How Joshua Tree Became an Artists' Haven — and One of California's Coolest Destinations

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The area around California’s Joshua Tree National Park has long exerted a gravitational pull on artists, seekers, and freewheelers. But this secret desert hideout isn’t so secret anymore.

Yasara Gunawardena

Joshua Tree National Park is named for its distinctive trees, which are endemic to the Mojave Desert.Time, in the high desert, moves more slowly. It certainly feels that way in Joshua Tree. My wife, Rachel, and I drive out to the region at least once a year, to sink into that change of speed. As a writer, I find the area both intimidating and beguiling — a heady, inspiring combination.

Others have felt the headiness, too. Across generations, Joshua Tree has drawn waves of film people, music people, fine artists. Ann Magnuson, Jim Morrison, Ed Ruscha. It’s not for everyone, but it is for some—those who choose to stay and build and nurture in a setting that can feel isolating with all that empty space, all those cactus shadows stretching across the sand.

Lately, though, the desert is becoming less empty. In 2021, Joshua Tree National Park welcomed more than 3 million sightseers, a 50 percent increase from 2015. In the town of Yucca Valley, not far from the park gates, tax revenues from hotels and vacation rentals went up sixfold in five years. Residents described the influx to me as a mix of real estate developers, big-city exiles, and people buying second homes. House prices have exploded. People are worried about overtourism. A year ago, I stayed with an actor friend in the area who said the last property on his block had just been converted — he now lived on a street of Airbnbs.

Yasara Gunawardena

From left: No Contest, by the late sculptor Noah Purifoy, at the Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum; accommodations at AutoCamp Joshua Tree include 47 refurbished Airstreams (A/C included).Hearing that, I got curious about what that meant for the artists who did so much to make the place compelling — both for other artists and for commercial interests, too. What had the desert offered them in the first place, and what had changed?

Joshua Tree refers to the national park, an expanse the size of Rhode Island where the Mojave and Colorado deserts converge, but also to an actual town — as well as a string of small communities draped like a necklace across the park’s northern rim. About a two-hour drive from Los Angeles, the region runs along Highway 62 for 30 or so miles. You know you’re getting close when the pavement starts to shimmer from the heat and wind turbines dot the view like enormous white palms.

I got curious about what that meant for the artists who did so much to make the place compelling— both for other artists and for commercial interests, too. What had the desert offered them in the first place, and what had changed?

On our most recent trip, in late June, the daytime high was expected to break 100, so our first thought as we drove into town was a drink. A friend recommended the Tiny Pony Tavern, a new place in Yucca Valley popular with the artist and queer communities — and pretty much everybody else. That afternoon, patrons included a young family, several construction workers, and a woman in rock-climbing gear (the park is a big climbing destination). Cocktails were excellent; same for a bowl of duck-confit nachos. It felt like all of us were getting away with something, hiding from the sun in the dark.

An hour later, we pulled in to AutoCamp, which is situated a short drive from the park’s west entrance. There were gleaming silver trailers everywhere we looked. The company also offers Airstream glamping in locations like Yosemite and Cape Cod; at the Joshua Tree outpost, which opened just a few months before our stay, guests can sample the wilderness across the road or have a cocktail by the pool while a local musician plays. “After the past couple years, people want to get out in the open,” Chris Rodriguez, one of the managers, told me. “They want to have space.”

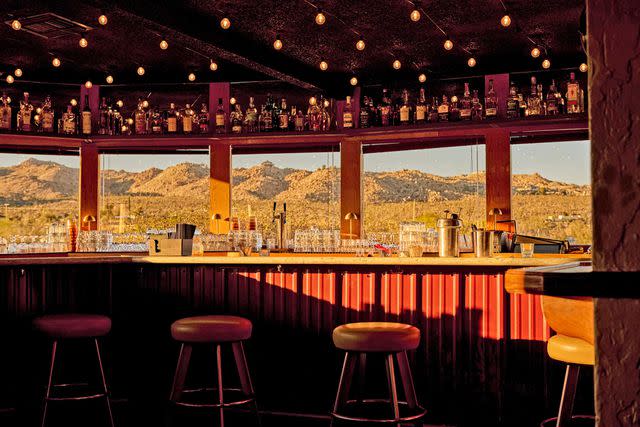

Yasara Gunawardena

The edge of Joshua Tree National Park, as seen from the bar at the Copper Room.Darkness fell quickly. Outside our door was a firepit and a pair of Adirondack chairs, out of view from the other trailers. I ordered a barbecue kit from reception: New York strip, potato salad, mac and cheese. We grilled the steaks over a fire and opened a bottle of wine. Many firepits flickered—families cooking, couples laughing. The vibe was camping-lite, great for a group of friends on a weekend break from L.A., but not really my thing. Then the real showpiece arrived: thousands of stars began to illuminate the sky. Joshua Tree is known for stargazing; the total canopy was mesmerizing, and my neck started to ache.

“I’ve got an idea,” Rachel said. She grabbed a pair of bathrobes and spread them out on the ground like blankets so we could lay in the sand and watch. When we got up an hour later, it felt like just minutes had gone by.

The desert often draws searchers, nomadic types, people looking to get lost for a bit in all of the immensity — or, conversely, to find themselves. The next morning, it was a 20-minute drive north from AutoCamp to Landers, an unincorporated community with one of the area’s biggest draws: the Integratron, a classic seeker’s shrine.

Yasara Gunawardena

From left: Sculptor Sarah Vanderlip’s CA.Truckheads on the grounds of A-Z West; at A-Z West, the former home of artist and Joshua Tree icon Andrea Zittel is available to rent.Constructed in the 1950s by self-styled “UFOlogist” George Van Tassel, the design, he claimed, was relayed to him by extraterrestrial beings, along with instructions for amplifying Earth’s magnetic field. What we discovered was an extraordinary acoustical experience—an hour-long sound bath inside the building’s gigantic wooden dome. “If it feels like you just crawled inside a wooden instrument,” said our meditation guide, “it’s because you did.”

For nearly an hour, the guide played a dozen-plus singing bowls while a group of us, seemingly all out-of-towners, lay on mats and absorbed the sound. At times it was incredibly loud, oscillating in my head. Other points, it was so quiet, I could hear someone snoring. “I can’t remember the last time my body felt this relaxed,” Rachel said.

We stopped afterward at the Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Sculpture. Purifoy, a Black sculptor from Los Angeles, died in Joshua Tree in 2004, having moved his art practice there in the 1980s. For the last 15 years of his life, he dedicated himself to constructing a 10-acre sculpture park in the sand. We walked around an array of pieces exemplifying Purifoy’s distinctive style, described by the curators of a 2015 retrospective as “junk Dada.” There was a tower of toilets and a train assembled from old kegs. There was a cabin built from wood scraps, large enough to live inside. I felt like I was wandering through a community abandoned long ago, though deeply loved when it was made.

Yasara Gunawardena

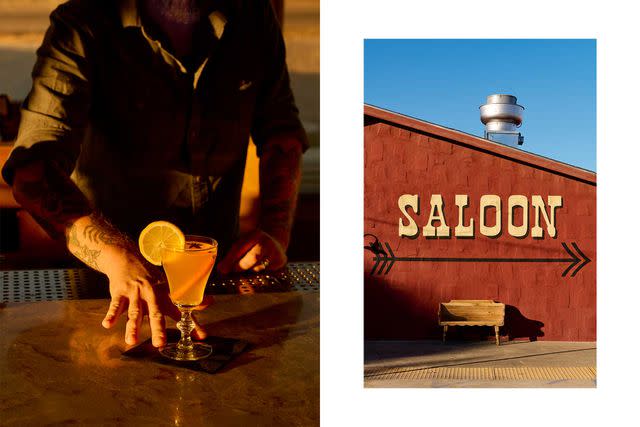

From left: A hot toddy for all seasons at the Copper Room, established in 1957; Pioneertown’s Red Dog Saloon is a favorite for tacos and tequila.We grabbed lunch at the Joshua Tree Saloon, a weathered haunt for burgers and beer. It’s the kind of place where it wasn’t a surprise to hear the Grateful Dead when we walked inside. At the same time, it was slammed—hardly a relic. Signs of the area’s older guard, I thought, were perhaps tricky to find in the current melee, but traces existed. And now a newer wave was making its way.

In the 1970s, the country singer Gram Parsons rolled into Joshua Tree in an Aston Martin to drink margaritas and watch the sunset. Donovan, the folk musician, later raised his family there. Alma Allen, before departing for Mexico, made sculptures inside a Quonset hut in the desert by operating a massive robot previously used to build cars. Others currently working in Joshua Tree include the assemblage artist Bobby Furst and the architect Linda Taalman.

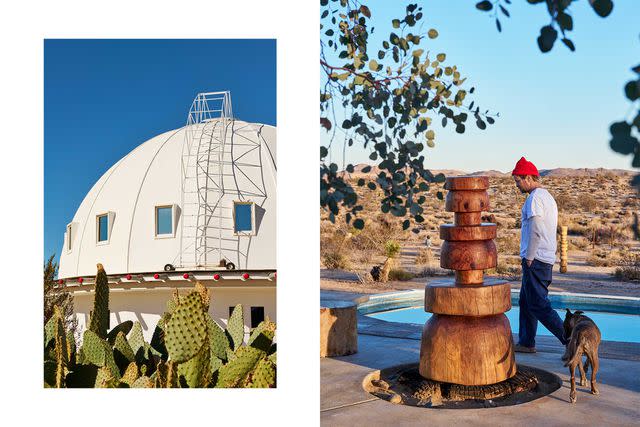

Sculptor Dan John Anderson, originally from eastern Washington, moved to the high desert in 2012. He invited Rachel and me to his Yucca Valley studio, which was brimming with saws and hand tools. Anderson is known for large wooden sculptures, some resembling modern chess pieces, others abstract stools. For him, the desert provides a harsh beauty and an enticing sense of limitlessness. “The nature here, it’s not a Disney show,” he told me. “There’s a psychological space, a general freedom, that gives me the room to explore.”

Yasara Gunawardena

From left: Lunch at La Copine, in Yucca Valley, includes green beans with tahini, gem lettuce salad, artichoke toast, and a cake of Pacific rockfish; guests at the Tiny Pony Tavern before things get busy.I was introduced to Anderson through one of his close friends, the painter Lily Stockman. Stockman bought a homestead cabin in Joshua Tree in 2013 and has lived there part-time ever since. Both she and Anderson are very aware of the precariousness of the place as it becomes more of a tourist destination. “To spend time in these mountains is to experience visible, condensed geological time,” Stockman told me by email. “I keep coming back to a line from the California poet Kay Ryan: a larger amount is no longer a larger amount.”

I’d felt something similar during previous camping trips in the area. To absorb the grandeur of the landscape, to feel its age, can expand one’s sense of scale.

More Trip Ideas: 9 Best National Parks In California

Anderson suggested we continue our conversation over tacos at Red Dog Saloon, a honky-tonk reopened in 2020 in nearby Pioneertown. If it looks like something out of an old western, that’s because it’s how the place got its start. Pioneertown opened in 1946 when a group of Hollywood actors, musicians, and producers, including Roy Rogers, built their own living motion-picture set. It was mocked up like a Wild West village, one where cast and crew could spend the night.=

Pioneertown has since been updated. Pappy & Harriet’s Pioneertown Palace, the venerable club-slash-barbecue joint, today books big acts like Belle & Sebastian. In May, just before my visit, Pioneertown had hosted an international film festival. And the tacos at Red Dog were as good as you’d find anywhere in southern California: shredded beef brisket, cider-braised pork carnitas, mushroom asada with tomatillo salsa.

Anderson voiced his concerns for the region. Mainly that young artists were struggling to find and afford adequate space to live and work. The desert’s inspiration still felt limitless—Anderson said he liked to explore the mountains on his dirt bike—but only if people could support themselves.

I asked Mike French, who bought the Pioneertown Motel with his brother in 2014, to describe Joshua Tree’s persistent appeal. “At the end of the day it’s a feeling,” he said. “In the desert, you’re in it. You’re so in it. There’s something grounding about that.”

Of course, the success of the French brothers and others represents a double-edged sword. In their case, they’d hired local craftspeople to help revitalize local landmarks—make them fashionable, freshly desirable—which in turn created local jobs. But what good is a waitressing gig to a Cal Arts grad if she has nowhere to store her canvases?

Yasara Gunawardena

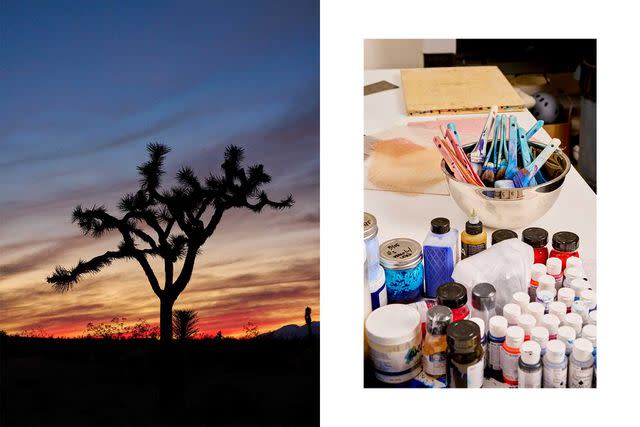

From left: Sunset at California’s Joshua Tree National Park; inks and other printmaking supplies in the studio of artist Kyle Simon.

On Anderson's recommendation I reached out to Kyle Simon, another high desert artist. Simon is a Master Printer, formerly of Pace Prints, the New York City fine-art publisher. He agreed to show us where he and his wife, Sarah, were homesteading in the mountains. He also agreed to pick us up, because the drive required a vehicle better equipped for off-roading than ours.

Prior to his move to Joshua Tree, Simon collaborated with some of the world’s biggest artists to create limited-edition prints. But, he says, “I was ready for a big change.” For him, that involved building himself perhaps the world’s first off-the-grid print studio, Farrington Press, way out in the Mojave Desert. Now the artists come to him.

I’d felt something similar during previous camping trips in the area. To absorb the grandeur of the landscape, to feel its age, can expand one’s sense of scale.

Simon asked me and Rachel to keep his site’s location private. The drive was a long one, though the majesty of the landscape made time pass fast: little streambeds, large bluffs, groves of huge Joshua trees. Simon’s home and studio are located on several acres overlooking a long valley. “It’s such a lunar landscape,” he said. “It’s unlike anything I’ve ever really been in.”

The studio, though, was more sophisticated than we had expected: multiple tools and presses, deep archives of materials from past collaborations. Simon showed us prints that the artist Ryan Schneider had made with chainsaw-cut woodblocks. For a project with Lily Stockman, he’d constructed a box for aquatinting, a technique used most famously by Francisco Goya. All of this with miles of scrub and boulders and endless sky right outside the door.

What united Simon and Anderson and Stockman and the rest seemed to be a sense of grit, a rugged independence. Equally important was the pleasure of spending time with people who approached art and life the same way.

Yasara Gunawardena

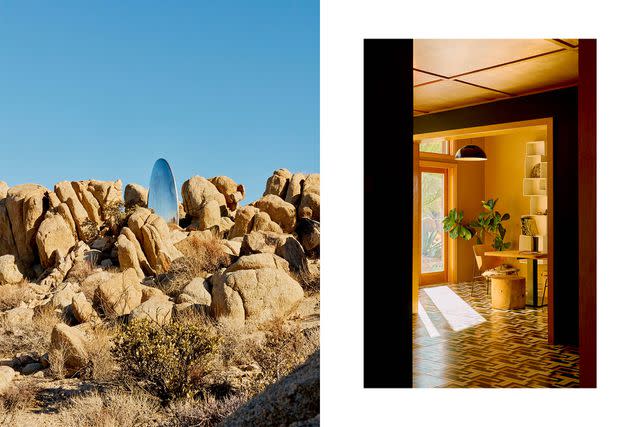

From left: The Integratron, created as a sort of alien-medicine laboratory by a local “UFOlogist,” is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places; Joshua Tree–based sculptor Dan John Anderson with one of his signature wood pieces and his dog, Rookie.Perhaps the person most strongly associated with the latest wave of contemporary art in Joshua Tree is Andrea Zittel. Zittel moved her studio from New York City to the desert in 2000. She has become known for an eclectic oeuvre that includes paintings, experimental shelters, and furniture. For our final night, Rachel and I rented a guest cabin at A-Z West, a sort of compound meets artist community meets artwork Zittel created on 80-plus acres of desert holly and creosote bush lodged right up against the national park.

Zittel’s role in the community has been enormous, people told me. Her impact was both aesthetic and social: a globally recognized artist encouraging so many young people to live and work in Joshua Tree. “Andrea’s influence here is incredible,” Anderson said. “Even on the Airbnb-ers, and they don’t realize it.”

Our home for the night was a one-bedroom house with big views. Formerly a homestead cabin, it now features prototypes of furniture and many books and paintings, not to mention a minimalist outdoor shower that was fantastic after a long day in the heat. The property is no longer Zittel’s home; instead, she rents out the cabins, putting the proceeds toward High Desert Test Sites, a nonprofit she cofounded to support local artists and events.

It struck me that the desert was an archive of geological moments, but also human ones.

Nearly everyone we met in Joshua Tree suggested we go to the Palms Restaurant in Wonder Valley, about 30 miles east, for cocktails, so that’s where we spent our evening. Across the street was an enormous sculpture by Paloma Varga Weisz, part of a temporary exhibition put on by HDTS; another, by Jack Pierson, was around the corner. But for all the art, the Palms basically felt like a dive bar at the end of the world. Clientele were desert rats, young and old, some long-haired and scruffy, some clean-shaven with cowboy hats. A man next to us ordered “a couple of martinis” and a glass of milk. (His martinis, which contained maybe six shots of gin each, were served in margarita glasses.) Another guy asked for a Diet Pepsi and a Ding Dong; the bar had both.

As the sky blackened, we made one final stop. We’d been told by the staff at A-Z West that, if we were up for it, we might be able to catch a concert in the hinterlands that night.

We drove north for several miles on sand. There weren’t any lights, no structures, just rutted roads and a bright moon. I started to worry about getting a flat tire. Rachel said: “What’s the worst that happens? We hike back.”

Then, suddenly, there were cars and lights. An old firehouse had been repurposed for a concert, part of a series of events organized by HDTS that people mostly learn about through word of mouth (or Instagram). That night, two local acts, Earl Vallie and Earth Girl Helen Brown, were performing before heading out on tour. We ran into Anderson, the sculptor, and other folks we’d met that week, their faces abruptly appearing out of the darkness to drink and dance.

More Trip Ideas: These 10 Hidden Gems Are California's Best-kept Secrets

The Joshua Tree boom has enriched many residents — and outsiders. At the same time, many of the ripple effects of such a boom (gentrification, aesthetic homogeneity) are problematic, and the area’s rareness, its oddness, felt to me endangered somehow. And yet, all booms go bust. It struck me that the desert was an archive of geological moments, but also human ones. Because what I heard from people was that the region’s wide open spaces, whether booming or busting, actually foster intense, close community. As if its immensity, ironically, enables a person to see things more sharply — the artist’s job description, now and forever.

High Desert Road Map

Where to Stay

A-Z West: Artist Andrea Zittel’s 80-plusacre “testing ground” includes a two-bedroom house and a one-bedroom guest cabin, both available for overnight stays, and hosts regular public tours.

AutoCamp Joshua Tree: This chic trailer resort has 47 Airstreams outfitted with kitchenettes and walk-in showers, plus a handful of modern bungalows. The property also has a general store (with cooking kits and premade meals) and a swimming pool.

The Bungalows by Homestead Modern: Fourteen renovated Midcentury Modern suites at the Joshua Tree Retreat Center, a historic campus with many buildings designed by Lloyd Wright, son of Frank Lloyd Wright.

Pioneertown Motel: Actors and crew filming in Pioneertown, a purpose-built Old West movie set, would spend the night here during shoots. Sibling owners Matt and Mike French completed a full renovation of the 19-room inn in 2016.

Where to Eat and Drink

Copper Room: Once a lounge for the Yucca Valley Airport — frequented by rock stars and Rat Pack types — the restaurant reopened in summer 2022. Order the Gram-arita: a margarita the way Gram Parsons liked it, with a half salted rim.

La Copine: Chef Nikki Hill and her wife, Claire Wadsworth, transformed a run-down diner into this seasonally focused restaurant, which has a loyal following despite its limited hours: 11 to 4, Thursday to Sunday.

Joshua Tree Saloon: Burgers, beers, and live music in an old-timey wooden watering hole.

The Palms: The whole Joshua Tree cast of characters comes together at this venerable dive and music venue in Wonder Valley.

Pappy & Harriet’s Pioneertown Palace: Formerly a “cantina” for Hollywood westerns, the building has been a real-life restaurant, bar, and music venue since 1972.

Red Dog Saloon: This movie-set saloon in Pioneertown is now a destination for tacos and agave spirits.

The Tiny Pony Tavern: This queer-friendly favorite serves tropical drinks and creative bar food: wild-boar sloppy joes, yuca fries with queso, and lemon-habanero cheesecake.

What to Do

The Integratron: In the 1950s, George Van Tassel claimed to have access to extraterrestrial technology. These days, the structure he built is a venue for guided sound baths.

Joshua Tree National Park: Named for its Seussian trees, the 1,240-square-mile park has nine camping areas and more than 30 hiking trails at the intersection of the Mojave and Colorado deserts.

Noah Purifoy Outdoor Desert Art Museum of Assemblage Sculpture: The groundbreaking sculptor filled his 10-acre propertywith dozens of his characteristic works, which were made with found materials.

The Station: A converted 1949 service station is stocked with desert souvenirs like serapes, vintage curios, and even potted cacti.

Wine & Rock Shop: Natural wine and New Age crystals. Need we say more?

A version of this story first appeared in the April 2023 issue of Travel + Leisure under the headline "Time and Space."

For more Travel & Leisure news, make sure to sign up for our newsletter!

Read the original article on Travel & Leisure.