What keeps Boulevard Brewing running? Beer biologists, peach rings and a sensory room

Inside Look is a Star series that takes our readers behind the scenes of some of the most well-known and not-so-well-known places and events in Kansas City. Have a suggestion for a future story? Email our journalists at InsideLook@kcstar.com.

A room at Boulevard Brewing Co. reminds me of my high school chemistry class.

Microscopes. Test tubes. Cryogenic freezers and machines I have no business describing without further research because I’m unsure what they do. Not quite what I was expecting while visiting the brewer compound off Southwest Boulevard and West 25th Street.

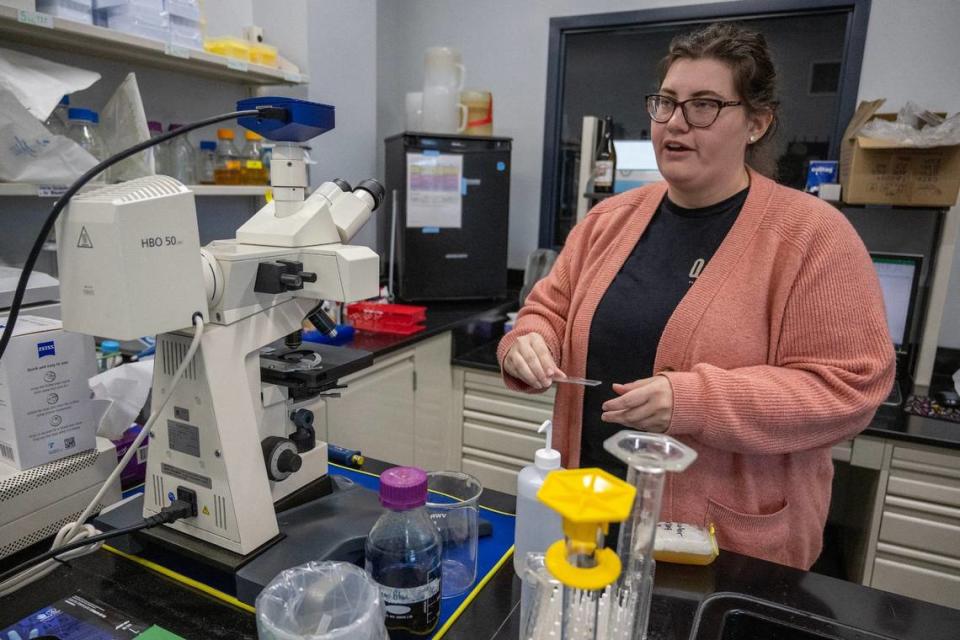

Michelle Williams, who has a Ph.D. in microbiology, holds up a liquid sample.

“It’s a lot of the basic principles of microbiology we’re using in the lab. … I just had to learn the brewery-specific knowledge,” Williams says.

You won’t get to walk around the lab if you book a tour with Boulevard. Too much expensive equipment, I realize, as I become hyper-conscious of my elbows.

A couple lab technicians click through glass microscope slides of beer at different fermentation stages. Williams takes us back to where they keep samples of yeast,frozen in glycerol at minus 16 Celsius.

“No gloves, no freezer,” she says.

I’m certainly no beer expert. As a restaurant and retail reporter, I’ve gotten to talk to my share of brewers in the year-ish I’ve been doing this. Most breweries contain a handful of tanks, lined side-by-side in a medium-sized room. But Boulevard — a company that churns out about 150,000 barrels of beer a year (a barrel is approximately 31 gallons) to 45 states and several countries — is no small-scale operation.

I’m reminded of this fact as we climb up several stories of winding stairs to get to the top of a fermentation tank, which holds 300 barrels of beer. There are more tanks outside, some bigger than this building.

A few days earlier, my colleague, photographer Emily Curiel, had mentioned wanting to tour Boulevard’s brewing campus. (Even if you’ve never visited Boulevard, you’ve likely noticed its brick smokestack towering over Interstate 35.) We reached out and were promised a true behind-the-scenes look — the kind where safety goggles are required.

How’s it made?

Tour guide and brand manager Adam Hall leads us over to a brick building, built in the late 1860s and once operated by the railcar maker Pullman Co. He parks himself behind a bar and tells us the story of John McDonald, who founded Boulevard in 1989.

McDonald toured Europe, tasted a variety of brews and was inspired to begin home brewing.

“He really gained some notoriety as this guy who’s brewing some really awesome beer,” Hall says. “Eventually, those people were like, ‘We encourage you to take your hobby and make it a career.’”

Today, Boulevard is a popular destination for beer drinkers, offering tours, event spaces and dozens of brews on tap.

Hall reaches down by a mill and cups the first ingredient of beer in his hand: barley. (Other types of grains can be used, too, like oats or wheat.)

The milled barley moves into the mash tun, where hot water is added. It’s then transferred to the lauter tun, a stainless steel machine that will filter liquid wort (a sugar-water mix) and extract additional sugars through a process called sparging. The wort is then shot into a boil kettle.

Hall called the mixture “sweet barley tea.” Hop pellets, a mashed up version of the flower, are added in to give it a bitter, piney taste. He shows us into a freezer, where I sniff a bag at a distance and feel my nostrils tingle.

The boiled “tea” is then transferred to fermentation tanks, where it’ll sit anywhere from a few days to a few weeks. The yeast samples Williams showed us will be introduced and eat away at the sugar, turning the now-chilled mixture into alcohol.

“As the yeast eats the sugar, it creates what we love most about the beer, which is flavor,” Hall says.

While the beer ferments, the lab will take samples, running them through a machine that will determine its exact alcohol level.

Deep in one of the brewhouses, we walk past steel tanks and through rooms filled with zigzagging pipes, and innovation brewer Greg Garrity gestures toward what looks like an old switchboard. Dozens of levers direct the liquids into each tank. The pipes carry wort, water and grist.

“We have sort of this lazy river of chemicals flowing through the brewery,” Garrity says.

Experimentation is key

Prepare to be jealous of Garrity’s job. A large portion of his time is spent creating new beer and Quirk recipes for Boulevard — a lot of Quirk lately, he adds, since hard seltzer is all the rage.

He lets us sample a couple of his experiments: The first is a beer flavored with chamoy and peach rings. Yes, he threw actual peach ring candy into the fermentation tank to give the drink its sweet, puckery flavor.

He turns the spigot and the new brew — which will be offered for a limited time at the upcoming Boulevardia festival — spills into our cups. Emily and I sip and agree: very tasty.

The next drink is a blood orange beer, which comes out a dark maroon. Another sip, another hit for both of us.

The beer’s clarity is determined by a centrifuge tank. Inside, conical disks spin and separate the “chonky” sediment, as Hall described it. The faster the disks spin, the clearer the beer becomes.

So, what’s better? Hazy or clear? It’s more of a preference thing, Hall says.

“Think of a hazy IPA,” he says. “The yeast is going to produce a lot of flavor and a little bit of body … like O.J. with pulp and O.J. without pulp.”

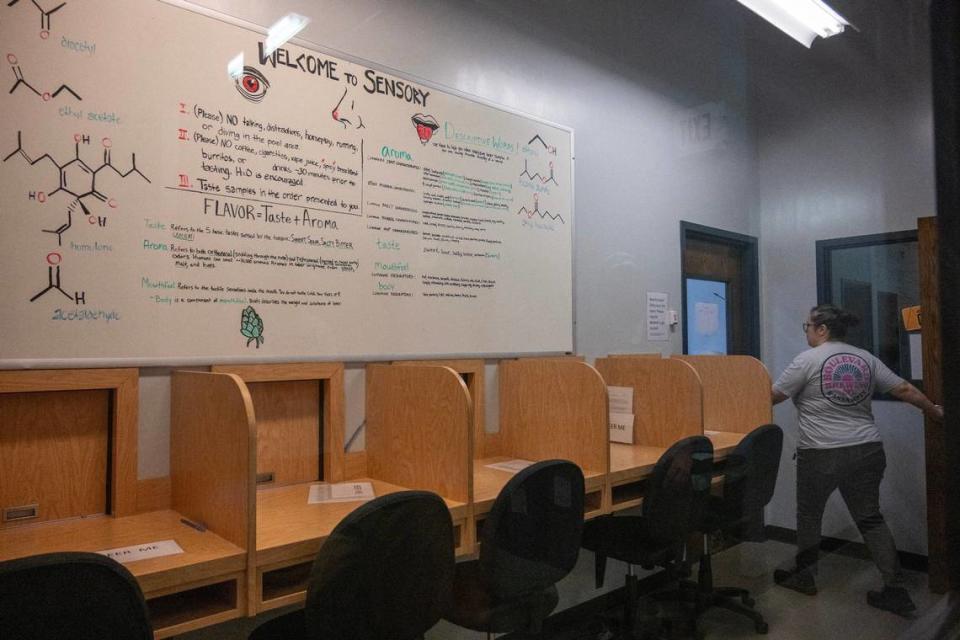

Before Boulevard can send its beer off to the public, it’s subjected to blind taste tests by staff members, who are also given cups of beer tainted with “off” flavors to make sure their taste buds are sufficient.

Hall showed us the taste-testing area: a small room behind plexiglass with little windows and dividers. Here, a small group of the campus’s 250-plus employees will grade the beer on appearance, smell and taste.

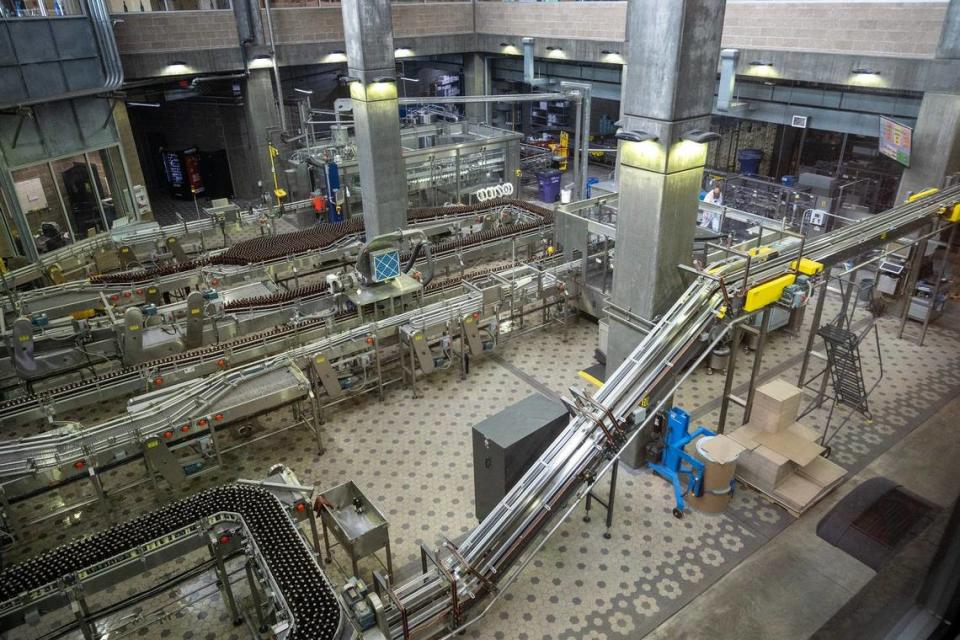

Once the beer is deemed fit for customers, it’s sent to be bottled. Hall walked us past an expansive room with a winding network of conveyor belts, where machines fill rows of bottles and cart them off to another area. The filled bottles are sealed into boxes.

Another employee perk: All the mis-packaged products (dented, not filled all the way, etc.) are placed in a pile in the packaging room for anyone to take home at the end of the week.

“If you work here, Friday, end of the day … you come by and you always have some beer ready to go,” Hall says.

One thing’s clear after touring nearly every inch of its facilities: Boulevard is proud of its Kansas City roots.

A staff photo on a wall shows dozens of smiling employees holding beer cans and wearing KC-themed tees. Boulevard partners with several local businesses and organizations, releasing the “blueberry slam” Quirk seltzer for the Royals, and the “celly” juice (seltzer) and Teal Rising Proud Pilsner in partnership with KC Current.

“You walk around downtown and you’re like, ‘Man, is there a sporting event today?’ Everyone has a shirt that has ‘Kansas City’ on it,” Hall says with a laugh. “Kansas City, above all things, the one thing they love the most is Kansas City.”

In a sense, Boulevard is always wearing its “Kansas City T-shirt,” too.

“KC really embraced Boulevard,” Hall says. “… We grossly underestimated how thirsty Kansas City was.”

Want to visit?

▪ Tours: Boulevard, 2534 Madison Ave., offers four types of brewery tours. For more information and to buy tickets, visit boulevard.com/visit-us/tours. Pricing varies based on the tour.

▪ Hangouts: The brewery’s recreation hall offers quick bites, beer flights and activities from noon to 8 p.m. Mondays through Thursdays, 11 a.m. to 9 p.m. Fridays and Saturdays, and 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. on Sundays. Boulevard also offers five spaces for events. See boulevard.com.

▪ Festival: The brewery’s Boulevardia music festival will run June 14 and 15 at Crown Center. Tickets are on sale now, but the music lineup has yet to be announced.