Johnson County’s Negro Creek to keep controversial name, commemorating its grisly past

Despite calls to rename Johnson County’s Negro Creek, a committee has decided to keep the controversial name, worried that removing it would erase a painful piece of history.

Many Johnson County residents spent years unaware of the small, unmarked creek that flows through a golf course in Leawood and in southern Overland Park, in one of the most affluent areas of Kansas’ wealthiest county. But a couple of years ago, activists brought attention to the tributary and the mystery behind its troubling name, calling on leaders to remove it.

The name, historians have discovered, most likely came from a story passed down for generations, of an enslaved man who ran away from the Missouri farm of a prominent and notoriously violent family. The man was tracked along the Blue River as he fled toward Kansas and made it to a tributary across the state line. The story goes that he chose to die by suicide there rather than be recaptured and return to a life of slavery.

“What happened there, as far as we can track down the history, we need to know it so that people don’t grow up and forget history. There’s too much stuff going on right now where people want to rewrite history. You can’t do that,” said Jay Holbert, president of the Johnson County chapter of the NAACP. “If you don’t stand up for what is right, what are you going to stand for?”

The committee, made up of NAACP representatives, Johnson County Commissioner Becky Fast, the Advocacy and Awareness Group of Johnson County and other leaders a couple of weeks ago unanimously decided to keep the creek’s name, after a two-year study. It is now moving forward with creating signs to place along the creek explaining its history and cultural importance.

The debate over the name marked a generational divide, committee members said, among older Black community leaders who wanted to keep the name as a harsh reminder of the past and younger Black activists who argued the name is too offensive to stay. Adding to that, old maps and documents often referred to the creek by a racial slur.

But as state lawmakers and school boards across the country debate whether to limit curriculum on America’s history of slavery and racism, Holbert said it is crucial to educate the public on Johnson County’s true, albeit gut-wrenching history, rather than whitewash it.

“I think you have a bigger problem when children get older and start backtracking and realize a lot of history has been changed. That’ll create a lot of animosity between people. It’ll cause a bigger division,” Holbert said. “If you’re going to try to change anything, you can’t do it without damaging something else.”

Rooted in racial violence

The creek remained largely unnoticed for decades, although occasionally cursed by golfers losing a ball to it at Ironhorse Golf Club in Leawood.

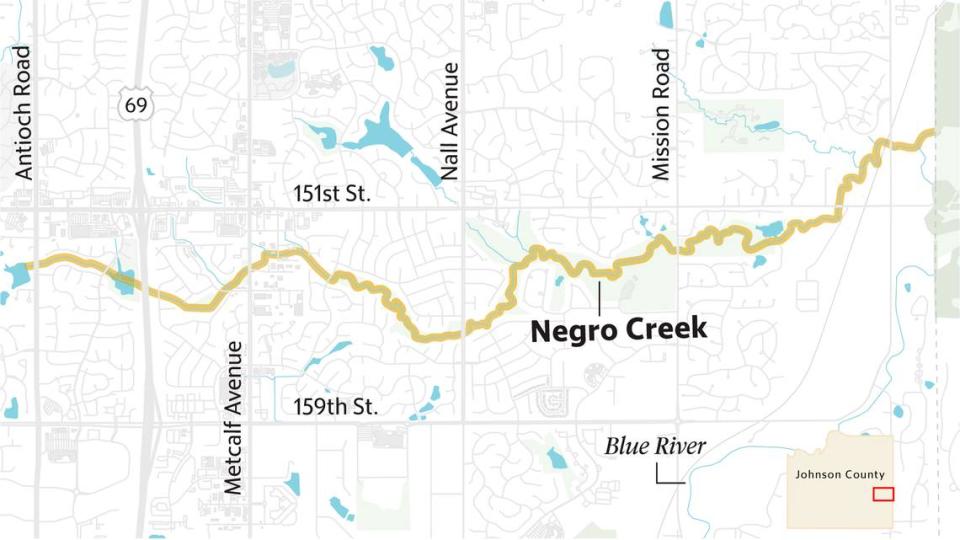

It trickles out of a small lake west of Antioch Road and flows east, over parkland, under Mission Road and through the golf course, ending at the Blue River in Missouri.

And its name has remained a mystery, rarely appearing on modern-day maps. The Johnson County committee recruited the expertise of historians at the University of Missouri-Kansas City, including history professor Diane Mutti Burke, to uncover the name’s origin.

There were plenty of guesses over past decades — perhaps the creek was named after the Black families who lived in the old Oxford Township or maybe it served as a route on the Underground Railroad. But researchers found little evidence to back those ideas up.

The name dates to at least the 1850s, historians at the Johnson County Museum have said, after seeing it first listed on a map in 1856, two years after Kansas became a territory — although it was not drawn to scale. They also discovered that the creek was first mentioned in a newspaper in 1879, but was named using the epithet.

A column in the Western Progress, a Spring Hill newspaper, led researchers to believe that the name is likely rooted in slavery and racial violence.

It read:

“Stanley is located at the head of ‘(epithet) Creek.’ Some of the curious may want to know why the stream is called by that name. As the poet would say, ‘thereby hangs a tale.’ In 185--, James Chiles, of Jackson count, Missouri, had a negro man to ‘run off,’ they followed and surrounded him on the stream running to Stanley to Blue, when finding they would capture him he drew a knife and cut this throat from ear to ear. From that day to this it has been known as (epithet) Creek.” Of course the proper name is negro, but we being Democrats down here, (for short) spell it with two “g’s.”

The wealthy Chiles family was well-known in the region, and many family members lived in southwestern Jackson County near the creek. Col. James C. Chiles was a slaveholder and politician in Jackson County, who pushed to make Kansas a slave state and organized the settlement of pro-slavery migrants. His son, James J. or “Jim Crow” Chiles, married Sarah Ann Young, the sister of Harry Truman’s mother, Martha Ellen Young.

James Chiles was an infamous bushwhacker who was reportedly connected to several murders. The family enslaved more than a dozen people in the mid-1800s, including some young adult and teenage men, according to census records.

Because of the family’s prominence, UMKC researchers felt it plausible that such a story would have been known and passed down in the region. And it is likely enslaved people followed the Blue River into Kansas territory.

Fast said committee members have worked to find the name of the enslaved man, possibly to rename the creek after him, but had no luck.

“On census records, if you’ve been enslaved they don’t keep your name. We see that with (the Rev. Thomas) Johnson, (our county’s) founder, there are only first names on census records for some of his slaves,” Fast said.

The Spring Hill newspaper column came 20 years after the suicide. And researchers struggled to find more information during the COVID-19 pandemic as historical archives were closed. That’s partly why the study took so long. But despite several details remaining unverified, historians feel confident the story is the most likely origin of the creek’s name.

In 1993, the Johnson County Sun said that there was a local legend that a “black person was hung near the creek.”

And researchers said there is often a history of racial violence behind such geographic features. There are at least six in Kansas containing the word “Negro” in their names, including some creeks. One southwest of Wichita comes from a story of a Black man who froze to death in a blizzard near the stream in 1872. A newspaper reported that one in Atchison County was so named after the lynching of a Black man. One that flows into the Arkansas River near Wichita is named for four freedom-seekers who were killed or wounded there.

Officials removed the racial slur and changed the names of many of these places to “Negro” after a federal mandate in 1963.

‘Preserves that history’

After the committee began studying the history of Negro Creek, Fast said community members submitted about 65 ideas for a new name, such as Freedom Creek or Prairie Creek.

But Fast said none of them felt appropriate.

“If you change it to Prairie Creek or Green Creek, then it’s not historically relevant. To find a historically relevant name, many people suggested Freedom Creek. Well, we don’t know if that was a freedom creek or if someone lost their chance at freedom there,” Fast said. “The committee came to a 100% consensus that by keeping the name, it preserves that history. No one wanted to lose that history.”

That’s a stark change from two years ago, when Fast told The Star there was “a total consensus” that the name needed to change. “You can’t run from the past, but you can use it to better who you are now,” she said at the time.

Several other officials were pushing for the name to change that year. Kenya Cox, then-executive director of the Kansas African American Affairs Commission, said that younger generations “perceive it as a derogatory term.” She added that since in 2013, the Census Bureau decided to stop using the word on its surveys, then perhaps maps should remove it as well. The following year, the U.S. Army dropped the term from its equal opportunity policy.

The UMKC researchers also recommended the creek be renamed after studying its history, saying in their report that “there is enough evidence to show that the name of this creek originated with slavery and racial discrimination.”

“In addition, it is well documented that into the 20th century, local residents of Johnson County repeatedly referred to the creek by the racial slur rather than the word “Negro.” Again, this supports the idea that the name was not meant to be laudatory and is enough to recommend changing the name of the creek.”

But historians urged the county to use the process as an opportunity to “reckon with the many troubling and tragic parts of this history.

“It is essential to engage in the restorative work of uncovering the lost stories of Black Johnson Countians’ experiences, which include the history of slavery, segregation, discrimination, and racial violence. This essential and important work could provide a space for increased understanding and continuing conversations as you work to improve the lives of all the people of Johnson County,” the researchers wrote.

But Fast told The Star on Monday that the committee ultimately decided changing the name to something noncontroversial would make it easier to overlook the creek’s history.

Officials decided against trying to change the name, which would require federal approval and community consensus. Holbert also said it would be costly to change the name on maps and county documents.

“This way we can keep the name, leave it alone, save the money and make people aware of what’s going on,” he said.

Fast said the committee will meet with city leaders and other stakeholders to place plaques along the creek citing its history, including the theories behind its name.

She said it’s possible the federal government could someday force a change to the creek’s name. Secretary of the Interior Deb Haaland a couple of years ago ordered that an offensive term for Native American women be replaced on geographic features and federal lands. Before that, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 2017 renamed wetlands north of Kansas City to Loess Bluffs National Wildlife Refuge.