Joan Baez Has Forgiven Bob Dylan—Here's Why

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

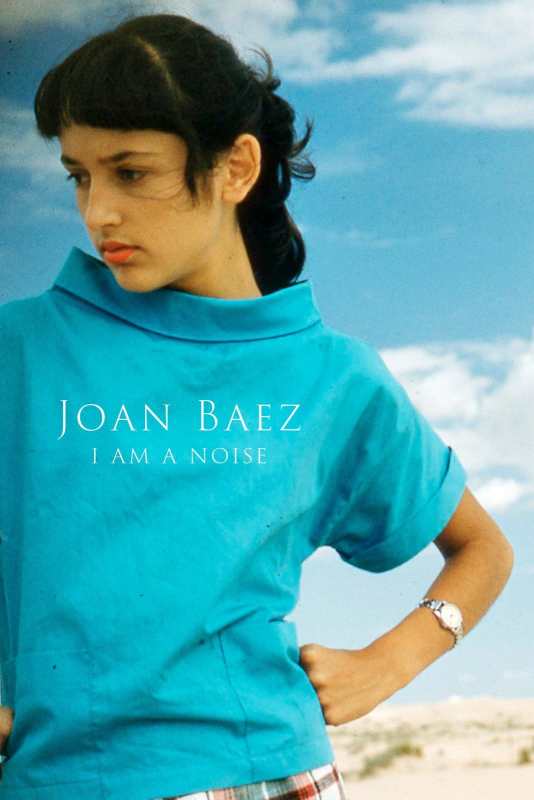

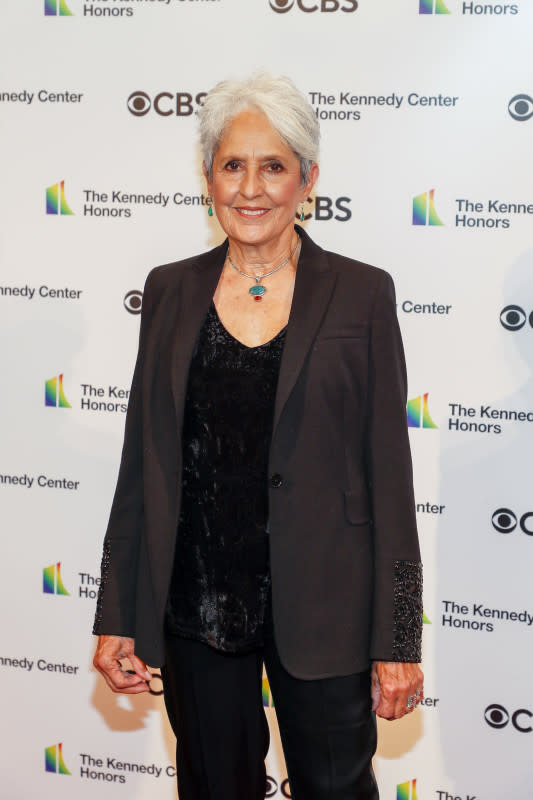

Joan Baez, the “Diamonds and Rust” singer, 82, is known as a caring folk artist who fought for peace and social justice through her music and her actions. But there’s a lot more to her story: Joan Baez I Am A Noise (in select theaters Oct. 13) examines her work and life through a lens that goes beyond the music. From her early childhood to her final tour, it reveals her life through newly discovered home movies, diaries, artwork, therapy tapes, audio recordings and more.

Parade sat down with Baez to discuss the new documentary, but also her storied career as a whole.

Walter Scott: Your activism and your romance with Bob Dylan are well known, but why share now that you suffered from lifelong anxiety and panic attacks?

Joan Baez: I wanted to leave an honest legacy.

When you decided to do this, you discovered a storage unit full of material your parents kept.

[When we were filming], my mom was dying. I gave [the film people] the key to the storage unit. Once I said, “Okay, this is your film,” I didn’t really have any say. So, I didn’t want to hear about it, just take the stuff. I’d never been in that place. In the film when I walk in, that’s the first time I’d ever been in there. It was a combination of an embarrassment of riches and a nightmare for them. There was so much stuff. I figured: Why not be honest at this point in my life? I just had to wait until the family was gone.

Magnolia Pictures

Did you learn anything when you went into the storage unit? Were there things you had forgotten, and it brought back the memories?

Most of it. Some of it, I had no idea existed; some of it I knew about but had never seen before. But the amount of it was overwhelming. I did know about the therapy tapes [from her childhood sessions].

When you revisit your childhood, it wasn’t the happiest, but then you talk about having multiple personalities.

They now call multiple personalities “DID” (dissociative identity disorder). You remember when they first started talking about so-and-so has a split personality? [Mine] was many splits and each one had a reason for being there—each little entity that’s born is there for a reason—when I was trying to grow up. By recognizing these little entities and then nurturing them, that nurtured a part of me that needed that. I loved all the little people in there and they’ve held me together and taught me a lot.

Related: Steve Miller Shares the Stories Behind His Greatest Hits

It was like the movie Sybil where she had fugues and didn’t remember?

Yes. All gone. [The good thing that’s] happened for many people since the film has begun screening is their own traumas suddenly have begun to be something they can actually talk about. That was a wonderful thing for me to discover, that it could influence people to go ahead and talk about their trauma.

Getty Images

You’ve been a fighter for social justice for most of your life. When you look at what’s happening in America now, are you hopeful?

We discussed hope the other day with some smart person who said hope is a practice. I don’t come by it naturally, particularly right now. It’s just the worst anybody could have imagined, where we’ve gone way backwards. I don’t think that takes away from the changes that were made and the courage that went into that. Sitting at a lunch counter and what that meant to people and the bravery, I don’t think you can take that away. You have to recognize it for what it was and try to find a way to deal with what’s happening now. Not an easy thing to do.

We saw you at the March on Washington with Martin Luther King, Jr. and the I Had a Dream speech. That was a very hopeful time.

Yeah, it was. As far as activism goes, it was an extraordinary time and has not been repeated. I think one of the pieces of that is that there’s so much s--t going on right now, you don’t even know which way to turn. Recently in one of the Q&As after showing the film, some younger people said, “What can I do?” I thought, You know what? I don’t know. But I’m certainly going to put together a list of things that might call to them—from gun control to women’s rights to nonviolence, all of it, so somebody can at least look at it and say, “I can tap in there, I can either send money, or I can write letters, or in the end I can really throw myself into it and be willing to take a risk.” Real change is [through] civil disobedience, so you have to be willing to take a risk.

Getty Images

We see you with Bob Dylan and the heartbreaking way it ended with him denying the relationship. Even so, was there something positive that came out of that relationship?

Everything, everything. A couple of years ago, I painted a portrait of him when he was young, put his music on and simply wept for about 48 hours. All of the resentment, all the nonsense. [In the film] when he’s talking about that he doesn’t have any particular girlfriend, we’re so young. He [still has] his baby fat. All of that from the past, I would like other people to release him from that too. When you’re that age, there are mysterious things that make you do what you do and say what you say. I was caught up in it at an early age too. It took me a long time to grow out of it.

When you look back at your music, where did the inspiration for your songs come from?

I guess different places because they would come out of nowhere. I would sit down and think I would write a song about X, but I think sometimes I didn’t even think that, and I would just play the guitar and stuff started coming out.

Was it also a reaction to what was happening in the world that you wanted to speak to?

Some of it was, yeah. Some of it was definitely trying to write a song that had some relevance and the general malaise in the world, the different countries and the different dictatorships and so on. I tried to address that.

Your artwork in the film is a fun addition. You started drawing before you started singing. Why not become an artist?

Once I picked up the ukulele, it dominated. I went on drawing and sketching and so on, and ended up throughout my life doing that, as well. But the voice was, for me, the main ticket.

Getty Images

When you look back, what has made it worth the sacrifices that you had to go through in your personal life in order to maintain the public life?

It’s more about my son [musician Gabriel Harris, 53]. That’s where this terrible sadness comes in that I wasn’t there for him. I didn’t realize the extent of it until I saw the film and I hear him talking. I salute him for being honest and loving and caring but saying what his truth was about growing up with a mom who basically wasn’t there. A lot of times I was there, but I wasn’t there.

Did working with him as an adult, did that help heal the relationship?

It was everything.

Related: 50+ Most Influential Latin American Women in History

You retired from concerts, but are you still involved in music?

Very little. When I say I hung the guitar up, I literally did, on the wall. And then about six months ago, I wanted to do this show with Bob Weir. It was a bunch of people. It took me six weeks to get some calluses back on my fingers. And it’s a different voice, it’s a lower voice, it’s got a lot of gravel in it. As soon as I accepted that, it became possible to go ahead and sing.

Is that a use-it-or-lose-it thing with your voice?

It’s use it or lose it. At a certain point, you’re going to lose it anyway.

So, what’s left?

It’s a lower range and quit fretting about not being able to hit the notes that I want to hit. And then all of a sudden say, “Oh, this could be fun.”

How do you fill your days now that you’ve stopped touring?

I just finished editing a poetry book, which will be out next year. I’m doing a lot of work right now around the film with folks like you and I travel some for that. But happily, we have Zoom. I have 16 chickens and a creek at the bottom of the hill, a lot of oak trees and a lot of that world is where I spend my time.

You’ve lived in northern California for quite a while now. Is it the outdoors that what you love?

Yeah. I realized my family lived right around here for most of my life and I just kind of ended up here and there’s no reason to leave.

When you look back at your life, what are you most proud of?

When you say that, the first thing that comes up is I would like to be remembered as somebody who battled for the rights of my son’s happiness. All the rest of the stuff, fine. But on a human level to recognize his life and wanting to deal with it and be closest friends is a big deal.

Is there something you wish you had more of now?

I wouldn’t look at whatever it is that way. I seem to have plenty of everything.

What has the reaction been to the film from friends and family?

They’re all slightly shocked and pleased. I think everybody’s a little bit stunned at how open I was and the sisters were. It’s just a beautifully made film.

Next, 'Take Me Home, Country Roads'! The Real-Life Stories Behind 15 of the Greatest Songs of 1971