Jelly Roll’s Journey From Juvenile Hell to Country Gold

This week, in the latest installment of our Change Is Good initiative, GQ editions around the world are spotlighting people who embody positive transformation. This story comes from GQ US.

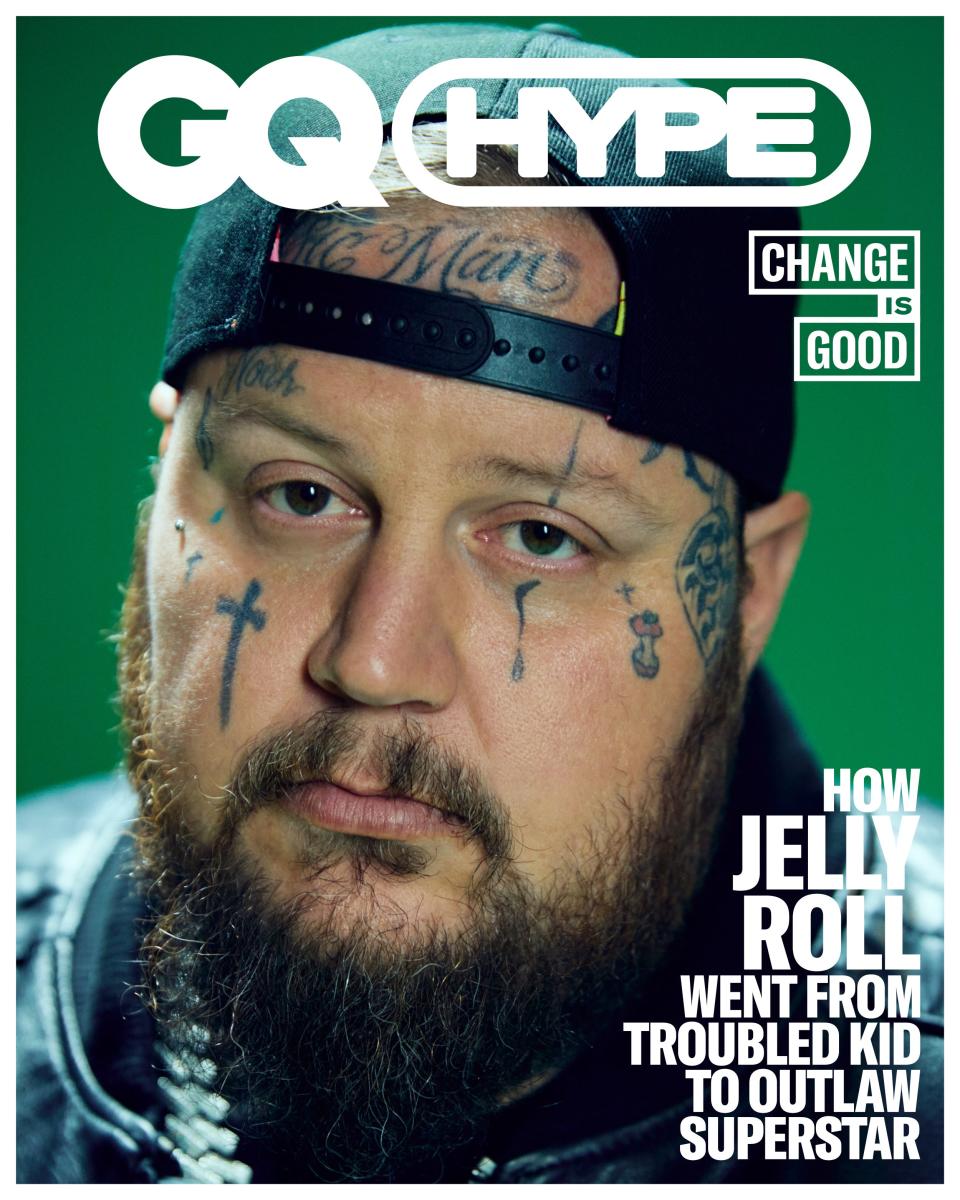

When I click the YouTube link, what comes up first is an ad. It’s a commercial for the Beautifully Broken Tour, which will take Jelly Roll—the husky, 39-year-old Nashville native who has belatedly become one of the biggest stars in country music, and indeed all of pop—across America this summer and fall, from Madison Square Garden in New York to LA’s Crypto.com Arena. Ticket presale information plays over footage of Jelly Roll performing with his band, belting the choruses from his quartet of recent Top 40 hits. Even with stage pyrotechnics exploding behind him, he commands the frame, his scraggly beard hanging down, his face punctuated by at least a half-dozen tattoos. But when the ad’s 15 seconds are up, this Jelly Roll disappears.

Taking the superstar’s place on my screen is the Jelly Roll of more than a decade ago: clean-shaven save for the hint of a goatee, his buzzed hair dressed up with a slight fade, rapping with a few buddies in what looks like a corner of somebody’s living room. The “10 Minute Freestyle” is named for the time constraints YouTube once had on uploads; the full session was much longer. “We were cyphering all day,” Jelly tells me when we meet on a rainy afternoon at the BMG offices in Nashville. While it’s impossible to say how many times this footage has been seen—the original upload amassed millions of views before it was yanked down at the insistence of the parole board to which the man born Jason DeFord was once accountable—the charisma its subject exudes is beyond quantification. “I still get money/Yes, I ball,” he raps, pointing to his chest as if he’s wearing a platinum chain and not what he now calls a “goofy-ass” brown polo shirt. “And if my PO asks, I hang drywall.” The punchline elicits such a reaction in the room that it knocks the cypher offbeat.

You would not mistake these two Jelly Rolls for different men. There’s a consistency in how he draws out his vowels, the contortions he makes with his face, the miniscule rhythmic adjustments he makes to ensure the end of each line snaps like a rubber band. As he sits in the BMG building, enjoying a precious bit of downtime between the chaos of Grammys week in LA and a string of festival and tour dates that will take him all the way to Halloween, Jelly is far removed from the gregarious rapper whose polo shirt was, in fact, evidence that he’d arrived straight from his PO’s office. But the years spent honing his creative and commercial instincts on the Southern-rap mixtape circuit—and the time he spent in an array of correctional facilities, dating back to his teenage years—are the basis of Jelly Roll’s seemingly newfound success.

And some success it’s been. Over the past year, Jelly’s been nominated for new artist of the year at the Country Music Association Awards, which he won, and best new artist at the Grammys, which he lost to Victoria Monét. The Grammy category has long fueled jokes about how late the Recording Academy is to pick up on emerging acts. But Jelly Roll’s nomination did capture a certain truth: While he’s been releasing music since George W. Bush’s first term, his recent run represents the end result of a reinvention and rejuvenation that goes beyond even the obvious pivot from hip-hop to country.

The past half-decade or so has been a time of personal as well as professional transformation for Jelly Roll. Where he once trafficked certain drugs and rapped about his proclivity for others, he earlier this year testified before a Senate committee about the fentanyl crisis; a juvenile facility in which he was locked up is now outfitted with a recording studio he funded. And to produce the hits that have precipitated this fame and fortune, Jelly had to for the first time welcome others into what had previously been a hermetic creative process.

“I lived on an island,” he says. “I was such a singer-songwriter I didn’t have the proper respect for the writing community—I maybe had a sneered nose to ’em.” He got over his distaste, found collaborators he trusts, and has become one of the truest breakout stars of the 2020s; last year’s Whitsitt Chapel earned rave reviews from country critics, the number three slot on the Billboard 200, and this raft of awards nominations.

And yet he’s not ready to completely cede control of his process. After he lavishes praise on the “writing community”—the pro songwriters who’ve propped up Nashville’s recording industry for decades—he offers some important caveats. “I don’t want nobody in the room to ever dictate what I say,” he insists—not because of ego, or style, or publishing splits, but “because they’re not accountable for it.” For as gracious as Jelly Roll is to hundreds of employees on every floor of this building (later, upstairs, someone recounts his showing up with a bag of Rolexes for the radio team), he knows whose name is on the spine of the LPs. “I’m accountable for these words,” he says. “I’ve gotta stand on them.”

Jelly Roll grew up the youngest of four children in Antioch, a “very rural” neighborhood southeast of Nashville. He describes it as racially diverse and straddling the line between middle- and lower-class, though it sounds more like the latter when he adds, “I don’t think I knew anybody with a real job.” (Later, with a laugh: “I didn’t even know a barber.”) His father was a meat salesman and a bookie, and when Jelly was a preteen, he used to earn an allowance by waking up early on Sunday to score betting slips from the day before. “ESPN didn’t run what happened between Alcorn State and Northwestern,” he says. “If you wanted to know what happened between Bowling Green and whoever, I was the guy.”

In those days, he says, “I just remember everybody doing drugs. I was in my 20s before I realized that having a drug addict in your family wasn’t normal.” As the 1980s became the ’90s and then the 2000s, the specifics of the addictions in his community have changed, even if their repercussions haven’t. “I’ve lived long enough to see crack, opioids, and fentanyl,” Jelly explains. “They’re very similar in texture.” Like a handful of his neighbors, he found his way into the cocaine business, though that was hardly a windfall. “It was scratching and clawing by,” he says, “and sadly, scratching and clawing by was better than everybody else. I don’t remember nobody with real money.”

In front of that Senate committee, after noting that the number of people who die of overdoses in America each day would fill a 737 jet to capacity, Jelly said that he’s “attended more funerals than I care to share with y’all.” Indeed, nearly every American’s life has been touched by addiction. So while Antioch seemed—and in many ways, was—uniquely squeezed by the socioeconomics of late-20th century America, one thing Jelly has come to realize since his step into superstardom is that his hometown isn’t so out of the ordinary.

When he was being filmed for the documentary Jelly Roll: Save Me, an ABC News employee said, “Oh, I get this: There’s a little town like this everywhere in America.” Initially Jelly bristled at the comment. But the more he thought about it—and the more widely he has toured—the more he realized she was right. “Antioch is every blue-collar neighborhood in America, to some degree,” he says. “It’s the west side of Columbus, it’s the south side of Indianapolis.” Jelly suggests that this fact—and his awareness of it—is one of the reasons his songs so easily cut across regional and racial divides.

Jelly got tangled in the penal system to a degree that was unique even among his peers in Antioch. Beginning when he was a teenager, he cycled in and out of lockup on a variety of offenses. While it’s impossible to put a positive spin on the corrosive psychological effects of incarceration, it had one practical benefit: He finally had time to write.

As a kid, Jelly had learned to be a musical omnivore, cherry-picking bits of his parents’ and siblings’ taste. (He and his mother used to sit at the kitchen table and cry to Bette Midler’s “The Rose”; one Christmas, his brothers pitched in to buy him a cassette of Wreckx-N-Effect’s “Rump Shaker.”) But by the time he was doing stints in juvie, he was committed to rap. Inspired by Southern staples of the time—the Geto Boys, 8Ball & MJG, fellow Tennesseans Three 6 Mafia—he would spend his time behind bars beating drum patterns into tables until they would play on loop in his head, then fill up reams of paper, sharpening his verses and shaping them into full songs, with choruses and long arcs. At the same time, he was developing a reputation as a freestyler, but this was something different. “Nobody knew me for writing,” he says. “But every time I got incarcerated, I would go do a year, year and a half, and I would just write.”

It was during this time that Jelly had his first actual brush with rap success. He was 15, and had just received his first weekend pass out of a juvenile facility cocooned in razor wire. One of his friends invited him to go to a car show in nearby Lebanon where his cousin, the Nashville rapper Haystak, would be performing. “For the first time in my life, I’m in the room with somebody with a big chain, a Rolex, he’s dressed cool as shit, everybody’s saying ‘What’s up’ to him, girls are flashing him on cars. It’s wild!” Jelly remembers. “He was like, ‘You’re the kid who’s locked up—spit something,’ because he was incarcerated as a youth. So I spit something right there on the spot. And he was like, ‘Man, you’ve got something. You just gotta stay out of trouble.’

“Which,” he adds, “I didn’t.”

Jelly continued to build momentum as a rapper; he and Haystak even became close collaborators. But something wasn’t right. Jelly’s singles, like “Pop Another Pill” and “Welcome to the Trap House,” were “misleading,” he says. The tracks that showed audiences “the depths of who I was” were usually deep cuts buried on his albums. But when he started selling a couple hundred tickets at a time to shows around the South, he noticed that his more contemplative songs actually got a bigger audience response. He then began to notice his writing drifting farther in this direction, too: He would record dozens of songs for an album just to realize that only a few were over 65 beats per minute.

“My soul is to write ballads—that’s what pours out of me, dude,” he says. Today he speaks about the creative process as a mixture of science and alchemy, dissecting structure with a cool detachment while remaining raw to a song’s emotional underpinnings. “It’s still precious to me,” he says. “I kind of enjoy feeling that way; I’m still glad I get real palm-sweaty before interviews, get real nervous before shows. I love that. I’m still here for the right reasons.”

There is likely a contingent of people who have never heard a Jelly Roll song but have nevertheless come to admire him. They have maybe seen and been touched by his Senate testimony, or the video of him crying as he calls his mother to tell her he was nominated for two Grammys, or his moving best new artist acceptance speech at last year’s CMAs. “There is something poetic about a 39-year-old man winning new artist of the year,” he said then, hunched over a microphone set far too low for him. “I don’t know where you’re at in your life or what you’re going through,” he continued, his pace quickening, voice beginning to tremble like a preacher’s. “But I want to tell you to keep going. I wanna tell you success is on the other side of it. I wanna tell you it’s gonna be OK. I want to tell you that the windshield is better than the rearview for a reason.” Online, some Jelly fans have added church-organ stabs to the audio of Jelly’s speech, but it feels like a sermon even without them.

Jelly has not always exuded this sort of confidence. While his introduction to Haystak, he says, kept him focused on music during his young adulthood, he later reached an emotional low point, until a far bigger celebrity began showing love. “I was first moved by his music in 2017,” the actor Dwayne “The Rock” Johnson tells me. “I was going through a rough patch at that time, dealing with stuff on the personal side. I was doing my best not to let anybody know.” After Johnson posted one of Jelly Roll’s songs to his Instagram, the pair struck up a correspondence that continues to this day. “I told him recently: ‘DJ, you don’t know this, but there were so many times that your friendship alone was my anchor,’” Jelly says. “I was like, There’s no way one of the most famous people on earth is seeing something that everybody else can’t.”

There were no acceptance speeches at the Grammys, where Jelly also lost best country duo/group performance to Zach Bryan and Kacey Musgraves. But he was pleased with how he was received. “My barometer is more the people working there: the security, the bartenders,” he says. (A friend who’s worked at the Crypto.com Arena since it was the Staples Center confirmed Jelly’s man-of-the-people status in a text: “everybody fucks w jelly roll.”) When he wins industry awards, Jelly says, he’s always surprised that his appeal has trickled upward. “It’s like, damn, I didn’t even know y’all were seeing what I was doing,” he says. “I knew the cook was seeing it, because he shouts at me every time I go to the steakhouse. I knew the valet parker was. But was the dude running ASCAP seeing it?”

Now Jelly is focused on reaching beyond those blue- and white-collar workers and speaking to the kids whose circumstances are as dire as his once were. The juvenile facility where he spent his 15th, 16th and 17th birthdays now offers writing workshops to its residents; each cell block has its own workshop, to avoid violent confrontations. Jelly’s goal, he says, is to one day write a hit song with one of the young incarcerated people who are housed there. “If I had seen an example of success,” Jelly says, or if he’d had access to a studio on the inside, “I’d be light-years ahead of where I am.” The last time he visited the facility, he says, he went through a “Who’s on First?” routine with a kid who’s incarcerated there.

Why are you here? he asked Jelly.

“’Cause I was here.”

You were in a group home?

“No, I was here.”

In the system?

“In this facility. In this jail. In this kitchen we’re sitting in right now.”

You were here?

“I was in Bravo—what they call Bulldog now. I was here longer than anybody in history at one point.”

Did you make some money?

“Yeah.”

Real money?

“Tens of millions of dollars.”

And you were here?

“Motherfucker, if you ask me that one more time…”

PRODUCTION CREDITS:

Photographs by Aijani Payne

Grooming by Lindsay Doyle using Jaxon Lane Skincare

This story was featured in The Must Read, a newsletter in which our editors recommend one can’t-miss GQ story every weekday. Sign up here to get it in your inbox.

Originally Appeared on GQ