Before Janja Garnbret, Martina Čufar Potard Ruled The Comp World

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

Climbing

At this time last summer, Martina Cufar Potard was settling in to watch the most historic rounds of competition climbing ever--the sport's highly touted debut in the Olympics--on the screen of a smartphone while lounging on a beach in France. Cufar Potard was once part of the international competition climbing circuit; a crucial part, in fact, so she could relate to the stress and rigor that the Olympian climbers would have to endure through the unique "Combined" format, the successive joining of speed climbing, bouldering, and lead climbing. Still, there was some cognitive separation, as Cufar Potard admittedly could never relate to the Olympic glitz or the sport's contemporary style that borrows from parkour. "The climbing style has changed completely," she says now when comparing the current era of competition climbing, the Olympic Era, to the era of her prime more than two decades ago. "The routesetting has changed a lot, and there are a lot of volumes that the competitors can hold onto. But it's much better like this. I don't know if it's better for all climbers, but it's better for those of us who watch it on a screen, for sure."

So, on a thin strip of sand in France, shaded under a parasol for the ensuing several hours, Cufar Potard assumed the universal role of an engaged Olympic fan. She steadily focused her attention on one Olympian, in particular: Slovenia's Janja Garnbret, whom many people consider to be the "Greatest Competitive Climber of All Time."

Cufar Potard "nervously" watched as Garnbret rallied from early slips in the speed climbing portion to utter dominance in the bouldering portion. And whenever the Olympic action on the smartphone got especially intense, such as when Garnbret edged out Team USA's Brooke Raboutou in a back-and-forth Speed heat separated by just 0.1 seconds, Cufar Potard calmed the nerves with a dip in the ocean. Her children too, Paco, age six at the time, and Tommy, age nine, watched Garnbret's Olympic masterclass on the screen of the smartphone and ultimately cheered when the final round culminated with Garnbret winning Olympic gold. "Just seeing her face that day, we could see that she was enjoying herself," Cufar Potard now recalls.

But there was more to the story than Cufar Potard and her children being passive, albeit anxious and invested, viewers on a French beach as Garnbret put on an Olympic masterclass. Like Garnbret, Cufar Potard hails from Slovenia. Moreover, the path that Garnbret ultimately followed to reach that culminating Olympic reward--a grind of national competitions around Slovenia and World Cup medals over the course of several years--was a trail that had first been blazed by Cufar Potard. Decades before the Olympics, when the sport of competition climbing was still in its grassroots infancy, Cufar Potard single-handedly created an archetype that Garnbret would eventually come to embody--the local hero of the Slovenian climbing scene, parlaying talent and unrivaled grit to global stardom and supremacy.

Cufar Potard herself is reluctant to admit such correlation, as she humbly states that she cannot take any credit for Janja Garnbret's Olympic gold. After all, Garnbret was only seven years old when Cufar Potard retired from the competition climbing circuit. Still, there is undeniable lineage, and pundits and analysts could do worse than postulate that Janja Garnbret would never have secured an Olympic medal, or risen to prominence at all, if Cufar Potard had not first pioneered the way. "It's true, I was the first one of the Slovenians to stand on the international podium," Cufar Potard says, allowing facts and candor to briefly eclipse the modesty. "That seems to always be an inspiration and a motivation to other climbers."

Homegrown talent

How, exactly, Cufar Potard pioneered the way is another matter. While Janja Garnbret was able to begin a quest toward greatness at a time when climbing's World Cup circuit was fully formed and widely celebrated, Cufar Potard first encountered competition climbing when the sport was in an infantile stage. As far back as the mid-1980s, Slovenia, which remained part of Yugoslavia until 1991, did have some climbing competitions, a few of which were nationally televised; but there was yet to be a World Cup circuit of any sort for the sport of climbing, so nascent competitive climbing contests for the best Slovenians were mostly local affairs in the 1980s. Even one of Slovenia's largest early climbing competitions, on an outdoor cliff in the village of Osp, in 1988, predated the World Cup circuit by a full year.

The international circuit of competitions was slow to form, and so too was Cufar Potard's development as a young climber. Originally from Mojstrana, at the foothills of Slovenia's tallest mountain, Triglav, Cufar Potard had childhood dreams of mountaineering greatness spurred on by her mountaineering father. At the age of nine, with her father, she successfully climbed Triglav. Yet, the active interest in climbing flared more when Cufar Potard was in the neighboring country of Austria, at a mountain camp known as Alpe-Adria Alpine. The grounds of the camp featured an artificial climbing wall near the sleeping inn, so evenings turned into makeshift climbing sessions.

Upon returning home to Slovenia shortly thereafter, young Cufar Potard was fanatical: "The only thing I wanted to do was climb," she recalls. Soon she and her father sought out another artificial climbing wall--this time only six miles from their home--and spent virtually every evening for the next couple of years climbing. A solid routine soon developed, splitting time between the artificial climbing wall and outdoor crags around Slovenia.

Cufar Potard's raw talent was evident, but it needed a showcase to flourish. This occurred in late 1990, when Slovenian organizers decided that the last climbing competition of Slovenia's National Senior Cup would feature an additional competition for kids. Cufar Potard, still a child, took part and not only won the girls' division, but earned a spot on the podium for the boy's division as well. She would later recall this as a pivotal moment, proving not only that she was irrefutably one of the country's best young climbers, but that she could break down barriers with her success. "Who could imagine a better start?" she says, as the great result motivated her to continue training with her father, and eventually aim to take part in the World Cup scene, by this time well-established under the guise of a governing body, the International Climbing and Mountaineering Federation (UIAA).

Strength in numbers

Such substantial national promise at the youth level did not immediately equate to international success. Cufar Potard trained mostly alone at home, hanging from fingerboards before school every morning and doing circuits--"like a hamster"--in the evenings on a climbing wall that her father had built. Plastered around her bedroom were posters of climbing's elite, those competitors she idolized and against whom she would soon compete--Robyn Erbesfield of the United States and Isabelle Patissier of France. Yet, when Cufar Potard turned 16 and finally got a chance to test herself against her global heroes, at a World Cup in Frankfurt, Germany, it was as inglorious as the home training. "I was really excited to be there, and to see the other climbers, and I remember how serious they all were in the isolation zone," Cufar Potard recalls. "And, of course, I remember my climbing--I didn't get very far on the route because I hit my elbow with my knee in the first roof section."

The botch, prompted by nerves, resulted in a 49th place finish for Cufar Potard at that World Cup in 1993; Erbesfield and Patissier placed second and third, respectively. A Swiss star in the midst of a banner season, Susi Good, placed first--and was on her way to also winning that year's World Championship gold medal.

But there were other noteworthy forces at play. Just a year before, in 1992, Slovenia won its first Olympic medals as an independent nation. Not only did this begin a long prelude to Janja Garnbret's eventual Olympic gold medal for Slovenia, 29 years later at the Tokyo Olympics; it stirred a sense of athletics-inspired nationalism among the country's population. At the Winter Olympics in 1994, two medalists in skiing actually hailed from the same hometown as Cufar Potard; one of which was a classmate, the other was the son of one of Cufar Potard's schoolteachers.

Cufar Potard herself made great athletic strides too. One year after the elbow-knee mishap at the World Cup in Frankfurt, she returned to the World Cup circuit and advanced to the final round for the first time at a competition in Birmingham, England. Even better, when results were tallied at the end of the 1994 season, Cufar Potard nudged into a highly coveted Top 10 spot. This, and her ability to become statistically one of the best climbers in the world with only the coaching from her father, caught the attention of the country's climbing nonpareil: Tomo Cesen, a Slovenian mountaineer most famous for several expeditions in the Himalayas. Recognizing her talent and potential, he offered to train her and soon became her official coach. Two other Slovenian climbers, Katarina Stremfelj and Maja Sustar, frequently joined the more structured training sessions that usually took place at a much larger climbing wall at Cesen's home.

These group training sessions resulted in Slovenia's national competition climbing squad beginning to take shape. "We were a great team," Cufar Potard says, reflecting on the way Cesen added knowledge to the great abundance of climbing that had been her training methodology up to that point. "[Cesen] first told me that rest is a very important part of the training. My performance got quickly better."

Competition supremacy

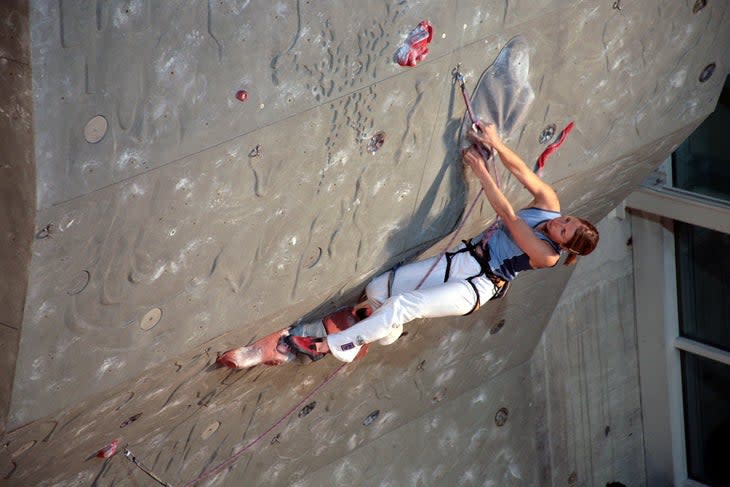

Cufar Potard continued to rise up the international ranks for the next few seasons. By the end of the 1990s, she was making appearances on World Cup medal podiums--the mark of truly being in the highest echelon of the sport--and beating many of her idols in the process. But her most incredible performance came in 2001, at the finals of that year's World Championships in Winterthur, Switzerland. Cufar Potard was the first of the 10 finalists to climb at the championship, which she cites as a fortunate position: "I was the first to go, so I didn't have a lot of pressure."

Instead of internalizing the beta of the World Championships' final route as most competitors do, taxingly attempting to memorize every last detail of the requisite moves, Cufar Potard purposely zoned out. She instead envisioned herself climbing faraway, on a route called It's So Easy at her favorite local crag back in Slovenia. Ultimately, the nostalgic and meditative tactic worked. "I climbed relaxed," Cufar Potard remembers. She did not successfully reach the top of the World Championships' final route, but she made it higher than the other nine finalists. The rousing performance earned her a World Championship gold medal--the first for Slovenia--and established a template that multi-time World Champion Janja Garnbret would later follow. "I didn't realize how important the victory was," Cufar Potard says of becoming World Champion. "It's only with the years that passed that it got more importance--being a World Champion is not the same as winning a World Cup." In other words, to Cufar Potard and many other competitors, a World Championship title is a greater accomplishment.

Yet, if any pundits dare to disagree, Cufar Potard stacked up multiple World Cup wins in 2001 as well: She won an event in Kranj, in her home country of Slovenia, and an event in Chamonix, France. She also won the Rock Master competition in Arco, Italy, that year--one of the most historic and prestigious competitions in all of climbing. She carried that good fortune into the following season, winning a World Cup in Yekaterinburg, Russia. Along the way, she carved out a comfortable existence through stipends from sponsors such as Adidas Five Ten, Beal, and Petzl--yet another template that Janja Garnbret would use decades later in arranging her own deals with Adidas Five Ten, Red Bull, C.A.M.P., and other brands.

Cufar Potard stayed near the top of the international heap even after those banner years, and continued to compete regularly on the World Cup circuit until 2006. Her final international competition was a one-off at the Military World Games in Italy in 2010--where, still in elite shape, she earned a silver medal. And as her own competitive career wound down, Cufar Potard started sensing the hype for a youthful Slovenian phenom from Slovenj Gradec named Janja Garnbret. "The first I heard talk about [Garnbret] was from [Slovenian national coach] Gorazd Hren," Cufar Potard recollects. "[Hren] was telling me that he had an extraordinary climber in his group. Then I heard she won all the youth competitions."

This coincided with other rumblings and rumors that Cufar Potard was hearing at the time, about sport climbing someday possibly being in the Olympics. To climbers like Cufar Potard, climbing's Olympic inclusion already felt overdue, even though it would take a decade for it to materialize. "It’s a bit strange that one of the primary, basic human movements--climbing--would take so long to get the approval from the International Olympic Committee [IOC]," she says now.

Generational inspiration

As for Cufar Potard's own Olympic dreams, the timing of her career never made participating in the Olympics a realistic possibility. By the time the IOC began working in earnest to actually adopt climbing, and particularly when it made the official announcement of climbing's Olympic inclusion in 2016, Cufar Potard had retired from competition and moved to France.

That's not to say her decision to step away from the competition climbing circuit was an easy one. "It's hard to leave behind something that was guiding my life for 16 years," she explains. But she found herself increasingly drawn more to outdoor climbing on real rock. "The fact was...I was not so motivated anymore," she says of her competitive drive right around the time climbing's debut at the Olympics was beginning to take shape.

Cufar Potard chose to pursue big climbing projects outside of the competitive context, most notably with an ascent of El Capitan in Yosemite during which she met her future husband, Nico. She and Nico settled comfortably into family life, and Cufar Potard was able to witness other Slovenian competitors follow in her footsteps. Two climbers in particular, Mina Markovic and Maja Vidmar, notched a number of World Cup medals for Slovenia and allowed the country's climbing infrastructure to thrive following Cufar Potard's retirement from international competition. This generated the perfect system for the youthful phenom Janja Garnbret to evolve into an eventual legend on the adult circuit and, in due course, give that Olympic gold medal performance that Cufar Potard watched beneath the parasol on a sunny summer day at the beach.

Garnbret continues to march closer to universal GOAT status with each successive competition victory, most recently with a win in the Lead discipline at a World Cup in Briancon. Garnbret is often framed as competition climbing's biggest "superstar," and she is one of the main protagonists in the recent documentary The Wall: Climb for Gold. Still, the fame is justified, as no other competitor in the men's or women's division has amassed such a diverse assortment of World Cup gold medals (in the Lead and Boulder disciplines) and World Championship gold medals (in the Lead and Boulder and Combined disciplines) with an Olympic gold medal as the accouterment. "I always knew [Garnbret] was an extraterrestrial," Cufar Potard jokes. The bountifulness of accolades makes Garnbret a marquee name in the qualification pathway for the forthcoming 2024 Olympics in Paris. And if Garnbret is in another Olympics, Cufar Potard plans to watch.

But more than an anecdote to Janja Garnbret's iconic story, Cufar Potard is a star whose accolades from a bygone period in climbing's storied history can stand alone--especially as fans and pundits clamor to uncover the secrets and the substrata of Garnbret's success. "Martina Cufar and, of course, her coach at that time, Tomo Cesen, somehow opened the door to our success," says Gorazd Hren, currently the coach of a far more sizable Slovenian national team, sometimes having up to 10 national-representative athletes in a given season. "With all [Cufar Potard's] great achievements, especially becoming World Champion back in 2001--and becoming European Champion the next year--Slovenians saw that despite our small country and small population, it is all possible with hard work and determination. Since then, we've continued her legacy and it became our tradition, or even obligation, to be one of the best countries in sport climbing."

These days, at 45 years old, Cufar Potard still climbs at a high level--outdoors, almost exclusively, with one of her more recent big sends being Grand Grand Bo, a 8b/8b+ (5.13d/5.14a), in France. She still maintains a sponsorship deal with Adidas Five Ten, and points out that new projects are often informed by her pioneering years on the World Cup circuit. "Competitions taught me a lot about myself, how to cope with the pressure," she reflects. "I was always very organized, which helped me a lot. If you know you trained well--and that you did everything you could do--then you get self-confidence, and it’s easier to confront any stressful situation."

For exclusive access to all of our fitness, gear, adventure, and travel stories, plus discounts on trips, events, and gear, sign up for Outside+ today.]]>