James May's Gin Is Drier (and Droller) Than His British Sense of Humor

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

- Oops!Something went wrong.Please try again later.

You probably know Brit James May as the consummate thinking-man’s car guy from Top Gear and Grand Tour. He’s a globetrotting gourmand with a gift for getting under the hood of anything he sets his sights on, and then bravely giving it a go himself. So, when the 60-year-old television star forayed into spirits by launching James Gin in 2021, he did it with his trademark broad curiosity, minute attention to detail, and self-deprecating humor.

It was new territory for May. For the past 20 years, he’s co-hosted the most popular car shows in history, alongside Jeremy Clarkson and Richard Hammond. Often the straight man of the trio, May is the charmingly heady faux-curmudgeon (or maybe not so faux, we wonder) who dreams of Sancerre on the Mongolian steppe, plays devil’s advocate in the studio, and somehow always ends up with the worst cars on the best road trips. But, if you’ve delved into May’s non-automotive shows like Oh, Cook!, Our Man In Japan, and Our Man In Italy, you know that he's more than just a car guy—and James Gin exemplifies that truth.

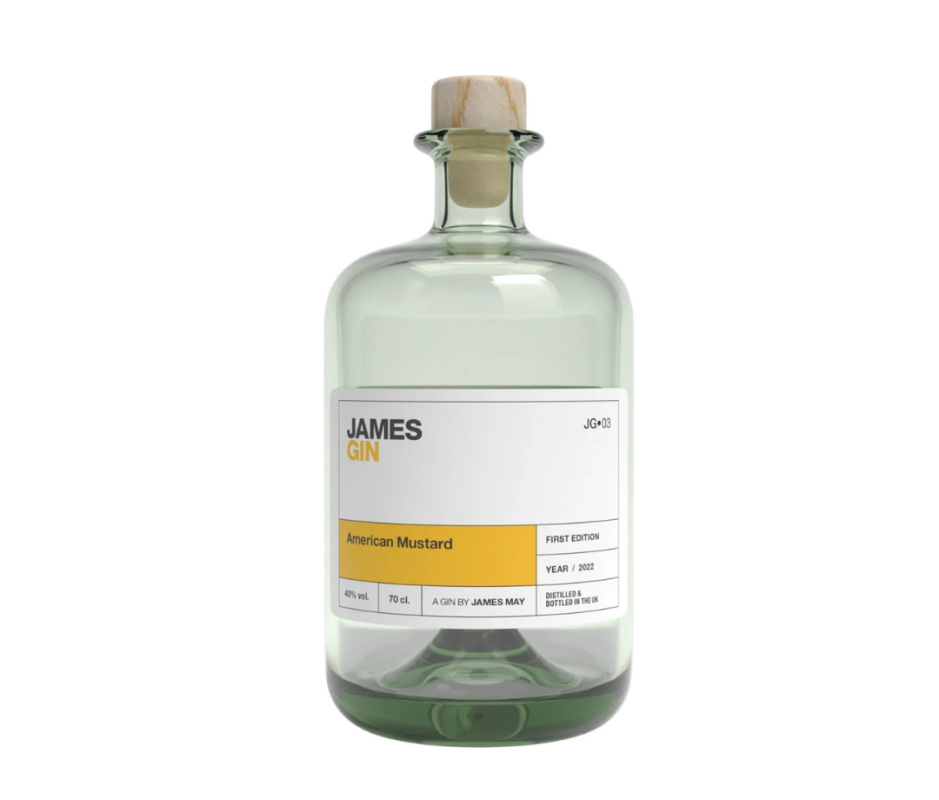

We’ve all heard of locally foraged gin, but what May has done so far with James Gin might be called emotionally local, nostalgically local, or reverie-to-glass. His love of Asian food, plus the cozy dampness of a cold winter day in a warm English cottage, inspired his Asian Parsnip gin. His American Mustard gin teases his love of American yellow mustard with a knowing wink, while his newly released London Drizzle evokes the smell of light rain on dry pavement with a genuine sincerity. On most weekends, May sips one of his gins with light tonic at The Royal Oak, a Wiltshire pub he bought at the beginning of the pandemic, where he’s the resident art curator and soft lighting stickler—and where even he pays for his own drinks.

May spoke with Men's Journal about the learning curve of running a new spirits brand and new pub at the same time, how he likes his gin-and-tonic, where he gets his left-field flavor inspirations, and how the man who's fixed vintage cars on the roadside of every continent still gets foiled by bottle corks.

Related: The 25 Best Craft Gins to Drink in 2023

Men’s Journal: How did James Gin first come to be?

James May: It was just a bit of fun. I was slightly between jobs, and the pandemic affected things. I was with Will Daws, who produces my television series, and he said, "Have you ever made a gin?" And actually, I had. I made it with [wine expert and TV host] Oz Clarke years ago when we did one of our drinks shows. So, I said, "Yes, I've always wanted to have a go with another one, and do something a bit more left field."

We got talking to another friend of ours, Gus Colquhoun, who's the business brains behind this, and he knew a distiller, Hugh Anderson, who happened to live near my little country cottage. So, we went to see Hugh, and I said I had this idea about a gin that is very British, quite dowdy, but also a bit Asian. I like Asian food and Indian food, which are massively popular in Britain. I came up with this idea, Asian Parsnip, and Hugh said it's worth making a thousand bottles. He's a craft distiller, so that's as much as he can make really. He said, ‘We’ll make it, it won't cost you that much, you all have to put a bit of money in.'

We summed up the money, made it, and put it online. I tweeted about it, and we sold it all within a few days, which was a bit of a surprise. People seemed to like it as well. So, we made another batch. And then another one. We've had to outsource the distilling to a bigger operation because it was too big for Hugh’s little place, although he still oversees it to make sure they get the recipe exactly right. Then we had a go at making new flavors like American Mustard and Navy Strength, and we've just invented another flavor, London Drizzle.

What inspired these flavors that no one has ever put in gin?

With American Mustard—I like French's mustard, which you get quite a lot there—the idea was that when we distill the essence of America, we arrived at burger mustard as the thing that makes America great. So, we turned that into a gin. But it works quite well because mustard is a nice ingredient to put into gin.

With London Drizzle, we tried to do the same thing. It's meant to be a bit self-deprecating. When you lift it to your nose, it should invoke the sense of walking out in London when it's been drizzling. It makes that petrichor smell that comes from rain hitting dead organic matter on the pavement. I've never met anybody who doesn't like that smell, and it's very subtle.

So, it's quite a difficult thing to reproduce exactly, but we've got something that will call it to mind. It's a nice flavor as well. These things only work if they're actually nice to drink. Everything else on top of that is just something to talk about—but it was quite difficult to do in a gin. Beetroot, weirdly, turned out to be one of the things that created it. And oyster shells, which we then ditched because the gin wouldn't be suitable for vegans.

Courtesy Image

I know from your recent vegan episode of Oh, Cook! that you’re mindful of that.

I haven't quite got the strength of character to be a vegan or even a proper vegetarian, although I don't eat that much meat these days. But I wonder if in 150 years' time, people will look back and think "Isn't it amazing they used to eat animals?" That's why we did the vegan episode of Oh Cook! It's quite an interesting challenge if you're an amateur cook, which I am, to try and make things that aren't trying to be pretend meat, but are nice and tasty in their own right.

In the West, we tend to think that vegetarianism is a radical idea. But if you go to, say, the southern half of India, it's not unusual at all. You go to a restaurant and say, "Well, actually, I'm vegetarian." They go, "Well, actually, so is this restaurant."

Any other eccentric flavors you’ve been cooking up?

We worked for a long time on trying to make a gin that smelled of petrol or gas. We called it Gasoline Dreams. But we've never managed to do it, because everything that makes the petrol smell is hideously toxic, and finding nice organic alternatives that still produce that same slightly putrefying smell of freshly pumped gas has so far eluded us. We'll have another go in the future.

How long have you been on the gin-making path?

I went to Plymouth Gin with Oz Clarke in 2009. We were allowed to muck around with the still in the lab and make a tiny sample of our own gin. I've thought about it on and off ever since. But you can't really have a still at home. You have to license it in the UK. Otherwise, you're basically a moonshiner.

I thought about that, and every now and then I'd pick up something or eat something and I'd think "I wonder if that would work as gin?" Then I had this idea of the parsnip, because it's a strangely British thing. We eat lots of parsnips at Christmas. We like parsnip soup and parsnips with our roasts. They somehow have a very English flavor. When I eat them, I think of damp air, damp earth, being cold in the house, and having to put the fire on.

But because we’re great enthusiasts of Asian food in England, especially Indian food and spicy things, we could counter that with a spiced sparkle. It took a bit of experimentation, but it worked. We only sell a tiny amount compared with the big gin makers, but it's well liked. Not many people dislike it, and some people absolutely rave about it.

How do you like to drink your gin?

I've recently been encouraged to have gin martinis, and the barman at my pub has started inventing cocktails. He's made a version of a Bloody Mary with the Asian Parsnip James Gin. He always says to me that you must remember when you come in the pub to order something a bit different—don't just have a pint or a gin-and-tonic. Though I do tend to have gin-and-tonics because I think it's such a happy drink. They work best with light tonics, low-cal ones.

I don't know if this is part of aging, but I’ve found in the last few years that regular sugary drinks like Coca Cola and Sprite taste too sugary. The first time you try the light versions like Coke Zero, you think, "Oh, it tastes a bit thin." It's a bit like giving up sugar in your tea or your cornflakes. Once you've done it, you can't actually go back, because everything else just feels disgustingly sticky.

I've found that if you put the Fever Tree light tonic with Asian Parsnip, you can actually taste the gin better. Otherwise, you can very easily end up with what is just a glass of tonic water that happens to light you up a bit. You're not actually enjoying the flavors of the drink.

What has been the biggest surprise so far about launching a gin brand?

Exporting it. It probably shouldn't be a surprise, but even exporting it to Europe now that we've had Brexit, there's a lot of paperwork, a lot of admin. Different places like it in different size bottles—that surprised me.

The biggest surprise, though, is that people took notice. Gin isn't particularly hard to make. Even if you haven't got the license, it's quite easy to chuck pretty much everything from wood chips to grass cuttings to bits of old fruits to nuts into a still and make gin. The gin boom had already peaked, and I just thought that it's a bit of fun even though people might not be interested. But people were interested.

It also surprised me that you could make a gin in very small volumes by the general standards of the drinks business—I mean microscopic—but there are people interested enough to buy it. We're talking about thousands of people, not hundreds of thousands or millions. But we sell as much gin as we make. We don't make any money because the profit goes back into making more gin. So, it's not a business venture in the true sense. Most businesses these days seem to be started to eventually be sold.

I'm not going to be pretentious and pretend it's a "calling" or a "labor of love." It's just good fun and a nice thing to have. It's lovely to be able to go to someone's house and say, "I brought you a bottle of my gin." It's a bit like a homemade jam, but it's gin. It feels a little bit more exotic somehow because there’s the question of, "How did you do that?" Well, I got a man to do it for me.

Related: The Best Places to Visit in England

As someone coming in from the outside, what’s your take on the spirits business?

The interesting thing about the spirits world, about which I knew nothing before—apart from obviously my enthusiasm for drinking them—is that people are very enthusiastic about it. You have to be really very interested in the stuff that people are making, even if you're distilling it on someone else's behalf or you're a big distributor.

You have to be enthusiastic. You can't turn up and simply flog wine to a pub. You have to be able to talk about it because your rival is a wine enthusiast, gin enthusiast, or whiskey expert. They will outdo you because enthusiasm counts in a business that's ultimately about pleasure and having a nice time. It's not quite the same as refrigerators or self-tapping screws.

What’s it like to be a new pub owner?

Again, because my business acumen is so poor, I bought the pub just as the pandemic kicked in. But I'd already agreed to buy it, so a deal's a deal. I only own half of it, I've got a partner in it, but it struggled for a long time. Recently, from the second month of this year onwards, it's become really popular. The word has gone around a bit. We've got the best chef in the area. It's a happy place, and people are starting to use it. There's even been a couple of days where we've had to turn people away, unfortunately, because we were full. Which is a great thing for us, though disappointing for them.

We can't expand it because it's an old pub. There's nowhere for it to grow. In fact, the carpark is too small for the pub. There's nothing we can do about that because we either expand into our own garden, or if you try and expand the other way we fall into a small river.

Courtesy Image

Small can be good. You probably don’t want to be as busy as Clarkson’s Farm.

I gather that annoys his neighbors quite a lot. We're not quite at that point. The immediate neighbors—there’s only a handful of houses—are all regulars at the pub anyway. So they're not going to moan.

How often do you go to the pub?

Pretty much every weekend. [Co-owner] Simon Andrews and I have a very strict rule: We don't do mates rates, freebies, or free rooms for people who claim they're an influencer on Instagram or anything like that. Everybody pays, including me. And they pay the full whack, because to be honest, the margins on something like a pub are so small that even though our turnover is healthy, no money comes back out of it. It all goes back in.

The building requires constant maintenance, the cost of ingredients has gone up, the cost of insurance has gone up, energy has quadrupled, so it's always a struggle. It's a bit of a British cliché and common fantasy: when you get older, you want to buy a pub. But people don't realize that they're almost impossible to make work as a business. They're very expensive, they're antisocial because you've got to be there all the time, they're extremely hard work, it's not very well paid, and if you're not careful, it can be very bad for your health because you eat too much food and get pissed all the time. It's not something to be taken lightly.

That's why Simon and I don't make any attempt to run the pub. We immediately employed a manager and let him do everything. We come up with suggestions for the menu or things to do with the décor and they completely ignore me. They go "Yes James,” and as soon as I’ve gone, they just forget about it. The only real difference I've managed to make is that I've been able to select the art that goes on the wall, because that's something I'm quite interested in. But they won’t even turn the lights down when I tell them to. I go around the bar and turn them down myself and then bam, they turn them back up again.

Some people underestimate the power of lighting in hospitality.

Absolutely spot on. That’s why it's a whole profession in itself in theater and filmmaking. It's a very powerful ingredient in setting the mood of the place. You've also got to be very careful anywhere that serves food, especially if you start introducing anything other than white light, because certain foods only reflect certain wavelengths of light. If you put the wrong color of light, for example, if you put red lights on your vegetables, they start to look black rather than green.

With the pub, the bar's usually quite nicely lit, then you go around the central fireplace and then there's the bit that we call the snug. It's not particularly snug-ish, but that's the sort of main eating bit. That's the bit that’s always too bright, and the previous owners who actually restored the pub put downlighters in the roof, and they're always up too high. It's a little bit like a Boeing Seven-Four-Seven coming in to land in the dining room. I go in and I just turn it down a bit. But I go in the next week and all the lights are up like they want to do an operation. It’s infuriating.

What are your hopes for the future of James Gin?

I would like it to be a bit bigger in America. Californians definitely like it. We’re pleased with that. If you're doing a thing like importing gin, you have to almost think of the U.S as individual states, rather than the United States. There's slightly different rules everywhere. We'd also like to get it into Europe more, but it's difficult and ends up being too expensive. A lot of nice Napa Valley wines never make it to England because they become unreasonably priced by the time they've been exported and taxes have been applied. So, you Americans keep them to yourselves, and I don't blame you one bit.

So, yes, I'd feel very gratified if it became a cultish drink. But I don't imagine that it's ever going to be really huge, or that there's going to be rows and rows of it on supermarket shelves. It's too expensive, for one thing. Even if we were making a million liters, it's always going to be a niche product. More people are buying it, the sales are increasing very slightly, and on the whole, people really like it and rate it very highly. It's not designed as a get-rich scheme or anything like that. I don't think it ever could be. There are a lot of people making gins in very small batches all over the British Isles. Thousands of them, probably.

Courtesy Image

How has your fame and notoriety played into the marketing of it?

I have a slight advantage because my name is known, and I can exploit that a bit. But I don't want to turn into a tart. Because people often approach me about other things and they say, "You've got a big Twitter following, could you do this for us? Could you do that?" And I say "No, I'm not going to do that because I'm not a marketing agency." It would piss off the vast majority of my followers if they thought I was just selling to them. They follow people on Twitter to get a bit of insight or the odd joke—that's all it is. I don't like it when it turns into aggressive subliminal marketing.

I do tweet about the gin, and we tend to be very self-deprecating about it. I boast that we're number 30,291 in groceries on Amazon, that sort of thing. That's the way I promote it. But I don't go on there and say "Buy my gin, it’s brilliant, and is much better than Ryan Reynolds’ gin," or anything like that. I rather like his gin, actually.

Packaging is its own industry with spirits. How did you decide on yours?

From the start, we went for that sort of slightly medicinal laboratory look for the bottle. Some people have complained, but we really liked the shape of the bottle. The hardest bit about presenting gin is getting the right corks.

Lately, for the Asian Parsnip, we've only been able to get slightly smaller corks, which have a smaller diameter than the top of the bottle. It doesn't affect its stopping ability, it’s just an aesthetic thing. So, we had to change the pictures on the website to show everybody what it really looks like. But then that changes the shrink wrapper that we put on, because it has to be a slightly different size to start with in order to shrink accurately round the cork. So that's actually the trickiest bit of the operation in many ways: the unpredictability of the next batch of corks.

Want me to send the corks back from the bottles I have?

Yeah, well… would you mind?

Men’s Journal aims to feature only the best products and services. If you buy something via one of our links, we may earn a commission.

James Gin Asian Parsnip

James Gin American Mustard

Courtesy Image

James Gin London Drizzle

Courtesy Image