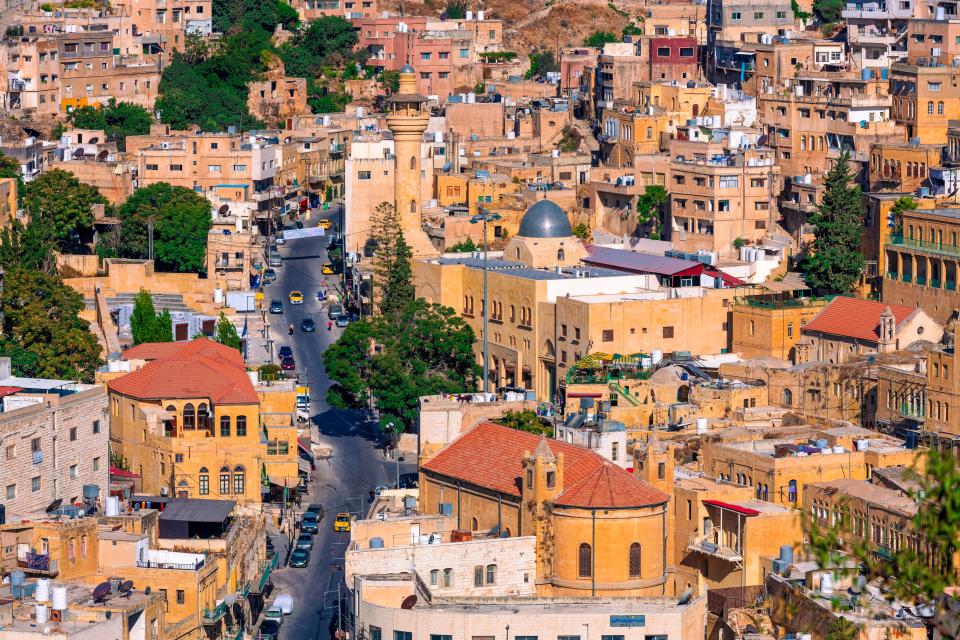

In Jordan, a Community Disrupted Awaits Travel’s Return

Wirestock

Trying my best not to make a mess, I devoured the chocolate-drizzled, walnut-topped qatayef and instantly felt better about the wet, wintery day. In Jordan and throughout the Middle East, these palm-sized semolina pancakes are typically only popular during the holy month of Ramadan—As-Salt, a city on three hills about an hour north of the Jordanian capital of Amman, is “the only place where one can find qatayef year-round,” my As-Salti guide Sewar Alfauori explained between bites.

Minutes earlier, a downpour had drenched the city in buckets of water that now cascaded down the steep limestone streets. In a futile effort to escape the rain, we had stopped by the pastry stand at the deserted Al Hammam Street, a pedestrian-only thoroughfare that normally attracts travelers to its spice and textile shops in As-Salt’s UNESCO World Heritage city center.

Travel to Jordan, which shares a western border with Israel and the occupied West Bank Palestinian territories, has reduced dramatically in the last six months. According to the Jordanian Ministry of Tourism and Antiquities, visitations dropped by 80-90% in some places due to concerns for safety in the region following the months-long war in Gaza in response to the October 7 Hamas attack. The impact of the neighboring crisis has been devastating for the country where tourism serves as the largest export sector and second largest employer.

As-Salt © Fadi Amireh.jpg

Although As-Salt is not as well known among travelers today as the ancient Nabataean city of Petra or the Mars-red Wadi Rum desert, the city played a vital role in the region’s development. Occupied since the Iron Age, it blossomed in the 19th and early 20th centuries, during the late Ottoman period. As-Salt was the crossing point of pilgrims on the way to Mecca and traders headed for Europe, Asia, or Africa. This strategic location helped turn the small village—known as ‘Saltus’ in Roman times—into a major commerce hub. Merchants from Syria, Lebanon, and Palestine settled in As-Salt to trade goods like livestock, grains, textiles, and plant dyes. By way of Damascus, As-Salti wool reached as far as the European and American markets; from the ports of Haifa, crops like wheat and raisins spread across the Mediterranean.

Where trade flourished, people gathered. Soon, As-Salt attracted skilled craftsmen, architects, and stone masons who built its characteristic golden-colored limestone houses with public gathering spaces, internal courtyards, domed roofs, and tall, arched windows. At the crossroads of cultures, ideas, and groups of people—Bedouin sheiks, Ottoman officials, Christian missionaries, and Levantine traders—As-Salt became famous for a practice known locally as takaful al-ijtimai—a unique blend of Bedouin hospitality and tolerance of diverse ideas, religions, and cultural traditions. It manifested in the creation of multiple madhafa guesthouses and entire neighborhoods where people of all backgrounds lived side by side.

As Alfauori conveyed these facts to me with the enthusiasm only professional guides possess, she turned somber. “For most of last year, I had two or three daily tours around the city,” she said, adding: “You are only my third tour since the beginning of this year.”

I’ve been traveling to Jordan several times a year for nearly a decade. After October 7th I wanted to see for myself how local communities are coping since the Israeli military campaign on Gaza began. This February, I visited Amman to catch up with Yasar Malhas, a Jordanian tour operator who runs Pan East Tours. “We have zero work,” she said, “but we are hanging on.”

Back in As-Salt, the rain eventually stopped, revealing a lush green tapestry of landscapes like olive groves and Mediterranean forests, a calling card of northern Jordan. From the historic city, I moved further north to Jerash, one of the Roman Empire’s most important outposts at the dawn of the first millennium. In Jerash, I tried my hand at baking zalabia, a fluffy bread made with sesame seeds, yogurt, and olive oil. This experience is one of many provided by Dar Ne’meh, a community tourism project employing women, orphaned girls, and refugees in five hubs across Jordan.

Dar Ne’meh has helped nearly 3,000 women create a sustaining income for themselves and their families in the last five years, according to the Princess Taghrid Institute, which oversees the project. “When you support one woman, you’re supporting five to six people in the community,” said PTI’s general director Dr. Aghadeer Jweihan while we shared a meal of chaa’cheel, a local specialty in which dumplings stuffed with a native wild plant called loof (Arum Palaestinum) are slowly cooked in jameed, a fermented dry yogurt.

Traveling across Jordan from north to south takes just eight hours. Yet, in this small area, people of different faiths–Muslims, Druze, Christians of Catholic, Orthodox Greek, Syrian, and Coptic denominations–have coexisted for centuries. Heading south from Jerash, I soon arrived in Madaba, an Arab Christian town dating back to the times of the Crusaders where the world’s oldest map of the Holy Land, a mosaic treasure, lies for all to see on the floor of a Byzantine church.

A fresh arrival to Madaba’s dining scene, Carob House is a farm-to-table restaurant and community kitchen supplied by a zero-waste farm just outside of town. Jordan’s ecotourism veteran Rakan Mehyar founded Carob House to grow clean, nutritious food sustainably using time-tested practices like crop diversity and composting. Community is at the core of this operation: Carob House supports a network of small farmers, mostly women, in nearby villages who produce artisanal-quality products such as bottled carob molasses I happily acquired during my visit.

In the Carob House restaurant, led by chef Sarah Yassine, Mehyar and his team are resurrecting food traditions indigenous to this region. “This is where humanity’s agriculture originated, which means our food is thousands of years old,” said Mehyar. “Our menu is based on heritage recipes, but we leave room for contemporary creativity.”

At the communal dining table, I tasted dishes hard to find elsewhere on Jordan’s touristic trail: hearty soup made with native plants like mallow and gundelia (a type of thistle), pumpkin kubbeh inspired by lent, during which Madaba’s Christian residents make a vegetarian version of this meat dish, and ice cream made with carob foraged nearby.

“We want to connect travelers and local communities with farmers, celebrating the food that farmers grow,” said Mehyar. “Unless we create abundance in the soil, reimagine the way we grow our food, and share the goodness with others, I see a gloomy world.”

***

Deposit of salt and gypsum by the cliff in Dead Sea, Jordan

Just 20 miles south of Madaba, a nondescript hill called Mukawir overlooks the Dead Sea. At the top of this quiet hill, a bird’s-eye view of Jerusalem forms a backdrop to the ruins of Machaerus, a fortified castle built by biblical despot Herod. Although calamities befell Machaerus in the past—this site is considered to be where John the Baptist met his beheading fate—today it is entirely peaceful. I felt completely safe on this quiet shore—and throughout my entire visit—but it was not devoid of heart-wrenching emotion as I recognized and mourned the massive loss of life that took place so close to where I stood. Headlines about the Middle East often paint the region with a broad, often negative stroke. I’m glad that as a traveler, I’ve had the opportunity to go, see, and experience firsthand the overwhelming hospitality of Jordan’s many cultures.

I stopped at Mukawir for breakfast with the women of the Bani Hamida Weaving Project. When tourism numbers are high, Bani Hamida supports over 1,800 women from 14 remote villages in the area who craft exquisite wool carpets and upholstery in traditional and modern designs. In times like this, the women are managing to stay busy and put their products on the global stage through a partnership with IKEA, which now carries some of their designs in stores worldwide.

“We are able to help our households, improve our living conditions, and put our children through school,” explained Amal Kaida, one of the women greeting us over the breakfast spread of soft balls of labneh, mounds of zaatar, olives, and pickled eggplant called makdous. “But I want to know where you’re from,” she added, filling my cup with the third round of sage tea.

Back in As-Salt, I thought about Jordan’s role as the region's shelter from conflict. Throughout history, people have come to this country to escape violence and war. From Circassians fleeing the persecution of the Russian Empire in the 18th century, to survivors of the Armenian Genocide during World War I, to Palestinians who have built a new life in Jordan since being removed from their lands in the 1948 Nakba, entire communities have found a haven in Jordan. That is what makes it the vibrant, eclectic mix of cultures it is today.

A common trait now underpins these diverse communities: a steadfast warmth and generosity. Once I first tasted the flavor of As-Salt’s takaful al-ijtimai, I found it impossible to not come back for more.

Originally Appeared on Condé Nast Traveler