A Kansas City legacy: Railroads, romance and the restaurants that refined the West

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Uniquely KC is a Star series exploring what makes Kansas City special. Are you feeling nostalgic for a Kansas City area restaurant that closed years ago? Share your memories, and we may write about the place in a future story.

For the last few decades, the east side of Union Station has housed Kansas City’s Chamber of Commerce.

But outside its door, a display of century-old fine china tells the tale of the space’s original occupants: Fred Harvey and Union Station’s first visitors. It’s a story of resettlement, a railroad dynasty — and romance.

Fans of Judy Garland may remember her 1946 film, “The Harvey Girls,” in which she played a doe-eyed waitress at a Harvey House restaurant.

Much like Union Station’s real Harvey Girls, Garland’s character wore a crisp, white apron and served customers traveling along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway. (Cue Garland’s song.) In their heyday, Fred Harvey’s restaurants were the emblem of the modern world.

As humorist Will Rogers once said, the Harvey Girls “kept the West in food — and wives.”

Kansas City’s own Harvey House restaurant operated from Union Station’s 1914 opening until New Year’s Eve in 1968, when the Harvey company was sold to sugar cane company Amfac Inc.

A reporter for The Kansas City Times, The Star’s sister paper, wrote at the time that the restaurant’s closing marked the “end of an era.”

In 1876, freight agent Fred Harvey of Leavenworth noticed a major problem with railroads. While more passengers were climbing aboard, the food options at stations were abysmal: Think canned beans and cold coffee.

“The stations really didn’t have those kinds of amenities,” said Denise Morrison, curator of the Kansas City Museum. “Harvey saw an opportunity to open a restaurant in the station or open … next to the station.”

He opened his first Harvey House restaurant in Topeka that year to great success and went on to open up more along the line, which snaked southwest from Chicago.

Harvey was notably choosy about who could work at his restaurants. The waitresses could only be young, single women. The Kansas City Times noted in 1966 that the women had a “uniquely attractive appearance.”

And while Kansas City’s restaurant did not require the young women to live in boarding houses, most early Harvey House restaurants did.

“It was genteel,” Morrison said. “It took away kind of that Wild West atmosphere.”

The Harvey Girl lifestyle was considered a privilege. Good pay, an opportunity to travel, and love, perhaps. In the late 1800s, the young, beautiful women often linked up with the rugged cowboys along the wild frontier, which lacked the single ladies that the East had to offer.

The Associated Press noted in 1966 that a rumored 20,000 Harvey Girls married Western ranchers, cowboys or railroad men.

Union Station opened a few years after Fred Harvey’s death, and it became the headquarters for the Fred Harvey Co., run by his son, Ford Harvey. The world looked different in 1914 than it did in 1876, but the Harvey Girls were still a hit.

At 18, Eunice Coffee of Eminence, Missouri, became a Harvey Girl in 1929 — one of more than 100,000 at the time. She and her cousin applied fresh out of high school.

“We decided we needed a little adventure in our lives,” she told The Star in 1993.

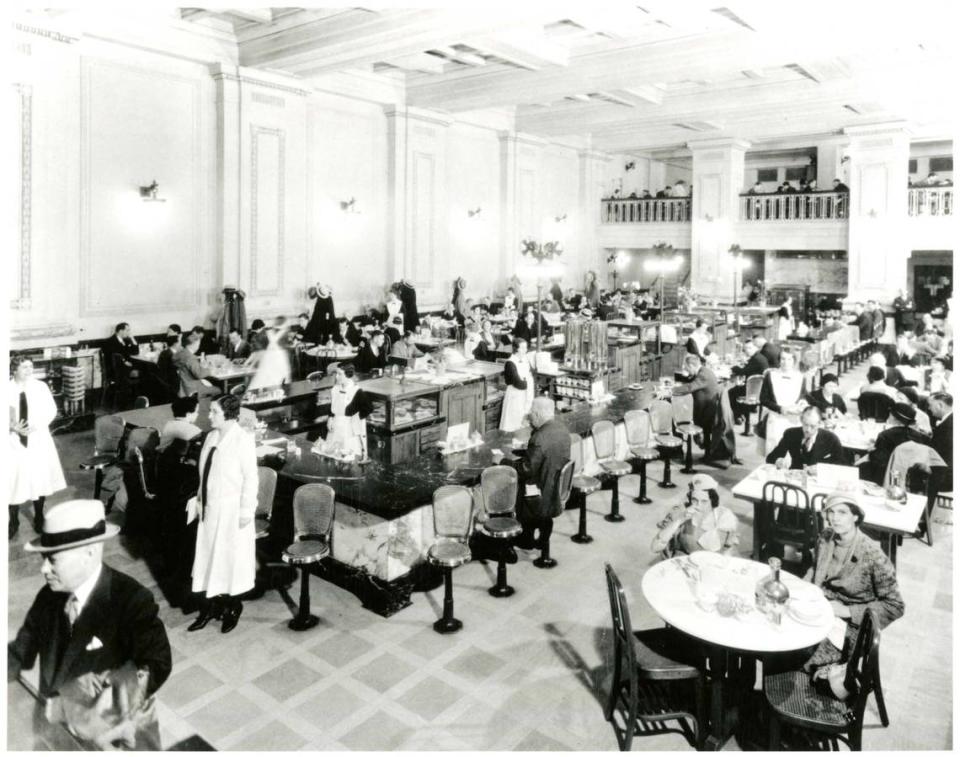

Kansas City’s Harvey House restaurant seated 300 diners. In 1936, an additional dining room was remodeled and called the Westport Room.

“That’s what most of the oldest generation remembers,” Morrison said.

As time went on, Harvey Girls were eventually permitted to marry and wear wedding rings. The uniforms became more modern, changing from black and white to pink.

After the Harvey company ceased operations in 1968, the space went on to house the Colony and Lobster Pot restaurants.

“It is with sadness that on this December 31 at midnight, customers and longtime friends of the restaurant will see the name ‘Fred Harvey’ disappear forever from the Union Station,” The Times reported at the time.

Though the writer’s prediction was not entirely true.

Today, a restaurant called Harvey’s stands in Union Station’s Grand Hall, across the way from Pierpont’s. Its name pays homage to the legendary freight worker and his restaurant.

The circular restaurant, once home to Union Cafe, opened in 2011.

It’s similar in spirit to the Harvey House, aiming to serve quality food to travelers, or, perhaps more likely now, anyone passing through. But it’s void of cowboys.

No waitresses singing Johnny Mercer tunes while they juggle plates, either.

“Here we are, going all the way, mustn’t quit till we hit Californ-I-A.

On the Atchison, Topeka and the Santa Fe.”