John Lurie, Downtown Icon, Is Living His 26th Life Like It's His Last

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Eric Mockus

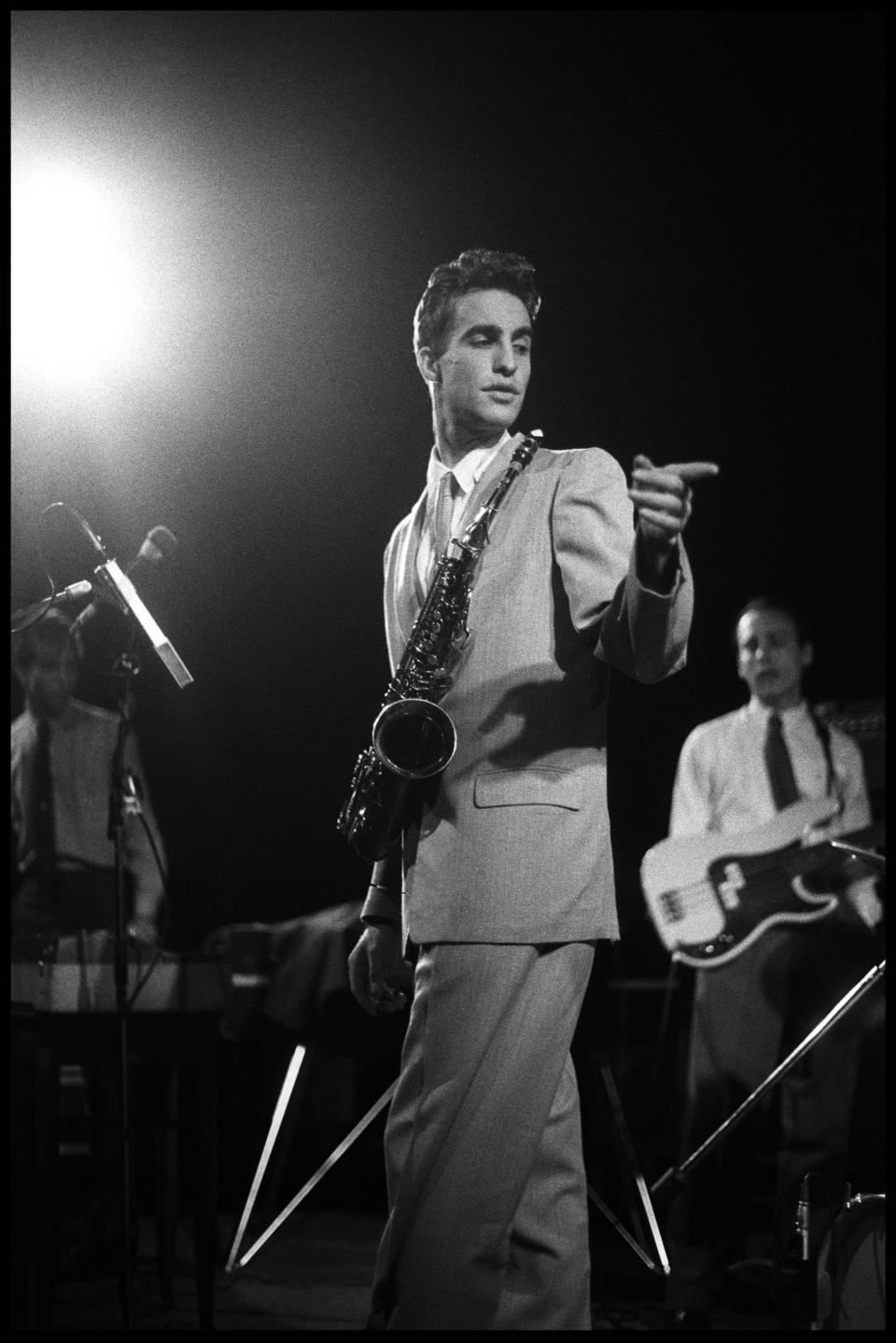

If you’ve never heard of downtown New York legend John Lurie, his pitch for the TV show he wants to make next is a good place to begin getting to know him. “I want to make a bucket list show where I actually go and do the things I want to do before I die, like see a tornado and learn how to surf,” he explains to GQ. We laugh, before he clarifies: “I’m actually making this. It’s called I'm Old and Sick and You Are Horrible People.” At 71, the filmmaker, painter, actor, and musician has lived 25 lives, and he’s intent on living a 26th before he runs out of time. He has been a rabble rouser in New York’s always-morphing cutting edge art scene. He was a magnetic force on the saxophone with his no-wave-turned-serious jazz group The Lounge Lizards, a scene-stealer in films from David Lynch, Martin Scorsese, Wim Wenders, Jim Jarmusch, and more. He created a cult classic Bravo/AMC series called Fishing With John, which found such a concentrated yet devoted audience that the Criterion Collection released it on DVD.

Then, John’s life fell apart. He contracted advanced Lyme disease, and spent all of his energy avoiding the side effects of the treacherous disease. He wasn’t making music; he could barely even listen to it. Over the decade plus that followed, Lurie’s life returned to some normalcy, and he became strong enough to return to New York from a remote island in the Caribbean that he refused to name, although Reddit sleuths are convinced they’ve solved the riddle.

A healthier Lurie signed up with HBO to make Painting With John, a spiritual sequel to his cult classic that earned rave reviews and ran for three seasons before being canceled. Now, Lurie has sifted through his archives to create a 56-song soundtrack that features music from the show and his entire discography. There are solo pieces, songs from his alter ego Marvin Pontiac, and songs he’d rather not talk about at all. In fact, there are many things John Lurie doesn’t want to talk about, and even some of the things he does talk about (or, more accurately, posts about on X) get quickly deleted, sometimes after he receives death threats in response. But he’s used to that—really, there’s nothing John Lurie isn’t used to. He’s old. He’s sick. We’re all horrible people.

Hey John, how are you?

Are you calling from L.A.?

No, but I’m from there.

Yeah, I had a number from there one time.

Did you live out here?

If you strung out all the time, I lived there for about a year and a half, two years. I had a girlfriend who lived there and I lived with her for quite a while. I've done different projects out there. I've spent a lot of time out there. Maybe it's more than two years.

Do you like L.A.? I feel like you wouldn’t.

I had one trip there about three years ago. I don't know, maybe even longer. And I loved it. The air was perfect. The air was definitely better. When I used to go there, it'd be like walking into the back of a laundromat. The fumes and the air would burn your eyes. But I'm talking about 30 years ago. It was really awful. Whenever I did Marc Maron I was back out there [2016], and the air was just lovely. Also, everybody was really kind. It was a really good trip. I thought, “I'm going to move here.” But then I went back a couple times and I said, “I'm not going to move here.”

I always feel discombobulated there. I can go from Kenya to Tokyo to Brazil and to New York and feel fairly comfortable. But I have culture shock or something in LA. I feel odd. If I'm in a restaurant, I'm always looking around and I feel like everybody knows something in LA that I don't know.

Well let’s talk about some music. How did the process for collating all these songs from all these different eras of your career come about?

So many people were saying, ‘you have to do this,’ There’s three seasons of Painting With John. In the first season, we used existing material that would work for the show, particularly for the painting segments. There’s one where I'm rolling tires down a hill called “Vibe Whoops” that I like.

How do you assemble 56 tracks of music?

I mean, that was a thing. There was actually four hours of music, so cutting stuff out was really difficult. It was really, really difficult. It took quite a while to assemble this and to get it into a sequence that worked. I'm really happy with the sequence now, and I really want people to listen to it at least once. Although I know people don't do this anymore, I implore people to listen to the digital version all the way through from beginning to end without interruption and without just listening to one track. I really made it so you can listen to the whole thing all the way through. If you listen to the way through uninterrupted, when you finish, you'll be a better person. That's a joke. You're supposed to laugh there. But wait, I think I've lost your question entirely.

I think it might have made me a better person?

Good.

Maybe there's some truth in your joke.

There is some truth, but you're supposed to laugh. Otherwise I can come off like a pretentious asshole.

But about the album, I feel like it's got a purity to it. Especially with what's going on in the world, I feel okay putting it out. It's like how can you even put something so frivolous as music out into the world with what's happening? I made sure that, at least for me, the world would be better with this recording in it.

I feel guilty for wanting to disassociate from the constant horror, but I do it.

I do that a lot. I do that with sports in particular, but then if you get Tony Romo, Doris Burke, or Reggie Miller, they ruin it. I hate that they ruin the games for me, and I need those games to just dissociate from everything. I feel like it's a personal affront that Tony Romo is allowed to broadcast games.

I grew up a Knicks fan, so I have a deep, deep loathing for Reggie Miller.

But it's not like that for me. I don't even think of him as a ball player anymore. He's like the kid that nobody wanted to hang out with. ‘Hey guys, what's happening? Golly.’ He adds ‘now’ to the end of every sentence, too. I think he should get an electrical shock every time he says ‘now’ at the end of a sentence.

Do you have a team you root for?

I root for whoever's behind.

I get great joy from reading your Twitter, by the way.

Thanks. I delete a lot of them.

Well, the ones that are up are quite funny.

I used to get death threats and stuff. I would put stuff up for an hour and then take it down, because the death threat people seem to read very slowly.

We keep changing the subject, we should talk more about the music, because I think the music is special. The new songs can operate as a soundtrack or on its own as well. Is that something that was top of mind when you were recording?

It had to be organic, and that's where the sequencing comes in. How do you have music made 30 years ago alongside music that was made last year? Well, I mastered it like 10 times to get it right, also because the volumes were different and the sounds on different kinds of recordings were hard to match it all up. But I'm talking about the whole thing, listening all the way down, and I don't think anybody does that anymore. Everybody just buys one song.

It's hard to manage tone and theme across almost 60 songs, but you do a remarkable job of keeping things coherent, even in different modes.

Somehow I pulled it off. It took weeks to really get it together, and then you had to listen to the whole thing all the way through every time you mastered again. That was kind of daunting. I didn't want to get to the point where I was hating my own music because I heard it too often.

I knew there was a long period where you couldn't really listen to music. Are you much more active as a listener these days?

Well, it never really came back. I mean, because I got Lyme disease, advanced Lyme Disease, or chronic Lyme disease, I was a neurological mess. I couldn't handle any chemical cleansers. Fluorescent lights were a problem and not because of what it did to my eyes, but the sound of fluorescent lights would wreck my nervous system. My sympathetic nervous system would just pick up on things and I couldn't listen to music at all. We're talking a long time ago, 20 years ago, and I got better, but I couldn't play the saxophone and I couldn't listen to music. Music became this thing that was just a horrible tragedy and I lost it.

I never dealt with the trauma of losing music then. First, I bought this little hundred dollar acoustic guitar and would just mess around, or I would pick up the harmonica from time to time, slowly, slowly, slowly. Iit doesn't cause severe neurological problems that it did at one time, but I need to take listening slowly. Pretty much all I listen to is from Africa. I listen to Fela [Kuti], Ali Farka Touré, things like that. I don't listen to much else, some things just move me too much.

It's just too intense of an experience?

Yeah. I can put on music that I can move to, but not that I'm just going to sit and listen to unless somebody comes along that I really trust, ‘you have to hear this new thing,’ then I'll listen. But that happens very, very rarely.

What is your connection to African music in particular? Obviously, Fela is a genius — maybe my favorite musician ever — but what in particular about its history moves you?

I don’t know how it’s not everybody’s favorite music. But it started with the Lounge Lizards. We went on our first tour in Europe in 1980, and we were working with this guy who was also Fela’s promoter. On the bus, we had a video player and there were all these videos of Fela playing live, you know, with the 18 wives and stuff. It was so noble. The early band was a punk-jazz band. We were completely irreverent and wild. We were breaking all the songs on purpose. We were a bunch of wise guys and then you see this thing that’s really noble, and it’s, ‘Well, I have to strive for that. It just seems real! It just seems like they’re playing music for the right reasons. I was in The Last Temptation of Christ and almost every American in it was miserable being in Morocco but I loved it. I was in Morocco and I met this French gypsy who told me I had to listen to this nomadic music from these guys who travel and live in tents, called Gnawa musicians. They played music for the exact right reasons. It was inspiring.

Did you ever see Fela live?

When I finally got around to catching him he had been in prison and they had broken him. He was up on the front of the stage smiling with this big weird, shit-eating grin. The musicians behind him were sneering at him and making jokes behind his back. The prison broke him.

It's kind of worse than not having seen him at all, in a way.

Definitely. It was heartbreaking, because of how amazing his work was.

There’s a quote around this album, that if this is the last thing you do, you “want it to be beautiful.”

Maybe I should have stopped short of that. This won’t be the last thing I do.

But you’re reckoning with legacy, I imagine.

Everything I've ever done is like, “Well, if this is the last thing I ever do I better make it really soulful.” I guess that made it seem like I'm going to die next week or something. I’m not, I hope, but this project does have soul.

Do you reckon with your legacy at this point in your career?

I used to think about how I'll be remembered, but I don't think humans are going to be around so much longer. It used to be quite a different thing. You'd work on a piece of art and think, “How will history see this?” But now it just feels like these are end times, and so the perspective changes. If something lasts a hundred years, it gives it a stamp of approval that it's still around. A hundred years from now, it seems unlikely there will be anything. Jesus, what a depressing answer. I had to do Painting With John because there were things about me in the world, from a magazine article that I couldn’t live with. I didn’t want these things to be the last things people remembered about me. Things that were absolutely untrue and quotes I didn’t say.

When I was living on an island by myself before I started actually doing things again, I had to prove to people I wasn’t the asshole I was portrayed to be. Like, “This painting's too beautiful to be done by that asshole.”

Do you want to elaborate on what that was?

I don’t.

Marvin Pontiac makes a return on this record too. What's your relationship with the character like at this point?

I think the hoax is pretty much blown open now. How do you pronounce your last name?

Shoo-bee.

I didn't expect that. When you write a review of country music, you're kind of a different Will Schube than when you write something on hip-hop, right?

Yeah, certainly.

It's the same thing. When I'm in the Marvin mode, it’s a little sillier, a little wackier. I kind of doubt there'll be another Marvin record, but maybe there will be. It's just a voice in me that I hide behind a little bit. It’s nice to put a mask on and have a character to play. have a character to put a mask on.

How do you remember Fishing With John? Do you think about it fondly?

It seems to be viewed now as some perfect thing, which is okay. I don't watch it. Like with music, I only hear the mistakes. It's not quite as bad with a TV show, but you still see the mistakes. It was hard. It took a number of years. There was a legal mess that went with it, and when we first shot it…it's too complicated to explain, but all these companies thought they owned it. People around me did some really sneaky things. It was awful. So, it took seven years to get it out. I think some episodes are much better than others, with the Willem [Dafoe] episode being the best of them.

It's an all-timer.

Oh, good. Almost everything I do 20 years later is considered really important. When I do it, nobody wants to have anything to do with it [laughs].

It’s kind of funny to laugh about in hindsight, but I imagine it was rather frustrating in the moment.

When Season 1 of Painting With John did well, I was happy. It got 100% on Rotten Tomatoes; but then season two got zero press and HBO sort of seemed to sort of shuffle it off to the side a little bit. Nobody knew it was on, but I still did it.

I guess what was shocking to me was working on Last Temptation of Christ, and Marty [Scorsese] didn't have nearly enough money to do it how he wanted to do it. It had taken him years to do it. Damn, Martin Scorsese goes through this — struggling to get money together? Shit, it’s the part I hate. It’s like filling out insurance forms. I can’t stand the business of it.

You just like to make shit.

Yeah, exactly.

Is there a movie from the past year that you particularly were moved by or really loved?

I didn't mind the Giamatti one. I didn't mind it, but I didn't love it. Oppenheimer was very good. I liked that one.

There’s a lot of stuff you didn’t want on the record during this conversation. I’m wondering the reason behind that.

I tried to be as honest as possible in my memoir, The History of Bones, and it made some enemies. People I liked. So I’m trying to be more careful.

Are you still friends with any of your old collaborators?

I am much more of a hermit these days. I am still really close with Flea and it really warmed me to work with all the musicians again. That was a very nice opportunity.

Originally Appeared on GQ