How Jeff Koons Built the Art World’s Most Expensive Shrine to Middle-Class Taste

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

The world’s most expensive living artist is slowly making his way across an elegant Florentine square. Photographers surround Jeff Koons like a flock of hungry seagulls. It is the launch of his first big retrospective in Italy and he’s getting the kind of attention normally reserved for a Hollywood film star. Koons, 66, is one of a handful of celebrities in the world of visual art whose name pulls crowds to museums. He is also one of its most divisive figures, whose sculptures sell to the super-rich for tens of millions of dollars.

Over the past 25 years the growing number of high-net-worth individuals has led to an explosion in the contemporary art market. According to Artprice.com, the contemporary art price index soared to an all-time high at the beginning of summer 2021—with price increases of 400 percent since the early 2000s. In the past year alone, $2.7 billion worth of contemporary works have changed hands at auction. About a third of these sales are generated by a handful of artists: Koons is one of them, Banksy is another. In 2019 Koons became the highest-selling living artist when his stainless-steel Rabbit, modeled on a child’s inflatable bunny, sold for more than $91 million to a billionaire hedge fund manager.

More from Robb Report

How Nature, Climate and the Refugee Crisis Inspired Artist Michal Rovner's New Works

One of Banksy's Most Famous Paintings Will Be Sold as 10,000 NFTs--for $1,500 Each

The Met Just Got a $125 Million Grant, the Largest Donation in Its History

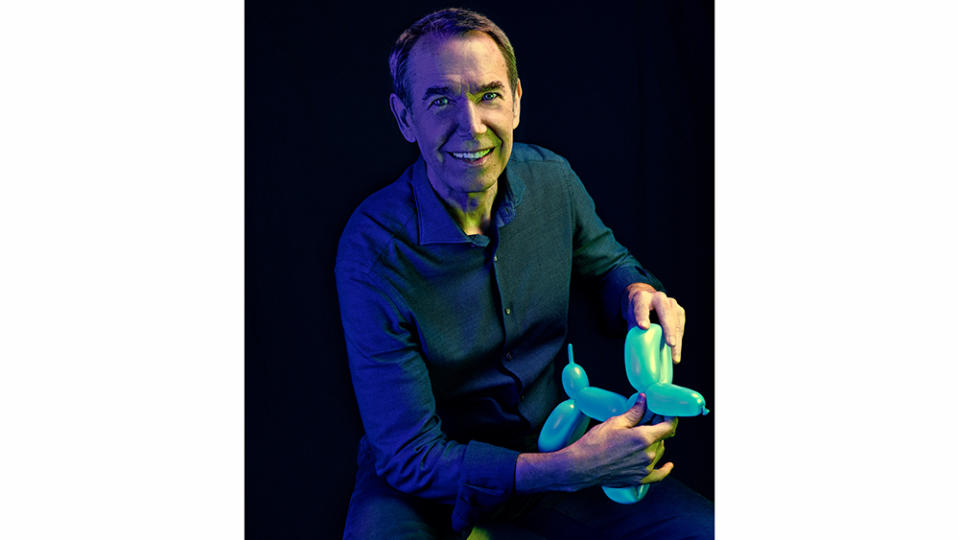

Slim with a well-coiffed head of dark hair, Koons is dressed in a navy shirt and a well-pressed pair of jeans. He looks more like a Wall Street banker than a tortured, paint-splattered creative—perhaps because he once was. He spent six years as a commodities trader before taking up art full-time. Today, his work divides the art world between those who think he is a cynical salesman creating big, shiny, superficial trophies and those who see him as a great figure in the American pop art tradition, the heir to Andy Warhol.

For Koons to be exhibited in the home of the Renaissance is an important affirmation. He may have conquered the market since he emerged from the New York art scene of the 1980s but he has struggled to conquer the critics. In 2004 the renowned Australian art critic Robert Hughes famously wrote: “Koons really does think he’s Michelangelo and is not shy to say so. . .He has the slimy assurance. . .of a blow-dried Baptist selling swamp acres in Florida.” But attitudes towards him are shifting and many world-class museums have exhibited Koons shows in recent years, including the Ashmolean in Oxford.

Koons’s manner is patient and polite with everyone who approaches him. When I first meet him in Florence he nervously asks me if his breath smells. Apparently there had been some confusion over his breakfast order. “I asked for an egg-white omelette with onions, spinach and tomatoes and after eating it I realized they’d put garlic in, so if you can smell something, please tell me.” He is a perfectionist who likes to be in control of his environment. The unexpected garlic has clearly thrown him.

Like his artworks, he is polished on the outside, but the carapace is difficult to penetrate. He often seems to be talking from a pre-written script, with stock phrases that are constantly repeated. Talking to him can be a surreal experience as he robotically trots out a ready-made narrative about his art and his life, regardless of the question posed. When I ask how it feels to be exhibiting in Florence, he says he’s “thrilled to be involved in a dialogue with a wider community about art. I’m thrilled because when I started, I knew nothing about art.” He then launches into a well-rehearsed story that appears in almost every interview he’s ever given about growing up in suburban Pennsylvania. It’s an origin story that is deeply rooted in a bright and hopeful postwar American consumer culture—and a theme he will return to repeatedly during both my encounters with him, first in Italy and later at his studio in New York.

Born in Pennsylvania in 1955, Koons was encouraged to take art lessons by his parents. “I remember around the age of three, I made a drawing and my parents gave me lots of praise. My older sister Karen could always do things better, [whereas] art was something I was good at.”

He says he learnt aesthetics from his father, who was an interior decorator at a furniture store. As a boy, Koons reveled in the constantly changing window displays in his dad’s store. He made copies of famous artworks, which his father displayed and sold—an important early validation.

In 1972, the 17-year-old Koons left home to attend the Maryland Institute College of Art in Baltimore. At first he felt like a fish out of water. Or as he puts it: “I survived art school because I was able to accept my own cultural history. I grew up in Pennsylvania in a middle-class background. I was able to accept who I was and see that if something had meaning to me, I could communicate that to other people through my art.” The references to “self-acceptance” are another recurring theme in the Koons script.

He moved to New York after graduating and got a job working at the membership desk of the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), where he quickly gained a reputation for his impressive sales patter. His next move was to Wall Street, where he worked as a broker selling cotton futures over the phone. It was the 1980s, an era associated with yuppies and greed. It’s part of the mythology around Koons that his Wall Street background has somehow been instrumental in his success. But this is something the artist himself disputes, insisting that selling commodities was nothing more than a day job. He did it to fund his art.

On the Tate website, Koons is described as an artist who “uses unlikely subjects to poke fun at comfortable suburban lives and tastes, and criticize a contemporary culture driven by commerce”. But he says: “My work is not about consumerism. I’m not making a comment on consumerism.” In the Koons world there is no hierarchy of objects. “I tend to work with images that can be looked down upon, but you have to accept your past and who you are.” Koons is not criticizing suburban taste, he is putting it on a pedestal.

Working with “images that can be looked down upon” is central to his practice—whether it’s inflatable pool toys, balloons, garden gnomes, gift-shop souvenirs or household appliances including vacuum cleaners, pots and pans and pressure cookers. His role model is the French artist Marcel Duchamp, who coined the phrase “readymade” to describe mass-produced objects that he designated as art. Critics often describe Koons’s work as kitsch, a word he hates because it’s judgmental.

He explains to me at length how being non-judgmental is central to his personal philosophy of self-acceptance. “The more you can remove judgment and practice acceptance, the more you are open to everything that exists in the world. Judgment leads to anxiety and segregation,” he tells me with a Zen-like smile. To start with I’m not sure whether he believes his own patter, but after spending a couple of days with him, I conclude that he does.

Guerin Blask

Most of Koons’s sculptures come in multiples—there are four editions of the famous stainless-steel Rabbit, one of which is making an appearance in Florence. They’re known for being technically very difficult to produce. Every seam and crinkle on the plastic toy from which it is created has been replicated in steel. But instead of being cute or childlike, there is something sinister about its dagger-shaped ears and lack of facial features. When I stand in front of it, a warped version of my reflection looks back at me like the distortion in a funfair mirror. It’s quite unsettling.

Alexander Sturgis, director of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, believes that Koons’s works must be seen in person to be appreciated. “It’s their physical presence—the lunatic care and attention is tangibly there when you are in front of them. Some of his surfaces are unlike anything you encounter anywhere in the world, super-shiny, colored reflective surfaces that are almost liquid.”

It seems appropriate that Koons’s latest exhibition should be housed in the 15th-century Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, which was built by wealthy bankers at the height of the Renaissance. According to the show’s curator, the art historian Arturo Galansino, the Strozzi family were big collectors, comparable to the New York hedge funders who collect Koons today. “The Strozzi were the richest men in the world, who liked to spend huge amounts of money on art to show how rich they were. Art history was invented here and Koons belongs to art history,” he says.

The Palazzo Strozzi, like all museums and galleries, is reeling from the financial blow of the pandemic. The hope is that Koons’s sculptures will pull in the punters. His shows are popular with families because youngsters respond to the childlike aspect of his work. And then there’s the Instagram crowd. On the day of the opening I watch a group of young women pose for selfies in the reflective mirrored surface of Koons’s monumental stainless steel Balloon Monkey. The electric blue sculpture modeled on party balloons fills the inner courtyard with its long phallic tail. There’s something deliberately sexual about it.

Koons has a strong personal connection to Italy, but it’s a painful one. His oldest son, Ludwig, from whom he was estranged for many years, is Italian. His first wife, Ilona Staller, was a Hungarian-born Italian porn star, who was briefly an MP in the 1980s. Known as La Cicciolina, she had a novel approach to international diplomacy: She once offered to have sex with Saddam Hussein in exchange for letting weapons inspectors into Iraq. Koons met Staller in a nightclub and initially hired her as a model for a series of very graphic sexual paintings and sculptures depicting the pair of them in various positions of the Kama Sutra. He called the series Made in Heaven and said he hoped it would neutralize “shame around sex.” Instead it caused outrage in the art world, cementing Koons’s reputation as a cynical self-publicist. The couple married in 1991 but three years later, after their son was born, had an acrimonious divorce and a long, bitter custody battle.

It’s hard to reconcile the mild-mannered man I meet with the exhibitionist who once posed naked, simulating sex with a porn star. He comes across as a family man who is happiest when talking about his kids. He has eight in total, ranging in age from nine to 46. The oldest, Shannon Rodgers, was conceived while Koons was an art student. He wanted to marry her mother but she felt they were too young, and the baby was put up for adoption. Koons was thrilled when Shannon tracked him down in 1995. He’s in regular contact with her and his two grandchildren. His six youngest children are with his current wife, Justine Wheeler, a South African-born artist who once worked as his studio assistant and has proved to be a great stabilizing influence after the chaos of the Cicciolina years.

The custody battle over his son cast a long shadow. When Ludwig was a toddler, he was taken by his mother back to Rome in contravention of a New York court order and didn’t see his father for a long time. Koons told The Guardian that Ludwig “was turned against me” and that the legal costs nearly drove him to bankruptcy. During that time Koons destroyed some of the Made in Heaven series. There was some speculation that he had done this in anger, but he is also reported as saying he did it to protect his son after his ex-wife claimed the works were pornographic. It was clearly a very painful period for the artist who set up the Koons Family Institute on International Law and Policy to help other parents in similar situations. Though I am asked not to bring up the saga, I am assured that he and Ludwig, now 29, are on good terms.

He gushes with pride when I ask if any of his children are artistic, telling me that one of his two daughters, Scarlet, wants to be an actress and a stand-up comedian, and his youngest son is extremely gifted at drawing. “Probably the greatest pleasure I have is showing my children a way in the world in which they can flourish,” he says, smiling. “We drag them round museums all over the world. We usually spend new year in a foreign city and that would involve a visit to a gallery or museum. They would be with me here in Florence if it wasn’t for school.”

The Koons family split their time between a townhouse on the Upper East Side of Manhattan and a farm in Pennsylvania. Eighteen years ago he and Justine decided they wanted the children to experience rural life, so went house-hunting in Pennsylvania. After looking “at literally hundreds of places” they ended up buying his grandfather’s old farm, which had been sold when the artist was four years old. “We knocked on the door, I explained about my grandfather, so they invited us in, showed us round and you know what? About three months later they rang and said, ‘Would you be interested in buying?’ ”

Less than a week after meeting Koons in Florence I visited his studio in New York, where he designs his artworks with the help of about 50 assistants. He is renowned for working with cutting-edge technology and top craftspeople. When I ask if he makes anything with his own hands he answers, “Does the film director make the film?” His studio is two floors of an ordinary-looking office block in midtown Manhattan. Inside it looks more like an architect’s office, filled with rows of desks. There are mock-up models of his current shows in Italy and Qatar (which opens today), with miniature cutouts of the work in cardboard. The assistants sit in front of computer screens working on 3-D scans of his latest designs, known as The Porcelain Series, which will go on sale in about two years’ time.

When I ask Koons to explain his practice step by step, he ushers me into a small storeroom. Inside a tall gunmetal cupboard are dozens of small, garishly painted porcelain figurines: ballerinas with lace tutus and shepherdesses cuddling lambs. They remind me of the kind of thing my grandmother kept on her mantelpiece. “I’m always searching for stuff, you know, looking on eBay and in airport gift shops.” He riffles around in the back before excitedly pulling out a 1950s china ashtray. “I love this. My grandparents had one. They were made in Japan after the war.” It’s a blonde woman in a bathtub with her legs raised in the air. “Look, you can move her legs back and forth and she’s holding a fan over her breast—it’s very…” He searches for the right word before settling on “sensual”.

And once he has chosen an object, what’s the next step? Instead of answering, he starts telling me about his childhood again. “I grew up in Pennsylvania, in a middle-class family, my father was an interior designer. . .” I know the script now word for word. “I don’t want my art to be intimidating. Some people like to exercise power by feeling superior to others.” Eventually he explains how he uses technology to capture every detail. “I do CT scans, white light and blue light scanning until I have every measurement. We merge these different scans, take extensive photographs of the surfaces. . .”

Courtesy of Christie's

The Koons studio is effectively engaged in reverse engineering. Although he does make some changes—altering colors or small details—authentic likeness is important. Some of the sculptures will be cast in stone, some in metal in specialist foundries in Germany and the US. They can take years to make. But one of the hazards of this kind of work is being sued for copyright infringement. Koons has faced lawsuits where he was found guilty of this. Part of his defense was the sculptures were “made with the intention to parody”, which strikes me as a contradiction, given that Koons says his work is “not a comment on consumerism.”

The longest he ever took to make a sculpture was 20 years. Described by a Christie’s catalogue as a “meticulous, epic recreation of a child’s toy,” Play-Doh was inspired by a multicolored creation presented to him by his son Ludwig when he was a toddler. The illusion is perfect, it looks soft and organic; you want to touch it and squeeze it in your hands, but it is rock hard and made of aluminium. There are five in existence. In May 2018 Christie’s sold one in New York for $22.8 million. Damien Hirst—who has been a fan since his student days—has one in his large collection of Koons’s work.

But the lengthy production times have been an issue. Gagosian gallery, which represented Koons until last year, found themselves faced with lawsuits from a hedge funder and a Hollywood film producer, who ordered artworks from a sketch and then got impatient when several years later they still hadn’t been delivered. One of the buyers even tried to sell his before he got it. Buying Koons became a futures game. When I ask him about this, he says: “If you look at the history of making things, this is not unusual. Michelangelo took years to make his pieces. Remember how the Pope got impatient with him [over the Sistine Chapel]?”.

The artworks at the center of the lawsuits were his Balloon Venuses, colossal stainless-steel sculptures inspired by tiny fertility symbols dating back to the Stone Age. When I ask why they took so long to make, Koons explains that he recreated the shape of the palaeolithic object using party balloons, but it took him months working with a balloon artist to come up with the perfect model. Then they were stalled for another year while they waited for space in a specialist foundry to do the milling, the machining, the polishing and the painting.

“The idea that Koons is commercially successful needs examining,” Sturgis says. “He spends unbelievable amounts of money developing his artworks and has almost gone bankrupt several times. If he was interested only in making money, he could have made a lot more.”

Koons now has a new gallery, Pace, in downtown Manhattan. It’s a huge, eight-story space with white walls and pale wood floors, staffed by elegant young women dressed in black and white. One of the sales representatives explains to me that under their new regime “we will help facilitate production” and “no invoice will be issued until the work is finished.”

Georgina Adam, author of Dark Side of the Boom: the Excesses of the Art Market in the 21st Century, says: “Koons’s monumental sculptures are trophy works. If you own a Balloon Dog or the Rabbit you are among a select few. If you have a megafortune, there are few things you can spend your money on that other people cannot. These sculptures are made very slowly, very carefully for the super-rich, a bit like the way Fabergé eggs were made in the past.”

Koons has also indulged in what is known as “brand stretching” in the luxury goods market, Adam explains: “You can buy a Koons porcelain plate just as you can purchase a Picasso ceramic.” Then there are collaborations with the luxury goods industry on, for example, Louis Vuitton handbags.

In 2017, Jay-Z performed in Britain at the Virgin V Festival in front of a 40-foot inflatable Koons balloon dog, resulting in huge coverage for the artist on social media. And in the song Picasso Baby, Jay-Z raps: “Oh what a feeling, f*** it I want a billion Jeff Koons balloons.” Apart from Banksy, it’s difficult to think of another contemporary artist who has entered the bloodstream of popular culture in quite the same way.

Koons’s latest collaboration is with BMW. They asked him to make a special edition of the 8 Series Gran Coupé. “I have a large family. I’m used to driving around in a van that can seat 11, but this is something I’ve designed for myself.” He’s looking forward to unveiling it at the Frieze Art Fair in Los Angeles next year. “I feel like a peacock when I drive it. I want people to look and say, ‘Wow!’ But I also want them to see the presence of meaning and history.” That statement might work for his collectors and BMW buyers, but I’m not sure what the art critics will make of it.

Jeff Koons: Shine is at the Palazzo Strozzi, Florence, until January 30, 2022; visit palazzostrozzi.org. Jeff Koons: Lost in America is at the Qatar Museums Gallery—Al Riwaq, Doha, until March 31

Best of Robb Report

Sign up for Robb Report's Newsletter. For the latest news, follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram.