To Join One of Running’s Most Elite Clubs, All He Had to Do Was Run 26.2 Miles on a Glacier

White mountains roll into the horizon. Freezing temperatures and subzero wind chills harden the air. Here, in this nearly untouched land, the sun shines, uninterrupted, for six months over blankets of snow so fine it has its own name: spindrift. For 62 runners from 21 nations, the Union Glacier in Antarctica is home for a brief period as they attempt the 16th annual Antarctic Ice Marathon. They are racing on snow and ice to qualify for one of the most elite groups on earth: the 7 Continents Marathon Club.

The plane approached the blue-ice runway—made of glacial ice compacted over the centuries and the safest surface to land a plane on in Antarctica—after a five-hour flight from Punta Arenas, Chile, the southernmost port in the Americas. But Jeff Tan, a 41-year-old adventure runner, hadn’t realized they’d arrived. It was hard to tell where the whiteness of the clouds ended and the whiteness of the snow began. Only when an outline of darkness from what seemed to be the Ellsworth Mountains emerged did he realize that what he was descending into was snow—pure and unadulterated.

This is it, he thought. We’re here.

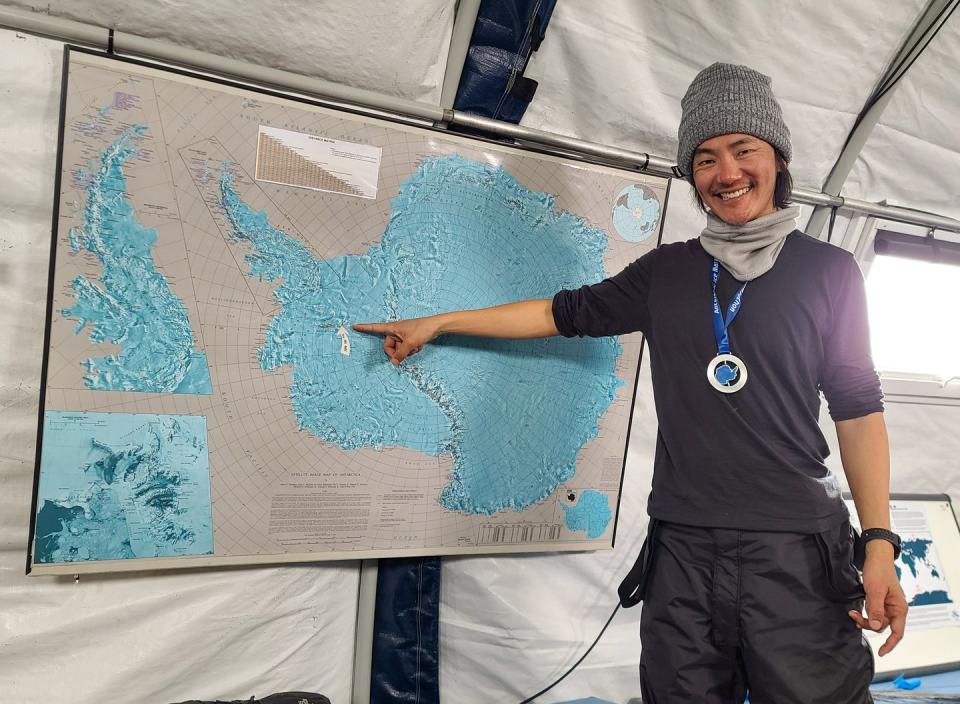

As he took in the landscape, Tan kept thinking, I’m going to achieve my dream. But he was still nervous that something might stop it. He had already come close to having that dream dashed: Just before his plane took off in Chile, he was deported back to the United States due to a paperwork mishap. Storms delayed the other runners, who had to stay an extra five days in Chile before departing. Tan made it back, but by the time they landed on the blue ice, they had just under 34 hours to exit the plane, set up tents, run 26.2 miles in subzero temperatures, take a few photos, pack up, and leave. At a prerace meeting, Richard Donovan, the race director, told the runners that their time on the glacier would split their lives in two: before Antarctica and after Antarctica.

Tan was determined to get through this race. “If I break a leg down there, I will drag my bloodied leg around each lap,” he joked. After a short orientation in a solar-heated tent on that December day, he and 61 other runners were off. It was five degrees Fahrenheit.

Today, Tan appears to have been built for adventure running. He is six foot one and thin, with tattoos on his arms and back. As a child he was lanky, one of the tallest kids in his class. Born in Sydney to Singaporean immigrants, Tan grew up in a predominantly white working-class area. For much of his childhood in the 1980s and ’90s, kids tortured him with racist taunts and obscenities. “It was a daily occurrence,” he said. Tan felt deeply alone. “Children are tribalists. They would learn horrible slang from their parents and call me names,” he told me when we met at a café in Los Angeles, where we both live. “If you don’t look like them, they will reject you. And I knew I was different.”

The thing that really mattered to the people around him, he said, was sports. “And I had no sporting ability, or at least I didn’t think I did.” Tan excelled in school and loved classical music. He took to the solitary nature of the piano and practiced for two hours every day.

Tan was raised in an evangelical Christian home. “The type of religion I grew up in was like the thought police from George Orwell’s 1984,” he said. He felt a requisite blind faith to never question anything, a complete indoctrination into fundamentalist religion. As he got older, that dogma didn’t sit well with him. “I started having creeping doubts,” he says. As his mastery of the piano developed, people would tell him it was not a product of hard work, but rather a gift from God. “If you tell yourself every day you are worthless without God, or you are a disgusting sinner and need forgiveness and redemption,” he says, “then it takes away personal agency.” By the age of 17, his faith had dissolved.

Around the same time, he was working toward the Licentiate in Music of Australia, one of the most prestigious music degrees in the country. But still he wondered if, without religion, he’d lose his talent. “Now that I’ve turned away from God,” he thought at the time, “just like when Samson chopped off his hair in the Bible, I thought that would happen to me.” He saw it as a test: Could he achieve the degree on his own, without God and his faith community? “I doubled down and I practiced harder, and I got the qualification. That was final validation that I could do anything I personally wanted to do.” By age 18, he had won a contest that led to him performing Chopin’s “Fantaisie Impromptu” at the Sydney Opera House for an audience of 2,000.

After high school, Tan officially left the church, joined a rock band in Sydney, and enrolled in the University of New South Wales to study engineering. In 2005, a year after graduating, he moved to London and took an apartment across from Clapham Common, a park on the south side of the city. His roommate, Adam Kennedy, was a casual runner, and eventually Tan began to join him occasionally for runs of one to three miles.

“Jeff wasn’t an athletic, sporty guy,” Kennedy says. “He looked a bit ridiculous the first couple of times.” Tan would head out in Vans and board shorts, until he bought his very first pair of running shoes: the Nike Lunarglide 4, in blue. “I was really proud of them,” he says.

Tan was settling into life in London. Running began to fill his free time. When he turned 27, his beloved older sister, Jo, became sick with cervical cancer. It had metastasized quickly and she had little time left. He flew home in October 2008 to be with her, and the following month she died at the age of 33. It was “the rawest pain any person can go through,” he says. “I definitely wouldn’t be the person I am today if it wasn’t for her. She was such a strong, positive influence and an example of what confidence could look like.” Tan stayed in Australia, mourning his loss and piecing together a new life. He enrolled in business school in Melbourne. And as he dealt with the grief and tried to figure out what direction he wanted his life to take, Tan turned to a familiar, solitary activity: He ran.

In 2013, a friend from business school asked Tan to run the Melbourne Marathon with him. It felt more like a dare than an invitation. “At that point, I’d only ever run three miles around Clapham Common in London.” But he couldn’t stop thinking about the marathon. “If my mate who is a runner thinks I can do it, then why would he lie to me? I can do it. All you have to do is run.” Tan signed up, went on a training run with his friend—and then the friend dropped out. So Tan trained on his own. He’d already committed to the race, he reasoned, and it was that drive—the one that fueled his pursuit of musical expertise at an early age—that made him want to see the goal to the end. Tan crossed the finish line in the Melbourne Cricket Grounds with a time of 3:57 and a profound feeling of pride.

Soon after, as Tan was heading to a vacation in Medellín, Colombia, he found out that the city had a marathon coming up. He adjusted his travel plans so he could participate. Once he finished, he had an idea: Why not run a run a marathon on every continent? Had it ever been done? A quick Google search turned up the 7 Continents Marathon Club, and from that point on, Tan mapped out the next five years of his life: five marathons each year, with the goal of ending in Antarctica. So by the time he finally set foot on the Union Glacier, he had run marathons in New York City, Copenhagen, Tokyo, and South Africa.

The Antarctic Ice Marathon is four laps of roughly 10 kilometers each, with an artificial Christmas tree marking the halfway point. Each lap feels different. Because Antarctica is a desert, it is extremely dry in addition to being extremely cold. The snow changes every 50 meters or so—deep in some places, more compact in others. Tan hadn’t expected the snow to feel like running on sand. He worried he might hurt his ankle. “It’s a sensory vacuum,” he told me. As soon as you separate from the pack, when it’s not windy, it’s pure silence. All you hear is your own breath and the crunch of the ice.”

When running on a glacier, any condensation—sweat, spit, or breath—quickly forms into ice. But unlike many of the other participants who’d practiced in oversized commercial freezers and university-run pressure-controlled units, Tan had trained for the Ice Marathon along the beaches of Santa Monica. At the race, he says, “I wore a silk face muff, and as I breathed into it while I was running, it froze and turned into a ball of ice, making it difficult to breathe.”

“My second lap was the hardest,” Tan said. “It started feeling rough, harder on my legs.”

“I think what makes someone a runner is a mindset,” Tan says. “I can do this. I can run. I can put my shoes on”—Hokas, now—“and take action.”

I met Tan for a run in Palisades Park along the beach in Santa Monica this past April. His black hair hung straight around his neck, pulled back from his forehead by a bandana. He wore Ice Marathon swag—a jersey with a blue outline of the continent in the center. Palm trees lined Ocean Avenue. Tan runs here three days a week. He took his time with me, a casual runner, when I needed to walk. He insisted, despite all evidence, that he’s not an elite runner. “I’m not Boston-qualifying. I’m not Richard Donovan. There are a few hundred people who have run a marathon on all seven continents—not one. But you just run. You put one foot in front of you.”

Tan’s body is tattooed with symbols from his early years in Australia. A black Merlion—a mythical creature with the face of a dragon and the body of a fish, the official mascot of Singapore—swimming in red waves nearly covers his right upper arm. A treble clef dancing in flames bisects his back. A Spanish phrase, vive cada momento—“live every moment”—sits on the inside of his left arm. The name of his sister, Jo, is inscribed on his upper left arm, and below it is a large acorn tree, just like the one that overlooks Byron Bay in Australia, where her ashes are scattered.

Tan is now the president of a local club, the LA Leggers, where he leads the nine-minute pace group every weekend with the goal of bringing more people into the running world. When I joined Tan and the Leggers for a run, he shared a few brief details about various members—their jobs, their kids, their current injuries, the races they were training for. “Community uplifts you,” he told me, “and wants you to reach your potential.”

Tan has built a family with his wife, Stephanie, and their 5-year-old son, Hudson, who can already run more than a mile. For his day job, Tan recently became Director of Innovation at Microsoft; in that role he gives talks on understanding and breaking free from what he calls our inherited limitations. Tan’s own inherited limitations involved the belief that he was not good at sports and never would be.

In the adventure running community, Tan’s outlook holds a particular appeal. “He’s magnetic,” says Randy Boyd, an Ice Marathon companion who has run 46 marathons and 85 half marathons and even launched a bid for governor of Tennessee by running 573 miles across the state. In Antarctica, Boyd recalls, “He was always in the center and people crowd around him. But he’s not loud; he’s genuine and sincere.”

“He has this infectious sort of charisma,” Kennedy, his former roommate, says. “You just feel good being around him.”

Tan rounded out the end of the fourth lap laser-focused on how close he was to achieving his dream. “With almost every mile of the race, I kept reminding myself that this was it, my final continent, and I simply had to finish.” Tears poured out of him, and as he saw the finish line 200 meters away, he couldn’t keep the smile off his face. He fist-pumped the air, pride spilling out of him with each step forward on the ice. The race organizers had set up flags for each runner’s home country, and as soon as Tan spotted the Australian flag, he grabbed it with pride and joy and crossed the finish line in 14th place, with a time of 5:19:31. Tan was one of 11 runners welcomed into the 7 Continents Marathon Club that day.

Within hours, the runners were whisked back to Chile. The conclusion of the marathon felt more like a mad dash off the glacier than a celebration. But Tan was overjoyed. He thought back to his childhood, grateful for his parents’ influence. “One of the reasons I’ve been able to focus on marathons is to get up and show up with the mindset is my parents instilling in me that gift of grit and discipline.”

Since that first run in London, and the marathons that followed on each continent, Tan has been on the lookout for his next big venture. He ponders that question as he runs up and down the palm-lined trails of sunny Los Angeles: Life after Antarctica. What’s left for the man who’s run across the globe? An ultramarathon on every continent.

You Might Also Like