Will Joe Biden or Donald Trump Actually Call the Other to Concede the Election?

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

In the final days before November 3, as Donald Trump and Joe Biden battle it out for the presidency, there is much we do not know: whether results will be available on election night, what the Electoral College map will look like, and whether a candidate will take their case to court. Something else we don't know? Will the losing candidate actually contact the winner to privately concede the election, like many have done before, starting in the late 1800s? And, will the losing candidate give a public concession speech, as became common in the mid 20th century?

Election night phone calls and concession speeches have not always been amicable, but the actions are seen as a kind of political etiquette, a recognition that the fight is over and there is governing to be done. You could call them acts of political decency, and even if they are not legally required, they have become a tradition that the public looks for and that history remembers.

Here's everything you need to know about when candidates starting publicly and privately admitting defeat, and what this year's concession might look like, if it happens at all.

The earliest election concession "call" was actually a telegram.

In 1896, William Jennings Bryan was the first losing candidate to contact his opponent and offer his congratulations. In his memoir of the campaign, Bryan wrote that he telegrammed president-elect William McKinley on November 5, two days after the election, when it became clear that he had lost: “Senator Jones has just informed me that the returns indicate your election and I hasten to extend my congratulations. We have submitted the issue to the American people and their will is law.” McKinley soon telegrammed back to acknowledge the message and thank him.

And so, a political tradition was born. For much of the early 20th century, the custom remained: a private, olive-branch telegram sent from the loser to the victor, but no public address.

Still, not everyone adhered perfectly. In 1916, Charles Evans Hughes waited two weeks before telegramming his concession to Woodrow Wilson, who cracked that the message was “a little moth-eaten when it got here but quite legible.” Franklin D. Roosevelt was apparently very insulted when Thomas Dewey never sent him a telegram congratulating him on his reelection in 1944.

The first concession phone call came in 1968, but telegrams were still sent into the 1970s.

Concession telegrams remained popular (and their contents private) for half a century after William Jennings Bryan's initial dispatch, and it wasn't until 1968 that a candidate actually got on the phone.

After losing to Richard Nixon, then-Vice President Hubert Humphrey revealed in his concession speech (given at 2:30 a.m. in the Hall of Nations at the Leamington Hotel in Minneapolis) that he both sent a telegram and phoned Nixon.

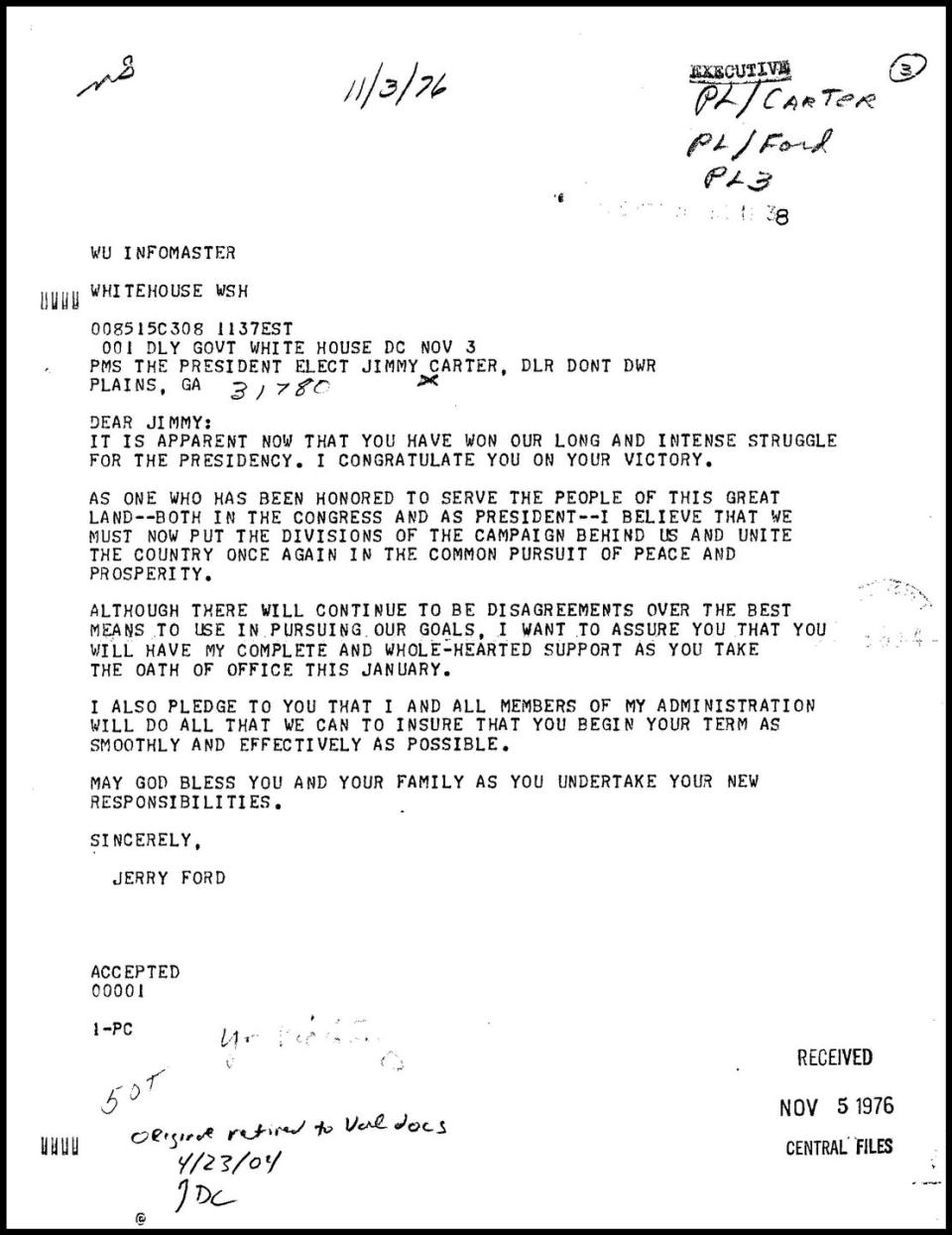

The phone call has now become commonplace (although, into the 1970s, some still sent telegrams, like President Ford did when he lost reelection to Jimmy Carter in 1976.) And, one candidate, George McGovern, still resorted to a telegram when he couldn't face dialing Richard Nixon after he suffered one of the biggest defeats in American history, a 520 to 17 Electoral College blowout.

Public concession speeches were not common until the mid 20th century.

Al Smith, the four-term Democratic governor of New York (and the first Catholic to run for president on a major party ticket), is considered the father of the grand tradition of the election-night concession speech. Smith lost to Republican Herbert Hoover—who was then the Secretary of Commerce—in a 444 to 87 Electoral College wipeout. Smith promptly telegrammed Hoover to offer his congratulations, but also gave a public radio address to his supporters.

This marked a new point in election-night decorum. The concession speech became a courtesy expected of the loser: a show of good faith in the electoral process and acceptance of the results.

The first televised concession speech was given in 1952 by Adlai Stevenson, who had lost brutally to Dwight Eisenhower in a 442-89 vote landslide. Stevenson's gracious remarks are often looked to as a model.

Over the years, a sort of formula developed in the public concession speech: first, the humble acknowledgement of defeat; next, a call for national unity and an end to the election-cycle drama; and lastly, a pledge to accept the will of the people by supporting the president-elect.

President George H. W. Bush's 1992 concession speech to Bill Clinton, for example, was textbook: "Well, here's the way I see it. Here's the way we see it and the country should see it — that the people have spoken and we respect the majesty of the democratic system. I just called Governor Clinton over in Little Rock and offered my congratulations. He did run a strong campaign. I wish him well in the White House."

There have been contentious concessions speeches.

Though most concession speeches follow a tried-and-true approach (heavy on flowery rhetoric about American values, light on the partisan rancor), there have been wild cards over the years.

In 1964, Barry Goldwater gave an unusually blunt address in the wake of losing to Lyndon B. Johnson. First, he questioned how he could have lost and said he was disappointed in the voting turnout: "it's interesting to me and very surprising to me that the latest figures that I can get do not reach the totals of the 1960 election. I am disappointed in this because I thought that the American people would have turned out in greater numbers than they seem to have done." Goldwater also listed off issues, from Vietnam to Cuba, that he hoped Johnson would address as president—an unorthodox move for a losing candidate.

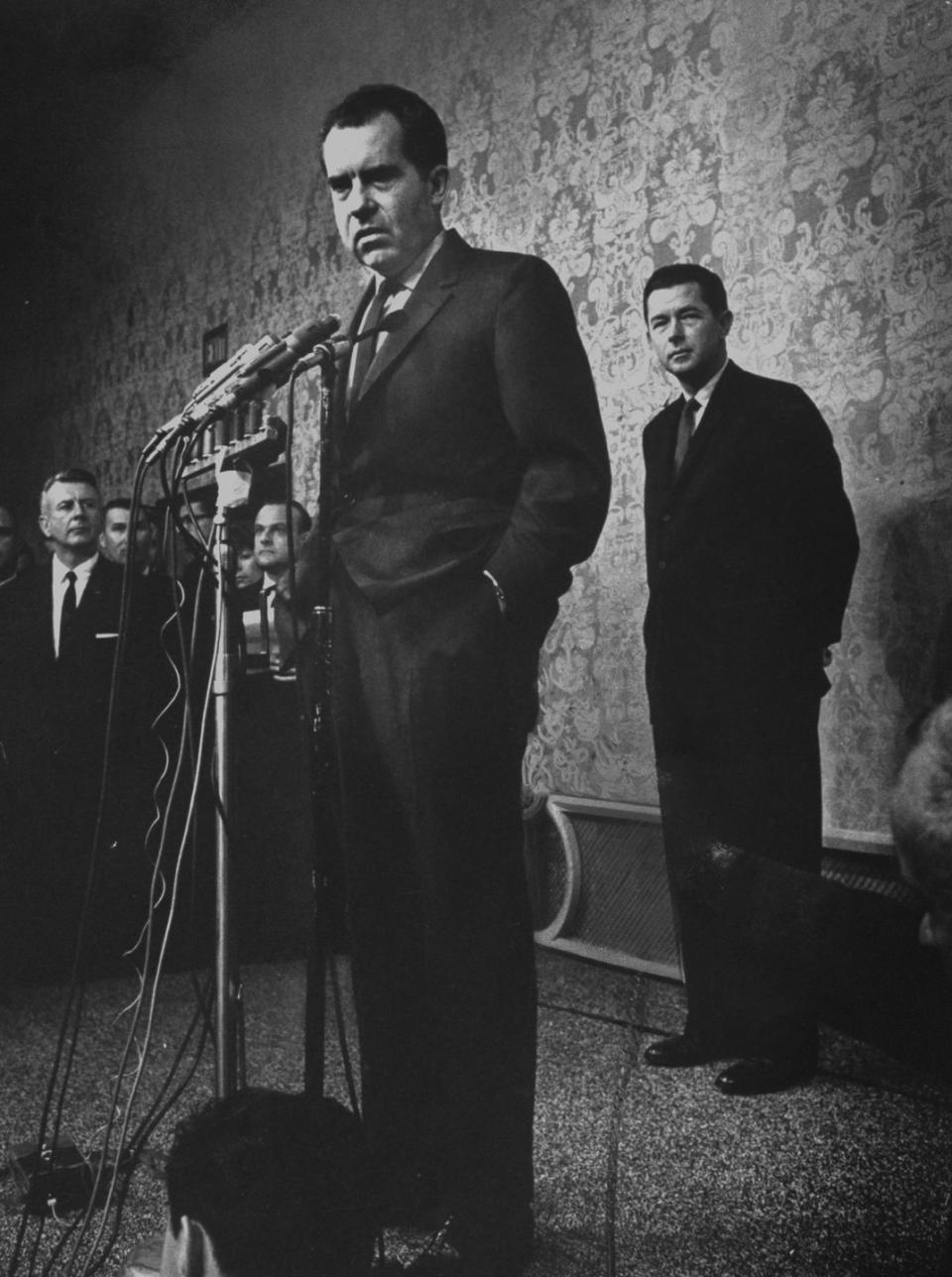

After he ran (and lost) the presidential election to John F. Kennedy in 1960, Richard Nixon ran (and lost) in the California gubernatorial election to Pat Brown in 1962. Nixon gave a smoldering concession speech that took shots at his opponent and the press. "You've had an opportunity to attack me and I think I've given as good as I've taken," he said, adding, "As I leave you, I want you to know – just think how much you're going to be missing. You don't have Nixon to kick around anymore, because gentlemen, this is my last press conference." (Of course, his actual last address would be given 12 years later in 1974, when he resigned in the wake of the Watergate scandal.)

The concession phone call usually goes well—until it doesn't.

Once phone calls became standard, what was said between candidates in those one-on-one interactions has remained mostly private—but there is one infamous exception.

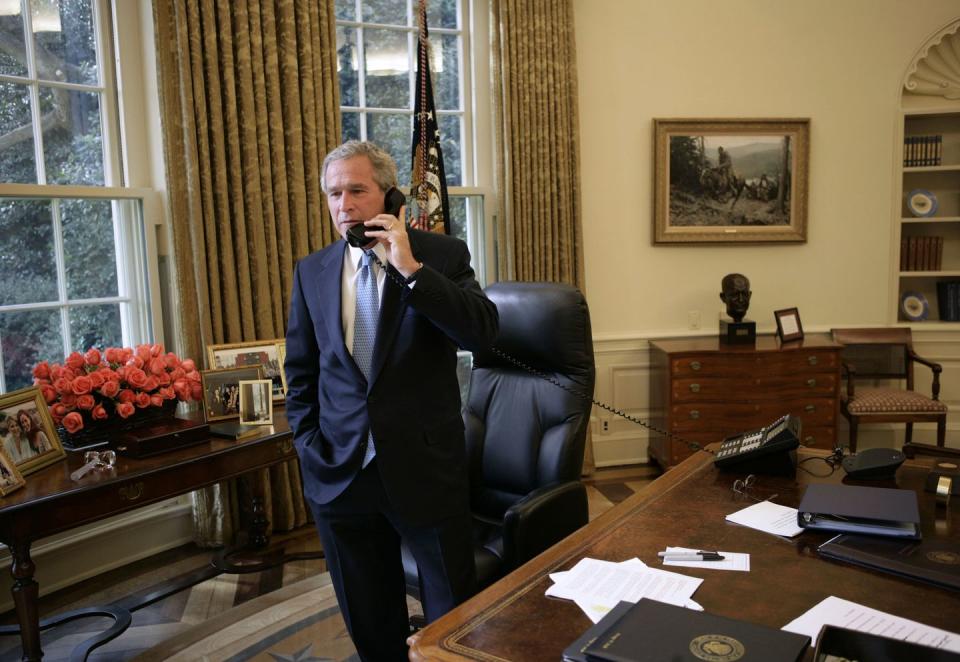

In the early morning of November 8, 2000 after a down-to-the-wire election night as votes were tallied in Florida, Al Gore called George W. Bush to concede, saying 'We gave them a cliffhanger." And then he took it back.

By 4 a.m., the media reported that Gore called Bush once more and said that his Bush's Florida victory margin was “too close to call.”

“You mean to tell me, Mr. Vice President, you’re retracting your concession?” Bush asked.

“You don’t have to be snippy about it,” was Gore's reply.

It wasn't until December 13, after weeks of parsing "hanging chads" and tense litigation leading to the Supreme Court, that Gore finally, truly conceded. “Just moments ago, I spoke with George W. Bush and congratulated him on becoming the 43rd president of the United States,” Gore said in a statement, “and I promised him that I wouldn’t call him back this time.”

Bush later got a much more straightforward election night concession call in 2004, from John Kerry. And so on, from John McCain phoning Barack Obama in 2008, to Mitt Romney calling Obama in 2012, and Hillary Clinton placing a brief call to Donald Trump after his 2016 victory. (In her memoir, she described the call as "perfectly nice and weirdly ordinary, like calling a neighbor to say you can't make it to his barbecue.")

It's unclear what will happen this year.

It's anyone's guess what the 2020 election concession phone calls and speeches will look like—or if they will even happen at all. Given that millions of votes are being cast in absentee ballots due to the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic, results may not be known for days. There may be court cases that take weeks to resolve. And, given the prominence that social media plays in communication, it's possible candidates might tweet short statements over a period of days or weeks, before finally releasing a longer statement.

It's also possible that neither candidate will choose to publicly or privately concede at all. One thing is certain: in the long, strange arc of this election, we can count on even the most benign of political traditions being shaken up.

You Might Also Like