How Jesus was nearly swept away by a wave of unpleasant tales

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

When Jesus was young, another boy bumped into him in the village street. Jesus cursed him – “You shall go no further on your way” – and the boy dropped dead. His parents complained about Jesus to Joseph and Mary: “Teach him to bless, and not to curse; for he slayeth our children.” This was a slight exaggeration – previously Jesus had merely crippled another child – but the plea didn’t work. Jesus cursed them too, and they were struck blind.

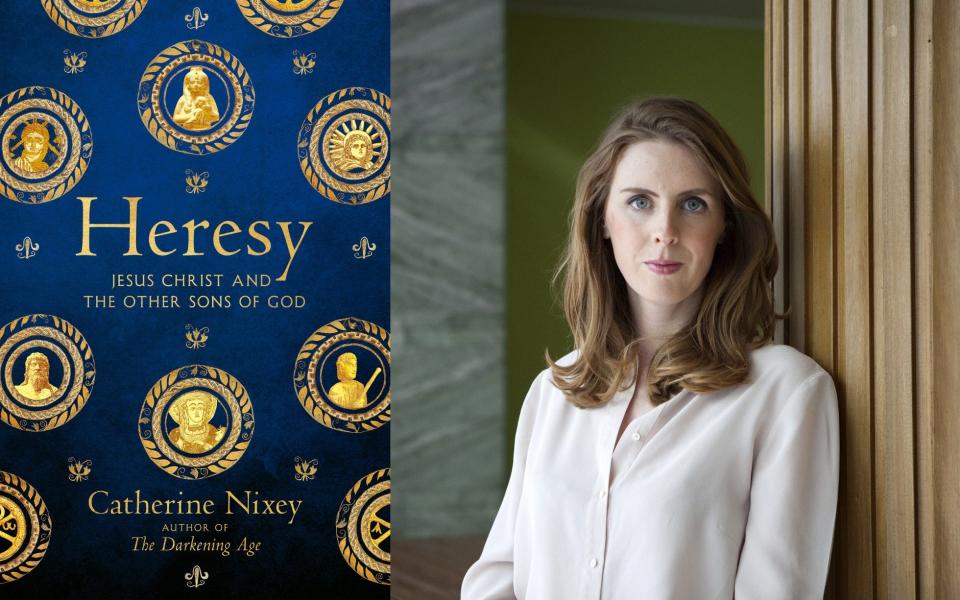

This is not the meek and mild Jesus of the modern Church, but the Jesus of the “Infancy Gospel of Thomas”, one of the so-called Apocrypha. Here, Catherine Nixey starts her enthralling new book, Heresy, exploring the diverse religious landscape of the early Roman empire, in which what ended up as orthodox Christianity was only one merchant in a bafflingly crowded market.

In the first three centuries AD, there were almost innumerable different types of Christians. There were those who denied the virgin birth, the divinity of Christ and the Resurrection. Others thought that the Holy Spirit was female, or that God’s mother was responsible for the Creation. Some worshipped Jesus alongside “Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle and the rest”, while another group worshipped him in the form of a snake. Exhaustingly, one secret sect elevated sex to an act of devotion: go round the track twice with 365 women in view of the congregation, and you could announce “I am Christ”. Nor was the child-killer of the Infancy Gospel of Thomas alone. There were other “bad Jesuses”, such as the one who sold one of his disciples into slavery, or that substituted another victim in the Crucifixion and looked on laughing as the man died.

There were so many different sects, all claiming to be Christians, that modern scholars now tend to refer not to “early Christianity”, but “Christianities”. The sources for these “other” Christianities are mainly obscure and difficult, and fall into three broad categories.

First, the pagans, such as Celsus, Porphyry and the emperor Julian, who wrote works attacking Christianity; mostly these survive only as fragments, quoted in rebuttal by Christian writers. The orthodox Christians, such as Irenaeus, Tertullian and Eusebius, expended much energy in denouncing other Christians they judged to be heretics; obviously they couldn’t be more biased.

And then there are the heretics themselves, including the texts discovered at Nag Hammadi in Egypt, amounting to some 40 surviving Gospels that at some point were labelled “Apocryphal” as orthodoxy fortified its boundaries. Nixey handles all this diffuse and refractory material with aplomb, and good sense.

These versions of Christianity were not just competing against each other. The new pagan cults of Mithras and Jupiter Dolichenus were spreading across the empire from the east. Paganism was not short of divine miracle-workers. Apollonius of Tyana healed the sick, and raised the dead. Once even an emperor joined in: in Alexandria, Vespasian was said to have made a lame man walk, and a blind man see.

So why did Christianity win, and why that specific brand? Scholars have long gone off the idea that Christianity fulfilled people’s emotional or spiritual needs as paganism did not, and its appeal to the poor and downtrodden didn’t turn it into a state religion. In truth, it might be down to a series of lucky historical accidents.

Apart from Nero scapegoating Christians for the great fire of Rome in AD 64, all pagan persecutions were “bottom-up” until the second half of the third century AD: as Tertullian put it, “If there is famine, if there is plague, the cry is at once: ‘The Christians to the lion’”. The Roman authorities would intervene.

But then came the barbarian invasions, civil wars and short-lived emperors of the “third century crisis”. Something had gone wrong with the entire empire, and so with the pax deorum, Rome’s deal with the traditional gods: we do right by you, you do right by us. Two emperors decided it must be the Christians, and ordered empire-wide persecution. Instead, the fate of both men gave Christianity a shot in the arm: Decius was the first emperor to be killed in battle by the barbarians (AD 251); Valerian the only emperor to be captured alive by them (AD 260). And then, before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (AD 312), Constantine saw a vision in the sky: a fiery cross, and the words “In this sign conquer”.

In itself, this wasn’t all that unusual. The emperor Aurelian had seen a vision of Sol Invictus before the Battle of Emesa (AD 272), and previously Constantine himself had had a vision of Apollo. What was unusual, as Nixey ably points out, was the longevity of Constantine (died AD 337), and his sons (Constantius II, died AD 361). Half a century of imperial patronage and coercion would entrench the particular type of Christianity favoured by Constantine and his family.

Only hindsight, then, makes the triumph of that “orthodox” Christianity inevitable. With style, wit and impressive scholarship, Nixey shows how, “had history tilted slightly”, it all could have been so very different. Heresy illuminates a forgotten world – and it’s an absolute pleasure to read.

Heresy is published by Picador at £25. To order your copy for £19.99, call 0844 871 1514 or visit Telegraph Books