How Justin Cronin Wrote the Ultimate "Holy Sh*t" Moment

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

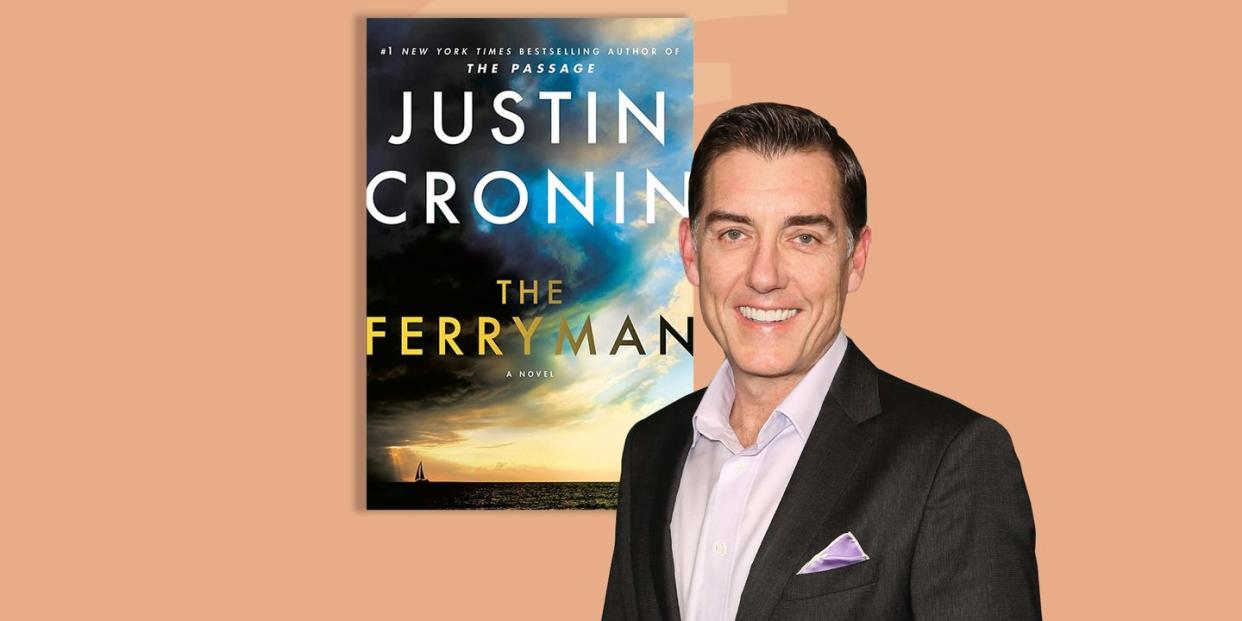

Justin Cronin has no ideas where his stories come from. When asked, he talks about the “deep stew of the unconscious mind” and credits a creative writing teacher who told him his job as writer is “to be sitting at his keyboard when the story comes from above.” Cronin offers anecdotes and recognizes inspirations, but he’s honest about the true mystery that underpins his work. More than honest, in fact: his novels actively try to unpick that secret, and to answer questions about the origins, impact, and longevity of human storytelling. His mega-selling trilogy, The Passage, may be a mixture of vampire horror, apocalyptic science fiction, adventure novel, and western, but at its thematic heart, it’s a story about how stories come to be more than story. You could say it’s about how religions are born.

Cronin completed the trilogy in 2016 with The City of Mirrors. It concluded a remarkable feat, a trilogy Stephen King called “one of the great achievements of American fantasy fiction.” Nearly a million words in length, spanning centuries of human struggle, with a huge cast of characters, it understandably left the author “pretty spent.” Rather than dive directly into another book, he opted to wait, “to see what would rise organically” in his imagination. What eventually did appears at first to be a very different novel from what came before.

According to the author, his latest release, The Ferryman, is “a thriller, a detective novel, a conspiracy novel, and speculative fiction in the tradition of golden-age sci-fi.” The book welcomes us to Prospera, an island state curtained off from the rest of a devastated world. Proctor Bennett, in his role as Ferryman, is tasked with escorting Prosperans to their “reiteration.” You see, in this urban idyll, no one truly dies. The elderly, infirm, and unhappy take a boat trip to the Nursery, where memories are wiped, bodies are renewed, and life begins afresh. Of course, anyone with even the most cursory understanding of genre fiction understands immediately that nothing is as it seems. Following a troubling encounter with his own father, Proctor is propelled on a journey of discovery with existentially explosive stakes.

The gleaming, anodyne Prospera is a universe and a few genres away from the apocalyptic grunge of The Passage, but Cronin’s fascination with time, truth, and the telling of tales has not dimmed. It’s impossible to expound further without giving away some of The Ferryman’s most WTF revelations, of which there are many. In fact, this is the kind of book that turns an interview into a razor-wire tiptoe between spoilers. During an hour-long conversation, Cronin and I worry about how much we can divulge without ruining the magic trick. We erred on the side of caution.

Everything in the end, though, comes back to the principles of story. And about that Justin Cronin has a lot to say, even if he’s still not sure where the spark really comes from. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

ESQUIRE: You spent a decade writing The Passage. Did it feel odd to be working on a new book, after spending so long writing in the same universe?

JUSTIN CRONIN: All writing feels in some way the same, because your job is always the same: to be interesting and to create psychological plausibility in whatever scenario you are working with. I’ve always put the characters first and I think about them in terms of the truth of human complexity. That’s always my first position. But in The Ferryman, I no longer had the luxury of having my characters running for their lives every minute of the day. In The Passage, mortal peril on the daily is the basic circumstance of the entire trilogy. It’s a great characterization tool, because if people are running for their lives, they can’t help but be themselves. Whereas, with The Ferryman, matters of plot and character relied on much more subtle effects.

$25.48

amazon.com

Was it an intentional gear shift? A chance to tell a different kind of story?

I’m not a very tactical careerist. I think you should write the book that’s asking you to write it. I’m also a pretty slow writer and this was a tricky book to write, because it relies on a big reveal. You’re supposed to come to a moment in this novel that makes the top of your head blow off. Making sure that I earned that right was a complicated matter. I did draft after draft to make sure things lined up.

Yet, as different as The Ferryman and The Passage seem, both are arguably about how we mythologize the past to understand our present.

Yes. The Passage is about how, over time, a human story becomes the foundation for cultural meaning. It doesn’t matter whether you call that religion or mythology or pedigree; there were ordinary people in the past that became larger than life and imparted meaning to societies. An easy example for you, as a Brit, would be King Arthur. In reality, he was probably a bad-smelling guy who lived on a dirt hill, but who was pretty good at forestalling some of the Anglo-Saxon incursion and giving Celtic culture a toehold to survive. But he was just a guy. The Passage takes up that question for a religion of the future, a thousand years down the road. In The Ferryman, the question of “how will this be remembered” becomes quite explicit. I’m delighted to hear that you noticed that link.

Is that something you’re interested in? How story functions across large expanses of time?

In some ways, it’s a personal concern. I recently turned sixty, which was a shock! It occurred to me that, for my children, the unbelievably quaint and primitive world of my parents’ childhood, in the 30s and 40s, is the same as my own childhood in the 70s. We are always somebody’s past. As time goes by, the deeper that past becomes. As I’ve gotten older, that’s become a matter that interests me, maybe obsesses me deeply. You get a feeling for how you’re being shuffled off-stage, as one day my children and their children will be shuffled off-stage. As I was writing The Passage and The Ferryman, I was thinking about how any human life is just this tiny flash in the vast sweep of time, both past and future. It’s the occasion for great humility, but also wonder.

And there is wonder in The Ferryman. For all its thrills and existential crises, it left me with such hope for the future.

It’s supposed to. The other day in an interview, I was asked what was the dominant emotion I wanted the reader to feel. My response was awe.

Do you have any clear idea on how or why the sheer scale of the story occurred to you?

Where it came from is one of those great mysteries of the subconscious and the imagination. But I do remember what happened. I was taking a walk on a pretty, starry autumn night in Cape Cod and two things happened in rapid succession. First, a word dropped into my head. It was a word I didn’t know and it seemed to come from nowhere at all. That word was oranios, which becomes the open sesame word of The Ferryman. In the book, once you hear that word, you’re in trouble and you are trouble. At the same time, a scene landed in my head of an elderly man on a pier, having some kind of psychological meltdown. The word and the scene seemed to have something to do with each other, but I had no idea what. I had to marinate in it for a while, and really, what I was doing was waiting for a third idea to collide with them. That’s usually how my books come about: things that don’t seem to be connected have a collision that spawns a new thing. I can’t tell you what that third thing was, because that’s the big reveal.

What about other influences? The novel feels so firmly part of the canon of science fiction going back over the last four or five decades. I can see Logan’s Run, Soylent Green, Total Recall, The Matrix, even The Truman Show. Are there specific texts that influenced you?

Yes to all of the stories you mention, except for The Truman Show, which I haven’t seen. Everybody is comparing my book to that movie and I need to go watch it now so that I can get the reference. But everything else you mention was absolutely a foundational text for me growing up. I was born in 1962, so I became a reader in some real way in the 1970s. Soylent Green especially was part of the holy triptych of bare-chested Charlton Heston sci-fi movies of the era. The others are The Omega Man and Planet of the Apes. Come to think of it, I’d add Planet of the Apes to your list of references. There was the novel by Pierre Boulle, but the original movie was probably the most important text of my childhood. That movie did something that The Ferryman is intended to do. There’s a moment when, retroactively, everything in the story suddenly makes sense in ways you did not realize. That’s the kind of moment I wanted to create. I always wanted to write the ultimate holy shit moment when the reader throws the book across the room in a kind of pleasure.

$16.98

amazon.com

Here's a comparison you may not have heard before. The book that The Ferryman most reminds me of, though it has very little in common plot-wise, is Kazuo Ishiguro’s Never Let Me Go.

Give yourself a raise. That was absolutely on my mind; when I sat down, I thought, “I want to do this how Ishiguro would do it.” First of all, he’s a very rich stylist, and he brings a tremendous virtuosity to language. Also, if you look at Never Let Me Go and Klara and the Sun, they are both first-person narratives by people who live totally inside systems which are exotic to us, but totally ordinary to them.

What all of these referenced stories have in common is a tension between truth and lies, or a misconception of reality. That’s at the core of The Ferryman, too. Do you find that uncertainty a frightening idea?

Yeah, it’s the most unsettling thought you can have, either personally or as a culture. What is the universe composed of? What is reality? For centuries we had religions to answer those questions for us, but the deeper we go into science, the stranger reality becomes. It wasn’t too long ago that people introduced the idea that everything is a simulation. Which is a disturbing idea that’s given rise to books like Emily St. John Mandel's Sea of Tranquility. For me, the most unsettling concept is infinity. The idea of everything all at once, everywhere, in every direction. That’s a great name for a great movie, but even as a child, it’s an idea that settled on me as a source of acute anxiety.

Does that anxiety stem from you being a writer? After all, infinity is a limitless space to fill. Eventually, that must force you to confront the limits of your imagination?

Maybe. Most writers are trying to fill a void, to find patterns. Life feels generally unpatterned. It’s poorly organized and doesn’t give meaning very easily. Most of life is picking up dry-cleaning and standing in line at the movies. Writers and creative people, I think, have an additional impulse to put life in order. To reach conclusions about things. Stories have beginnings, middles, and ends, and human lives do too, but often the ending feels arbitrary. Human lives generally feel like poorly written novels.

Among all of the elements you imagine to fill the world of The Ferryman, perhaps the most chilling is the health tracker that each Prosperan has embedded into their arm. If their wellbeing drops below a certain quantifiable degree, they are forcefully reiterated. It felt like a comment on our current rejection of illness and unhappiness as in some way “wrong.”

Completely. There is no art without suffering; there is no joy without fear and loss. The contrapuntal nature of existence, the opposites sitting side by side, is the source of life’s bittersweet beauty. In Prospera, they all have this thing that they can plug into that tells them about wellbeing. It tells them they are experiencing life in the fullest manner, when of course that’s the exact opposite of what they are doing. No one wants tragedy, pain, and sorrow; it’s no fun. But let’s imagine a world in which we manage to banish all those things. Wouldn’t that be a dead world? What kind of life is that? Easy, I guess. But it doesn’t seem to be a life that feels truly rich and enriched by the collision of opposites. In the current vogue for self-care, the word “self” is the biggest word. If you emphasize that word a little more strongly, the entire phrase is revealed as maybe a little bit repulsive.

Among the very high concept plot architecture in the book, how important was it to maintain the focus on humanity?

Yeah, the machinery can be a bogeyman. A book with a cool gizmo is fun; I really do like gizmos. I love time travel and monsters and apocalypses, but often cool gizmo books are a brief joy and then you put them aside. A book with humanity is more easily absorbed into memory. I want to entertain, sure, but the way that I relate to books has always been about asking the book to help me understand my life.

That’s interesting, considering you’ve written a book from the point-of-view of a character who understands almost nothing about the reality of his own life. Did you know where this was going when you started?

The most important thing for me when writing a novel is knowing how it ends. If I know how it ends, I can organize everything in the story towards that end, often working towards the final line itself. The Passage trilogy, for instance, was nearly a million words, but it wasn’t long after I started the first book that I was standing in a supermarket parking lot when the last sentence of the whole thing dropped into my head. Not just that last scene, but its actual language. For seven years, I wrote towards that sentence.

I learned that principle from a guy who told a great joke at a writers’ retreat. I was new to this group and everyone was saying to this guy, “Tell the goat joke”. He told it and it was hilarious, but across the length of the week, I heard it several times, and each time it was a little different. The reason he could do that—and still tell the hell out of it each time—was because he had the punchline. He was the local god of the joke and he knew where it was going. To some extent, this is the subject of The Ferryman, that reality needs an author. It can’t just be arbitrary. It needs a local god, an intelligence presiding over it.

And what about your life? Would you rather live in a world of happy misperception, or are you committed to the cold, hard real?

Oh, give me an analog world. I’d be happier in it I think. Actually, no, I’m quite sure I would. I’ve reached a point in life where capitalism is interested only in my ability to buy pharmaceuticals and financial products, so I’m just going to lean in.

You Might Also Like