Juneteenth and Black America’s Love of Horses

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

Each year, Black people across the United States observe June 19—the day in 1865 when thousands of formerly enslaved people in Galveston, Texas, learned of the Emancipation Proclamation. And each year on Juneteenth, Black cowboys throughout Texas saddle up for the rodeo. In places like Longview and Dallas, Henderson and Forth Worth, Black equestrians display their prowess as bareback riders, barrel racers, and steer wrestlers. Often accompanied by food and music, these events, echo the celebratory atmosphere found in many Black communities on the holiday. They are also a reminder that horses are intimately tied to the histories of Black freedom and survival at the heart of Juneteenth.

Many states, including my own, have less recognized emancipation dates, whose histories provide important localized context about the Reconstruction era. But Juneteenth—although belonging first and foremost to Black Texans—has spread to Black communities throughout the United States since its inception, becoming a nationwide day for historical reflection and summertime celebration. When it became a federal holiday in 2021—a development seen by many Black people as solely symbolic and failing to address the material demands of Black communities–Juneteenth entered the larger public imagination, becoming part of mainstream narratives about racial progress. In the face of this newfound visibility, it’s important to remember that Juneteenth isn’t just a simple celebration of freedom, but also a lesson that Black liberation is both hard-won and incomplete. This has been true from the start—the Emancipation Proclamation had been signed into law over two years before enslaved people in Galveston were told about it. Because it remains true, it is crucially important to engage with Juneteenth beyond pithy statements about opportunity and progress, and to see the fullness of what it is: a sobering and complex story about Black Southern survival and the white supremacist state that seeks to deny Black freedom.

In 1860, nearly 200,000 slaves lived in Texas, often tending horses belonging to white cattle ranchers, farmers, and speculators. Throughout the plantation era, enslaved Black people commonly worked as stable hands, horse trainers, jockeys, and grooms. Horses were used as colonial symbols of wealth and power, as well as for entertainment. To maintain their horses, white colonists relied on generations of Black labor and equine knowledge.

But although Black slaves were exploited for their expertise with horses, that skill set also offered opportunities for resistance. Countless 19th-century notices for escaped slaves describe them fleeing plantations on stolen horses. In former slave Lewis Clarke’s memoir, he writes, “I saddled my pony … put my clothes into a pair of saddlebags … and thus equipped set sail for the North Star.” For those who had access to horses, riding helped them evade capture, offered speed and mobility that could not be achieved on foot. A people transformed into commodity, riding with their fellow beasts of burden on the underside of freedom.

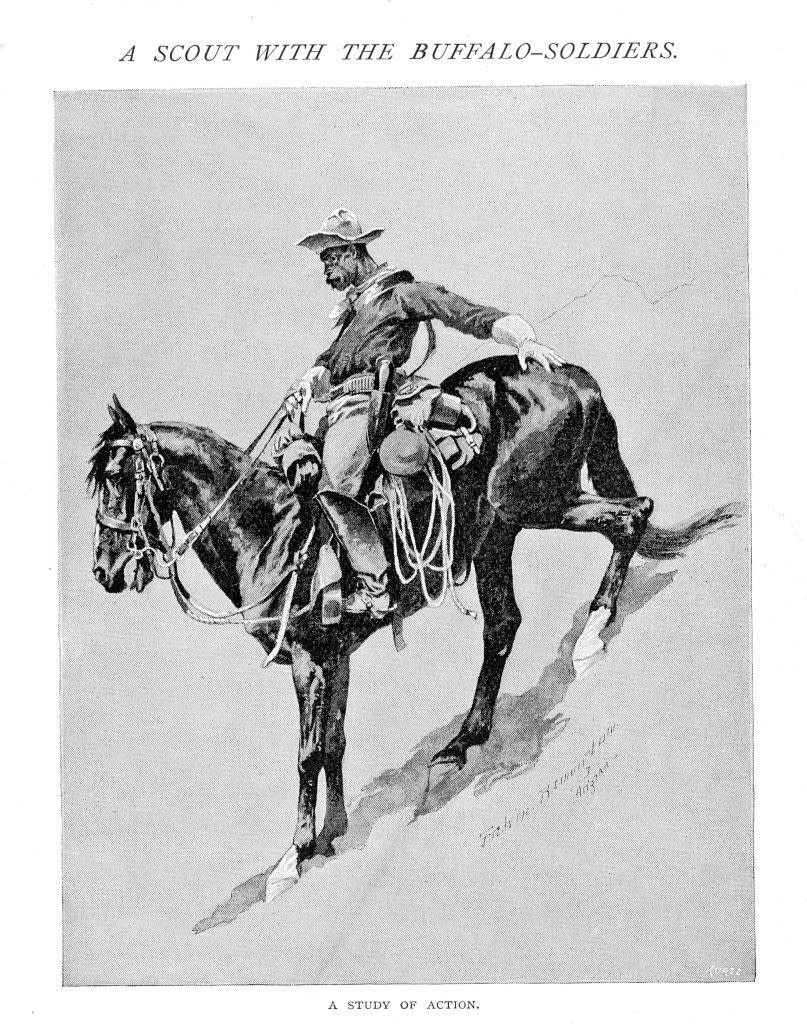

After emancipation, former slaves found work as cowhands, building the horse and ranch culture that became synonymous with the American West. While romantic depictions of Wild West Black cowboys abound, the story is of course more complicated—one in which the boundaries of agency, imperial conscription, and economic need are continually blurred. Black cowboys were Buffalo Soldiers deployed by the U.S. Army to defend white settlements and advance the cause of Manifest Destiny. Black cowboys were outlaws who built their reputations and lives on outrunning the respectable institutions of the frontier country. Black cowboys were underpaid laborers driving cattle on dusty trails across indigenous land. Black cowboys were women, sharpshooters who opened taverns and drove stagecoaches over the mountains. And Black cowboys were visionaries using their knowledge to build self-determined Black towns. In Boley, Oklahoma—an all-Black town founded by former slaves in 1905—residents organized an annual rodeo that is still in operation today. In its earliest days, the Boley Rodeo showcased the skill of the town’s riders while also serving as an advertisement for a place created by dreams of Black freedom.

Riding horses is a practice of being on the move, embodying an agility that challenges border logic—forbidden mobility, fugitive consciousness. It’s a practice and a politic that has echoed throughout the diaspora, from 18th-century Haitian revolutionary Toussaint Louverture’s renowned horsemanship to public protests against Black death across the U.S. to the everyday gatherings of riders in cities like L.A. and Philly.

To talk about horses and Juneteenth is to adamantly remember and take instruction from the survival strategies Black horse riders have been adopting and creating for centuries across America. It is to recognize the imaginative ways Black people have built spaces for the preservation of land-based knowledge, athletic skills, ancestral traditions, and political engagement. By learning about the history of horse culture and its importance to Black resistance, we can better honor the complex legacies and meanings of this day.

You Might Also Like