Joyce Maynard on Saying Goodbye to “This Is Us”

I sometimes speak of This Is Us, the beloved television series about to air its final episode, as my guilty pleasure. The truth is, I see no reason to feel guilty about loving this show, for all its occasional sentimentality and the tendency of its characters to hold forth now and then with Big Speeches About the Meaning of Life. For six seasons, this story, more than any other on television, has spoken to my experiences over the past four decades as a woman and as a mother.

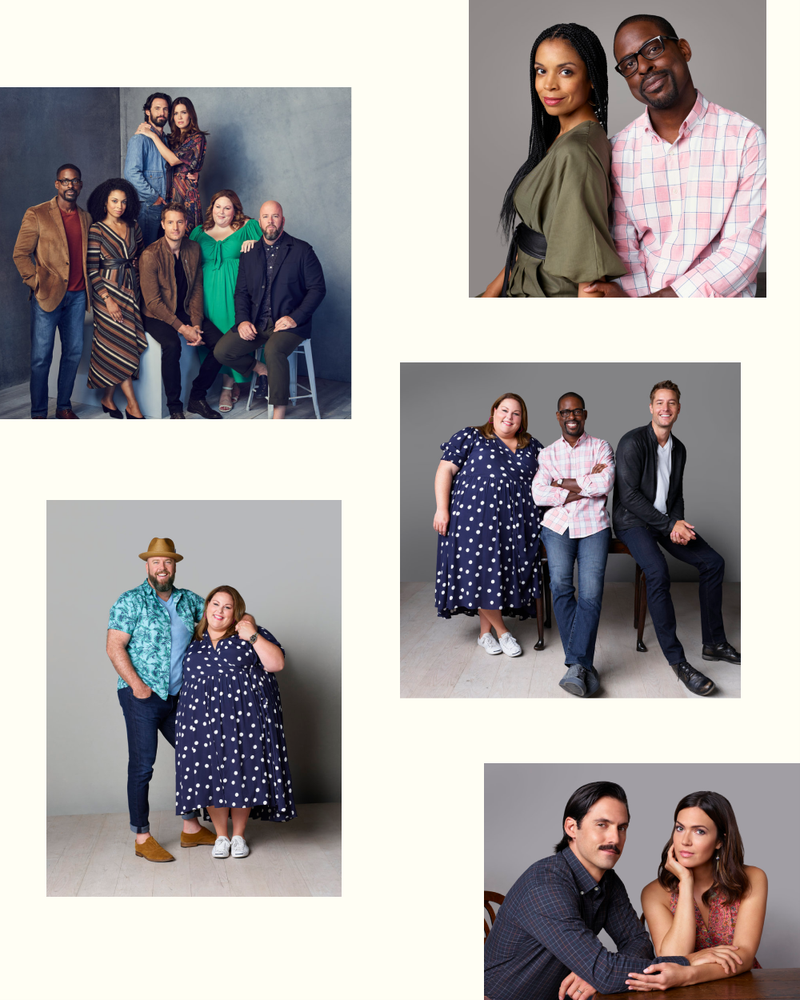

The actress who plays the central character, Mandy Moore, tweeted shortly before the airing of the second-to-last episode that after they watched it, people were probably going to have to stay home from work the next day. Maybe this was a slight exaggeration. But she wasn’t so far off. All across America, as the credits for that one rolled, viewers wept. I know I did.

For those who haven’t heard, This Is Us follows the story of a seemingly ordinary couple, Jack and Rebecca Pearson, living in Pittsburgh. One night in the summer of 1980, Rebecca gives birth to triplets. One of the babies dies. But on the very same night, someone leaves another newborn baby, who’s Black, on the steps of the hospital. Rebecca and Jack bring him home to be part of their family. And over the six seasons of the series that follow, some of us (me, for one, and a few million others) have followed those triplets and their parents and a whole constellation of other characters who came into their lives over the years.

In season two, Jack dies of smoke inhalation when their house burns down. A few years later, Rebecca marries Jack’s best friend, Miguel. One of the sons becomes a TV star. One becomes a civic leader and, eventually, a U.S. senator. The daughter is a music teacher for blind children. We follow marriages and divorces, illness and loss, eating disorders, PTSD, issues involving adoption, race, and substance abuse, and a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, which brought us to that second-to-last chapter in which Rebecca, in the final stages of the disease, lies on a bed in the house one of her sons had built for her as the family gathers to say goodbye.

There’s a reason why This Is Us speaks to me. The siblings in the show are roughly the age of my own three children. As their story gets underway, their mother, Rebecca, is roughly the age I was when my first child, my daughter Audrey, was born.

Nearly every stage I have watched this family go through has been one that I’ve lived through, too. (Like the Pearsons’ daughter, Kate, Audrey works with kids facing challenges. I even have a son who—like one of the three adult children on the show—is a successful television actor. Years ago, in fact—back when they were casting This Is Us—my son Wilson auditioned for the role of Kevin Pearson. Even now, when I watch the show, I imagine how it would be if it were Will up on the screen.)

Nearly every week for as long as I’ve been watching, moments in the life of the fictional television family have resonated with real-life memories: being so exhausted that I’d fall asleep in the middle of reading my children a chapter of Charlotte’s Web, dressing up for a rare dinner out my husband and I couldn’t afford, getting a haircut inspired by Princess Diana. Like Rebecca, I once sat at the edge of a pool during swim lessons—holding the one who was scared, cheering on the one who wasn’t. Years later, I saw my children head out into the world on their own, one by one, wishing I could protect them and knowing I couldn’t. In so many ways, the story of the Pearson family was my story, too.

Stark differences between our two families were equally obvious. Sometimes painfully so. Though Jack and Rebecca experienced disagreements and occasional tension over the years (moments we watched in flashbacks), their marriage never appeared less than solid and deeply loving. My own marriage ended—with no shortage of acrimony and a vast measure of grief—when our children were all under age 12.

One other part of the story followed over six years of watching This Is Us hit home: The Pearsons adopted a newborn infant whose birth parents were Black. As a single parent, in my mid-50s, I adopted two older Black children orphaned by AIDS. The Pearsons’ adopted son, Randall—though he struggles for a time over reconciling his place as a Black child in a white family—displays as deep a connection to his parents, his mother most of all.

My own adoption failed. For reasons I do not speak about to protect the privacy of the two children who briefly knew me as their mother, this is not a story I am free to tell. Though I made the choice I believed was the best for my adopted daughters, not a day has gone by over the past 11 years when I did not think of them.

I’m no Rebecca Pearson. Nobody knows better than I all the ways I have fallen short over the years.

Picture me just a few days ago, then, sitting in front of my laptop—which is where I follow the series—watching the episode in which Rebecca’s three adult children gather at their mother’s bedside as they say goodbye. Mandy Moore is made up to look like a woman around my age. One by one, in her final moments on Earth, each of the children tells their mother what she meant to them. Which is just about everything.

The scene led me to imagine my own death—taking place sometime in the next five, 10, 15, 20, or 30 years—and how my own three children will handle it.

For starters, as much as I believe my sons love me, I don’t anticipate that either one of them will build me a house to live out my final years. Where the fictional Pearson family gathers together every single Thanksgiving to honor all sorts of beautiful lifelong family traditions, I haven’t pulled off an all-family Thanksgiving since sometime in the ’90s.

There is this trap I fall into sometimes—most of us do, I think—of comparing myself to others around me who appear to have figured out how to make their way through life better than I have. Sometimes I go farther, and compare not just myself but our family to those of people around me—concluding that as much as we love each other, the idyllic moments I see in other people’s Facebook posts and holiday letters to friends suggest they’ve done a better job than I did at pulling off that most elusive goal: raising a happy family.

My children have scattered—two on one coast, one on the other. I see them as much as I can, but many months may go by between visits. My grandchildren know me mostly from FaceTime. This makes me sad. My children’s father and I—though we greet each other in a friendly way when we meet, as we did not in the earlier years following our divorce—have not achieved some life-altering reconciliation.

It is a source of incalculable joy that the younger of my adopted daughters is back in my life now. But not every story I’ve lived or those of most women I know has had a satisfying resolution.

On the second-to-last episode of This Is Us that aired last week, a Dream Rebecca, walking through a series of train cars in her imagination as she lies on her deathbed, reflects on the many characters we’ve met over the years of watching the series. Rebecca is unfailingly beautiful and kind, loving, understanding, wise. In all the episodes I watched over the years, she never once picks up a milk carton, as I did one time when my kids were young, and upends it over her head. She never throws an egg she was about to put into the pancake batter across the kitchen at one of her sons when he talks back to her. She never tears the family’s house apart in search of a lost Barbie shoe.

I published a novel recently, called Count the Ways, that explored territory uncannily similar to that in This Is Us, spanning more than four decades in the life of a family with three children. In that novel—a work of fiction inspired by personal experience, in which the fictional mother, bearing a certain resemblance to myself, occasionally visits a place I call Crazyland—the mother screws up regularly, in ways Rebecca Pearson never did.

As many heartbreaking events as transpired over those six seasons, at its core This Is Us is the story of a happy family. The stability of the children’s early days resonates throughout their lives. As much as the lives of three children in the show were shaped by the deep love and connection of their parents’ marriage, the lives of my own three well-loved children were affected by the rupture that took place in their father’s and mine.

My children’s father didn’t die, and it would be easy to conclude that a parent’s death is the greater trauma for a child than divorce. But divorce incurs a different kind of injury, also deep. Also enduring.

Mothers have a way of taking on responsibility for every single hard thing that happens in their children’s lives and blaming themselves. I have carried with me, always, regret that of all the things I wanted to give to my children and all the things I did to protect them when they were young, in this one crucial way I failed them. I couldn’t give them the experience of growing up with two happy, loving parents, raising them together side by side. I would have given almost anything to have been able to do that, same as I would have given a lot to have been the mother my adopted daughters needed.

Last week, sitting with my glass of wine—widowed, as Rebecca was, following a good and loving second marriage—I tuned in to that second-to-last episode and engaged once again in my habit of comparing my story to that of beautiful, serene, endlessly patient Rebecca Pearson, as portrayed by Mandy Moore. No big surprise, I fell short. Most of us would.

As I watched, the three television siblings—all in their 40s now, like my oldest two—had nothing but great things to say to Rebecca at her bedside, about the amazing job she’d done as their mother. The speeches my own children would make as I lay dying—in some imagined version of my own final chapter—might be more complicated. The same could be said of what my bedside farewells to my own parents would have been, had they taken place. If we were honest, there would have been some things to say to my parents about sorrow, loss, disappointment, and a wish that we could do some things over.

But here’s where I stand today, as a 68-year-old mother of three, still walking this Earth, fully or mostly in possession of all my faculties (though my right knee isn’t what it used to be). Maybe some of what I say about this will speak to some other imperfect mother, reading this, who felt the same sense of inadequacy, watching This Is Us over these past few episodes as the Pearson children prepared for the loss of their mother. I am probably not the only one who registered the thought, Oh God, what would my children say at such a moment about me?

We do the best we can. We all make large and sometimes damaging mistakes. At the end of the day, it is up to the next generation to decide what to do about those: Make our peace and move on, or allow ourselves to become embittered or crushed by them.

The consensus of the adult Pearson siblings on This Is Us appeared to be that Rebecca Pearson was probably the best mother in the history of the world. Her children will honor her memory forever, same as they do that of their father.

As for my children: I accept that the accolades at the time of my death may fall a little short of those delivered on the show. It’s enough that we love each other and forgive each other our failings and make our own good lives. As the daughter of two parents I deeply loved—both long dead—who made costly mistakes for which I forgave them long ago, here’s what I would like to receive from my own children whenever the day comes that they bid me farewell:

Love and forgiveness, simple as that.

Years ago, my daughter Audrey told me about four short sentences called the Ho’oponopono Prayer, which originated in Hawaii. “Speak these four sentences out loud to someone you care about—possibly a person with whom you’ve had issues—and things will change for the better,” she said. You can say them in any order with the same result, she told me.

My daughter wasn’t wrong. The sentences of the prayer go like this:

I love you. I’m sorry. Thank you. Please forgive me. More than once over the years, when I have spoken those phrases out loud to somebody, something shifts.

I don’t need to be some icon of Perfect Motherhood in my children’s eyes. I’ll take human. More valuable even than the lessons our children may learn from our accomplishments and successes are those they take from our failures and shortcomings, particularly when we admit to them.

That’s where compassion comes from. That’s how they may learn, perhaps, how to do better themselves.

A television series ends, eventually. A family goes on.

New York Times bestselling author Joyce Maynard’s most recent book is Count the Ways. Out in paperback this summer, her story, like This Is Us, follows the lives of a couple and their three children over 40 years, from the late ’70s to the early 2000s.

You Might Also Like