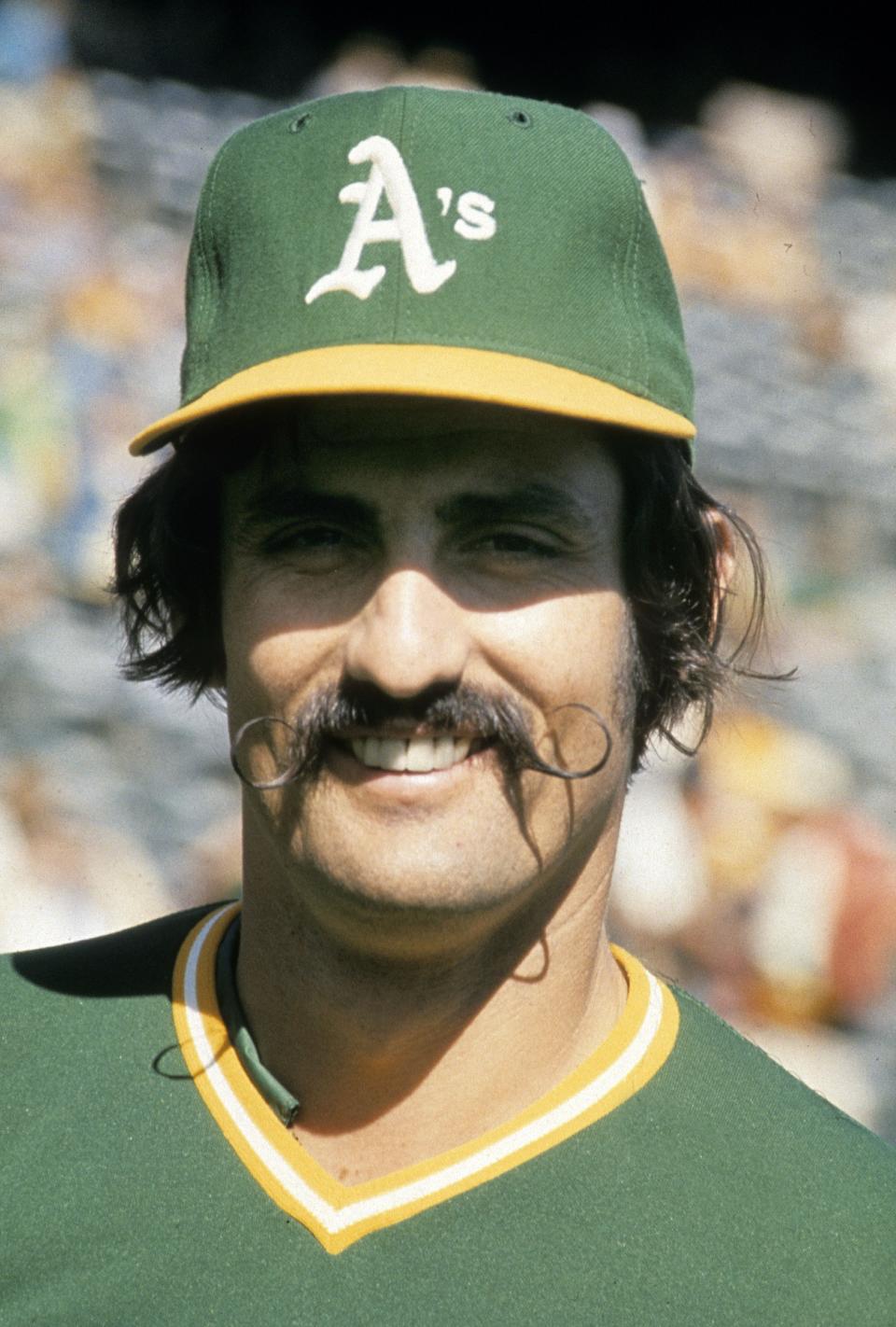

It’s a bit of a shock. Uniforms are chic things, of course, and looking back is always good for inspiration, but who would think an April Sox-Yankees–length baseball documentary could function as a style archive? Made up of nine episodes (or innings), running 18 and a half hours, Burns’s film begins with baseball’s invention in the mid-18th century and follows it through to the Blue Jays’ first World Series title, in 1992. (A tenth inning, produced in 2010, is available on Amazon’s Prime video service.) Spending a couple hours per decade, Burns unfurls a century’s worth of the sport, and in the process coolly covers a lot of sartorial ground. The film is a virtual repository for eons of American clothing, tracing, with photos and footage, a timeline from ditto suits and pocket watches (first inning, late 1800s) to three-piece sack suits (a couple innings later, at the turn of the century) to two-piece sack suits (the ’40s and ’50s) to jeans and sneakers (sometime around 1975). Uniforms progress from laced pullovers to guys in ties to baggy, hitched pants to tight. Players evolve, donning beards and then mustaches, going for clean shaves and then stubble, and back to curly mustaches again. None of this is discussed much. The film wisely targets the sport’s lore and its relation to race, focusing as much on Negro leagues and black baseball at its height as the Major League product. (It’s an approach that has held up well: The film’s comparison of Jim Crow laws to Nazism, criticized as “dubious" then, is scholarship now.) It’s also a work that shows how style, even within the relatively stiff confines of a tradition-heavy sport, traces time, from the hardscrabble fashion at the turn of the century to the 1970s’ free sideburns and plaids.

Michael

Burns displays a lighter touch here than most baseball films: Pictures tell the story and fashion inflects it, leading to a lot of rewindable moments, both on the field and off. In one scene, Willie Mays wears a banded shirt and billowy pants to play stickball on his Harlem block with neighborhood kids. Mays said doing so helped him hit the curveball, but he also looked good: His fit, billowy and minimal, looks like something from Margaret Howell’s line this season. In another scene, set in the ’50s or ’60s, revolutionary MLB Players Association leader Marvin Miller sits with his United Steelworker contemporaries, sometime in the ’50s or ’60s. His buddies wear loose shadow plaid jackets, while Miller, whose transformative efforts heading the MLBPA secured collective bargaining, neutral salary arbitration, free agency, and a healthy pension fund (and then some) for its players, is in a rounded suit, smiling. It’s a more arresting image than anything I’ve seen on Instagram this year—and an unspoken assertion by Burns that Miller, a man apart, sharp and smart, was the right person for the job.

Giants like Jackie Robinson and Miller helped baseball progress; its fashion, though, has a weirder, and less linear, timeline. Suits start at loud, become simple and then gaudy; uniforms go from blousy to tight to loose. Trends come, go, return, and then stay. Sweaters from the 1930s, big, bulky, and perfect for October, disappeared ages ago and have yet to be improved upon. (They are sort of available now, from Stone Island and Loro Piana, but not really.) An 1870s ballplayer’s jersey shares a font with a Nike line from a century later; a mid-1950s jersey with a zipper down the middle resembles a Neighborhood collaboration from a decade ago. The back-and-forth makes sense. Baseball’s by-the-book uniforms are perfect canvases for the subtle variations—a zipper here, a serif there—that fill out a century’s worth of looks. The small tweaks to the system of pants, shirts, jackets, and shoes that get worn off the field aren’t that different.

Washington Senators

But the film’s most consistent—and surprising—stylistic tic lies outside the lines. An assortment of nattily dressed baseball writers, general intellectuals, executives, and athletes—mostly men—populate the film, interviewed by Burns and his codirector, Lynn Novick, in their homes and offices. (There’s an old saw about sportswriters who dress poorly; Burns might have heard it and picked the ones who didn’t.) They discuss the sport at length, mostly in single outfits the whole 18 hours, creating images that stick. Burns conducted the interviews a couple years before the film’s 1994 release, and the mid-career professionals he talked to dress of their era and class, in mostly traditional office style. Nearly every writer seems to wear an oxford shirt: under a tie and houndstooth jacket for The New Yorker’s Roger Angell, striped with a red one for The Washington Post’s Thom Boswell. Tieless with a gold-button blazer for Boswell’s colleague George Will, who tells me the oxford was either Brooks Brothers or J. Press. Studs Terkel, Will’s spiritual opposite on all things but player compensation, has on a red checkered one, and a jacket. Shelby Foote, held over from Burns’s Civil War doc, goes without, as does John Thorn, the sport’s historian. Dan Okrent, an editor and author who invented both fantasy baseball and an advanced stat, is enough of a presence in the film to get two outfits, neither oxfords, though his main kit caused enough of a stir that Tony Kornheiser called it out in a column: “Memo: Somebody tell Okrent to change that sweater already.” Okrent told me the sweater was Land’s End and cotton, though he doesn’t remember what brand of glasses he wore, or Burns’s outfit. (Will remembers Burns wearing jeans.)

Not everything from the film holds up as well: Billy Crystal is present throughout, and later innings are clumsy on labor, assigning a false equivalence between players and ownership. Mostly, though, it covers what’s important very well and, in the process of shoring up a century of sport, makes a case for dressing nicely, or at least with intent. Nearly everyone Burns sits with and covers, whether or not they can hit a curveball, has on a shirt and tie, or a collared shirt; the more casual wardrobes in the film are just as slick. The outfits here are workaday, and effortful, the dress code of yore—a little extra, even though you don’t have to—hinted at in this New Year’s resolution. It’s a way of dressing that, over time, jumps off the screen as much as that bright Navajo sweater. We can’t wear finery to the ballpark, but a stay-at-home oxford seems like a happy compromise.

Oakland Athletics

After the bottom of the ninth come extra innings; there Burns reflects, and the sport gets its capstone. Donald Hall, the poet, helps set it apart. Over “the space of America and the time of America,” he says, baseball continues, allowing memory to gather. Right now that’s a half truth, with opening day up in the air. (“No one knows; anyone who tells you they know is lying,” a baseball person tells The Athletic about the 2020 season’s start.) Hall’s baseball, though, is a place we can return to, a thing we can “imagine existing in the future.” Right now it’s only that. Luckily, we can also look to the past.

Originally Appeared on GQ