Jennifer Homans Shines a Miner’s Light into the Secrets of “Mr. B”

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

With the advent of the holidays, dance fans surge into concert halls for an evergreen enchantment: Tchaikovsky’s The Nutcracker, capped off by a towering Christmas tree and the delicate pointe work of the Sugar Plum Fairy. George Balanchine, one of the 20th century’s magisterial choreographers, gravitated toward The Nutcracker just as surely as a toddler reaches for a toy; his vision remains a cornerstone of the New York City Ballet’s repertory to this day.

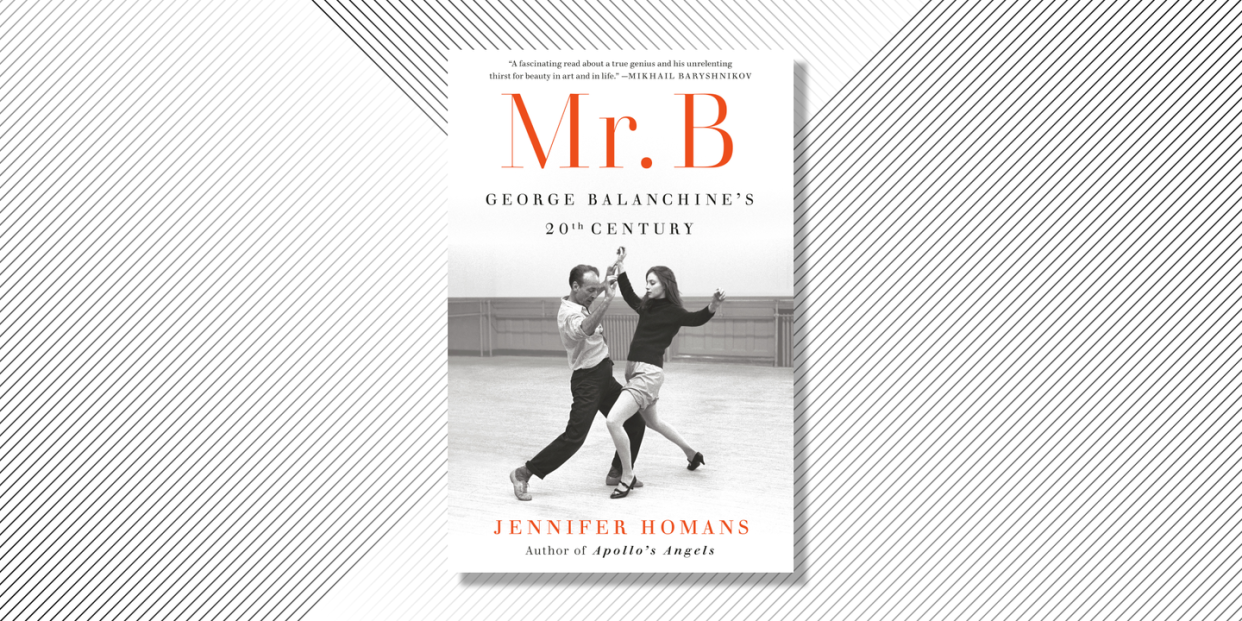

Balanchine’s childlike wonder and fleet-footed technique permeate Jennifer Homans’s elegant new biography, Mr. B, as she chronicles an odyssey from the blood-red sunset of czarist Russia to the hustle and hijinks of postwar New York. Homans, author of the celebrated Apollo’s Angels (2010), bores deep into her subject, shining a miner’s light into the shadowed crevices where the secrets hide. She comes away with a gorgeously written, intricate account, even as the master slips her gaze, elusive.

Born Georgiy Balanchidvadze in St. Petersburg, in 1904, he came of age in a moment of tumult and transition. His father, an accomplished composer, had been previously married in his native Georgia; his Russian mother steered her daughter and two sons toward artistic pursuits. After she won the state lottery (a statistical rarity), the family divided their time between a luxurious apartment and a country house in Finland. When his sister auditioned for the Imperial Ballet School, Balanchine tried out as well; he was selected, while she was passed over.

Homans sifts through a scarcity of archival material with élan. Once Balanchine was packed off to the rigors of boarding school, his ties to his family were largely severed. In Mr. B they remain distant and blurred, but integral to his formation as an artist; he kept a photograph of his father next to his bed throughout his life. In the aftermath of World War II, St. Petersburg was carved into pieces by Bolshevik revolutionaries and renamed Leningrad. As a teenager, Balanchine dodged bullets and foraged for rats before fleeing to Paris, where he joined Diaghilev’s émigré Ballet Russes as both dancer and instructor, marrying the first of his four wives and absorbing—then transcending—the vocabulary of classical movement. He wrested the steps to his own ends. Homans suggests Balanchine was always more invested in creating dances than in seeking the limelight himself. His decade in Europe launched a trajectory that brought him to the United States in 1933, the beachhead for his future company. Here Homans finds her footing. Her portrait of the choreographer’s business partner, Lincoln Kirstein—a Jew and closeted homosexual ensconced in the Northeastern WASP establishment—is rich and resonant; Balanchine would have been unthinkable without Kirstein’s unflagging support.

Amid his ballets, Balanchine migrated between coasts, raking in commissions from popular entertainment. Homans succinctly summarizes his philosophy: “Simple songs to simple music: this is what he liked about Broadway and Hollywood. It was direct, clever, clear, no pretense, and he had serious and enduring admiration for Rodgers and Hart, the Gershwins, and Cole Porter. Their workmanlike approach was his approach too: just work, no drama, no fuss. For a man who drew from such deep emotional wells, he had remarkably little angst in the studio. There, he was unencumbered.” He blended this method with explorations of Greek myths and abstract expressionism, opening the door to fresh insights and innovation. Not for him the treacly Russian forms.

With the founding of the NYCB, Balanchine hit his stride just as America flowered among the rubble of Western cultures. “The early 1950s brought an outpouring of new dances, and the range from light to dark, from pleasure to beauty and pain, was impressive,” Homans writes. “We can see the NYCB repertory already had everything: founding texts like Serenade, Apollo, Concerto, Barocco, The Four Temperaments, and Symphony in C…Firebird and Swan Lake and (soon) The Nutcracker.” The NYCB toured frequently, at home and abroad, even accepting an invitation to the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War. Balanchine’s politics were conservative and pro-capitalist, although he occasionally ran up against the walls of made-in-America institutions. In one pas de deux, he paired Arthur Mitchell, a Black male dancer, with a white woman, Diana Adams, risking a public outcry. But as Homans notes, “George said nothing; he just did it.”

Balanchine was nothing if not a woman’s man. He was endlessly falling in love with his ballerinas—sometimes two or three at one. He occasionally married his muses, from the Norwegian Verna Zorina (née Brigitta Hartwig) to Native American Maria Tallchief (a desultory relationship) to the fiery French American Tanaquil “Tanny” LeClercq, disabled by polio in her prime. He channeled his passion for his performers into the works he made for them, such as the groundbreaking Agon (1957), set to music composed by Stravinsky. “Agon is a woman’s world,” Homans observes. “The four men open and close the performance and have the first and last breath, but the eight women dominate: they are confident, even aggressive, and with the notable exception of the pas de deux, barely in need of male support…they are the source of the ballet’s primal energy and self-assurance and of its humble grace. They are on pointe, but their toe shoes are not used to emphasize the ethereal and are instead made to dart into the floor, propel the body, mark time, extend the leg not up but down into the ground, weight slung low, or precariously suspended. They are instruments of mathematical precision, of logic and calculation.”

For devotees of Apollo’s Angels, the magic is back, as Homans brings us into the sweat and strut of studio classes, the jumps and jolts of business deals, the hushed thrill of Manhattan theaters. Mr. B pirouettes and arabesques in clean lines, even though it occasionally wobbles. (Homans lavishes attention on “lavish,” for example; I counted at least a dozen instances in the first half of the book.) She struggles with unlocking her protagonist—he’s somehow too light on his feet—but she leavens the biography with wry anecdotes and a command of ballet. Balanchine may have been a genius on an Olympian scale, but in Mr. B, he’s relentlessly, allusively human.

You Might Also Like