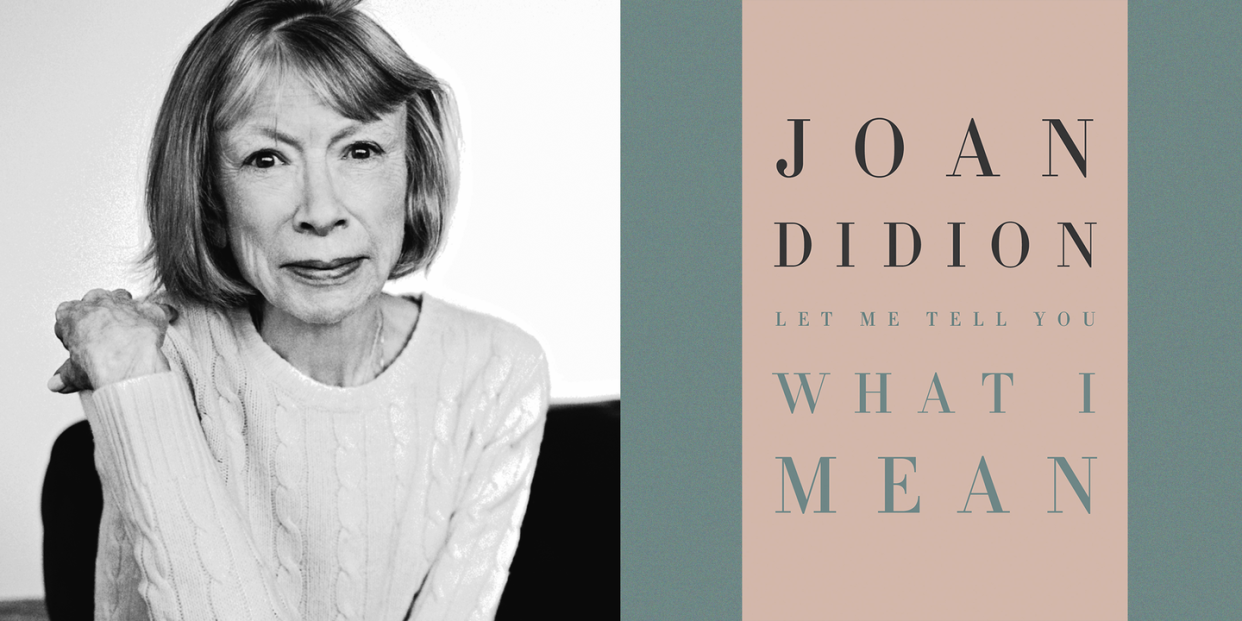

Joan Didion's New Book "Let Me Tell You What I Mean" Shows Off Her Early Work

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

To encounter Joan Didion for the first time, as I did while a senior in high school in the spring of 1983, is akin to knocking back a double espresso: a pulse at the temples, a rush of clarity, a tang of bittersweetness.

Through her work, Didion has conjured a culture that’s dazzling and dangerous, mythic and mundane. Her legacy begins with her early essays on California, gathered in her canonical Slouching Toward Bethlehem and The White Album, and continues to include her National Book Award-winning memoir, The Year of Magical Thinking, which recounts her grief-daze following the death of her husband and creative partner, John Gregory Dunne.

In each of her novels and works of nonfiction, she’s calibrated sentences like a scientist in a laboratory, sifting syntax, centrifugating cadences. Nothing goes unused. As she observes of her mentor Ernest Hemingway: “You care about the punctuation or you don’t, and Hemingway did. You care about the ‘ands’ and the ‘buts’ or you don’t, and Hemingway did.” The same is true of Didion. Hers is the poetry of the flat Western vowels, the deadpan of Hollywood noir. Hers is the stray detail that speaks volumes, the firm conviction in seeing the thing for what it is—the urge to tell the story unadorned, just so.

Now, the new release Let Me Tell You What I Mean, out now, brings together previously uncollected pieces in a prismatic retrospective; the critic Hilton Als charts the arc of her career in a rich foreword that’s almost as long as the book itself. The essays could easily feel like bits from the cutting-room floor, but as usual, Didion exceeds our expectations.

Here, she plays against type, letting down her signature cool reserve, allowing herself to be more vulnerable. In “Getting Serenity” (1968), she drops in on a meeting of recovering gambling addicts in suburban Los Angeles, only to discover she can’t deal herself in. The confessions feel like self-exonerations; the twelve steps grate on her nerves. She craves the open casino of real life, the whir of the roulette wheel: high risk, high reward. And she freaks out: “I got out fast then, before anyone else could say ‘serenity’ again, for it is a word I associate with death, and for several days after that meeting I wanted only to be in places where the lights were bright.”

Let Me Tell You What I Mean follows the chronology of Didion’s publication in journals and magazines, but it shifts back and forth in time as she contemplates the thread of her own life against the tapestry of postwar America. In “On Being Unchosen by the College of One’s Choice” (1968), she quotes her rejection letter from Stanford, dated April 25, 1952, and then segues into a deeper meditation on the status anxieties that plague postwar middle-class families, suggesting that failure is the wisest teacher of all.

A reunion of the 101st Airborne teases out complex meanings of patriotism. Her profiles become miniature social critiques on artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe and Tony Richardson, who both died of AIDS-related illnesses, and the public roles of Nancy Reagan and Martha Stewart.

We don’t associate either Reagan or Stewart with feminist cause célèbres, but beneath Didion’s steely gaze, they claim their own agency. She forces us to see, whether we like it or not, "traditional" women and professional homemakers as far more than the sum of their husbands’ fantasies or handmaidens to patriarchy. In Didion’s Reaganland, for instance, Nancy is the sharper spouse.

She jars us beyond the comfort zones of platitudes and groupthink. Which is hardly altruistic. As she puts it: “Writing is the act of saying I, of imposing oneself upon other people, of saying listen to me, see it my way, change your mind...there’s no getting around the fact that setting words on paper is the tactic of a secret bully, an invasion, an imposition of the reader’s most private space.”

Let Me Tell You What I Mean occasionally feels dated, however, as in Didion’s opening piece, “Alicia and the Underground Press” (1968), a eulogy for alternative papers whose names have vanished from memory. There are treacly moments. But there’s also plenty of vintage Didion: her passion for writing is omnipresent, a compulsion to write about writing, which sparks her finest meditations here. These interior debates about what she does, and how and why she does it, resonate.

She laments her limits as a fiction writer and seems more at ease reporting on the world than creating one on the page. Hence her antennae are attuned to the signal when it comes: “I once knew I ‘had’ a novel when it presented itself to me as an oil slick, with an iridescent surface; during the several years it took me to finish the novel I mentioned the oil slick to no one, afraid the talismanic hold the image had on me would fade, go flat, go away, like a dream told at breakfast.”

Again and again she circles back to her craft. “Telling Stories” revisits her years at Vogue—captured in arguably her most iconic essay, “Goodbye to All That,” a tart valentine to her youth in Manhattan—where she soaked up technique: “It was at Vogue that I learned an ease with words, a way of regarding words not as mirrors of my own inadequacy but as tools, toys, weapons to be deployed strategically on a page...we were connoisseurs of synonyms. We were collectors of verbs.” And Didion the literary critic is a marvel: Her dissection of Hemingway’s opening sentence in A Farewell to Arms is a masterpiece in its own right.

Few if any literary stylists have influenced so many writers across so many genres; in book after book we’ve relied on her elegant, spare work to illuminate the darker corners of America, its flaws and fantasies. We know her. But the Didion of Let Me Tell You What I Mean is also a revelation, as the woman behind the curtain steps forward, more intimate somehow, with flashes of feminist feeling.

Her admiring essay on Martha Stewart could be a coda for her own groundbreaking role: “This is the ‘woman’s pluck’ story, the dust-bowl story, the burying-your-child-0n-the-trail story, the I-will-never-go-hungry-again story, the Mildred Pierce story, the story about how the sheer nerve of even professionally unskilled women can prevail, show the men...the dreams and fears into which Martha Stewart taps are not of ‘feminine’ domesticity but of female power, of the women who sit down at the table with the men and, still in her apron, walks away with the chips.”

Brava.

For more ways to live your best life plus all things Oprah, sign up for our newsletter!

You Might Also Like