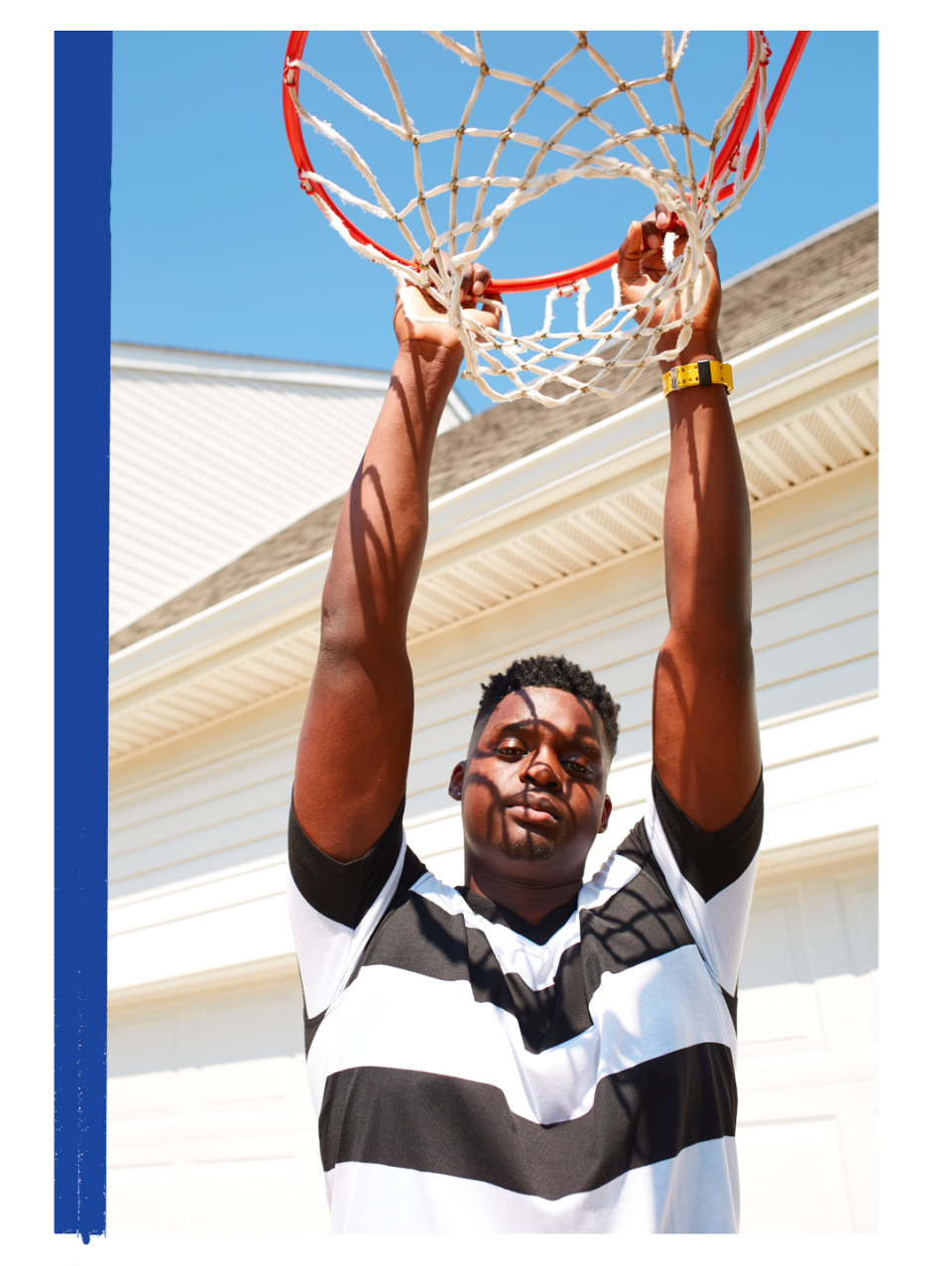

Kalin Bennett Plays Division I Basketball. He Also Has Autism.

This story is part of The 2020 Project, a Men's Health special project that explores the lives of 20 different 20-year-old men across America. To learn more about the others, go here.

BEFORE GAME TIME, he Kent State men’s basketball locker room is usually charged. Music blasts. Athletic tape tears. Teammates shout and whoop. But Kalin Bennett, the team’s six-foot-eleven-inch center, is quiet. He’s scrutinizing the game plan. He’s running game footage in his head. He’s flitting through where every player might be on the court at any point throughout the game.

It’s the same preparation that helped Bennett push Little Rock Christian Academy to a winning 2018 season. It’s the same prep that helped him nail a clutch left-handed hook shot in his debut game for Kent State in 2019. And it’s the same prep that’s furthering the understanding of autism not as a disability but just another way that brains can work.

Bennett is a person with autism, also known as autism spectrum disorder (ASD), a range of developmental issues that can affect communication and socialization. His mother, Sonja, realized that her son was different when he was one. “He wasn’t focusing on me and didn’t want me to hug him,” she says. “He just wanted to sit in the corner and rock.”

In 2008, the prevalence of ASD in eight-year-olds was one in 88. By 2016, it was one in 54. The increase may be due to more doctors learning the criteria, says Zoe Gross, director of operations at the Autistic Self Advocacy Network.

When doctors diagnosed Bennett, Sonja says, people told her that he needed to be “institutionalized” and that she “needed to understand he will never do this, never do that.”

While it’s still unclear what causes ASD—genetic factors may play significant roles—Gross says that girls, women, and people of color are “underdiagnosed.” ASD is no more common in white children than in their Black and Hispanic peers, yet Black and Hispanic children are often diagnosed later, due in part to a lack of access to ASD experts. This delay may result in missed opportunities for therapy, which can affect long-term quality of life.

Sonja found a pediatrician who recommended therapy programs, and she developed other strategies herself, until her son could talk, which he did at age seven. When Bennett was eight, he watched the 2008 NBA Eastern Conference semifinal matchup between the Boston Celtics and the Cleveland Cavaliers. “I saw LeBron James going for a dunk, and I said, ‘I can do that; I wanna do that,’ ” he says. There’s a saying in the Bennett household: “Can’t is not an option,” says Sonja. And so Bennett’s older sister, Kay, began to play basketball with him. “[My family] gave me a chance,” he says. “They had my back from the very start.”

Until two years ago, he didn’t talk much about being someone with autism. Part of that, he says, was because he didn’t understand it himself. When he first began playing on a team, in 2014, Bennett was “in his shell,” Sonja says, and not comfortable with his Arkansas Hawks teammates. But he was comfortable with the ball and had a knack for free throws and blocking. He also had a knack and a love for math, and his coach at the time figured out how to communicate plays to him with numbers—a method Bennett uses to process the game today.

Then one fall night in 2019 at Link Year, a gap-year Bible program between high school and college, Bennett shared his story with his teammates. He chose to include his autism in the narrative. “They embraced me so quick,” he says. “They never stopped supporting me.”

Since then, Bennett has established the SpeKTrum50 Foundation (50 being his Kent State number, and his favorite number since third grade) to advocate for a greater understanding of autism. He’s set up ktech50.com, assembled a board of directors, and led a meet and greet with three school-aged autistic basketball players in his home state of Arkansas. “I want to help kids who are different to not feel different,” he says.

“Me, as a 20-year-old, I’ve matured a lot,” Bennett adds. “I love who I am. I might have autism, but I love that part of me.”

You Might Also Like