John Prine Made the Ordinary Sound Extraordinary

John Prine was funny. Really funny. His most romantic song, the most romantic song, includes the couplet “she thinks all my jokes are corny/convict movies make her horny.” Beat that. He was sentimental, too, in a way that intensified the irreverence, and irreverent in a way that intensified the sentimentality. Sometimes these bumped into each other before you even realized what was happening. Take the middle of “Lake Marie,” where one of three intertwined storylines concerns a couple on the rocks: “Many years later we found ourselves in Canada, trying to save our marriage and perhaps catch a few fish … whatever came first.” He was funnier than a guy who wrote some of the saddest songs in the world had any right to be.

His saddest, “Hello in There,” a glimpse into the loneliness and isolation of old age, is a wrenching listen on even the best days. It is near-impossible when we’re in the middle of a pandemic that is disproportionately targeting the elderly. A pandemic that got Prine, too, at the age of 73.

He had been through it already. Cancer in his neck damaged his vocal cords in 1998, lung cancer in 2013 took part of one lung. You wouldn’t know it seeing him on stage. The last time I did, almost exactly a year ago in Brooklyn, he came on early and played late, cracked jokes and danced spiritedly. At one point he brought his wife Fiona up to share the mic. It was the best show I’ve been to since God knows when. The room was incandescent with joy.

I have a theory that there is no such thing as a casual John Prine fan. Prine won Grammys, the admiration of critics and peers, and influenced a whole generation of new country musicians. He is a favorite of Bob Dylan’s, who, in 2009, called his songs "pure Proustian existentialism. Midwestern mind trips to the nth degree.” (“Proustian existentialism?” Prine responded a year later. "I can’t even pronounce that.”) But he didn’t have many mainstream breakthroughs. If you’ve been exposed to one of his more popular songs and dip into the rest of his catalogue, it’ll be a minute before you emerge, feeling like you’ve been let in on the world’s greatest shared secret. I can still viscerally remember the moment it happened for me, hearing “when I was a young girl well, I had me a cowboy, he weren't much to look at, just a free rambling man” softly playing in the background of my sophomore dorm. I asked my roommate, who had been introduced to Prine’s music through her father, to tell me the name of this man singing with such plaintive longing from the perspective of a middle-aged woman because I wanted—I needed—to hear everything else he had ever recorded.

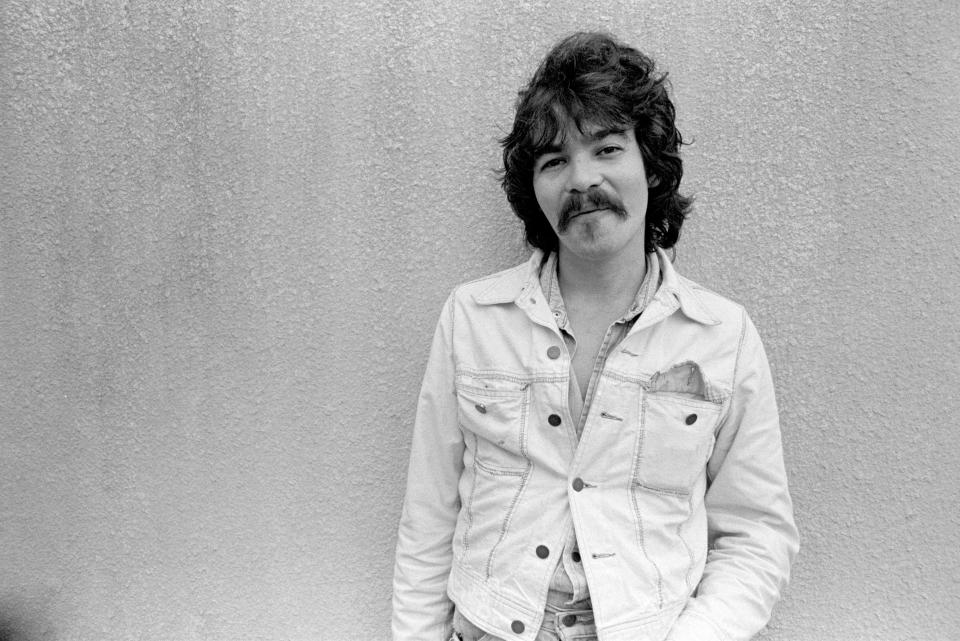

John Prine on campus of Georgia State College - November 12, 1975

Nobody wrote about the interior lives of ordinary, imperfect people—their dreams and disappointments and endearing eccentricities—the way Prine did. After all, he was an ordinary person. Born in Chicago, the son of proud Kentucky natives, he was drafted into the Army around the time of the Vietnam War but sent to West Germany to work as a mechanical engineer. (He was lucky, but had more friends who weren’t, inspiring wry, searing songs like “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get You Into Heaven” and “Sam Stone,” and a political streak that would crop up over the years.) Prine returned to the Midwest and worked as a mail carrier, writing and performing on the side. His first review came from a young Roger Ebert with the headline “Singing Mailman Who Delivers a Powerful Message in a Few Words.”

John Prine, his first album, was released in 1971 by Atlantic records after Kris Kristofferson introduced Prine to audiences in New York. It is a perfect album, warm and witty, a little dirty, more than a little devastating. I can’t let myself write about Prine without mentioning “Spanish Pipedream,” in which a topless dancer dispenses advice in the form of a hippie call to arms—“blow up your TV, throw away your paper, go to the country, build you a home, plant a little garden, eat a lot of peaches, try and find Jesus on your own”—because I can’t listen to that twangy chorus without wanting to take a Molotov cocktail to my flatscreen and book it to the Hudson Valley.

"If you dip into the rest of his catalogue, it’ll be a minute before you emerge, feeling like you’ve been let in on the world’s greatest shared secret."

What still floors me is that this young man, not yet 25, was able to reach across generational and gender lines to write songs like “Angel From Montgomery” and “Hello in There,” teeming with tenderness and compassion. He would continue, for a half century, to produce music that delights and digs deep. By his last album, 2018’s Tree of Forgiveness, he had arrived or passed the age of his characters in those early songs. It wasn’t as bleak as he had imagined decades earlier, and he had big plans when he got to heaven, anyway: he would get his hands on a vodka and ginger ale cocktail, a pretty girl, and “smoke a cigarette that's nine miles long.”

When my husband and I got married last year, the idea of expressing emotion in public was more than vaguely embarrassing to me. At the same time, a wedding wasn’t something I could approach with my default ironic distance. How lucky we were, then, to have the most romantic song at our disposal for our walk back down the aisle: “In Spite of Ourselves.” Prine’s 1991 infinitely catchy duet with Iris Dement is about two ordinary, imperfect people who, despite being ordinary and imperfect, know that the other is “the big door-prize.” It is beautiful and it is profound and, best of all, it is really, really funny.

Music

Prine’s new record proves he hasn’t missed a beat.

Originally Appeared on GQ