Jan. 6 Was 'Far From Anything Resembling an Insurrection,' Says Trump's Then-Secretary of Defense

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

"Hearst Magazines and Yahoo may earn commission or revenue on some items through these links."

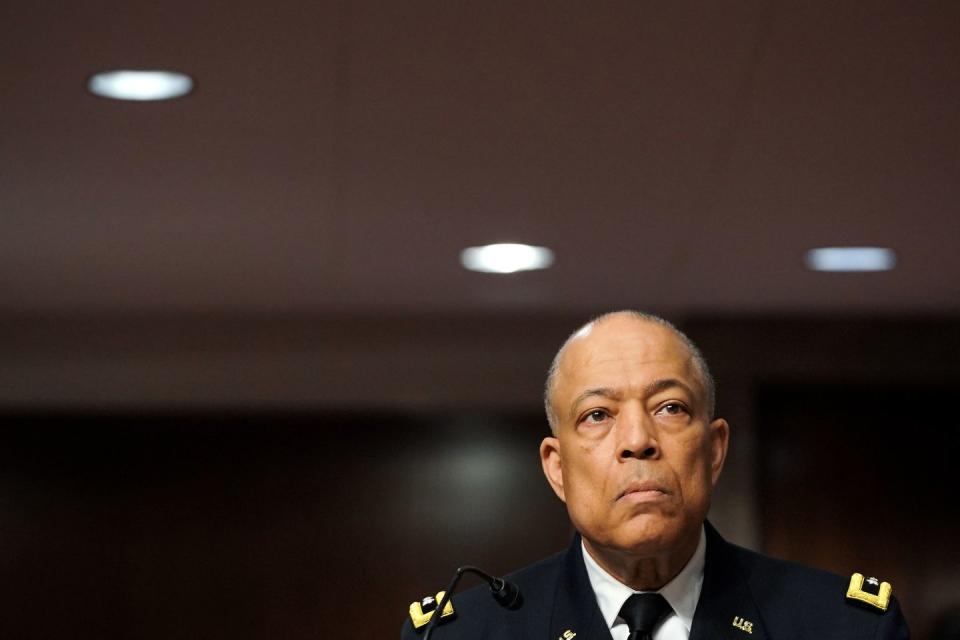

Former President Trump’s final (acting) Secretary of Defense Christopher Miller opens his new book with a scene from January 6, 2021. “At 3:44 p.m.,” he writes, “I was sitting at my desk in the Pentagon holding a phone six inches away from my ear, trying my best to make sense of the incoherent shrieking blasting out of the receiver. House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was on the line, and she was in a state of total nuclear meltdown.” He adds that Senate leaders Mitch McConnell and Chuck Schumer also “took turns hyperventilating into the phone.” Miller attributes the histrionics to the advanced age of these congressional leaders, and while our gerontocracy is a problem, it seems fair to assume even the most youthful majority leaders and minority whips might have verged on hysteria as they watched—and heard—a mob ransack the United States Capitol.

Regardless, Miller writes he told Pelosi and Co. that “I had already ordered the complete mobilization of the District of Columbia National Guard and that forces were on their way to the Capitol as soon as they were properly equipped and synchronized with the Capitol Police.” Except the first guardsmen did not arrive until 5:40 p.m., after the wave of violence had mostly receded.

The timeline of the Department of Defense’s response to January 6 isn’t a major feature of Soldier Secretary: Warnings from the Battlefield & the Pentagon About America's Most Dangerous Enemies, but it figured prominently in the questions I asked Miller when we spoke on Friday. We got into his experiences as a Green Beret and as a member of an even more secretive special operations branch, as well as his time on the Trump National Security Council and his brief stint in the Pentagon. More on all that here. But you don’t often get to talk to anyone who was privy to the Executive Branch’s activities on that day. One thing that came into focus while speaking to people for this story is that, for all the public fixation on the Department of Defense—just send in the National Guard!—there were thousands and thousands of non-military law-enforcement personnel in the capital that day: Capitol Police, Metropolitan Police, FBI, DHS, and more. Unlike the military, those agencies are built to focus on domestic and local security threats, yet they were unprepared for this one. Outside of the Metropolitan P.D., they were slow to respond. And as we shall see, in the lead-up, almost no one wanted the National Guard involved.

Still, it’s worth looking at what happened at the Department of Defense that day. Parts of the timeline remain in dispute, though one thing is not: Donald Trump, the sitting president of the United States, did not call or otherwise contact anyone in the national security apparatus that afternoon as he watched the seat of the national legislature get sacked on live TV. No one has testified that he took any action to restore order for hours. Trump certainly didn’t speak to his acting secretary of defense on the day, though Miller says the president volunteered in a meeting on January 5 that they’d need 10,000 National Guardsmen to deal with the crowd that would assemble the following day. This prompts the question of why, if Trump was concerned about crowd control in the lead-up, he was suddenly so apathetic about it when things went to hell.

D.C.’s National Guard force answers to the president via his secretary of defense. The chain of command is: President > SecDef > Secretary of the Army > Commanding General of the D.C. National Guard. After the outcry over how federal forces responded to the capital’s George Floyd protests six months before, many senior figures at the Pentagon were reluctant to get the Guard involved on January 6. (10 former secretaries of defense also issued an op-ed on January 3 warning against involving the military in “election disputes.”) Capitol Police Chief Steven Sund has said he asked for the Guard to be on standby at the Capitol, but was rebuffed by his bosses, the sergeants at arms for the House and Senate. The mayor of D.C., Muriel Bowser, specifically requested that National Guardsmen be mobilized but unarmed. They’d be stationed at traffic stops and D.C. Metro stations while Capitol and Metropolitan police took the lead on security. The D.C. Guard also mobilized a smaller Quick Reaction Force that could be deployed quickly. None of this is really in dispute, though various officials have denied they were specifically concerned about the “optics” of getting uniformed troops involved. (There were also reportedly fears among some—including Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Mark Milley—that Trump would attempt to use street chaos to invoke the Insurrection Act. Miller says he never shared this fear.) What’s in dispute is what happened on the day.

By 2 p.m., both Mayor Bowser and Capitol Police Chief Sund had requested the D.C. National Guard deploy to the Capitol. Sund was pleading for all available forces. Miller writes in Soldier Secretary that at 2:30, Army Secretary Ryan McCarthy “told me that they were working through several requests for National Guard support.”

Around 2:44, after reports that shots were fired inside the Capitol, Miller writes he saw the situation even more clearly: “The Capitol has fallen. We own this now…Let’s get forces moving towards the Capitol.” Bowser’s request came through and he “determined it was now a DoD mission” and “ordered the complete mobilization of the D.C. National Guard and movement to the Capitol of all available forces immediately. The order was issued at 3:04 p.m. We were taking over.” When we spoke, I asked Miller if these were the exact words he said to Army Secretary McCarthy, who was next in the chain of command.

“Yeah. McCarthy and—well, I don’t know if it was McCarthy. There’s still unexplained gaps in Army response. I don’t know what they are,” Miller says. “I don’t think the 1/6 Committee did—if you read the final report, it’s still a little fuzzy. There’s still a lot of controversy about who said what to whom. Someone supporting the Army made an effort—in one of the first brushes with getting the historical record straight—to characterize me as disconnected, not knowing what was going on, kind of a neophyte. At 3:04, the order went out for full mobilization. So I just kinda wanted to beat down that narrative that somehow the Department of Defense—that I—had slow-rolled the response. There were some communication problems—I don’t know what those were.”

The main one, based on public testimony, is that Army Secretary McCarthy took Miller’s directive to mean that the National Guard should be mobilized, but that they did not yet have his authorization to deploy to the Capitol. McCarthy has testified he believed he had to go back to Miller with a plan of action before the Guard could be deployed. (The Guard term is “employed,” but “de-” communicates things a bit better.) Miller says he takes responsibility for this miscommunication—that it could have happened—though he also writes that McCarthy and Joint Chiefs chairman Milley lost their composure on the day. (As tends to happen with these books, the author is always portrayed as the calm and rational one in the room. McCarthy and Milley declined to comment for this article.) McCarthy testified that he got approval from Miller to deploy the Guard around 4:30, which he’s said he told another general to convey to the commander of the D.C. National Guard, Major General William J. Walker.

Walker and a top lawyer for the D.C. Guard who was with him that day have denied the 4:30 call happened. In the Guard leaders’ telling, they first received approval to deploy to the Capitol at 5:08 p.m.—and not from McCarthy. But there seems to be little dispute that in the intervening time, McCarthy and others at the Pentagon were working on a plan of action. Walker has testified he could have sent 150 Guardsmen to the Capitol hours earlier.

For Miller, the Pentagon’s delay should have been immaterial. “Hey, man, at the end of the day, a two-star general gets paid to make decisions,” Miller told me of Walker. “Maybe he was trained and educated and had different experiences than I did. But no one has really dug into the fact that we had a two-star general with all the authority he needed to employ his forces as he saw fit. People will claim like, ‘No, you restricted him with the memo.’ The memo has the ‘get out of jail free’ card that all memos and all guidance always have to military forces, which is essentially, if you see something on the ground that negates all of this, just go do what you think is right. He had the authority to do that…Walker’s making it sound like he had his hands tied. That's not the way the military works.”

“The memo” here refers to a January 4th document signed by Miller and addressed to McCarthy that essentially denies the Guard the authority to get involved in any capacity on January 5-6 without Miller’s express permission. What Miller considers the “‘get out of jail free’ card” comes at the bottom: “At all times, the DCNG will remain under the operational and administrative command and control of the Commanding General,” it reads, meaning Walker, adding in a subsequent paragraph: “You may employ the DCNG Quick Reaction Force (QRF) only as a last resort and in response to a request from an appropriate civil authority.”

Essentially, Miller argues that Walker should have sent in the QRF on his own authority when he didn’t hear from McCarthy. D.C. Guard leaders could have read that last paragraph as directed at McCarthy, however, and they’ve alleged he was “incommunicado or unreachable for most of the afternoon.” (There’s also some dispute about how ready the personnel in the QRF were for riot control. Their mission was to quickly react to incidents at traffic checkpoints and Metro stations, not to a large-scale public disturbance on Capitol grounds.) Walker, Capitol Police Chief Sund, and the D.C. mayor’s chief of staff tried to call McCarthy around 2:30 p.m., but reached two of his subordinates at the Pentagon instead. The other participants have said one of them, Lt. Gen. Walter Piatt, voiced concerns about the “optics” of getting the Guard involved. Piatt denied that but subsequently softened that denial. The Army omitted from its initial timeline that the other official, Lt. Gen. Charles Flynn, was on the call, possibly because it feared associations with his brother, Michael. An internal D.C. Guard timeline suggests that both Piatt and Flynn “recommended for D.C. Guard to standby and start drafting a plan for courses of action.” But the more pressing question is why McCarthy himself was not on the call. Neither Piatt nor Flynn were in the chain of command.

Miller wondered to me if Walker was getting bad advice on the day, and also why he was subsequently appointed sergeant at arms for the House of Representatives. But there’s also the question of what Miller was thinking as the Guard failed to materialize in the minutes and hours after he ordered them to deploy at 3:04. “That started the process, and I thought that QRF would roll,” he says. “But I also knew that there's a lot of stuff that has to happen. That’s part of the purpose of this damn book, to bridge the gap between the American public—which has ideas about how its military works—and how it actually works. It’s not a video game. It’s not Halo, it’s not Call of Duty. You gotta get troops ready, you gotta get them re-equipped, you gotta go over rules of engagement, you have to do linkups, all this stuff.” Broadly, senior leadership at the Pentagon did not feel they could just send the Guard in, even if the Guard had deployed the previous summer to perform crowd control on the streets with law enforcement. It wasn’t just a question of “optics”: done badly, adding troops to the mix could have made the situation worse.

“At the end of the day, it was a pretty typical—actually, it went a lot quicker than I expected,” Miller says. “They could have probably gone earlier, but at the end of the day, I'm really, really glad that—Our armed forces should only be used for domestic law enforcement as a last resort.”

Miller is clearly fed up with what he feels is Monday morning quarterbacking. He feels that the lesson learned from Vietnam was that senior brass should not micromanage commanders on the ground. “Train your people and trust them and give them mission type orders and let them execute the way they see fit,” he says. Micromanaging “would run counter to everything I stood for in the way I did things. When times are tough, it’s easy to change your philosophy, but then you’re bankrupt, and you lose the respect of all your people. I knew it was chaotic, I knew things were difficult. Hell, I was in the D.C. National Guard. I know how doing crowd control and riot control and transitioning to police functions is. I’ve served and seen how getting re-missioned quickly takes a bit of time.” He added that even if the Guard had just run this type of mission six months before, they’d have new people and would still need a briefing.

One open question is how much intelligence the security apparatus had in the lead-up. In the book, Miller describes “a rowdy band of MAGA supporters, infiltrated by a handful of provocateurs, who were traipsing through the halls of the Capitol, taking selfies, and generally making a mockery of the entire institution.” A footnote on “provocateurs” links to a New York Post story citing one “law enforcement source” to suggest Antifa was involved, though Miller offered something else in our interview: “There were insurrectionists, and there were organized fighting forces,” he remembers telling a House committee in the aftermath. “The Three Percenters, the Proud Boys, all the people who have subsequently been indicted and many of them prosecuted and found guilty of sedition. Those were the ones we were watching.” He says this was based on pattern recognition: These groups had been out streetfighting regularly since the summer.

But the FBI must have had an eye on these same groups, and where were they that day? It was ultimately law enforcement who cleared the Capitol, including the FBI. Many journos like me have asked why the Guard wasn’t there earlier, but fewer have asked the same of law enforcement.

Miller is certainly clear on another thing: January 6 was not an insurrection. “Yes, the riot at the Capitol on January 6 was stupid and criminal and an absolute disgrace,” he writes in the book, “But it was far from anything resembling an ‘insurrection’ or, as the Democrat slogan repeated ad nauseam suggests, an ‘attack on our democracy.’” I asked why.

“Come on, America is way more resilient,” Miller says. “If we put ourselves in a position where a riot with insurrectionists interspersed in there can do one activity that can overthrow the government, that’s ludicrous, and it's just hyperpolitical and is not founded in reality or history. That however many people were up there—was it 2,500?—were somehow capable of overthrowing the republic is just, you know, it's just not based in reality in my mind.”

“So it's less about intention,” I asked, “than the fact that it was unlikely that they would succeed?”

“There was no way that a group, one small group like that, was going to overthrow the republic. Please. That's kind of where I'm just like, ‘Come on, take a deep breath.’ The country is not so fragile, and our form of government is not so fragile that one demonstrably horrible, stupid, and sick event would cause our republic to fall.”

Miller pointed to the idea that rioters getting hold of “the elector box” would have brought about the end of the republic, which is indeed silly. It’s less silly to consider what might have happened if they had gotten their hands on members of Congress, hysterical as they may have been while on the phone with the acting secretary of defense. Elsewhere in our conversation, Miller cited the grave nature of what the Army heading to the Capitol communicates—the Executive marching on the Legislative Branch—as another (understandable) reason that Pentagon officials were reluctant to get involved. But that is what Trump’s fans did: They marched on the legislature while it was in the process of confirming he would soon lose power over the Executive. Maybe it was never likely to work, but that doesn’t change the nature of the crime.

Also, they got pretty close. They had a lot of time.

You can find the rest of our discussion with former Acting Secretary of Defense Chris Miller here.

You Might Also Like