The “Japanese Goodbye” Ritual That Brings Me So Much Joy

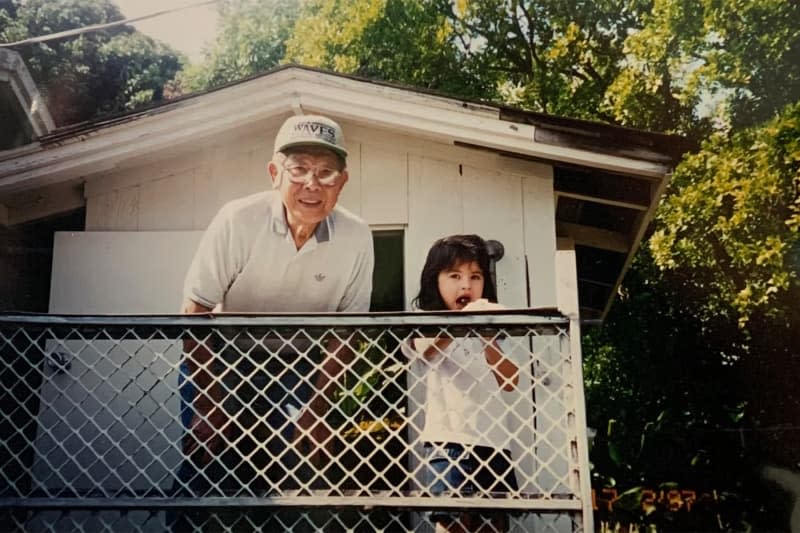

The last time I said goodbye to my great-grandpa was the same as every other time: He stood at the bottom of his steep driveway in northern Oahu in his rubber slippers and ball cap, waving and smiling until we couldn’t see him anymore. “Japanese goodbye,” my mom would joke, and we would laugh, because our Japanese family members were the only people we knew who always did this. While we always waved our own visitors out of sight, we usually stayed on our front step.

But even at 98, my great-grandpa walked all the way down to his driveway with us so he could properly say goodbye.

This family ritual has been passed across oceans and generations, all the way down to me, a fifth-generation Japanese American (or gosei). I’ve always offered and received this long goodbye as a gesture of care and respect for my guests, and I recognize when they do the same for me. At home in California, my family maintained the tradition just as faithfully on cold nights as on summer evenings. In Hawaii, all of my grandparents stayed firmly planted and waved hard to ensure our last glimpse of them would be their faces, not their backs.

I started to notice the difference this tradition made when I visited other homes and had the door closed promptly behind me, but I didn’t realize the ritual extended far beyond my family until my mother sent me an Instagram Reel about the “Japanese goodbye,” with endearing clip after clip of Japanese people giving the same extended farewell.

Michael Yuge, executive director of the Tenri Cultural Institute in New York, shares a similar journey of realization. Yuge is a third-generation Japanese American (or sansei) who grew up in Los Angeles and taught English in Japan; he says that when he was growing up, his family always walked their guests to the driveway gate.

“It was common courtesy for us to open and close the fence for them,” he says. “I assumed that was just a part of our family’s culture. But we are also a part of Tenrikyo, which is a religion from the Japanese city of Tenri. And in our churches, we commonly see people out until we literally can’t see them any longer. That was part of our religious culture, but in retrospect, it’s also just a part of Japanese culture.”

The extended farewell is tied to the broader Japanese cultural attitude towards hospitality, Yuge says. “My wife, who’s from Japan, also pointed out that it is part of the Japanese culture of omotenashi — the attitude of what it is to wholeheartedly look after guests. Properly inviting and seeing off guests is a part of this.”

Today, Yuge maintains the “Japanese goodbye,” waving guests away from his New York home until they are out of sight. I do the same, whether I’m walking a friend to her Uber and waiting until she’s out of sight or waving to my boyfriend from our stoop as he drives off to the airport. Even if my guests don’t realize I’m doing it, taking the time to say bye in this way takes the sting out of farewells and often ensures everyone goes home laughing.

I didn’t fully appreciate the beauty of this tradition until my great-grandpa passed away at the age of 99. We visited his house one last time, and when we pulled away from the now empty driveway, I understood what a difference it made to have him waving his small hand until we couldn’t see him any more. It was a sacrifice beyond the physical strain of walking down and up his steep driveway. By waving until we were gone, he gave us the parting gift of being the one to turn away from an empty road so we wouldn’t have to.

While bittersweet, my last memory of him is ultimately a happy one because it’s no different than the many other times we said goodbye. Thanks to this cherished tradition, parting will always be more sweet than sorrowful.