Janelle Monáe Knows She Has Your Attention—Get Ready for What's Next

In 2018 it feels like the world is at last prepared for Janelle Monáe. Ten years ago her EP, Metropolis: The Chase Suite, arrived as if from another continent, even planet. The layered, literary R&B album referenced classic space operas like Star Trek and the works of David Bowie and Prince. It seemed to foretell a world where black girls could imagine themselves without limits. I first heard about Monáe around then, from a much cooler coworker. I remember listening to “Many Moons,” the single that merited her first Grammy nomination, as my colleague and I traded visions of black self-determination.

It was 2008, before the social media heyday, when mass portraits of black identities were still controlled by a narrow-minded media complex. But Monáe kept working her own grooves anyway. Next came The Arch-Android in 2010, which broke the Billboard top 20 with tracks so infectious even Michelle Obama put them on her workout playlist.

It didn’t occur to me then to wonder where in the world Monáe had come from. But as I reached out to interview her this fall, it all of a sudden seemed essential to know. Every superhero has an origin story.

This is hers: Monáe, 33, was born in Kansas City, Kansas, the product of a black working-class neighborhood called Quindaro. The area was a settlement for Native Americans and, during the Civil War, a haven for abolitionists and black people who escaped enslavement. Her grandmother still owns the house Monáe played in as a child. When she visits, the stories she was raised on flood back to her. Her grandparents, Monáe tells me, passed down the tales from their ancestors about watching slaves escape during Bleeding Kansas, a series of violent clashes in the lead-up to the Civil War. “You can still see some of the ruins there,” she says. “Just knowing that I come from a place where people were trying to be free and fighting for their survival, it makes me feel like I have a lot of people to make proud. I don’t want their work and their blood and their sweat and their tears and their sacrifices to go in vain.”

It’s because of her parents (mother, a janitor; stepfather, a post office worker) that Monáe started to wear a black-and-white tux to public appearances, she says. The outfit was her uniform, an homage to the uniforms that blue-collar workers have worn for decades.

“I’ve always taken issue with people trying to place an image on what a young girl could be,” says Monáe. “I was going to decide that for myself.”

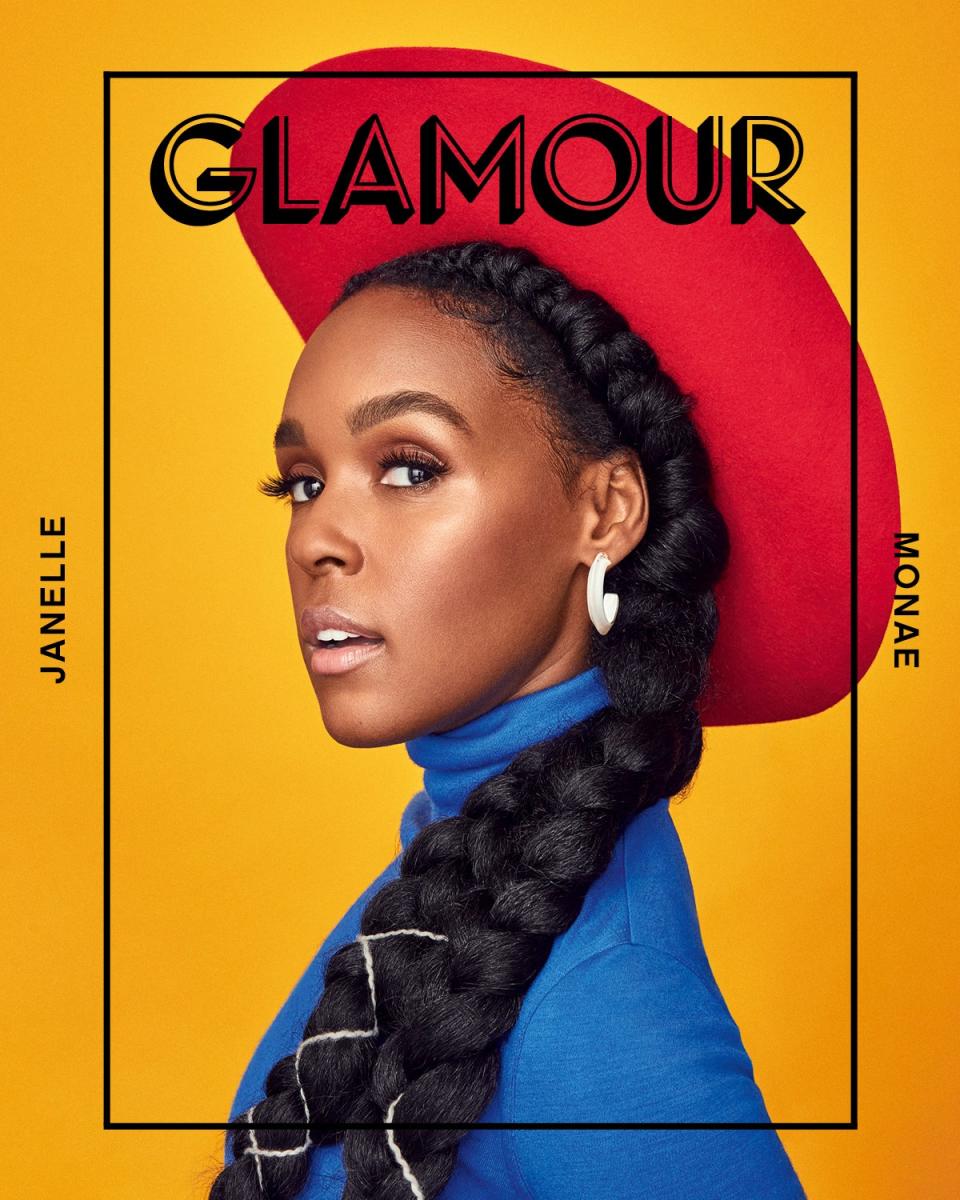

MM6 Maison Margiela coat. Jil Sander top, bustier, $530, skirt, leggings. Alison Lou hoops, $125. Clyde hat, $364. Kenneth Cole mules, $170.

When Monáe released Dirty Computer in April 2018, she seemed to want to break out of even her self-imposed strictures. Her latest work is a new beginning, showing us the fullest vision of Monáe to date. She describes the single “Pynk” as “a brash celebration of creation, self-love, sexuality, and pussy power.” And in its music video Monáe flaunts pubic hair and showcases a parade of voluminous pants shaped like vaginas. “I knew that I wanted to embrace all of me,” she says. “The good, the bad, the complicated, the humble, the cocky, the many dimensions of who I was.” In December, audiences will see her in Welcome to Marwen, her first feature role since Hidden Figures in 2016. The movie is as distinctive as its leads—a combination live-action and animated film about an artist named Mark Hogancamp (Steve Carrell) who tries to recover from a brutal attack by creating a miniature World War II town. Monáe stars as his physical therapist and friend. In other words, the healer.

“I’ve always taken issue with people trying to place an image on what a young girl could be. Early on I told my parents that I was going to decide that for myself.”

Monáe was raised in the Baptist church, a place that both fostered her love of music and emphasized, in her view, that she was different from some of her fellow worshippers. “I grew up with 12 aunts that I was very close to and that loved and cared about me,” she remembers. But with their affection came a host of opinions that they didn’t hesitate to make known. “They would say, ‘Oh, no skirts above the knees,’ or, ‘You can’t wear pants,’” Monae recalls. “I would…come in and just want to express myself. You had to deal with the looks and the community saying, ‘When you come in here, you need to look this way.’ I’ve always taken issue with people trying to place an image on what a young girl could be. Early on I told my parents that I was going to decide that for myself.”

The church may have sometimes stifled her, but it was also where Monáe learned the power of activism. She went door-to-door to feed the poor. She walked around the most dangerous parts of her neighborhood, “praying with people that people [would] put down their guns.” It felt good, she says, like, “This is what I’m supposed to be doing.” Monáe has carried that commitment to activism into adulthood. She has been an outspoken and frequent supporter of the Women’s March. At the 2018 Grammys she gave one of the most powerful speeches about Time’s Up; it was an extension of her own work with Fem the Future, which she launched in 2016 to empower female music executives, filmmakers, and sound engineers. The organization is her response to her own frustrations about opportunities for women in the business. That zeal for justice will continue to permeate her artistic work; her videos in particular create worlds of both oppression and rebellion. These fictional worlds, she says, “allow us to see where we could be headed. If we don’t right our wrongs, this could be our future.”

At this moment, even as the country seems bitterly polarized, she’s focused on a path forward. “We are going to have to figure out how to protect each other better than we have been,” she says. “We have to prioritize that, do a better job of looking after each other. I think we get an F in that. We’re going to have to stop getting lost in our own individualism because we are a [community]. We literally rely on each other to survive.”

“We are going to have to figure out how to protect each other better than we have been,” Monáe says. “We have to do a better job of looking after each other.”

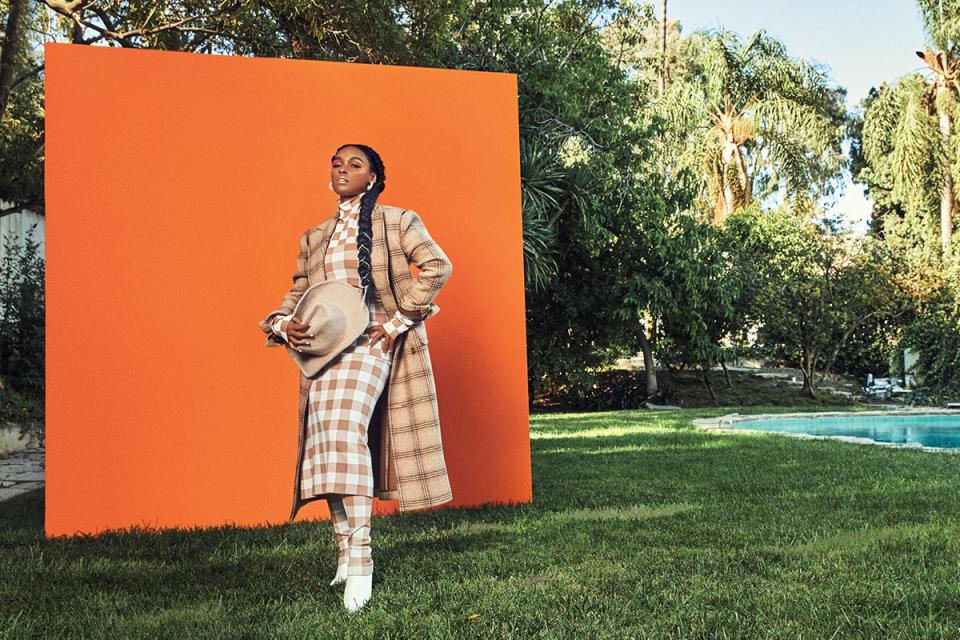

Helmut Lang coat. Celine top. See by Chloé pants, $345. Stetson hat, $115. Alison Lou hoops, $125. Louise Olsen silver rings, $220, $230. JaneD’Arensbourg ring, $132.

And how do we do that? For Monáe—an exceptional talent but one hell-bent on collective deliverance—the best chance we have at freedom comes to us as it did to her as a child: through stories. “Having real vulnerable moments allows us to see each other in each other,” she says. “Once we can reach a level of empathy, maybe we can like each other more. Maybe we can love each other more.”

It’s a kindness Monáe has tried to extend inward over the past year in particular. Her various identities have rallied her: “I’m a part of the LGBTQIA community. I’m a black woman. My parents are working class,” she says. None of us, she adds, has “our shit together,” so why not just own it, whatever we are?

“We can pull down the fake wallpaper, break the mirror that has been lying to us and making [us] believe that we need to be perfect,” she says. “We don’t need to be perfect to be respected.”

Kaitlyn Greenidge is the author of We Love You, Charlie Freeman.