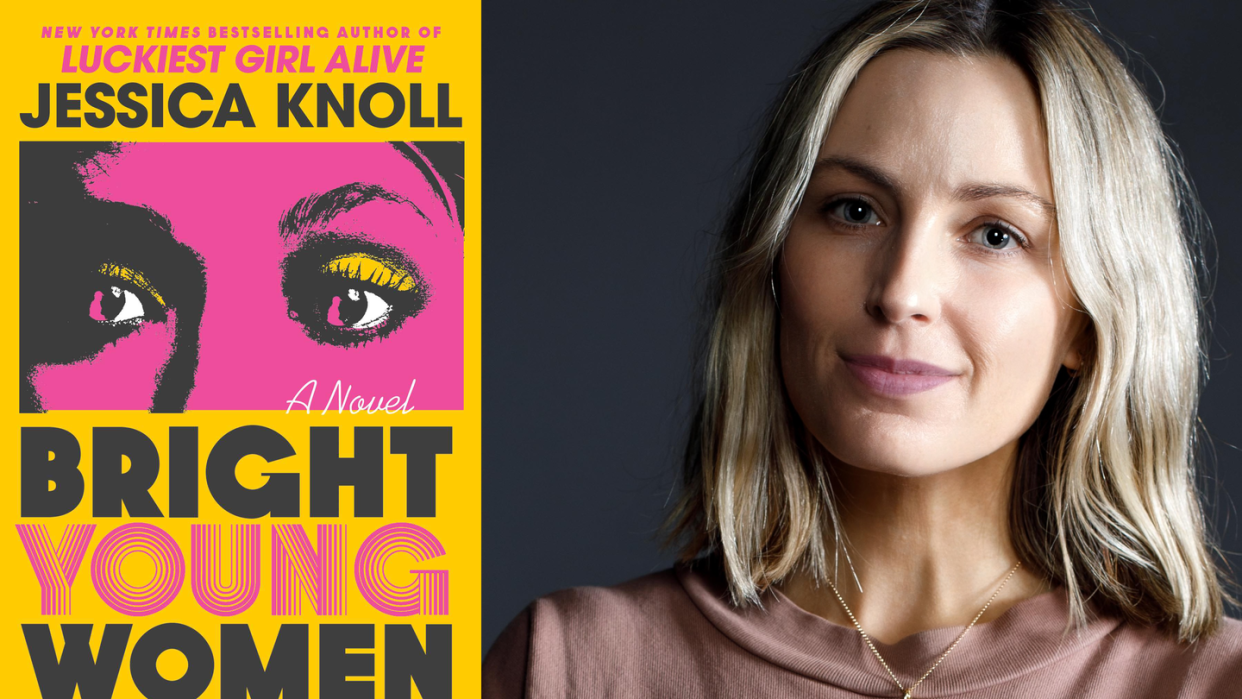

Jessica Knoll’s New Novel Challenges a Serial Killer’s Legacy

True crime is big business. We devour the podcasts and binge the documentaries, sometimes with a twinge of guilt. But as the genre continues to flourish, even its fans are questioning the ethics of rehashing real-life tragedies for the sake of entertainment. Can the right approach to these narratives bring healing instead of potential harm?

Jessica Knoll’s Bright Young Women (out today from Marysue Rucci Books) is a riveting exploration of women whose lives were shattered by America’s first “celebrity” serial killer in the 1970s. And rather than risk glorifying a criminal who was known for having groupies, Knoll actively decenters him by not naming him in the text. He is simply referred to as “the Defendant.” In the same spirit, we’ll also refrain from identifying him to avoid adding another hit to the nearly 10 million search results his name currently yields. Hint: He’s been portrayed onscreen by Zac Efron.

In a conversation with Harper's Bazaar, Knoll discusses why she followed her best-selling thrillers Luckiest Girl Alive and The Favorite Sister with this true-crime-adjacent novel. When she watched a 2019 Netflix docuseries featuring experts who laud the serial killer as a mastermind, she was disturbed to hear the sentencing judge refer to the defendant as a “bright young man” in the courtroom with victims’ families present. “Initially, I knew I wanted to write something that would center the women and talk about how they were bright, they had promising futures. … But what I didn’t expect to find was so much evidence against the narrative that he was a bright young man,” Knoll recalls.

Although the dates and locations reflect actual events, Knoll’s narrative focuses on two fictional women whose lives are altered by the killer: self-reliant Pamela, president of a sorority house in Tallahassee the killer targeted; and Ruth, a guarded young woman struggling with familial and societal expectations, who has a fateful encounter with the killer a few years prior to the Florida murders.

Through their specific viewpoints, Knoll dissects the ways misogyny and male privilege enabled the killer to roam freely for years. But the violence is mostly off-page, allowing space to show both women achieving small but poignant victories in the shadow of devastating violence. Knoll was ready to answer our questions about her approach to the thorny source material.

Throughout the book, you avoid sensationalizing the scenes related to the murders, but you also don’t gloss over the grisly nature of the assaults.

Jessica Knoll: It’s actually something that I talked about with one of the survivors from the Florida attack—Kathy Kleiner, who was attacked that night, but survived. Her feeling is that people should bear witness to the horrors of it and that she doesn’t want people to turn away from it. Before I really even wrote a word, I reached out to Kathy. I wanted to speak to her and kind of have her blessing to move forward. Now, that’s not to say that I got that from everyone who was involved. But I did have a conversation with Kathy where I really connected to her, one survivor to another. I can see a kind of through-line with Luckiest Girl Alive, where my own experience with sexual assault was embedded in it.

Aside from not naming the killer, what other concerns did you have about portraying him?

I wanted to disprove the idea that he got his victims with his looks and charm. A lot of what we heard was that women trusted him because he was so good-looking and charming. But more often than not, he posed as injured and would solicit young women for help.

There’s an eyewitness account from the Lake Sammamish murders where he murdered two women in one day. There was a high school girl who was on a beach towel very close to the first victim who overheard and saw everything.

Her account says that the victim was very irritated with him. She felt like he was bothering her. She just was laying out on her towel trying to get a tan, trying to enjoy the day, and he came over and was just kind of ruining her day. She really had to be convinced to go off with him. He had his arm in a sling, and he said, “I was supposed to meet my friends down here and they were supposed to help me load sailboat at the back of my car, and I can’t find them.” And he was like, “Would you help me?” And she didn’t want to, but he wore her down. I thought, Wow, it’s such a different thing to go off with someone because you feel you can’t say no.

It’s the sort of patriarchal conditioning that people are talking about more and more.

I think of all the things that I’ve said yes to over the years that I didn’t want to say yes to, but I didn’t feel like I could say no. I'm better at saying no now, but it’s still really uncomfortable. I’m shaken for a day afterwards and I’m normally berating myself a little bit. So to think that it’s hard for me—in 2023, when we are having these important conversations about patriarchal conditioning and the caretaking role that women are expected have—what must have it have been like for a 21-year-old young woman in the 1970s? It kind of feels like they didn't have a chance. … I feel like right now, I’m focused on improving that within myself and getting more comfortable with being uncomfortable.

There are two main characters in this novel. Let’s start by talking about Pamela Schumacher. She’s a resourceful woman who is the president of her sorority house in Tallahassee where the killer strikes in 1978, and we follow her in the nerve-racking days after the attack. Her role as an eyewitness radically shifts her view of the world—of everything from the guy she’s dating to the media coverage of the crime. Can you talk a little bit about creating her voice?

She’s very much like a Tracy Flick character [from the 1999 movie Election, played by Reese Witherspoon]. Actually, in very early drafts, she was just a side character and the Florida years were told from the perspective of Cindy Young, who now only makes a small appearance as an art student who does the initial first sketch of him.

Pamela always featured in the story because she was the sorority president and she had all these notions about how they should behave in the wake of this terrible event. After several passes of my editor and my lit agent reading it, they came to me one day and they were like, “We want to propose something really radical: Pamela seems like the most interesting character and we would love to get more of her voice.” And so I started all over with those chapters.

She was just a lot of fun for me to write, even though a lot of what she’s dealing with is very dark. But I could see a lot of myself in her as someone who is very tightly controlled and any kind of disruption to her plans is intolerable to her. I wanted her to look inward when this [tragedy] happens—to ask herself why, and to self-actualize as a result of it. And I think that was something I was kind of doing on my own as well, so I feel like a real kinship toward her.

The other central character is Ruth Wachowski, a young lesbian woman who, in 1974, is fated to cross paths with the killer. She’s in a battle of wills with her mother, who forced Ruth into conversion therapy at age 17. How did you develop her story arc?

I did a lot of research around what the attitudes were toward queer people in the ’60s and ’70s. Homosexuality was still listed in the DSM as an illness when Ruth would have been a teenager. So back then, the attitude was that it was an illness and it could be cured.

I spent many hours speaking to Elyse Resch, who I saw for a couple of years for intuitive eating [counseling]. Elyse was a young woman in the ’70s who was married to a man, ultimately got divorced, and married a woman. I asked her what it was like to be with a woman in the ’70s, to share a house together. She was very generous with her experiences and her time. I don’t think I could have formulated the character of Ruth without her.

Why did you feel it was important for people to reevaluate the Defendant’s legacy?

I think it’s because of what happened to me when I was young, when I was assaulted. There was a narrative around that night in high school that it was just a party that got out of control. And it really embedded something in me where I was like, “No, we have to set the record straight.” And when I saw that a lot of what was written about [the killer] was so easy to disprove, I just felt irate on behalf of the women who were forgotten for this man, who has this kind of lore that isn’t even based in reality.

In my author’s note, I thank Pauline Boss, who came up with the idea of ambivalent loss. She wrote the book The Myth of Closure. It’s all about how we don’t ever really get closure for painful events in our life and that searching for it is the wrong thing to focus our energy on.

She’s seen that, clinically, what helps people heal and move on is the ability to find meaning in this terrible thing that happened to them. So if you can find meaning and feel some gratitude toward that, that’s how people can live well—as she says, live well with pain.

That really comes through in how we see Pamela’s character progress. She’s studying law when we first meet her. But we also see her in present day when she has become a very different kind of lawyer than her father. She ends up in mediation, which feels meaningful to her.

For Pamela, it was like: If this had never happened to me, I would’ve become a lawyer but it would’ve been passionless. Because of this [tragedy], I switched the area of practice that I wanted to be in, and I did something with my life that brings me fulfillment and joy and a sense of accomplishment.

That’s her purpose and meaning in life, and she never would’ve had that. I mean, it’s what I’ve found too. I wouldn’t have my writing career without what happened to me. I’m not grateful for what happened to me, but I can accept it because I found meaning in it. And that gives me peace.

Bright Young Women, Hardcover

a.co

$25.19

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You Might Also Like