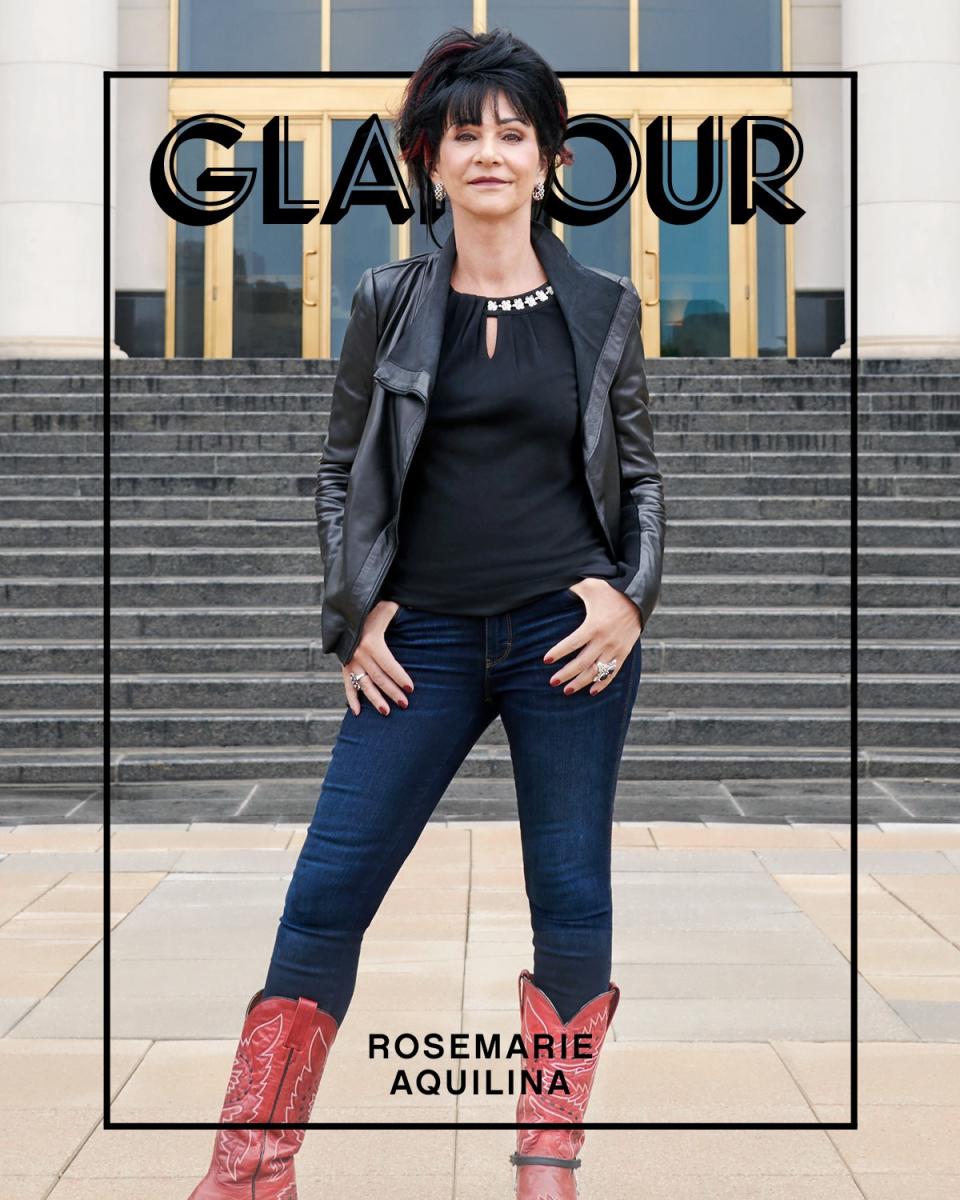

Judge Rosemarie Aquilina Isn’t Done Listening Yet

You can tell at first glance that Rosemarie Aquilina is no ordinary judge. The woman who spent 20 years in the National Guard and 14 on the bench telegraphs that with bold red streaks in her jet-black hair. “It’s really party in the back,” she says. “When I put my hair up, it’s my little independence. As a judge, we have to be so straight and narrow. Well, I’m not—in my life or in the courtroom. I don’t want to be put in a box.”

At the January 24 sentencing of USA Gymnastics doctor Larry Nassar, Judge Aquilina, 60, became an overnight sensation for letting the “sister survivors,” as she dubbed them, have a voice.

Where did she find that heart, that flair, that spine of steel? Perhaps it all started when she immigrated to America at age one, poor and without a country, her passport stamped “stateless.” It was 1959, and her mother, Johanna, brought little Rosie and her brother from Munich to Detroit to live with her grandparents. The elder couple cared for her while her mother worked at an insurance company and her father finished medical school back in Germany. “He’d visit, but I did not realize he was my dad,” says Aquilina. “I thought my grandparents were my parents, and my mom was this older sister who helped out. No one ever explained it to me.” When her father finally came for good and moved his family to their own home, she says, “I thought I’d been kidnapped.”

Judge-final-cover.jpg

She was five and devastated, and it took a while to sort things out with her family. “But that’s why I have been the voice for people in everything I do,” she says. “Why I have always listened. Because I was a little kid saying, ‘What are you doing to me? I want to go back home.’ And I wasn’t heard.”

After that, Aquilina spent much of her childhood standing in the corner, eyes to the wall, refusing to apologize or acquiesce to her father. “You can’t beat them in the United States, so you send them to the corner,” says Joe Aquilina with a sly chuckle, knowing full well how many child abusers his daughter has put away. “Rosie was bullheaded, and she had to do [things] on her own terms.” Her mother agrees: “She just questioned us all the time and wanted to do it her way.”

And that’s pretty much how Rosemarie Aquilina has rolled. She did it her way when she got married after college at Michigan State University (yep, she’s an alumna of the university where Nassar worked) and had not one but two babies during law school at Western Michigan University. She did it her way when she joined the Army National Guard and became the first female judge advocate general, or JAG, in Michigan history. She did it her way when she had twins at 52. And she did it her way at Ingham County Circuit Court when she let 156 survivors speak as long as they wanted so they could begin to heal.

Aquilina took her first job assisting then Michigan state senator John F. Kelly and later started her own family practice, Aquilina Law Firm. As a respite from her heavy caseload, she started writing crime novels during her lunch hour. (Her first book, Feel No Evil, revolves around a rape; the second, Triple Cross Killer, abused children. “I’d wake up at two in the morning to get my character out of trouble,” she says, and sit down to write.) She also joined the Army National Guard, putting in at least one weekend a month and a couple of weeks a year. “I don’t know when she ever really slept,” says Colonel John Wojcik, Michigan National Guard’s general counsel. “She is passionate with an unquenchable drive, and she has a good judicial temperament. I always found her to be balanced and fair regardless of whether I was prosecuting or defending a case.”

Then in 2002 she realized a few weeks a year as a JAG weren't enough. She was sitting with a court-appointed client in her private practice when something clicked. “This was a mother who beat her teenage daughter with a belt buckle,” she recalls. “I can still picture this girl. The bruises were so swollen, I mean, it was gut-wrenching. I said, ‘Look, you can’t do this.’ And she said, ‘That’s how I control her.’ I literally had to sit on my hands because I wanted to lean over and choke her. I thought right then: I need to be able to say, ‘You’re going to prison and here’s the treatment, here’s how to fix this.’ ”

And so in 2004, at age 46, Aquilina ran for the Fifty-Fifth District Court in Ingham County and won. She’s been on the bench ever since, having been elected to the county’s higher Thirtieth Circuit Court in 2008. From her first bang of the gavel, she has insisted on hearing from victims, their families, and anyone impacted by the crime “so I can get the full picture to make the best decision,” she says. And she’s always made sure they have a safe space to tell their stories: “When you ask, ‘What would you like me to know?’ it empowers them. They go, ‘Someone’s listening; let me talk now.’”

Aquilina is just as committed to hearing from the offenders and their families. “She was very good at allowing the defense attorneys to walk their cases through, even if they were kind of crazy arguments,” Col. Wojcik remembers, “so if the defendants [lost], they could look their lawyer in the eye and say, ‘Hey, you got to give it your best shot and the judge let me say my piece.’ That goes a long way.”

“In my life or in my courtroom, I don’t want to be put in a box.”

No one was more shocked at the response to the Larry Nassar sentencing than Aquilina. “After it was over, I took a break and went and did four probation violations. I had no idea that the world was exploding,” she says. “I just did what I always do.” In the crush of attention, she heard from other judges who charged, “You are a disgrace,” and, “How dare you behave like this?” for her rebuke of Nassar from the bench. Aquilina doesn’t care: “When I spoke harshly, I did it to deflate all that tenseness in the courtroom where I was afraid people were going to rush him.” The Circuit Court’s Chief Judge Richard Garcia agreed. “Judge Aquilina clearly understood the role of righteous indignation. She also understood the role of the court to have this emotion controlled by the judge rather than allow it to run wild in the community,” he wrote in response to Nassar’s first appeal. “This was a controlled burn.”

Critics have also argued that this victim-centered approach could turn courts into therapy chambers, but Aquilina can’t think of anything more absurd. “If you’re affected by crime, you should be able to tell a judge. It’s the people’s court, it’s our laws, our community. It’s our Constitution,” she says. “If someone doesn’t like what I do, unseat me. It’s that important.”

What’s next? Well, there’s her family. The divorced mom of three had been on the court for a couple of years when she and her partner started talking about another baby. “Our relationship started to fall apart,” she says, “and I said, You know what? I don’t need him—sperm bank! So when I was 52, I did IVF, and I had twins.”

The twins are eight now; they live with Aquilina and her daughter Johanna, 18, in a two-family home shared with her parents. Her two oldest children are grown, but they still all gather for her German schinkenfleckerl and Maltese pastizzi (both recipes from her grandparents). She makes bracelets for her 14 pairs of cowboy boots, takes Bob Ross painting classes “to keep the blood pressure down,” and is finishing her next crime series, All Rise. In this latest opus, the main character’s motto is “Every day is a wedding hairspray day,” which happens to be Aquilina’s motto as well: She spritzes religiously, she says, so “I don’t have a thought or a care about what I look like—I simply focus on the case in front of me.”

And that is what’s next for now. Soon after the Nassar sentencing, she heard the case of a man who had sexually assaulted his 12-year-old daughter. In her victim’s statement Aquilina learned that when his wife kicked him out, he took the family dog. “It was his way of controlling her,” Aquilina says. “So I told him, ‘Sir, I’m ordering restitution: the dog.’” (She also sentenced him to prison time.) “That girl is never going to have her virginity again. But she’ll have her dog—her best friend—and her voice back. That case is just as important as a case with hundreds of women and all the media.”

She’s up for reelection in 2020 and hopes to serve until she retires at age 74. But she plans to live until 120. “That’s my number,” she says. “I keep telling God, I have work to do.”

Liz Brody is an investigative reporter in New York City. If you or a loved one has been a victim of sexual assault, get confidential counseling and information on how to report it from RAINN at 800-656-4673.